|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992). David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992).

THE STUDY OF CONSCIOUSNESS

Glimpses into the Life and Work of Great Thinkers in Neuroscience and Philosophy

Chalmers |

Changeux |

Chomsky |

Churchland, Paul |

Churchland, Patricia |

Crick |

Dennett |

Edelman |

Flanagan |

Humphrey |

Huxley |

Koch |

Leary |

Lilly |

McKenna |

Nagel |

Tononi

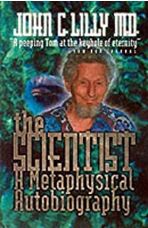

John LillyJoseph Perez“In the province of the mind, what one believes to be true, either is true or becomes true within certain limits. These limits are to be found experientially and experimentally. When the limits are determined, it is found that they are further beliefs to be transcended. In the province of the mind, there are no limits.” American neuroscientist John Cunningham Lilly is most often remembered for his research with dolphins and for the development of sensory deprivation tanks. Born on January 6, 1915, he was a counterculture scientist who frequently incorporated the usage of LSD and other psychedelic drugs in his experiments and theories. Because of his at times questionable experimentations, Lilly consistently faced public criticism as well as scientific skepticism with regards to his work.  John Lilly After receiving his medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania, through which he gained an interest in the field of biophysics, John C. Lilly joined the National Institute of Mental Health and began experimenting on the brain in pursuit of “the conscious self”. Soon after he began development on the sensory deprivation chamber in response to a puzzle posed by scientists about human consciousness. The puzzle concerned whether the human awareness required external stimulation through the physical body in order to be maintained. The answer provided by the sensory deprivation chamber? No, consciousness did not depend on physical stimuli. Essentially, Lilly managed to replicate sensory isolation by filling a tank full of warm salt water in a dark and soundproof room. Once he had mastered this procedure, he would begin experimenting and theorizing on the topic of consciousness in other species. While he experimented (usually on himself) with LSD and the sensory deprivation chamber (sometimes combining both), Lilly would go on to formulate his theories about the almost unlimited range of human cognition. Initially, much of his experimentation was on dolphins (for which he received a large grant from NASA), and he became famous for emphasizing the mammals' extraordinary intelligence. His work also formed the intellectual basis of two famous Hollywood movies: The Day of the Dolphin and Altered States. Lilly formulated his own views on consciousness through a growing understanding of Buddhist meditative practices and his revelations about his own LSD and ketamine use. In his book published in 1968, Programming and Metaprogramming in the Human Biocomputer: Theory and Experiments and The Center of the Cyclone, Lilly describes what he calls the human biocomputer which compares human biology to the hardware and software of a computer. He divides the perceivable reality into eleven different levels. Level one contains external forces such as heat and sound. Level two contains the body's system and functions. Level three contains the brain and its biochemistry. Level four is the neural activity. Level five through ten are essentially the memory storage and the programs of the human biocomputer. Levels past ten are left purposefully unknown by Lilly so that further developments into the theory can be inserted with future research. He often left many of his theories open for future input and the possibilities to be expanded upon as he often thought about the implications and future uses of his findings and developments. In many ways, he believed that the physical body was hindering the otherwise limitless brain's ability to transcend and perceive beyond the body's limitations. To solve this, he believed sensory deprivation tanks as well as drug use would allow the user to think beyond their biological limitations. In his 1978 book, The Scientist, Lilly predicted that there will come a time where humans will develop a new kind of intelligence through technology. However, he describes it as a mixture of both biology and technology which he believed would lead to catastrophic consequences and conflicts in the future as a debate between consciousness and ethicality would ensue. It is important to note that some of his most controversial ideas have stemmed from drug induced visions. Lilly believed that there exists a group called the Cosmic Coincidence Control Center within which there exists a subgroup called the Galactic Coincidence Control within which there also exists a subgroup which is called the Earth Coincidence Control Center. His attempt to explain and experience coincidence requires the user to be aware and follow nine different rules, the last of which is a motto that reads: "Cosmic Love is absolutely ruthless and highly indifferent: it teaches its lessons whether you like/dislike them or not." Additionally, Lilly was also a part of the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence project where techniques to detect evidence of intelligence outside of the solar system were discussed. During this project, the Drake Equation was heavily discussed. After the dissolution of the experiment for which he is most known, on dolphin language and communication, Lilly futilely attempted to communicate with dolphins using methods such as telepathy. The nature of his work garnered controversy in the scientific community due to his drug use as well as the radical work he conducted with dolphins. For example, when he revealed that he had been giving doses of LSD to his dolphin test subject at the Communication Research Institute, which he founded, on the island of St. Thomas, he suggested that the dolphins became more communicative. The experiment has been panned and described as an ethical “failure.” Part of the controversy revolved around the treatment of a dolphin by a female researcher, who did not discourage the sexual feelings the dolphin developed for her. Researchers of dolphin communication severely disagree with Lilly's procedures and findings, although the original hypothesis that dolphins may have the cognitive ability for human-like language skills has now found more substantive evidence to support it. Despite the condemnation around this treatment of his subjects, Lilly's experiments brought public awareness to the intelligence of dolphins, which are, consequently, now regarded as one of the most intelligent mammals on earth. In contemporary society, research into the intelligence of dolphins continues largely as a result of the work of John C. Lilly. Lilly died on September 20, 2001, of heart failure.

John Lilly Explains His Ideas

1. There was a problem in neurophysiology at the time: Is brain activity self-contained or not? One school of thought said the brain needed external stimulation or it would go to sleep—become unconscious—while the other school said, “No, there are automatic oscillators in the brain that keep it awake.” So I decided to try a sensory-isolation experiment, building a tank to reduce external stimuli—auditory, visual, tactile, temperature—almost to nil. The tank is lightproof and soundproof. The water in the tank is kept at ninety-three to ninety-four degrees. So you can't tell where the water ends and your body begins, and it's neither hot nor cold. If the water were exactly body temperature, it couldn't absorb your body's heat loss, your body temperature would rise above one hundred six degrees, and you might die. I discovered that the oscillator school of thought was right, that the brain does not go unconscious in the absence of sensory input. I'd sleep in the tank if I hadn't had any sleep for a couple of nights, but more interesting things happen if you're awake. You can have waking dreams, study your dreams, and, with the help of LSD-twenty-five or a chemical agent I call vitamin K, you can experience alternate realities. You're safe in the tank because you're not walking around and falling down, or mutating your perception of external “reality.” 2. The brain has other pleasure systems, too—systems that stimulate nonsexual pleasure all over the body and systems that set off emotional pleasure. That is a kind of continuous pleasure that doesn't peak—a satori of mind. Satori and samadhi [terms for enlightened-bliss states in Zen Buddhism and Hinduism, respectively] and the Christian “states of grace” seem to involve a constant influx of pleasure and no orgasmic climax—like tantric sex. Spiritual states use these brain systems in their service. Many philosophers, including Patanjali, the second-century B.C. author of the Yoga Sutras, have said that jnana yoga—the yoga of the mind—is the highest form of yoga. In this self-transcendence one can experience bliss while performing God's work; only recently have I achieved this for days at a time. 3. Yes, the experience of higher states of consciousness, or alternate realities—I don't like the term altered states—is the only way to escape our brains' destructive programming, fed to us as children by a disgruntled karmic history. Newborns are connected to the divine; war is the result of our programmed disconnection from divine sources. I am writing a book about alternate realities called From Here to Alternity: A Manual on Ways of Amusing God. On vitamin K, I have experienced states in which I can contact the creators of the universe, as well as the local creative controllers—the Earth Coincidence Control Office, or ECCO. They're the guys who run the earth and who program us, though we're not aware of it. I asked them, “What's your major program?” They answered, “To make you guys evolve to the next levels, to teach you, to kick you in the pants when necessary.” Because our consensus reality programs us in certain destructive directions, we must experience other realities in order to know we have choices. That's what I call Alternity. On K, I can look across the border into other realities. I can open my eyes in this reality and dimly see the alternate reality, then close my eyes. and the alternate reality picks up. On K you can tune your internal eyes. They are not what is called the “third eye,” which is centrally located, but are stereo, like the merging of our two eyes' images. Perhaps someday, if we learn about the type of radiation coming through those eyes, we can simulate the experience with a hallucinatory movie camera—an alternate-reality camera. 4. You know, [Kurt] Gödel's theory, translated, says that a computer of a given size can model only a smaller computer; it cannot model itself. If it modeled a computer of its own size and complexity, the model would fill it entirely and it couldn't do anything. So I don't think we can understand our own brains fully.[1] NOTES[1] "John Lilly on Dolphin Consciousness", Omni Magazine, October 12, 2017

Further Reading1. The Center of the Cyclone: An Autobiography of Inner Space, Float On (January 6, 2017) 2. The Scientist: A Metaphysical Autobiography, Ronin Publishing, Inc.; 3rd edition (October 23, 1996) 3. Simulations of God: The Science of Belief, Simon & Schuster; 1st edition (June 4, 1975)    MSAC PHILOSOPHY GROUP

Human interest in the nature of consciousness dates far back to our ancestral past. However, it is only in the last century or so that researchers and philosophers have been able to tackle the problem in a more scientific way. This is primarily due to our increasing understanding of human physiology and how our brain functions. With the advent of ever more sophisticated technology—from fMRI scans, functional magnetic resonance imaging, to DARPA's neural engineering program, understanding neural “dust”—we are now able to not only create vivid simulations of cerebral activity but also to systematically reverse engineer the brain. Whether such empirical observations will unlock the secrets of self-reflective awareness is still open to vigorous debate. Nevertheless, the study of consciousness is now considered to be of elemental importance and has invited a large number of brilliant thinkers— from a wide range of disciplines, including mathematicians, quantum physicists, neuroscientists, and philosophers—to join in the discussions and offer their own contributions. The following essays briefly explore the life and work of pioneers in the field of consciousness studies. Included in this eclectic mix are such notables as Giulio Tononi (University of Wisconsin), Paul and Patricia Churchland (University of California, San Diego), Noam Chomsky (M.I.T.), the late Timothy Leary and Terence McKenna, and Jean Pierre Changeux (Collége de France) among others.

Comment Form is loading comments...

|