|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Dr. Joseph Dillard is a psychotherapist with over forty year's clinical experience treating individual, couple, and family issues. Dr. Dillard also has extensive experience with pain management and meditation training. The creator of Integral Deep Listening (IDL), Dr. Dillard is the author of over ten books on IDL, dreaming, nightmares, and meditation. He lives in Berlin, Germany. See: integraldeeplistening.com and his YouTube channel. Dr. Joseph Dillard is a psychotherapist with over forty year's clinical experience treating individual, couple, and family issues. Dr. Dillard also has extensive experience with pain management and meditation training. The creator of Integral Deep Listening (IDL), Dr. Dillard is the author of over ten books on IDL, dreaming, nightmares, and meditation. He lives in Berlin, Germany. See: integraldeeplistening.com and his YouTube channel.

SEE MORE ESSAYS WRITTEN BY JOSEPH DILLARD

Characteristics of Our Emerging WorldviewPart 2: The Indian WorldviewJoseph Dillard

The Indian worldview doesn't challenge the Western economic order but rather co-exists with it, addressing largely higher relational exchanges.

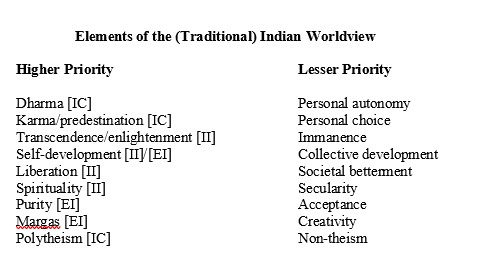

In the first essay of this series we have compared Western and Global South worldviews within the context of the integral/metamodern worldview, associating various priorities with different holonic quadrants along with the inference of neglected or rejected worldview priorities. Now we will do much the same with important elements of the traditional Indian worldview, focusing on the compatibilities of Hinduism and Buddhism instead of their many and significant differences.[1] We will then consider compatibilities of the Indian worldview with both Western and Integral/metamodern worldviews, and conjecture regarding how the Indian worldview is likely to fare within the rapidly evolving clash of multiple worldviews. As in the first essay in this series, I have provided my subjective estimation of which of the four holonic quadrants of Wilber's AQAL a priority is most closely aligned with, with the implication that the opposite quadrant is most excluded, neglected, or ignored. These designations are as follows: Interior Individual [II], Interior Collective [IC], Exterior Individual [EI], and Exterior Collective [EC]).

Why has the Indian worldview been so easily subsumed within the Western worldview? Priorities of the Indian worldview largely focus on higher relational exchanges, such as transpersonal development and access to subtle, causal, and non-dual states of consciousness. Pursuing your personal enlightenment will eliminate both your personal as well as societal suffering. What these priorities tell us is that the Indian worldview not only does not challenge, in ways that matter, the Western worldview, but on the whole is compatible with it. Those expositors and believers in the Western worldview can pursue its economic, colonialistic, military, informational, social, and cultural ends on Wall St., the City of London, and Frankfurt, in the Global South, through the Military Industrial Complex, media, political, and current norms and still meditate, become Hindus or Buddhists, believe in Dharma, karma, and reincarnation, and pursue spirituality and transcendence. Indian worldview priorities, like dharma and karma, are generally presented as the consequence of personal choices and responsibilities, not collective ones. The Indian worldview doesn't challenge the Western economic order but rather co-exists with it, addressing largely higher relational exchanges. The Western worldview is not threatened or affected one way or another by such interests or priorities. Economics focuses on lower relational exchanges; food, security, safety, labor, wealth, and status. Functionally there is no challenge or contradiction. Exploitation, war, injustice, and amorality can continue largely unhindered when one embraces the Indian worldview. There is a great deal of evidence to support this conclusion. The Edgar Cayce psychic readings provide an excellent example of how Vedantist Hinduism can be merged not only with Christianity and a Western worldview, but holism and “new age” interests and priorities. The Baghavad Gita, perhaps the central text of Hinduism, supports “holy war.”[2] Buddhism retreats from conflict into a Sangha/monastery-centered reality, thereby providing no threat to Western “business as usual.” Tibetan Buddhism, perhaps the pinnacle of Buddhist philosophy and spirituality, existed in a purely feudal society, in which some 95% of the population were landless, powerless, impoverished, uneducated serfs and indentured slaves, controlled and managed by the Buddhist Sangha.[3] Traditional and contemporary Buddhist economic systems either do not challenge Western economics or incorporate it. The philosophy and spiritual pursuits of both Hinduism and Buddhism have been assimilated into Western culture and thought without disrupting the dominance of the Western worldview. This is largely because while they largely focus on transcendence and higher order relational exchanges, the Western worldview largely focuses on safety, security, food, status, and power - lower relational exchanges. Those lower relational exchanges are not only developmentally prior, but provide the foundation for pursuit of higher exchanges. For example, it is difficult to meditate or pursue enlightenment when you have no time because you must work to provide for your family. Therefore, the acquisition and maintenance of lower relational exchanges is where most individuals and societies necessarily focus to raise families and maintain social cohesion.

Dharma/Personal Autonomy

Dharma is divine law. Liberation (samadhi), enlightenment, and personal fulfillment occur when one lives in accordance with it. “In the early Vedas and other ancient Hindu texts, dharma referred to the cosmic law that created the ordered universe from chaos. Later, it was applied to other contexts, including human behaviors and ways of living that prevent society, family and nature from descending into chaos. This included the concepts of duty, rights, religion and morally appropriate behavior, and so dharma came to be understood as a means to preserve and maintain righteousness.

As a value underpinning human purpose, dharma has its natural home in the interior collective quadrant, implying that the most likely deficiency is in the exterior individual quadrant - the difference between professed intention and actual behavior.

Karma-Predestination/Personal Choice

Because we choose where, when, and how we are to reincarnate, the fulfillment of dharma comes from accepting and making the most of those conditions. It is “the force generated by a person's actions held in Hinduism and Buddhism to perpetuate transmigration and in its ethical consequences to determine the nature of the person's next existence.” Merriam-webster Karma is a powerful tool for social cohesion. If I believe I am a Sudra because I “chose” to be a Sudra, and my path to enlightenment depends on me doing a good job as a Sudra, I am not going to blame secular or religious authorities for unjust or abusive life circumstances for myself or my family. The law of karma generates a passive, compliant society and social order in which individuals take upon themselves maximum responsibility and have minimal expectations of responsibility or accountability for others, and social elites in particular. The oppositional quadrant is exterior individual behavior, and it is best when it aligns itself with the priorities of the interior collective values of Dharma. The result is that individual autonomy and personal choice are subordinated to collective and institutionalized authority.

Transcendence-Enlightenment/Immanence

Enlightenment is transcendence of the suffering that is innate to life and incarnation. In Hinduism, you want to outgrow the need to reincarnate. In Buddhism, you either want the same or to become a Buddha or Bodhisattva and incarnate for the benefit of humanity. “The doctrine or theory of immanence holds that the divine encompasses or is manifested in the material world. It is held by some philosophical and metaphysical theories of divine presence. Immanence is usually applied in monotheistic, pantheistic, pandeistic, or panentheistic faiths to suggest that the spiritual world permeates the mundane. It is often contrasted with theories of transcendence, in which the divine is seen to be outside the material world.” Wikipedia. The opposite or de-emphasized quadrant for the Indian worldview is the exterior collective, most clearly conceptualized as outgroups. For Hinduism, which is marvelously synchretic, those outgroups are secularity and impurity rather than other religions or belief systems. For Buddhism, those outgroups are those individuals, pursuits, thoughts, and desires that lead one away from the Eightfold Noble Path.

Self-development/Collective development

Self-development as the evolution of consciousness prioritizes the interior individual quadrant while self-development as personal behavior prioritizes the exterior individual. In both cases the perspectives, interests, and development of both interior, microcosmic collectives and exterior, macrocosmic ones, is a lesser priority. Self-development is the natural, normal priority of the first third of life. It is also conceived of as the purpose of life, as in Maslow's self-actualization and spiritual enlightenment. It is the fundamental theme of both western psychology and Indian religion. In contrast, collective development subordinates self-development to the needs of the group. This is the priority in both hunter-gatherer and agrarian/Bronze Age societies in which group survival is dependent on individual conformity. Collective development as a priority again becomes primary in polycentrism, when identity becomes multi-perspectival, and socially, when society becomes so interdependent that disturbances in others we do not know can affect us in life-disruptive ways.

Liberation/Societal Betterment

In the Indian worldview, everyone is responsible for their own enlightenment and liberation. Societal betterment can upset the status quo, which exists as it “should be,” as a manifestation of dharma/karma.

Spirituality/Secularity

In the Indian worldview, living a spiritual life is better than living a secular life. The idea is to spiritualize secular life rather than to accept secular life on its own terms. This is another example of affirmation of the interior quadrants over the exterior individual and collective ones.

Purity/Acceptance

While accepting that the impure nature of incarnation is necessary, in the Indian worldview one should always work to separate oneself from its defiling and corrupting nature. This is an interior collective assumption that is not shared by plants and animals, that do not draw distinctions between either spirituality and secularity or purity and acceptance of impurity. This is because plants and animals are subjectively enmeshed in their experience and have not objectified the interior quadrants of consciousness and value. Experience and life is exterior; there is not yet a subjective “I” in experience. As humans continue to evolve, they can reintegrate, without losing hard-earned subjectivity or objectivity.

Margas/Creativity

Margas are injunctive yogas, or behavioral prescriptions that lead to enlightenment. The life yogas (karma, Jnana, bhakti) are laid out by scripture and gurus. Our job is to follow those instructions. Creativity is a lower priority than following traditional sacred injunctions. Creativity can challenge the divine order and disrupt society. This is not to imply that Indians are less creative than other people, but rather point to how we can exist in socio-cultural contexts that emphasize or de-emphasize the value of creativity in general, or limit it to specific areas.

Polytheism/Non-Theism

While Buddhism is neither theistic, atheistic, or agnostic, functionally and practically, Bodhisattvas and Buddhas are worshipped via prayer, mandalas, yantras, and other observances. Monotheisms and polytheisms generally experience non-theisms as atheism, when what may exist is agnosticism or no “ism” at all. Therefore, what is embraced is a religious/spiritual ideology in the interior collective while the most excluded quadrant is likely to be the exterior individual lived as life without ideology. The outward or public face of Indian religion in the interior individual quadrant is one of serenity and devotion. The interior or subjective face of Indian religion is one of struggle against the non-spiritual and impure.

Conclusion

None of this is to deny the brilliance, importance, and utility of the Indian worldview or its amazing contributions to civilization, culture, or personal development. I, along with many others, have gained immeasurably through studying Hindu and Buddhist worldviews and incorporating important elements of them into my life. Nevertheless, because its strengths largely lie in interior quadrant priorities, the Indian worldview is largely impotent or neutral where it interfaces with the Western worldview. This implies that the Indian worldview is likely to share the fate of the Western worldview, and that is to be marginalized and subsumed in an emerging broader synthesis. This is because the Indian worldview, like that of the West, fails to adequately support the lower, foundational relational exchanges upon which personal and societal development and cohesion depends, in healthy ways that stand the tests of time. Instead, the Indian worldview, like that of the West, protects the interests of ingroups at the expense of outgroups. Both worldviews contain significant imbalances that are difficult to correct without undermining the worldview itself. For example, both fail to hold social institutions accountable for human welfare, or the lack of it, and this failure is significant and fundamental.[4] To rectify that deficit would be to radically alter fundamental components of both worldviews. In the next essay in this series I will address important priorities of the Chinese worldview and consider some of the ways its rise challenges and disrupts other worldviews.

NOTES

"Prior to 1959, 95% of the Tibetan population were slaves."

|