|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020). Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020).

Check out my other conversations with ChatGPT

ON SAM HARRIS

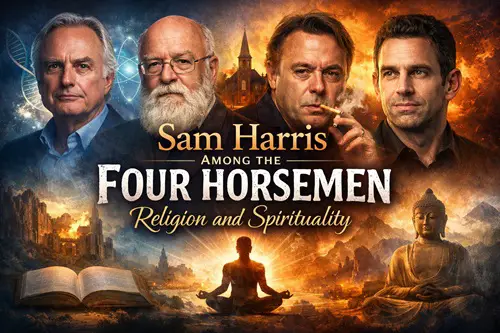

Mysticism Without Metaphysics Harris vs. Wilber on Mysticism Harris and the Four Atheist Horsemen Harris on Islam and Hamas The Western Superiority Debate Spirituality for Atheists Sam Harris Among the Four HorsemenOn Religion and SpiritualityFrank Visser / ChatGPT

Among the so-called “Four Horsemen” of New Atheism—Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, Christopher Hitchens, and Sam Harris—there is substantial overlap in their rejection of theism and revealed religion. All four argue that religious belief lacks adequate evidential support, that scriptural literalism is intellectually untenable, and that institutional religion often produces social harm. Yet when it comes to religion's phenomenological core—mystical experience, contemplative practice, and the concept of spirituality—Harris occupies a distinctive position. 1. Dawkins: Evolutionary Critic of God, Skeptic of MysticismRichard Dawkins approaches religion primarily as a biological and cultural phenomenon. In The God Delusion, he frames belief in God as a hypothesis about the universe—one that fails under scientific scrutiny. Religion is treated as an evolutionary byproduct (or “meme”), parasitic on cognitive mechanisms such as agency detection and pattern recognition. On spirituality, Dawkins is comparatively thin. He often acknowledges awe before nature—the “numinous” experience of evolutionary grandeur—but he is reluctant to preserve traditional spiritual vocabulary. For Dawkins, transcendence is poetic shorthand for scientifically informed wonder. Mystical experiences are reducible to brain states, interesting perhaps, but not epistemically revelatory. Harris departs from this stance. While he agrees that religious doctrines are false, he refuses to discard the contemplative traditions wholesale. He takes first-person experience seriously and argues that certain states of consciousness—non-dual awareness, self-transcendence—are empirically investigable and psychologically transformative. Where Dawkins sees religion as primarily a cognitive error, Harris sees it as a mixture of error and genuine introspective discovery. 2. Dennett: Religion as Natural PhenomenonDaniel Dennett, in Breaking the Spell, proposes studying religion as a natural phenomenon—subject to evolutionary, cognitive, and memetic analysis. He is less polemical than Dawkins or Hitchens and more interested in explanatory mechanisms. Religion persists because it exploits psychological vulnerabilities and social reinforcement systems. Dennett is cautious about spirituality. He does not deny that meditation or altered states may have psychological benefits, but he resists framing them in metaphysical language. For him, the intellectual task is demystification. Harris shares Dennett's naturalism but diverges in emphasis. Harris insists that subjective experience—especially the apparent dissolution of the ego—reveals something significant about the structure of consciousness. He draws explicitly on Dzogchen and Buddhist psychology, claiming that the “self” is an illusion discoverable through contemplative practice. Dennett, by contrast, famously described the self as a “center of narrative gravity”—a theoretical construct. Harris agrees that the self is constructed, but he maintains that its illusoriness can be directly perceived in experience, not merely inferred philosophically. Thus, Harris integrates phenomenology into atheism in a way Dennett largely avoids. 3. Hitchens: Moral and Political IndictmentChristopher Hitchens approached religion primarily as a moral and political problem. In God Is Not Great, he indicts religion for authoritarianism, anti-intellectualism, and cruelty. His rhetorical strategy is historical and ethical rather than neuroscientific or contemplative. Hitchens showed little interest in salvaging spirituality. He valued literature, art, and moral courage, but he did not explore meditation or non-dual awareness as replacements for religion. His humanism was secular, literary, and political. Harris differs markedly here. While equally critical of religious violence and dogmatism, he does not dismiss spiritual experience as mere superstition. He seeks to disentangle contemplative insight from metaphysical belief. In this sense, Harris is less purely secularist than Hitchens. He aims to retain the transformative aspirations of religion without its supernatural commitments. 4. Harris: Spirituality Without ReligionHarris's distinctive move is to argue that spirituality—understood as the systematic investigation of consciousness—can survive the death of theism. In The End of Faith and especially Waking Up, he contends that mystical experiences are real phenomena accessible through meditation, psychedelics, or disciplined introspection. These experiences allegedly reveal: • The absence of a stable, central self. • The non-duality of subject and object. • The possibility of profound well-being independent of belief. Crucially, Harris frames these claims within neuroscience and psychology. He treats contemplative traditions as proto-scientific disciplines of attention, whose metaphysical interpretations can be stripped away. This position sets him apart from the other three Horsemen, who generally regard spirituality as either aesthetic sentiment (Dawkins), an evolved cognitive artifact (Dennett), or a rhetorical distraction (Hitchens). 5. Tensions and CritiquesHarris's synthesis is not without tension. Critics argue that his “consciousness without self” risks reifying consciousness into a quasi-substantial entity—functionally similar to what religion once called soul or spirit. Others suggest that his appropriation of Buddhist terminology smuggles metaphysical assumptions under a neuroscientific veneer. Compared to Dawkins and Dennett, Harris places greater epistemic weight on first-person methods. Compared to Hitchens, he is more open to altered states as sources of insight. Yet he maintains alignment with all three in rejecting supernaturalism, scriptural authority, and divine command morality. 6. ConclusionThe Four Horsemen share a commitment to scientific naturalism and a critique of religious dogma. But they diverge sharply on spirituality. • Dawkins: Scientific awe replaces religion; mysticism is incidental. • Dennett: Religion is a natural phenomenon to be explained away. • Hitchens: Religion is a moral and political menace. • Harris: Religion's doctrines are false, but its contemplative core contains empirically accessible truths about consciousness. In effect, Harris attempts to domesticate spirituality within secular modernity. Whether this project succeeds—or merely repackages religious intuition in neuroscientific language—remains a live philosophical question. But within the New Atheist constellation, he alone consistently argues that one can be rigorously atheistic while still taking mystical experience seriously.

Comment Form is loading comments...

|