|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020). Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020).

Check out my other conversations with ChatGPT

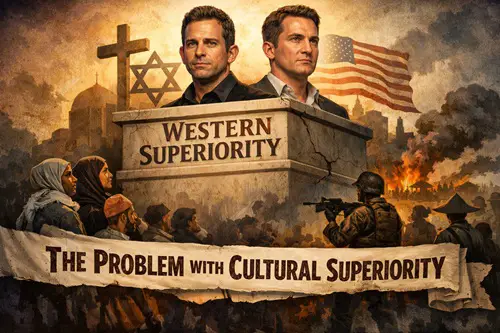

ON SAM HARRIS

Mysticism Without Metaphysics Harris vs. Wilber on Mysticism Harris and the Four Atheist Horsemen Harris on Islam and Hamas The Western Superiority Debate Spirituality for Atheists The Problem of Cultural SuperiorityIn the Thought of Harris and MurrayFrank Visser / ChatGPT

Sam Harris and Douglas Murray are often grouped within a discourse that frames Western civilization—particularly its Judeo-Christian heritage—as inherently superior to other cultures and religions. This position, whether explicit or implicit, has become a recurring motif in contemporary debates about secularism, Islam, and liberal values. While it is cloaked in the language of rationalism, human rights, and universalism, the underlying claim of Western superiority warrants critical examination. 1. The Intellectual FramingHarris, primarily known for his critique of religion, argues that certain religious systems—most notably Islam—pose disproportionate threats to global stability, human rights, and rational public discourse. Murray, in a similar vein, frames Western societies as havens of liberty, equality, and scientific rationality, in contrast to what he sees as the authoritarian tendencies of other cultures. Both rely on historical and contemporary examples of social progress—democracy, science, gender equality—to buttress their claims. On the surface, this argument appears empirical and value-neutral: it appeals to measurable outcomes. Yet closer inspection reveals that the argument often depends on a selective reading of history and culture. By highlighting Western achievements and contrasting them with the supposed deficiencies of non-Western societies, these thinkers implicitly endorse a hierarchy of civilizations. This echoes a longue durée of intellectual thought, from Enlightenment Eurocentrism to 19th- and 20th-century social Darwinism, albeit in a modern, secularized guise. 2. The Problem of Selectivity and ContextCritics argue that Harris and Murray's claims rest on an implicit double standard. Western societies are credited for their accomplishments while their failures—colonialism, slavery, systemic racism, and contemporary socio-economic inequalities—are often marginalized or rationalized as historical accidents. Conversely, non-Western societies are judged primarily by their perceived deficiencies, with little attention given to their achievements, resilience, or internal heterogeneity. Moreover, the attribution of moral and intellectual superiority to a religious or cultural heritage abstracts away the lived realities of its adherents. Western societies, while historically influenced by Judeo-Christian norms, are also deeply shaped by Greco-Roman rationalism, Enlightenment secularism, and centuries of intercultural exchange. To conflate "Western" with "Judeo-Christian" or to ascribe an inherent moral advantage risks oversimplifying complex social dynamics. 3. The Risk of Cultural EssentialismThis discourse tends toward cultural essentialism: the idea that civilizations possess stable, inherent qualities that define them as either superior or inferior. Such thinking can lead to two problematic consequences: Moral Certainty – By positing a civilizational hierarchy, Harris and Murray risk cultivating a sense of moral infallibility. This discourages self-critique within Western societies and glosses over internal contradictions. Othering – By framing certain religions or cultures as fundamentally incompatible with liberal values, this perspective may inadvertently fuel Islamophobia or anti-immigrant sentiment, even when presented in secular or intellectualized terms. 4. The Question of UniversalityBoth thinkers appeal to universal values—reason, human rights, gender equality—but their methodology often conflates universality with cultural specificity. Just because Western societies have institutionalized these values more effectively in recent centuries does not mean that they are the sole or natural custodians of them. Non-Western traditions—ranging from Confucian ethical frameworks to Islamic philosophical schools—have also cultivated notions of justice, moral responsibility, and intellectual inquiry. To ignore these contributions is to mistake historical contingency for ontological superiority. 5. A More Nuanced AlternativeA critical perspective would decouple cultural achievement from moral or intellectual essence. Societies can be evaluated empirically—on governance, human rights, scientific output—without asserting that one civilization is ontologically superior to others. This approach acknowledges both the achievements and the failings of any culture, and it resists the temptation to essentialize morality or rationality along civilizational lines. 6. Gaza and the Moral Framing of Asymmetrical WarThe war in Gaza has become a particularly revealing case study in how Harris and Murray frame civilizational conflict. Both tend to interpret the conflict through a lens of moral asymmetry: Israel is situated within the liberal-democratic West, while Hamas is portrayed as an explicitly theocratic, genocidal movement animated by Islamist ideology. From this perspective, the war is not merely territorial or geopolitical; it is civilizational. Harris, consistent with his long-standing critique of Islamism, emphasizes intent. He argues that groups like Hamas are morally worse because they explicitly aim at the destruction of Israel and celebrate martyrdom and civilian targeting. The asymmetry, in this framing, lies not primarily in casualty numbers but in declared goals and moral doctrines. Murray similarly underscores the ideological character of Hamas, presenting the conflict as a frontline battle in a broader struggle between liberal societies and religious extremism. Critically examined, however, this framing tends to compress a complex geopolitical conflict into a moral parable. By casting Gaza as a theater of civilizational self-defense, structural factors—occupation, settlement expansion, regional power dynamics, internal Palestinian politics, and humanitarian consequences—risk being backgrounded. Civilian suffering in Gaza is often acknowledged but subordinated to the overarching narrative of existential defense against barbarism. This mode of analysis also reinforces the broader superiority thesis. If Israel is framed as a proxy for �the West� and Hamas as a proxy for �Islam,� then the conflict becomes emblematic proof of the moral gulf between civilizations. Such framing can obscure the plurality within both Israeli and Palestinian societies and flatten internal dissent. It risks transforming a political conflict into a metaphysical one, where compromise appears as weakness and critique as betrayal. A more analytically rigorous approach would disentangle ideological extremism from civilizational identity and separate moral evaluation of tactics from broader judgments about cultural worth. Without that distinction, the Gaza war becomes not only a tragedy in its own right but also rhetorical ammunition in a larger narrative of Western exceptionalism. ConclusionWhile Harris and Murray often frame their arguments as rational and evidence-based, their claim of Western superiority relies on selective history, cultural essentialism, and an underestimation of the moral and intellectual capacities of other societies. Critically engaging with this position requires disentangling empirical observations from normative hierarchies and resisting the seductive narrative that one civilization holds a monopoly on reason, morality, or human progress. Ultimately, the defense of liberal values is strengthened—not weakened—when it is universalized rather than territorialized.

Comment Form is loading comments...

|