|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

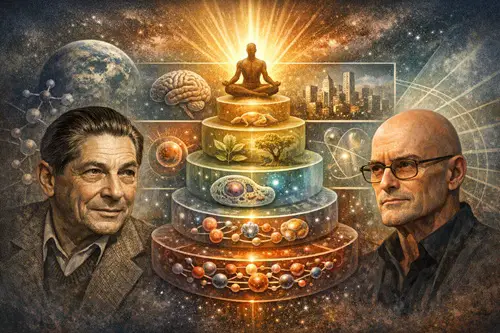

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020). Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020).

Check out my other conversations with ChatGPT Ken Wilber and the Appropriation of Arthur Koestler's Holon ConceptFrank Visser / ChatGPT

Few conceptual borrowings have been as central to Ken Wilber's Integral Theory as the notion of the holon. Originally introduced by Arthur Koestler in The Ghost in the Machine (1967), the holon was a biological and systems-theoretical insight into the nested structure of complex organisms. Wilber, however, transforms it into the ontological backbone of a grand evolutionary metaphysics. The shift from Koestler's modest heuristic to Wilber's architectonic principle is philosophically revealing—and controversial. This essay examines (1) Koestler's original formulation, (2) Wilber's reinterpretation, and (3) the conceptual and metaphysical implications of this move. 1. Koestler's Original HolonKoestler coined the term holon to solve a problem in systems theory and biology: entities in living systems are neither reducible parts nor autonomous wholes. A cell is a whole relative to its organelles, yet a part relative to a tissue. Likewise, a word is a whole relative to letters but part of a sentence. The holon captures this dual aspect: • Self-assertive tendencies (preserving autonomy) • Integrative tendencies (functioning within larger wholes) Koestler's interest was empirical and structural. He sought a non-reductionist model of hierarchical organization without invoking mysticism. His �holarchy� described nested systems—organs within organisms, organisms within ecologies—without implying teleological inevitability or spiritual ascent. Importantly, Koestler's hierarchies were not metaphysical ladders. They were descriptive features of complex adaptive systems. 2. Wilber's Expansion into OntologyWilber adopts the holon as the foundational unit of reality. In works such as Sex, Ecology, Spirituality, he declares: �The universe is composed of holons.� Everything—atoms, cells, minds, cultures—is simultaneously a whole and a part. However, Wilber introduces several decisive expansions: A. From Description to MetaphysicsWhere Koestler described biological organization, Wilber universalizes the concept. Holons become ontological primitives: reality is holarchical. This move elevates a systems metaphor into a metaphysical doctrine. B. Evolutionary DirectionalityWilber integrates holons into a developmental narrative. Holarchies become evolutionary sequences, allegedly driven by increasing depth and consciousness. Atoms ? molecules ? cells ? organisms ? minds ? soul ? spirit. Here the holon concept is pressed into service for a progressive cosmology. Hierarchy becomes �growth,� and depth becomes �greater interiority.� C. Interior/Exterior QuadrantsWilber's AQAL model (All Quadrants, All Levels) adds a further layer. Every holon possesses: • An interior (subjective/intentional dimension) • An exterior (behavioral/structural dimension) • An individual pole • A collective pole Koestler never posited intrinsic interiors at every level of reality. Wilber's move effectively embeds proto-consciousness into the fabric of the cosmos—an implicit panexperientialism. 3. Conceptual StrengthsTo be fair, Wilber's use of the holon has several virtues: • Anti-reductionism: It resists flatland materialism by emphasizing nested complexity. • Cross-disciplinary coherence: The holon functions as a bridging concept across biology, psychology, and sociology. • Developmental integration: It offers a structural grammar for stage theories of growth. For readers disillusioned with reductionist science, the holon offers an intuitively satisfying middle ground between atomism and mystical monism. 4. Philosophical ProblemsHowever, Wilber's expansion introduces significant tensions. A. Reification of MetaphorKoestler's holon was a heuristic construct. Wilber treats it as an ontological fact. The transition from explanatory model to metaphysical axiom is not argued but assumed. One may accept nested complexity without concluding that reality is intrinsically structured as a spiritual ascent. B. Smuggling in TeleologyWilber interprets holarchies as inherently progressive. Yet in biological evolution, hierarchy does not equal improvement. Bacteria remain extraordinarily successful life forms. Complexity is not destiny. The holon, under Wilber's pen, becomes a carrier of Eros—a quasi-mystical drive toward higher consciousness. This goes far beyond Koestler. C. Hierarchy and Value InflationWilber distinguishes between �growth hierarchies� and �dominator hierarchies.� Nevertheless, once depth equals greater consciousness, hierarchy becomes value-laden. Critics argue that this invites subtle spiritual elitism: higher holons possess greater reality. Koestler's concept did not entail such normative stratification. D. Panpsychic DriftBy attributing interiors to all holons, Wilber edges toward panpsychism or panexperientialism. This move is not entailed by systems theory. It represents a metaphysical augmentation layered onto Koestler's structural insight. 5. The Deeper PatternWilber's use of Koestler reflects a broader methodological pattern: • Identify a respected scientific or systems-theoretical concept. • Generalize it beyond its empirical scope. • Integrate it into a comprehensive spiritual cosmology. The holon becomes the scaffolding for a universe animated by Spirit-in-action. The key question is whether this represents legitimate philosophical extrapolation—or conceptual overreach. 6. ConclusionArthur Koestler introduced the holon to clarify the paradoxical nature of parts and wholes in complex systems. Ken Wilber transforms it into the ontological building block of a spiritually evolving cosmos. The difference is profound: • Koestler: descriptive systems theory. • Wilber: metaphysical integralism. Whether one sees Wilber's move as visionary synthesis or unwarranted inflation depends largely on one's tolerance for metaphysical ambition. What is clear, however, is that the holon in Integral Theory is no longer Koestler's modest structural insight. It has become the keystone of an evolutionary spiritual narrative. And that transformation deserves critical scrutiny.

Comment Form is loading comments...

|