|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Dr. Joseph Dillard is a psychotherapist with over forty year's clinical experience treating individual, couple, and family issues. Dr. Dillard also has extensive experience with pain management and meditation training. The creator of Integral Deep Listening (IDL), Dr. Dillard is the author of over ten books on IDL, dreaming, nightmares, and meditation. He lives in Berlin, Germany. See: integraldeeplistening.com and his YouTube channel. He can be contacted at: [email protected] Dr. Joseph Dillard is a psychotherapist with over forty year's clinical experience treating individual, couple, and family issues. Dr. Dillard also has extensive experience with pain management and meditation training. The creator of Integral Deep Listening (IDL), Dr. Dillard is the author of over ten books on IDL, dreaming, nightmares, and meditation. He lives in Berlin, Germany. See: integraldeeplistening.com and his YouTube channel. He can be contacted at: [email protected]

SEE MORE ESSAYS WRITTEN BY JOSEPH DILLARD Toward PolycentrismPart 3: Differentiating Varieties of PolycentrismJoseph DillardOur identity is formed and maintained largely by the different perspectives we encounter in life. These in turn generate our sense of control, life direction, meaning, and our relationships with others. This essay series explains varieties of this fundamental and adaptive ability and how limitations in how we approach perspectives can go wrong, creating undue personal suffering and even societal collapse. In the first two essays in this series cognitive and experiential multi-perspectivalisms were differentiated and the difference between psychological geocentrism, heliocentrism, and polycentrism were explained. We will now look at two varieties of transpersonal experiential multi-perspectivalism, those that are phenomenologically-based and those that are not. What is a phenomenological approach?“Phenomenological” is here used to refer to the objectification, observation, and investigation of the contents of awareness: thoughts, feelings, cognition, and consciousness itself. Classically, beginning with Husserl, phenomenology involves practices and experiences that are primarily interior and personal, such as investigating how thoughts arise, the nature and processes of cognition. Meditation is obviously a phenomenological discipline, primarily a combination of religious/spiritual/methodological doctrine and practice. Husserl's phenomenology is primarily a combination of philosophy and metacognition, or thinking about thinking, combined with an actual practice of observation of the contents of awareness. Polycentric phenomenology understands and takes philosophical and metacognitive perspectives into account, but it is not primarily about either one. Instead, it focuses on observation of interior collectives and their interaction. This means that it is much more associated with the interior collective quadrant of holons than is classical phenomenology or meditation.

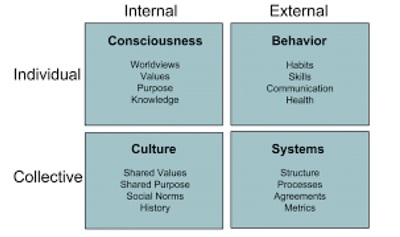

(Source: “Integral Center Membership Manual”)

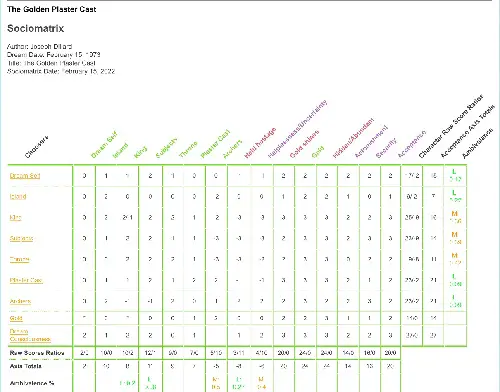

For example, our worldview is our personal culture, including our values, purpose, social norms, and historical conditioning via exposure and internalization of multiple perspectives. Clearly, a great deal of our identity is interior and collective because it is comprised of our thoughts, emotions, worldview, and values as well as a multiplicity of social roles. The “sharing” aspect in the interior collective is not only with other individuals but the interaction and interdependence of different perspectives that co-exist both within us and autonomously, as represented by both physical and mental objects, including dream and waking imagery. This is a form of both phenomenology and polycentrism which encompasses more traditional understandings but enlarges on them in various ways, as we shall see. How and why cognitive multi-perspectivalism is not polycentricAs noted in the previous essays, integral cognitive multi-perspectivalism is not polycentric. It is indeed grounded in experiential multi-perspectivalism, most of it prepersonal, but some of it transpersonal and mystical. In the most prosaic sense, our cognition is grounded in our lived experience, and in that way all cognitive multi-perspectivalism is experience-based. Mystical and near death experiences leading to a radical redefinition of oneself and the meaning of life are highly convincing examples of experiential multi-perspectivalism. We generally justify our worldview based on our lived experience and conclude it is multi-perspectival because we have examined multiple alternative historical, traditional, non-traditional, moral, immoral, and amoral perspectives. Because our map is accurate, we are confident we know the territory. However, not having actually walked it, our confidence is not experientially based. We have multiple perspectives of the elephant but have not actually become the elephant and so have not experienced its identity and worldview. Polycentrism confronts our worldview, with its intrinsic biases and framings of reality, with one or more worldview that may be foreign, autonomous, or downright contrary to our own. Our normal response is to ignore, repress, or assert control over such challenges to our worldview, because they confront and threaten our identity. None of those responses are transpersonally multi-perspectival, because they prioritize defense of the self or Self over disidentification from it and immersion in a foreign or threatening perspective. It is possible that some alternative perspective, perhaps as a result of getting a serious case of Covid or facing food and heating price inflation due to the blowback from sanctions on Russia, may force us out of the assumptions of our worldview, but it is not likely. More likely responses, when confronted by “not-self” perspectives include justifications and rationalizations designed to maintain our worldview and reduce cognitive dissonance. We are more likely to tell ourselves, “I got Covid but it's no worse than the flu,” “Chinese stats lie; Western Covid deaths are not really hundreds of times greater than those of China,” or “The higher prices I am paying are Putin's fault and due to Russian aggression.” Those who present non-group or outgroup perspectives are likely to be ignored or censored by those identified with a psychologically geocentric worldview, including cognitive multi-perspectivalism. Anyone voicing perspectives outside of the accepted narrative and basic assumptions of the Israeli, Zionist, or Judeo-Christian worldview or gender wokeness risks ostracism or worse, providing powerful examples of how multi-perspectivalism on third rail topics can simply be disallowed by entire societies. Anyone voicing a contrarian view of Integral is likely to be labeled “red,” “blue,” “orange,” or a “green” caught in a performative contradiction.[1] Cognitive multi-perspectivalism is easily assumed to be transpersonal when it is notWesterners, progressives, liberals, and Integralists, as demonstrated by a remarkable consensus in collective groupthink, are on the whole convinced that they understand Putin and Xi, Russian and Chinese motives and character, and that both are in fact aggressive autocracies. That perspective must be upheld, because to challenge it creates cognitive dissonance by threatening Westerner's collective historical and personally scripted identity. It also threatens core assumptions about morality by which we differentiate good from evil. However, the spectacular inflationary and socially disruptive blowback of Western sanctions on Russia is demonstrating that Westerners only possess cognitive multi-perspectivalism, at best, and that very few have demonstrated polycentrism toward events in Ukraine, Russia, or China. Basic assumptions, including that Russia and China are dependent on the West, that they will collapse under the economic stress of sanctions, military pressure, and ostracism, have proven to be not only false but catastrophically mistaken and self-destructive misperceptions that are inviting Western sociocide. The problem is that groupthink consensus generally validates and expands our stuck, heavily defended psychologically geocentric identity. While most near-death experiences tend to validate psychological geocentrism in the form of reinforcing familial and socio-cultural scripting, mystical experiences expand our psychological geocentrism as psychological heliocentrism. The near-death experiences of Christians and even some non-Christians are likely to confirm that there is a God and Jesus is his son and our savior; our mystical experiences expand our identity to be one with all, thereby convincing us that we know universal truth. We are still ourselves, but that identity is now one with everyone and everything. Mystical immersions in oneness are typically experienced as compassionate and transformational. Both mystical and near death experiences, although they are varieties of experiential multi-perspectivalism, do not generate a dissociation from our worldview in the way that identification with multiple ignored, disowned, discounted, or threatening others do. For example, specific dream elements are generally interpreted as symbols, meaning we project our associations onto them, or they are ignored, disowned, discounted, or experienced as threatening. Objects like teaspoons and pavement are generally ignored, disowned, and discounted as perspectives to become, respect, and listen to because, after all, they are mundane and utilitarian. Why become them? Why speak from their perspective? What could they possibly have to tell us about our life issues? Fantasy images, such as unicorns and the Cookie Monster are also generally ignored, disowned, and discounted, since they do not merit equal ontological standing with ourselves and do not personify equally valid worldviews. However, we do not know that to be the case; we simply assume it to be, not only because we lack a method by which to test our assumption, but because we depend on our pretense of control and need to continue to believe we possess a realistic, adequate worldview. Similarities between phenomenologically-based and non-phenomenologically-based approachesPhenomenologically-based multi-perspectivalisms (PEMs) have several qualities that non-phenomenologically-based transpersonal and experiential multi-perspectivalisms (non-PEMs) do not. But first, let us consider their similarities. First, PEMs and non-PEMs are both polycentric rather than psychologically geocentric or heliocentric. This does not mean that they do not include and use geocentrism, and even possibly heliocentrism; they can and may do so. Both varieties practice the radical decentralization of both worldview and identity. Secondly, both are primarily experiential, which makes them superficially appear to be forms of prepersonal multi-perspectivalism, when in fact they are transpersonal. For example, interviewing and becoming dream characters can easily be viewed as being a prepersonal dive into pure subjectivity. The same can be assumed regarding respect for belief systems that integralists generally discount as “red” (tribal) or “blue” (cultish/nationalistic). Third, while both are primarily experiential, they contain cognitively multi-perspectival components. While both PEMs and non-PEMs focus on walking a non-self territory, they use maps. Fourth, both are primarily transpersonal, that is, they transcend identification with the self or Self. Fifth, they are integral, but in a broader sense than Wilber's integral AQAL, because while AQAL views the transpersonal as a realm of Self-realization, that is, of psychological heliocentrism, polycentrisms do not. Differences between phenomenologically-based and non-phenomenologically-based approachesRegarding the differences between non-phenomenologically-based and phenomenologically-based experiential multi-perspectivalisms, the former involves experiential immersion in one or more non-self, non-ingroup collective lifestyle and culture. It could be a religious sect or cult, a political party, or an entirely different nation. A collection of gamers or some subset within one's worldview does not qualify. For example, while Tom Cruise is a Scientologist, his worldview is fundamentally that of US groupthink with an assortment of whackiness sprinkled on top. As different as they are, Donald Trump, Joe Biden, Roger Waters, Benjamin Netanyahu, and Steven Pinker are all representatives of the same collective western groupthink. That's not polycentrism but rather psychological geocentrism with specific cultish dogmas, ideologies, and intellectual worldviews integrated into it. By contrast, immersion in Iranian, Palestinian, Chinese, or Russian cultures, including adopting their worldviews, is an example of non-phenomenological experiential multi-perspectivalism. PEMs may include non-PEMs, but do not require immersion in non-ingroup societies and culture. Secondly, while both PEMs and non-PEMs assimilate non-self identities to a broad identity that remains largely psychologically geocentric, non-PEMS do so to a greater extent; one remains more closely identified with their psychologically geocentric identity and worldview. For example, as we shall see in the example below, Scott Ritter assimilates the Russian worldview to an underlying American, socially and familial scripted worldview. PEMs, on the other hand, are more likely to appear downright bizarre, irrational, absurd, or even threatening to ingroups. Third, non-PEMs typically deal with immersion in alternative societies and cultures with non-ingroup worldviews while PEMs may or may not do so, and instead focus on immersion in alternative intrasocial perspectives of dream characters, elements from fantasy, waking personal or geopolitical events, history, fiction, mystical and near-death experiences, synchronicities, or the personifications of current life issues. Fourth, non-PEMs generally do not require and generally do not possess a methodology. You just go somewhere, take some hallucinogen, altered state of consciousness, or enter some channeled, spiritualistic, near-death, or mystical state.[2] Non-PEMs can be an organic expression of a life in progress. You move or end up in a radically different culture or society and find your worldview and identity vastly expanded. PEMs, on the other hand, have a structured discipline or yoga of disidentification with self/Self and identification with a broad variety of non-self others.[3] Fifth, non-PEMs generally immerse deeply and completely in this or that outgroup perspective and worldview for an extended period of days, months, or years. You join a non-group collective or move to a very foreign country and experience both immersion and enmeshment. For example, if I had moved to China from the US that would have probably qualified as a non-PEM experience for me. However, I moved to Germany, and except for the language, the social and cultural fabric is essentially the same as the US. It doesn't qualify (for me) as a non-PEM dive into polycentrism. PEMs, on the other hand, immerse deeply, completely, and repeatedly in a multitude of outgroup perspectives, but for shorter periods of time, say half an hour. Sixth, PEMs are much more radically polycentric than non-PEM experiential multi-perspectivalisms. This is because disidentification with self/Self and identification with not-self outgroup perspectives is broader and more varied, with many more candidates for practice than occurs for non-PEM experience. An example of non-phenomenologically-based experiential multi-perspectivalism Scott Ritter The life experience of US Marine Scott Ritter provides a notable example of experiential multi-perspectivalism that is neither prepersonal, nor is it phenomenologically based. It is probably best categorized as a personal variety of experiential multi-perspectivalism. Growing up in a military family, Ritter hated Russians because he was scripted to not only believe, but to know that Russians were aggressors and a threat to his country and values. To defend both, he became a marine and studied Russian history and culture at depth to know his Russian enemies so he could more effectively kill them. He served as the lead analyst for the Marine Corps Rapid Deployment Force concerning the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the Iran-Iraq War. From 1991 to 1998 Ritter ran intelligence operations for the United Nations Special Commission (UNSCOM), which was charged with finding and destroying all weapons of mass destruction and WMD-related manufacturing capabilities in Iraq. Earlier, from 1987 through 1989, Ritter served as a weapons inspector in the Soviet Union, implementing the INF Treaty, supervising the on-site dismantling and destruction of nuclear capable ballistic missiles. During that time, Ritter got to know Russians as individuals and fellow humans. As a result, he shifted from hating Russians to respecting them. Ritter moved from an abstract, objectified cognitive multi-perspectivalism, based on his scripted familial and socio-cultural groupthink, itself an expression of prepersonal experiential multi-perspectivalism, to an embodied, experiential multi-perspectivalism. That is, he could remain a patriotic American, espousing its worldview and values, and be willing to kill Russians, while at the same time possessing the ability to look out at the world from the perspective of Russian citizens and their interests. By doing so, Ritter became an enemy of the commonly accepted collective groupthink narrative about Russia.[4] Integralists and other practitioners of cognitive multi-perspectivalism have a strong tendency to misperceive this variety of experiential multi-perspectivalism as adoption of a foreign, oppositional, or threatening perspective (“Ritter is a propagandist for Russia”) and then discount its legitimacy. This is a subset of the general tendency to misperceive the expression of any perspective that threatens psychological geocentrism as wrong or threatening. Experiential multi-perspectivalism and moral injuryHere is a different type of example, from the war in Ukraine, of how experiential multi-perspectivalism can be forced upon the unwilling, in a direct attack on their socio-cultural scripting. In this war, Americans are fighting against Europeans. In the Global War on Terror conflicts, Americans have benefited from experiencing an ingroup/outgroup phenomenon. In other words, they have been able to easily psychologically distinguish themselves from the enemy. That is beneficial to warfighters because it is easier to dehumanize an enemy if they do not look or act like you. When fighting in the Middle East or North Africa, it may have been possible to create a dissociation because the enemy “is not like us.” This is not the case in Ukraine. This situation is exemplified in another purported quote from a U.S. volunteer on the ground: It's feeling like my days are numbered and I'd like to say some things. About me. Former military. Afghanistan veteran. Combat experienced. Three days ago I was in a trench line listening to artillery. I got to thinking about the perspective of the enemy. Just a few hundred yards away are the Russians. Living through the same bullshit I am… I've seen dead bodies before. Dead Taliban. Dead Afghan civilians. But that culture was so far removed and different from ours that I couldn't really identify with it. I saw some dead Russians lined up by the road and I was shocked. I thought, 'These guys could be me.'[5] Moral injury, which occurs when an individual experiences or witnesses an event that contradicts their core moral values or beliefs, was part of the experience of the soldier quoted above. Moral injury is not always a simple matter of determining what is moral and what isn't. When Russia invaded Ukraine, to not support Ukraine in the war outraged many people because for them to not do so would constitute moral injury. Not voicing support for the Ukrainian government and/or not denouncing Russia was commonly taken as an indication of a lack of support for victimized Ukrainian refugees and tacit support for aggression. Sanctioning Russia and appropriating property of Russian citizens and corporations ends up being a moral imperative that outweighs, at that point in time, the very high but distant practical costs to the sanctioners in higher energy and food costs. However, many supporters of Ukraine are now experiencing moral whiplash as they are confronted with the reality that Ukraine routinely uses its citizens as human shields, has bombed the largest nuclear power plant in Europe, risking a radiation disaster on a scale bigger than Chernobyl, and it becomes public knowledge in the West that as much as seventy percent of the military aid to Ukraine never reaches its intended use, instead being lost in a system of massive, ongoing institutionalized corruption. Blaming a much higher cost of living on Putin does not make those costs disappear, meaning moral outrage and sustaining moral injury can be irrelevant to dealing with real world challenges. Like post-traumatic stress disorder, moral injury can leave lasting emotional scars. Such moral injury occurs when there is cognitive dissonance between what our worldview says should or ought to happen and some other credible perspective that convinces us that something contradictory should or ought to happen. In a situation in which warfighters are not able to dissociate psychologically from the enemy, as was the case for this soldier, the likelihood of experiencing moral injury is higher. This is an important reason why experiential multi-perspectivalism and polycentrism in particular, are not taught or encouraged by many cultures and nation-states. It not only makes it more difficult to socialize and condition citizens to do the will of the state but threatens the cohesiveness of the state itself. Polycentrism, by getting us in touch with perspectives that are not experiencing either moral outrage or injury, can help us reframe events in ways that heal, balance, and transform rather than aggravate intrapsychic and international conflict. Taking a phenomenological approachTo further flesh out the difference between different varieties of experiential multi-perspectivalisms as well as from cognitive multi-perspectivalism, we have to understand what it means to take a phenomenological approach. This is because those who are practiced at cognitive multi-perspectivalisms, such as integralists, are generally sure they are experientially based in an integral and transpersonal way when both their worldview and their very identity are in fact largely derived from 1) prepersonal internalized familial and sociocultural scripting, cognitive maps they learned in school and from people like Wilber, and 2) mystical experiences. Those who want to account for the validity of their identity and worldview by appealing to mysticism and/or some teleological or spiritual principle, and still claim to perceive and act from an integral experiential multi-perspectivalism, have the burden of proof on their side. As Carl Sagan notably observed, “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof.” A reasonable and realistic suspicion is that such explanations serve as convenient justifications for maintaining a heavily scripted, psychologically geocentric or heliocentric status quo. As we have seen, some experiential cognitive multi-perspectivalisms are phenomenologically based and some are not. Ritter's experiential multi-perspectivalism is not phenomenologically-based, but it is not prepersonal either, while that of Integral Deep Listening (IDL) is phenomenologically-based. The difference is that Ritter's experiential multi-perspectivalism is based on lived experience - prolonged immersion in the worldview of Russia and Russians, which led to a deep appreciation and incorporation of that worldview into an expanded sense of self. It is also singular - immersion in one radically different outgroup perspective, so it is narrow - hardly a full-blown polycentrism. Phenomenologically-based experiential multi-perspectivalisms involve a methodology of repeatedly suspending waking identity and taking on various alternative perspectives, worldviews, and identities and then allowing them to describe themselves, their priorities and preferences, and to make recommendations. This is radically different from both cognitive multi-perspectivalism and non-PEMs. An example of a phenomenologically-based experiential multi-perspectivalism (PEM)There is much to recommend experiential multi-perspectivalisms, like Scott Ritter's experience, that involve immersion in worldviews and perspectives that challenge our own. There is nothing intrinsically incompatible between same and PEMs. In fact both are valuable and complement one another. PEMs, such as Integral Deep Listening (IDL), involve an interviewing methodology that experiential multi-perspectivalism does not require. The blind men, upon encountering the elephant, didn't become the elephant and take its perspective, much less answer questions from the perspective of the elephant. Palestinian supporters may be cognitively or experientially multi-perspectival, in that they have known Palestinians or gone to Palestine and experienced life from Palestinian perspectives, but they probably have not taken the perspective of a Palestinian and allowed that perspective to speak its truth through them. In order to develop his experiential multi-perspectivalism, Scott Ritter didn't do self-interviews in which he personified Russian perspectives, nor did he answer questions from those perspectives. Instead, he immersed himself in a radically different worldview from that which he had been scripted to accept and believe. With a PEM like IDL, three life issues of current significance serve as the starting point. The most pressing issue can be taken, personified, and interviewed. For example, if you have a stabbing pain in your back you can become the knife and answer questions from its perspective. Or, if you have a disturbing dream or nightmare you can become and interview one or more character in it. For example, dream monsters and villains threaten our worldview by challenging our sense of control, safety, security, status, and power, which still exists as part of our identity, even when we dream. If you hate Trump or Putin you can take their perspective and, to the best of your ability, answer the questions in the IDL interviewing protocol and see what happens. Of course, IDL does not claim you actually become the perspective of Trump or Putin, but neither does it claim that you merely access “shadow,” or self-aspects. This is because IDL views such perspectives as emerging potentials that are ontologically indeterminate: they cannot be reduced wholly and completely either to subjective components of some larger self, like the personal or collective unconscious, as “shadow” based psychological approaches do, nor can they be reduced to completely objective others, as shamanism, spiritualism, and mysticism do. PEMs cannot be reduced to “shadow” work, not only because interviewed others are not reduced to disowned or unconscious self-aspects, but because polycentrism cannot be reduced to the realm of self-development, which is the domain of shadow work of various sorts, whether Gestalt, parts work, or Wilber's 3-2-1 Shadow methodology. Interviewed perspectives are interested in their priorities, not yours and mine. They are interested in their expression, not the development of your self or Self. It is a psychologically geocentric projection and discount to simply view them as “parts” and deprive them of a degree of respect and autonomy that we reserve for ourselves. PEMs belong not only to the intrasocial, reality of the LL, interior collective quadrant, but also to the LR, exterior collective quadrant of relationship with objective others. This is not only because that is how they are experienced (particularly in dreams and mystical experiences) but because this is a claim they often make for themselves: that they are partially self-aspects and partially autonomous, thereby not limited to either the interior or exterior collective quadrants. We have seen how the “other,” that is, those entities, objects, experiences, and worldviews that are not incorporated into our identity and worldview, tend to be perceived either as threats, whether awake or dreaming, or as irrelevant. Perceived threats undercut our psychological geocentrism, regardless of our level of development. We never outgrow this challenge to our sense of self. It remains after years of meditation or demonstrated competency in various life fields. When we experience a threat, awake or dreaming, we typically attempt to re-establish and assert psychological geocentrism by repressing, ignoring, discounting, or controlling the experience. In contrast, PEMs attempt to give any alternative perspective, regardless of its reality status, a full and complete hearing. If it is threatening, all the better. Respect for any and all perspectives is fundamental, and the assumption is that the perspectives that are deemed most foreign, threatening, or inconsequential, have the most to offer us in terms of the expansion of our worldview and the thinning of our identity. The recommendations the perspective makes regarding the three life issues stated initially can be operationalized and tested in order to empirically evaluate their validity, the effectiveness and trustworthiness of this or that interviewed perspective, and the utility of the methodology itself. The structure of a polycentric interviewing processThe IDL interviewing protocol begins with the statement of three current life issues and then proceeds with questions designed to anchor identity in that of some alternative perspective. It then moves to questioning the perspective's interpretation of its function, to transformations possibly desired by the interviewed perspective, and an elaboration of core qualities of confidence, empathy, wisdom, acceptance, inner peace, and witnessing. Questioning of interviewed perspectives, called “emerging potentials,” ends with the elicitation of recommendations regarding the initial three life issues. Orientation questions addressed to the perspective include, “Where are you?” “What are you doing?” “What are your strengths, weaknesses?” Interpretation questions include, “What aspect of this person do you most closely personify?” “What aspect of YOU does this person most closely personify?” Transformation questions include, “Do you want to change? If you could, in any and every way, how would you change?” “How do you score in core qualities?” Recommendation questions include, “How would you deal with this person's three life issues?” “What life issues would you focus on if you were living their life?” The result, if one indeed refrains from interpretation and analysis, but instead commits themselves to spontaneously answering questions as the interviewed perspective, is sustained disidentification from psychological geocentrism for the duration of the interview accompanied by in-depth, sustained identification with whatever perspective has been chosen. Repetition of this interviewing process with multiple “others,” including personifications of life issues and dream characters, both with oneself and others, decentralizes identity, moving one from psychological geocentrism and/or heliocentrism toward polycentrism. This approach can be contrasted with the common advice to confront and challenge threats, be they school yard bullies, nightmare monsters and villains, abusive spouses, politicians, or adversarial nations. Such an approach can work in that it dispels the threat and bolsters confidence, but it does so at the expense of alienating and therefore not understanding or learning from the rejected other. Ingroups and outgroups become polarized and both social and intrapsychic conflict is exacerbated. The result is that when confrontation and confidence no longer appropriately size up an outgroup, personal and social collapse follows. Phenomenologically-based experiential multi-perspectivalisms can have results that are highly integrative. For example, people with varieties of chronic anxiety, such as panic disorder, phobia, or post-traumatic stress disorder often see symptoms diminish and, in some cases, vanish completely. Nightmares and repetitive dreams usually are eliminated. More important, however, is a generalized movement out of familial and socio-cultural scripting and groupthink toward an authentic identity that is much more in flow with life. Emerging potentials that point toward a stable and reliable life compass are accessed and amplified by the interviewing process. The self is thinned as it gives up control and shares reality with the identities and worldviews of multiple others. The result of this thinning is that there is less self to protect or defend and less self that needs to maintain control in order to maintain its identity. At the same time, rationality and common sense remain, which means that the ability to assess potential threats and respond appropriately is enhanced rather than diminished, which is what the self typically believes and fears. Taking a deeper dive into PEMsThe above example applies to IDL single character interviewing protocols, an example of one variety of PEM. While such interviews teach integral and transpersonal multi-perspectivalism and move one toward polycentrism, IDL is based on an approach that is even more effective and evidential. That is called “Dream Sociometry,” and is the methodology from which both individual character interviewing and the interviewing of personifications of life issues in IDL is derived.[6] Dream Sociometry interviews multiple characters from the same dream, life issue, historical or fictional event at the same time. The result is the objective depiction of multiple relatively autonomous and credible worldviews regarding the same issue at the same time. The consequence of creating a number of these is repeated confrontation with the illusoriness of both psychological geocentrism and heliocentrism. Repeated confrontation is necessary to break through habitual, persistent identification with psychological geocentrism, such is its adaptive value. To give you an idea of what the methodology looks like, here is an example of a Dream Sociomatrix:

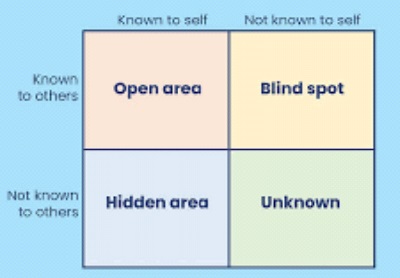

These numbers represent degrees of preference, like, like a lot, love, dislike, dislike a lot, hate, do not care, and unconditionally accepting represented by 1, 2, 3, -1, -2, -3, a blank, and an asterisk. In terms of the Johari Window, these preferences are not known to us and not known to objective others. They are “unknown unknowns.”

Johari Window

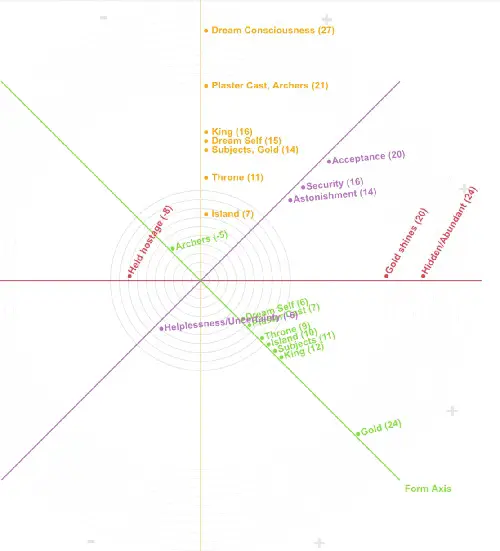

However, like the elephant's perception of its own experience, these preferences are known to intrasocial others of indeterminant ontology, denizens of the interior collective quadrant of our experience. You cannot access them by groping for different parts of the “elephant” or by projecting your interpretations onto them, which is what symbology does. The only way to access their identity and worldview is to become them and ask them to explain their preferences through commentaries called “elaborations,” which clarify the worldview of each interviewed perspective, indicating its similarities and differences from other interviewed perspectives. The result is that we are confronted with both interior polycentrism, that is, there is no one psychologically geocentric self that exists on an intrasocial level, and with a degree of autonomy of perspective that is unexpected, difficult to dismiss, enlightening, and creative, reflecting emerging potentials and pointing toward a hypothetical life compass. In order to evaluate and study the relationships among the various interviewed perspectives they can be depicted in a diagram called a Dream Sociogram.[7] These patterns of preference create varieties of collective relationship, and these are described in Understanding the Dream Sociogram.

Why collect all these preferences on all these imaginary elements? By doing so we are not only confronted by an amazing degree of unexpected autonomy, but by becoming them, we thin our investment in a unitary self that needs to stay in control and be protected. The result is less stress, anxiety, depression, and more peace of mind. Dream Sociometry accesses a wide variety of authentic, yet sometimes conflicting preferences, and this leads to a greater self-awareness as to what preferences reflect our societal conditioning and which ones reflect our emerging potentials. The absence of polycentrism leads us to publicly misrepresent our own private views, what scholars call preference falsification.[8] When articulating preferences we frequently tailor our choices to what appears socially acceptable. We convey preferences that differ from what we genuinely want. When preference falsification becomes widespread in a society it can result in collective illusions that hold back social progress, erode trust, and drive polarization, competition, and conflict. When we hide our discontent about a fashion, policy, or political regime it makes it harder for others to express discontent. Social pressure to have the “right” opinion is pervasive. In recent years, polls have consistently found that most Americans, across all demographics, feel they cannot share their honest opinions in public for fear of offending others or incurring retribution. For example, to question the policies and behavior of Israel can get one accused of anti-semitism and to question support for Ukraine can invite being labeled a “Putin bot,” or “useful idiot” of Russia. This trend is concerning because of the threat that it poses to individual freedoms, community flourishing, and democratic self-government. In falsifying our preferences, we hide the knowledge on which our true preferences rest. We thereby impoverish, distort, and corrupt knowledge in the public domain. We make it harder for others to become informed about the limits of existing policies, practices, and worldviews as well as the merits of their alternatives. Another consequence of preference falsification is thus widespread ignorance about the advantages of change. Preference falsification can create widespread public support for social options, such as war, sanctions, or corporate welfare that would be rejected decisively in a vote taken by secret ballot. Privately unpopular policies may be retained indefinitely as we reproduce conformist social pressures through our own preference falsification. Over long periods, preference falsification can dampen a community's capacity to want change by bringing about intellectual narrowness and ossification. The first of these consequences is driven by our need for social approval, the second by our reliance on each other for information. Another consequence is that we become identified with our false preferences and waste our lives defending them. We think they are authentic preferences when in fact they are driven by our desire to please others and our fear of what will happen if we do not. PEMs, by becoming and interviewing multiple alternative perspectives, unmasks and deconstructs preference falsification, persona, self, and Self. Why these concepts generally remain invisibleWhy do we not grow up learning what multi-perspectivalism is, the difference between cognitive and experiential multi-perspectivalisms, with the ability to distinguish between experiential multi-perspectivalisms and phenomenologically-based experiential multi-perspectivalisms? The short answer is that while prepersonal multi-perspectivalism is essential to development, it is largely invisible in childhood and adolescence. Higher forms, beyond cognitive multi-perspectivalism, do not further the agendas of either parents or society, nor do they support self development, as understood as the evolution toward integration of the self or Self. Multi-perspectivalism not only reduces the control of an executive self, but lessens the ability of authority figures to control individuals. A lack of self-control leads to ostracism and punishment. If we want to succeed, if we want others to support us, we had better learn self-control. Self-control is an obvious core value for parents and societies because it not only saves time but allows authorities to pose as nurturing benefactors because we do the limit-setting, internally. When expectations, norms, and laws are internalized, children and citizens enforce them themselves via self-control. Parents do not have to monitor the behavior of “socialized” children. Authorities do not have to be corralling us all the time. We go to work and pay our bills; we are cooperative consumers and workers. Socialized citizens are obedient and compliant, unlikely to rock the boat. If citizens learn to adapt to the expectations of society, government doesn't have to spend as much time enforcing laws. Polycentrism, whether through immersion in other cultures and lifestyles, taking psychedelics and having mystical experiences, threatens “Stay in control!” which is the categorical imperative of families and society. Polycentrism strikes at the roots of self-control by actively practicing its suspension. PEMs in particular undercut personal and societal control by teaching the value of giving it up, by providing a methodology for doing so, and creating experiences that demonstrate that the structured, intentional surrender of self-control is not necessarily a threat but can be a positive good. The paradoxical consequence is not a loss of self-control but the reduction of our habitual addiction to being in control. Those addicted to psychological geocentrism and those who are only familiar with cognitive multi-perspectivalism have difficulty differentiating the ability to respect and deeply understand alternative perspectives from the actual, experiential adoption of those perspectives. For example, they are incapable of understanding how Scott Ritter can respect Russian perspectives without becoming a supporter of authoritarianism and an enemy of the West and democracy. This is because they themselves have never learned experiential multi-perspectivalism and so the concept is foreign to them. It is inconceivable to them why they would find value in taking the perspective of a toilet brush or a velociraptor. Five reasons come to mind for the vast event horizon beyond which polycentrism lies. First, we have not been taught the distinction between cognitive and experiential multi-perspectivalisms. Second, we have no concept of the value of doing so. Third, we have not had life experiences that were not about accreting alternative perspectives onto our own worldview, expanding our psychological geocentrism or, at best, our heliocentrism. Fourth, giving up control has no apparent adaptive value and goes against years of scripting. While exceptions including partnering, work groups, and meditation exist, none of these involve polycentrism. Fifth, numerous adaptive, baked in cognitive biases view disidentification from identity and becoming other perspectives as leading to decompensation and depersonalization, in addition to loss of control and threatening identity, and therefore to be avoided, minimized, or fought. An example is the War on Drugs. Sixth, viewing polycentrism as “shadow work,” and therefore as about re-owning dissociated self-aspects in the interest of self-development, does not threaten the self or Self. The consequences of not learning to recognize and practice polycentrism can be severe. As mentioned above we are currently learning how our worldview has caused us to inflict sanctions on Russia that are having a devastating impact on our economies and standard of living. Those sanctions strengthened not only the Russian economy but turned Russia into the most stable and powerful autarky in the world, exactly the opposite of what was intended. How could so many compassionate and intelligent people be so short-sighted? How could the most successful worldview of the last five hundred years commit collective sociocide? We are not only killing our lifestyles; we are destroying hundreds of years of Western culture and dominance. The obsession for global control, that is, collective psychological geocentrism, has generated the unintentional demolition of that control. While that may indeed be a good thing, it doesn't have to be at the cost of so much human misery and risk to global life. ConclusionPolycentrism reduces our blind spots and the likelihood that we will make such significant personal and collective errors by consulting outgroup perspectives instead of simply assuming we understand them. We need to remember that our ignorance far outweighs what we know and demonstrate that awareness in authentic humility. Polycentrism integrates interior domains of self-consciousness, values, and worldview, on the one hand, and exterior relationships, particularly with the disowned other, on the other hand. It does so whether that “other” is objectively real or subjectively experienced or believed, as in a dream, near death or mystical experience or mental fantasy. The resulting congruency between inner and outer, microcosm and macrocosm, provides a foundation for credibility and authenticity. These in turn are necessary to justify trust and a sense of empathy, without which intimacy in relationships, whether individual, corporate, or international, cannot be sustained. Without a methodology to access and evaluate the credibility of polycentric multiple perspectives, they will remain not only invisible to us but inconsequential and irrelevant. We will continue to be controlled by psychological geocentrism, with its imbalanced focus on self-development, and heliocentrism, with its grandiose focus on idealism, consciousness, intent, and self-actualization. With this overview of varieties of multi-perspectivalism, we can now look at three major problems confronting humanity. These problems are 1) the neglect of foundational relational exchanges, 2) a lack of triangulation, and 3) a lack of ethical congruence. All three keep both individuals and societies stuck in their socio-cultural evolution. We can then explore how PEMs provide important and necessary solutions to these foundational problems.

NOTES

|