|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992). David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992).If there's a singular topic Integral students need to be educated on it is evolutionary theory, given their frequent but uninformed use of the term "evolution". These short biographical chapters about evolutionary theorists have been written by different philosophy students of professor David Christopher Lane. (FV)

THE EVOLUTIONARY SCIENTISTS

Glimpses into the Life and Work of Great Thinkers in Evolutionary Biology

Coyne|

Crick|

Darwin|

Dawkins|

Diamond|

Dobzhansky|

Eldridge|

Gould|

Haldane|

Hamilton |

Lamarck|

Lovelock|

Mayr|

Mendel|

Monod|

Spencer|

Trivers |

Wallace |

Weismann |

Williams |

E.O. Wilson

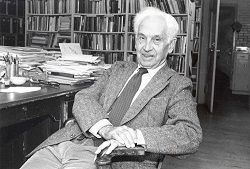

Ernest Walter MayrCaptoria FrizellErnest Walter Mayr was one of the leading evolutionary biologists of the 20th century. He studied ornithology, systematics, and the philosophy of biology and was a world-renowned taxonomist. He was born in Kempten, Bavaria, Germany on July 5th, 1904. He was the 2nd son of Helene Pusinelli and Dr. Otto Mayr. His father was a district prosecuting attorney at Wurzburg but was heavily interested in natural history and shared his passion with his children by taking them to the museum often. Mayr's older brother, Otto, taught him about the birds of Wurzburg; this contributed to Mayr's passion for history and ornithology.  Ernest Walter Mayr At about age 13, Mayr's father died and the family relocated to Dredsden, Germany where he completed high school, joined the Saxony Ornithologists' Association, and met his ornithological mentor Rudolf Zimmerman. He started studying medicine at the University of Greifswald, but after a year decided to pursue his passion of ornithology and began studying the biological sciences. According to Mayr, Greifswald was the most ornithological interesting place, which why he chose to go to the school. He completed his doctorate at the University of Berlin in June 24, 1926 at the age of 21 and began to work at the Berlin Museum. In 1927, Mayr was recruited by Walter Rothschild to study in New Guinea, where he named 26 bird species, 38 orchid species and collected thousands of bird skins. According to the Britannica website library, in 1931, he began working in the American Museum of Natural History as the curator of the ornithological department. He mentored many young American bird watchers and heavily influenced American ornithological research. He played a key role in the publishing of Margaret Morse Nice's 2 volume Studies in the Life History of the Song Sparrow and encouraged members of the Linnean Society, who he also relied on heavily for friendship in New York, to take on research projects of their own. He worked tirelessly to unite American and European Ornithological studies and continuously corresponded with Joseph Grinnell to have foreign literature reviewed in the Condor, which is a scientific journal that covers ornithology. He did face backlash and heckling from the Bronx County Bird Club; however, it did not stop him. In 1953, he became a faculty member of Harvard University. He served as the director of the Museum of Comparative Zoology from 1961 to 1970. He retired with honors in 1975 as emeritus professor of zoology. After retirement he continued to publish articles in numerous magazines. He died on February 3, 2005 in Bedford, Massachusetts. Although his wife passed away in 1990, he is survived by two daughters, five grandchildren and ten great grandchildren. He lived to be 100 years old. Ernst Mayr was very fond of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution of natural selection which states that “More individuals are produced each generation that can survive, phenotypic variation exists among individuals and the variation is heritable, those individuals with heritable traits better suited to the environment will survive and when reproductive isolation occurs, new species will form”, Accordingly, Darwin believed that many species could evolve from more than one common ancestor which created the species problem. Mayr explained and simplified the species problem by stating that “A species is a group of morphological similar individuals that can only breed amongst themselves”. This was also an elaboration on Darwin's perception of the unity of life which stated that “All organisms are related through descent from an ancestor that lived in the distant past”. Mayr believed deeply that Darwin's theory explained why genes evolved at the molecular level. Mayr was also heavily influenced by Gregor Mendel's theory of genetics which is broken into three different laws: “The Law of Independent Assortment which states the traits inherited through one gene will be inherited independently of the traits inherited through another gene because the genes reside on different chromosomes that are independently assorted into daughter cells during meiosis; The Law of Segregation which states in the second of the two cell divisions of meiosis the two copies of each chromosome will be separated from each other, causing the two distinct alleles located on those chromosomes to segregate from one another; and The Law of Dominance which states that if one parent has two copies of allele A—the dominant allele—and the second parent has two copies of allele a—the recessive allele—then the offspring will inherit an Aa genotype and display the dominant phenotype.” Mayr was so heavily influenced by these two theories he became one of the leading contributors of the modern synthetic theory of evolution, which combines the biological processes of gene mutation and recombination, changes in the structure and function of chromosomes, reproductive isolation, and natural selection. Mayr believed that populations within a species may differ due to geographical isolation, feeding strategy and mate choice. He used evidence from his ornithological studies to display this. Mayr believed that researchers should study the complete genomes of a species more so than the isolated genes. He believed that population thinking replaced essentialism and that materialistic processes explained the impression of design. He heavily criticized the search for Extra Terrestrial Intelligence due to the groups searching for them inability to address specific scientific questions. In fact, he thought it was a complete waste of time. He was a firm believer of the scientific method. Yet, he had his disagreements. In an interview on Edge.org, Mayr explained, “Well, Darwinism will not have to do any going, because it's already here. In the last 50 years, ever since the "Evolutionary Synthesis" of the 1940s, the basic theory of Darwinism has not changed, with perhaps one exception, that is the question of the target of selection. What's the object of a selective act? For Darwin, who didn't know any better, it was the individual—and it turns out he was right. Some very influential and notable books Mayr wrote are What Makes Biology Unique, The Principles of Systematic Zoology, and One Long Argument: Charles Darwin and the Genesis of Modern Thought. Notes[1] "Ernst Mayr: What Evolution Is", Introduction by Jared Diamond, www.edge.org, 2010. Further Reading1. What Evolution Is, (Science Masters Series), Basic Books; Reprint edition (October 11, 2002). 2. The Growth of Biological Thought: Diversity, Evolution, and Inheritance, Belknap Press: An Imprint of Harvard University Press; 62159th edition (1982). 3. One Long Argument: Charles Darwin and the Genesis of Modern Evolutionary Thought (Questions of Science), Harvard University Press (March 15, 1993).    MSAC Philosophy Group

The theory of evolution has a long history. However, it was not until Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace discovered that the wide variety of species we presently see were largely the result of natural selection did evolutionary studies have a solid, scientific basis. In the past one hundred and sixty years, a number of eminent biologists have contributed to our understanding of how complex life forms emerged from simpler, more rudimentary ones.

Comment Form is loading comments...

|