|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992). David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992).

THE STUDY OF CONSCIOUSNESS

Glimpses into the Life and Work of Great Thinkers in Neuroscience and Philosophy

Chalmers |

Changeux |

Chomsky |

Churchland, Paul |

Churchland, Patricia |

Crick |

Dennett |

Edelman |

Flanagan |

Humphrey |

Huxley |

Koch |

Leary |

Lilly |

McKenna |

Nagel |

Tononi

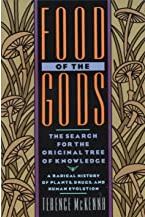

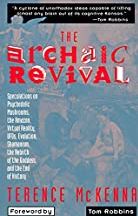

Terence McKennaYan XuTerence Kemp McKenna is an American philosopher, psychonaut, and ethnobotanist. His life was full of extraordinary adventures and ideas that many people considered radical and insane. He was one of the most famous pioneers in the field of human consciousness in the 20th century and was well known for his explorations of psychedelics.  Terence McKenna In the year of 1946, he was born in Paonia, Colorado. He is half Irish from his father's family and half Welsh from his mother's ancestry. In his early childhood, he was interested in fossil hunting and human history under his uncle's influence, which later on established his devotion to the complexity of language and history. He came upon an essay entitled “Seeking the Magic Mushroom,” which opened a door for him towards the study of human consciousness. McKenna also read Carl Jung writings at the age of ten, which fueled his interest in the field of psychology. In addition, according to the interview between Bodhi Tree Book Review's co-editor Mark Kenaston and McKenna in 1993, McKenna admitted that Aldous Huxley's The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell made him aware of psychedelic substances when he was a young teenager. As he stated in the interview, “I regard science fiction as the entry drug into the psychedelic world.” This interest motivated him to travel to Jerusalem and Nepal while he was enrolled in the University of California, Berkeley. In Jerusalem and Nepal, he continued his journey of curiosity by studying shamanism and psychoactive drugs, such as hashish. McKenna was fascinated by the internal experiences that Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) produced to him. Due to this reason, McKenna traveled with his brother Dennis to the Colombian Amazon in order to search for the oo-koo-hé, which is a plant that contains dimethyltryptamine. However, they did not find the plant; instead, they found the gigantic psilocybe cubensis mushrooms. In 1971, he returned back to the University of California and finished his study of shamanism and ecology. He also brought back the spores from Amazon, which allowed him to cultivate psilocybin mushrooms. He then published a book called Magic Mushroom Grower's Guide. According to McKenna, he believes that the mushrooms were found by the early proto-human primates who try to search for the new resources of food. In his book Food of the Gods, he claims since the mushrooms improve visual acuity and stimulate sexual desire, it actually increases reproduction success and is evolutionarily beneficial. Besides that, McKenna also points out that psilocybin is the catalyst for the human language and art: “All of the mental functions that we associate with humanness, including recall, projective imagination, language, naming, magical speech, dance, and a sense of religion may have emerged out of interaction with hallucinogenic plants.” McKenna advocates the usage of natural psychedelic substances, because he suggests that it takes people to a higher level of understanding the universal mysteries by elevating them to another dimension through hallucination. McKenna describes the experiences of hallucination as “a revelation of an alien dimension—a brightly lit, non-three-dimensional, self-contorting, linguistically intending modality that couldn't be denied.” Basically, he justifies the usage of psychedelic substances by stating that it opens the path of imaginations for the human to discover the truth of reality. In his book The Archaic Revival, he wrote, “Psychedelics are illegal because they dissolve opinion structures and culturally laid down models of behavior and information processing. They open you up to the possibility that everything you know is wrong.” Upon that, he also hypothesizes that psilocybin mushrooms might be a higher form of intelligence that makes human to reconsider their relationship between nature and man. Due to the early study of shamanism, McKenna was heavily influenced by the fractal patterns in Chinese philosophy of the I Ching, which later contributed to his theory of Timewave (Novelty Theory). According to John Major Jenkins' article Early 2012 Books, McKenna and Waters: “Terence advanced the notion that time is not a constant but has different qualities tending toward either 'habit' or 'novelty.' In the early 1970s, Terence developed a graph of time wave data based on I Ching's 64 hexagrams. He analyzed the “degree of difference” between each hexagram and find out the mathematical orders and “intentional construct” within I Ching. This study leads him to notice how time obtains certain behavior called “self-same similarity,” which means that its small section is identical to the future's larger event. Jenkin's article also concludes Terrance's novelty theory implies that “larger intervals, occurring long ago, contained the same amount of information as shorter, more recent, intervals. History was being compressed, moving quicker. And the process had to have an end.” This theory helps him identifies the date of the ultimate end of the process; he decided to choose 1945's atomic explosion as an “extremely novel” date for human history and predicted that the final phase would happen in 2012, which corresponds with Mayan calendar's prediction of cataclysmic events. Although McKenna was known as a pioneer in the field of psychedelics, McKenna faced a lot of criticism for justifying the usage of such drugs. Others, however, lauded his efforts; the article “Terence McKenna, 53, Dies; Patron of Psychedelic Drugs” by Douglas Martin wrote that Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead said that he was "the only person who has made a serious effort to objectify the psychedelic experience. McKenna was one of the few pioneers who saw the future of virtual reality and the Internet in the 1990s. According to the article “Terence McKenna's Last Trip” by Davis Erik, Terrence observed that psychedelic cultures would become common on the Internet. He argued, "Psychedelics were always about information...Their very existence was forbidden knowledge at one point. You had to be Aldous Huxley to even know about them." Unfortunately, McKenna died at the young age of 53 in the year 2000 due to brain cancer. However, his work has become even more widely known today and his influence how grown exponentially over the past two decades. Further Reading1. Food of the Gods: The Search for the Original Tree of Knowledge A Radical History of Plants, Drugs, and Human Evolution, Bantam; Reprint edition (January 1, 1993 2. True Hallucinations, HarperOne; Reprint edition (April 22, 1994) 3. The Archaic Revival: Speculations on Psychedelic Mushrooms, the Amazon, Virtual Reality, UFOs, Evolution, Shamanism, the Rebirth of the Goddess, and the End of History, HarperCollins; 1st edition (May 8, 1992)    Terence McKenna's

|