|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020). Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020). Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9 | Part 10

'As the world marks the centenary of the October Revolution, Russia is once again under the rule of the tsar.' (The Economist, 2017)

Is Putin the new Tsar?Stephen Kotkin on the Ukraine CrisisFrank VisserAbstract by ChatGPT. Frank Visser's article "IS PUTIN THE NEW TSAR?" examines the Ukraine crisis, presenting both mainstream and contrarian perspectives. The mainstream view sees Putin's invasion as unprovoked, while contrarians believe it's a response to NATO's expansion and Ukraine's actions. Historian Stephen Kotkin refutes the idea that the West instigated the crisis, emphasizing Russia's historical pattern of autocracy and suspicion. Kotkin suggests that Russia's autocratic tendencies will lead to Putin's downfall. The article also highlights Putin's evolution from a reasonable politician to a despot. Comparatively, Ukraine ranks better than Russia in corruption, democracy, and press freedom.

In sum, Ukraine, with all of its shortcomings, scores better than Russia in all three dimensions of corruption, democracy and press freedom.

We have published a slew of essays on the current Ukraine crisis in the past few weeks, covering both the mainstream view and its contrarians. In the mainstream view, Putin has started an unprovoked invasion of Ukraine last February, based on the dubious assumptions that Ukraine is ruled by Nazis who need to be destroyed and NATO-backed Ukraine forms a threat to Russia's security due to its future membership of NATO and/or the EU. The majority of the Western world has united to defend Ukraine against this unjustified attack—even though outside that circle of influence interest in this conflict is rather low. These "neutral" countries would do well to understand that the Russian invasion of Ukraine violated international law, even if it seems to be a European conflict to them. Time will come when they would want to refer to international standards as well. What if super powers can grab land whenever they feel like they have every right to do so, especially when their claim rests on romantic fantasies of a great past empire? The contrarian view is that Ukraine has attacked Russian-speaking Ukrainians in the Donbas for years, and Russia has finally come to their rescue, also because it is convinced Ukraine was planning a large scale attack on the Donbas. The NATO expansion in recent years is seen as another reason for this invasion, because every superpower tries to guard its borders against foreign influences. The contrarians also believe that the huge effort the West has initiated to support Ukraine, in the form of weapons and sanctions, will backfire, because it will escalate the conflict to possibly disastrous proportions, and it will hurt the Western economies which are at least for the moment fully dependent on Russian energy. Also, Russia will move away from Europe and seek alliances with China and other Asian or African countries, which will change the political landscape from a unipolar American hegemony to a multipolar world, in which various superpowers reign over their own spheres of influence. To support their views, the contrarians have quoted from various "realist" authors such as political analysts Kennan, Matlock, Basevic, Mearsheimer and Kissinger. Others have quoted from Russia-friendly conspiracy sources such as Russia Today or even more obscure websites. However, they have not yet contrasted these views with possible counter arguments. Are these realists really that realistic? COUNTERING CONTRARIANS Stephen Kotkin In a recent interview published in The New Yorker, historian and famous Stalin-biographer Stephen Kotkin responds to the often-heard claim that somehow the West is to blame for the current Ukraine crisis. I have only the greatest respect for George Kennan. John Mearsheimer is a giant of a scholar. But I respectfully disagree. The problem with their argument is that it assumes that, had NATO not expanded, Russia wouldn't be the same or very likely close to what it is today. What we have today in Russia is not some kind of surprise. It's not some kind of deviation from a historical pattern. Way before NATO existed—in the nineteenth century—Russia looked like this: it had an autocrat. It had repression. It had militarism. It had suspicion of foreigners and the West. This is a Russia that we know, and it's not a Russia that arrived yesterday or in the nineteen-nineties. It's not a response to the actions of the West. There are internal processes in Russia that account for where we are today.[1] Furthermore, he refutes the geopolitical logic of these "realists" by giving some wider historical perspective on Russia. In particular, he feels that NATO expansion has increased, and not decreased European security: I would even go further. I would say that NATO expansion has put us in a better place to deal with this historical pattern in Russia that we're seeing again today. Where would we be now if Poland or the Baltic states were not in NATO? They would be in the same limbo, in the same world that Ukraine is in. In fact, Poland's membership in NATO stiffened NATO's spine. Unlike some of the other NATO countries, Poland has contested Russia many times over. In fact, you can argue that Russia broke its teeth twice on Poland: first in the nineteenth century, leading up to the twentieth century, and again at the end of the Soviet Union, with Solidarity. So George Kennan was an unbelievably important scholar and practitioner—the greatest Russia expert who ever lived—but I just don't think blaming the West is the right analysis for where we are.[1] He also details why autocrats will in the end always undermine their own position, while they lose contact with reality, and only communicate with like-minded officials they trust. In the case of Russia, all Putin has to do is distribute the huge wealth he gains from his gas and oil exports to a few oligarchs around him, and in return they will not challenge his power. Hence he can stay in office indefinitely, as a true dictator will always try to arrange, by changing legislature that is exactly meant to prevent these long-term positions. In the meantime, the domestic econony will not prosper, and what is left is in fact a kleptocracy. By starting wars every now and then, those in power will boost their popularity, which is certainly the case for Putin after his annexation of Crimea and his invasion of Ukraine (and the same goes, incidentally for Zelensky, the media savvy comedian-turned-president, whose popularity was declining just before the invasion).

“Despotism creates the circumstances of its own undermining.” (Kotkin)[1]

While Kotkin explicitly denies that Russians are somehow innately inclined to imperialism and autoritarianism, he does think there is a pervasive pattern in Russian history when it comes to government styles, covering both the tsaristic times, the Soviet Union and the era of Putinism:

As he concluded, "There are internal processes in Russia that account for where we are today."[1] And these autocratic processes will in the end lead to the demise of Putin, though it will have costed thousands of lives and billions of damage in cultural heritage and infrastructure. In general, he perceptively says, "war usually is a miscalculation"[1], in which the strength of the invader is overestimated, and the resistance of the invaded underestimated. In the case of the Ukraine crisis we could also add: Putin severely underestimated the willingness of the Western countries to support Ukraine with heavy weapons. Even taking the Donbas seems to be too difficult for his army. And even if he "wins" that limited goal, the population will be divided as ever, and will be living among ruins. Not really a "victory" I would say. In various publications Kotke has traced how Russia has always tried to match the West, but has repeatedly and consistently failed. He elaborates: Russia is a remarkable civilization: in the arts, music, literature, dance, film. In every sphere, it's a profound, remarkable place—a whole civilization, more than just a country. At the same time, Russia feels that it has a "special place" in the world, a special mission. It's Eastern Orthodox, not Western. And it wants to stand out as a great power. Its problem has always been not this sense of self or identity but the fact that its capabilities have never matched its aspirations. It's always in a struggle to live up to these aspirations, but it can't, because the West has always been more powerful. Russia is a great power, but not the great power, except for those few moments in history that you just enumerated. In trying to match the West or at least manage the differential between Russia and the West, they resort to coercion. They use a very heavy state-centric approach to try to beat the country forward and upwards in order, militarily and economically, to either match or compete with the West. And that works for a time, but very superficially. Russia has a spurt of economic growth, and it builds up its military, and then, of course, it hits a wall. It then has a long period of stagnation where the problem gets worse. The very attempt to solve the problem worsens the problem, and the gulf with the West widens. The West has the technology, the economic growth, and the stronger military. The worst part of this dynamic in Russian history is the conflation of the Russian state with a personal ruler. Instead of getting the strong state that they want, to manage the gulf with the West and push and force Russia up to the highest level, they instead get a personalist regime. They get a dictatorship, which usually becomes a despotism. They’ve been in this bind for a while because they cannot relinquish that sense of exceptionalism, that aspiration to be the greatest power, but they cannot match that in reality. Eurasia is just much weaker than the Anglo-American model of power. Iran, Russia, and China, with very similar models, are all trying to catch the West, trying to manage the West and this differential in power.[1] In his view, Putin is no exception to this historical pattern, although society has of course greatly changed since the times of the Tsars. Yet, Put increasingly turns to that part of Russian history to concoct his favorite historical narrative, by aligning with the Russian Orthodoxy and referencing past saints or politicians. Kotke reminds us that Putin is definitely not (yet) someone in the league of mass-murderers Hitler, Stalin or Mao, but that he does fit the category of an autocratic ruler who might share the same fate.

Stephen Kotkin: Putin, Stalin, Hitler, Zelenskyy, and War in Ukraine | Lex Fridman Podcast #289

In an interview with podcast host Lex Fridman Kotke expands on his views in more detail. For example, he argues that there's no reason why Russia can't just live peacefully with its neighbours, if only it relinquishes its goal to match the West. I'm countering two arguments here. I'm countering one argument which is very deeply popular, pervasive about how Russia has this cultural tendency to aggression and it can't help but invade its neighbors and it does it again and again and it's eternal Russian imperialism and you have to watch out for it this very popular argument in the Baltic states. It's really popular in Warsaw, it's really popular with the liberal interventionists and it's it's very very popular with those who are part of the Iraq war squad that got us into that mess, so i'm against that and the reason i'm against it is because it's not true. It's empirically false. There is no cultural trait, no inherent tendency for Russia to be aggressive. It's a strategic choice that they make. Every time is the choice made. It's not some kind of momentum every time it's a choice that we should judge for the choice that it is for the decision and therefore they could make different choices. 'A TSAR IS BORN'

The kind of rule Mr Putin has gradually fashioned over his years in power has more in common with a tsar than with a Soviet politburo chief, let alone a democratically elected leader. (The Economist, 2017)[3]

I have just finished reading a recent Putin biography written by New York Times correspondent Steven Lee Myers, which is actually called The New Tsar: The Rise and Reign of Vladimir Putin, and came away with a more intimate understanding of Putin's psychology. How a shy boy from a lower class milieu for a long time showed no other ambition than becoming a kind of Russian James Bond spy. He managed to be sent to Dresden, where he did some wholly unremarkable KGB work. When the Berlin Wall fell, he felt deserted by the powers in Moscow, and returned to Russia. In Leningrad he became assistant to the mayor of that city, where he did all kind of behind-the-scenes work. When this mayor was removed from office he again felt lost. Due to fortunate connections he got into contact with Jeltsin, who was in bad health and looking for a successor. And then things went very fast. What becomes clear from this biography is that Putin has changed over time, during his 20+ years on-and-off regime, from a reasonable politician open to the West to a rather lonely and paranoid despot, who consciously models himself after the tsars of the past. In the post-Jeltsin years, his emphasis on efficiency and order was felt as a blessing, in a country that was rife with cowboy capitalists, but as time went by, he seems to have become the single embodiment of the Russian society's order. And that creates a paradox. Since very few critical voices are left, and Putin is surrounded by yes-man and old KGB-friends from his Leningrad days, there is no clear idea how a post-Putin period in Russian history would look like. And that seems to be a recipe for disorder, if not chaos. Only when Jeltsin turned him into presidential candidate almost overnight was there some sort of peaceful transfer of power (even though Jeltsin just appointed him). It is also interesting to read that Putin's rise to power and popularity coincided with the start of the second Chechen war. Nothing unites a country more than having an enemy. But that soon changed into its opposite when it turned out this was not a short and easy war (remember Kotkin's "war usually is a miscalculation"). The same happened when the Crimea was annexed, and again in February 2022 when the "special operation" started. One wonders how long Putin can sustain this current rise in popularity, when the number of casualties rises and the effects of sanctions set in. The Economist did various features on Putin in 2017, which are still relevant today. The authors explicitly state "A tsar is born" and point to his increasingly militaristic, authoritarian and repressive style of government.[2] But there's a paradox: the stronger Putin's position currently is, the more difficult will be to find a suitable successor for him and keep Russia together as a nation.[3] That too is a lesson he could learn from his predecessors. Is Putin the new Tsar? Well, he certainly would like to be one. And with some modern adjustments, he now plays the same role, sanctioned by the Orthodox Church. Perhaps a comparison with mafia dons is more appropriate, if one reads Catherine Belton's Putin's People: How the KGB Took Back Russia and Then Took On the West (2020) or Bill Browder's Freezing Order: A True Story of Money Laundering, Murder, and Surviving Vladimir Putin's Wrath (2022). These books paint a grim picture of a ruthless despot surrounded by loyal clan-members, who get filthy rich by stealing from the Russian fossil fuel economy, without profiting the people.

A CENTURY OF RUSSIAN COLONIALISMJoseph Dillard has argued in his recent essays that the United States has a long history of overthrowing foreign governments. His source lists 64 countries, from China to Ukraine, since the 1950's. Compared to this, the crimes of Russia (and not the Soviet Union) are non-equivalant, he claims. Contrary to this, even if we grant the differences between current Russia and the Soviet Union, an argument can be made that there is at least a century long tradition of "russian colonialism" that continues to this very day. Here's a list published by the Twitter account of "maksym.eristavi":

The list goes on and on and even goes back to the times of the Russian tsars, but the patterns are immediately obvious: Russia almost by second nature tries to keep neigbouring territories under control by installing Russia-friendly regimes, until popular uprisings result that are brutally crushed by the Russian army. Aren't we seeing this same pattern in Ukraine today? The invader's rationale will always be to "protect" its Russian-speaking citizens, but the effect is always that independence and democracy are crushed and the country is brought under the yoke of Russia. In the case of Ukraine, which has been independent for over 30 years now, this imperialist strategy seems to have failed badly. Of course, from the imperialist invader's perspective, the popular demonstrations are always seen as a threat, and it can't imagine these populations just want to be free and independent. Hence conspiracy theories about manufactured coups and support by foreign agents are standard. But it is first and foremost Russia that wants to have a strong grip on how these countries are ruled in the first place. Invaders always see themselves as "liberators", but the recipients of this treatment rarely do. Why would that be? Cynical political realists would say: but this is exactly how superpowers tend to behave. Welcome to the world of geopolitics! The question is: do we still tolerate this behavior today in 2022, when international relations are based on trade treaties and global communication? RANKING THE WORLDSome contrarians present a very favorably picture of Russian (and Chinese) society, compared to the West. It is well-known that Putin's ideologues see the West not only as materialist, but also as weak and decadent. The head of the Russian Orthodox Church Kirill once quipped that countries where Gay Pride parades are held are in the grip of Satan. This now has become a holy battle between Good (Eurasia) and Bad (the West). But this comparison with the West is terribly biased and unfounded. Let's have a look at some data that might give us an idea how Ukraine compares to Russia (and China) and to the rest of the world, when it comes to corruption, democracy and press freedom. I will present rankings for both Ukraine and Russia, for the United States, India and China, and the top and bottom extreme positions. I will also mention some countries with comparable ranking status. Ukraine is often labelled as a corrupt country that is governed by oligarchs, by those who defend or at least "understand" Putin, and that is definitely the case. But Russia fares even worse, as this overview shows. Russia is in the range of Mali or Myanmar, while Ukraine is more like Mexico and the Philippines, according to this ranking.[2]

Likewise, Zelensky is glibly caled undemocratic, when he silences the opposition (in times of war, mind you). Ukraine has a long way to go on the road to becoming a mature democracy, but it has at least clearly moved in that direction.

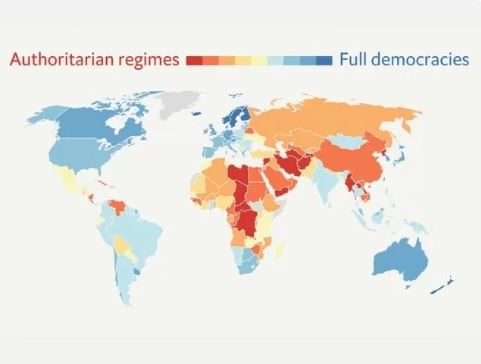

It is interesting to check the variaties of "democratic maturity" that are mentioned in this overview.[5]

This means, that the United States is no longer seen as a full democracy, but is officially given the label "flawed democracy". Ukraine is a "hybrid regime", but Russia and Belarus (and China) are definitely seen as "authoritarian".

More than a third of the world's population lives under authoritarian rule while just 6.4% enjoy full democracy.[5]

When it comes to press freedom, Ukraine is like Greece or Albania. Russia scores particularly bad (and China even worse, almost as bad as North Korea!). It is more like Afghanistan and Pakistan, whereas Ukraine resembles several African countries.

In sum, Ukraine, with all of its definite shortcomings, scores better than Russia in all three dimensions of corruption, democracy and press freedom. It is also striking that European countries consistently end up in the top end of these rankings, with Northern Europe always among the top 5, as you can see on this chart. It is often mentioned that "only" the West objects to Russia's invasion and the "rest" of the world either is neutral or supports it (although there are only 5 countries that go that far). One can even counter that these rankings are biased towards Western values, but then again, these are definitely values worth having I would say. If that means being "brainwashed by Western propaganda", give me more of that! It all boils down to this simple question: where would you want to live yourself? There's an interesting cultural twist to this democracy ranking, for if you ask people: do you think your country has enough democracy?, China scores remarkably high.[7] And even in democratic countries, people sometimes think their countries are not very democratic. It is a bit like wealth: one can feel poor in an objectively rich country and rich in an objectively poor country, when you compare yourself with your fellow citizens. So there's a strong subjective component to this issue as well. I wonder if that also goes for corruption or press freedom as well... There's also the fact that collectivistic cultures just don't value individual freedom of expression that much as more individualistic ones. That, of course, ties in with the integral model of stages of social development. It is a tragedy that Marxism took hold in agrarian and collectivistic countries, instead of the highly liberalized capitalist West. The phase of individual liberties is painfully lacking in those (post)communist societies. You just can't skip stages, as the saying goes. And if this all about a values clash, traditionalist cultures are hardly up to the task of seeing the value of individual freedom and secularism. They can only produce caricatures, as Putin has demonstrated, as if westerners are just weak and decadent... drugs using Nazis!

It all boils down to this simple question: where would you want to live yourself? (Source: www.jagranjosh.com)

Contrarian or conspiracy thinkers will argue that the United States is a corrupt country too, that its democracy fails and that the Main Stream Media prevent any dissenting views (on COVID-19 or Russia alike) to be published ("censorship!"), but the above world rankings put these complaints in a somewhat sobering perspective. That said, it's a fine line between dissident information and disinformation, as it was in the case of corona, it is now in the case of Russia's role in Ukraine. With war propaganda being in full force at both sides, it's hard to figure out who is right or wrong. All I know is that this is a senseless war that doesn't solve anything and the costs are tremendous. NOTES[1] David Remnick, "The Weakness of the Despot: An expert on Stalin discusses Putin, Russia, and the West", www.newyorker.com, March 11, 2022. [1a] Lex Fridman, "Stephen Kotkin: Putin, Stalin, Hitler, Zelenskyy, and War in Ukraine | Lex Fridman Podcast #289", www.youtube.com, 25 May 2022. [2] "A tsar is born", www.economist.com, Oct 26th 2017. [3] "Vladimir Putin wants to forget the revolution", www.economist.com, Oct 26th 2017. [4] "Corruption Perceptions Index 2021", www.transparency.org [5] "Democracy Index 2021", www.jagranjosh.com. Data from The Economist Intelligence Unit report (available only after registration), which uses the following definitions:

Full democracies: Countries in which not only basic political freedoms and civil liberties are

respected, but which also tend to be underpinned by a political culture conducive to the flourishing of

democracy. The functioning of government is satisfactory. Media are independent and diverse. There

is an effective system of checks and balances. The judiciary is independent and judicial decisions are

enforced. There are only limited problems in the functioning of democracies. [6] "Press freedom index 2021", RSF, Reporters without borders. [7] Allicance of Democracies, "The Democracy Perception Index 2021", Latana.com (only available after registration).

Putin: "We're taking back what is rightfully ours." (CNN, June 14, 2022)

Comment Form is loading comments...

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||