|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

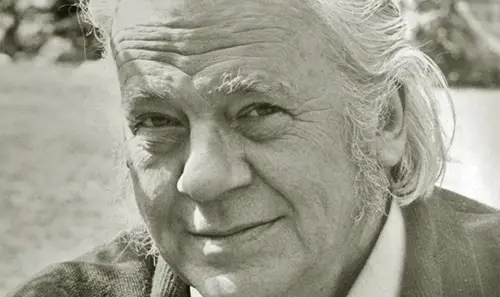

Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020). Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020).

Check out my other conversations with ChatGPT E.F. Schumacher and the Four QuadrantsFrom Epistemic Distinction to Ontological SystemFrank Visser / ChatGPT

Ken Wilber's Four Quadrants model is widely regarded as the conceptual cornerstone of Integral Theory. It is frequently presented as a novel synthesis capable of integrating science, psychology, culture, and spirituality within a single coherent framework. Yet the basic structural intuition behind the quadrants—crossing inner and outer perspectives with individual and collective reference points—did not originate with Wilber. A strikingly precise precursor appears in E.F. Schumacher's A Guide for the Perplexed (1977), where a fourfold epistemological framework anticipates the quadrant model almost point for point. Recognizing this lineage is not merely a matter of intellectual attribution. It illuminates a crucial difference in philosophical temperament: Schumacher's fourfold distinction is an exercise in epistemic humility, while Wilber's quadrants evolve into an ontological totalization. Understanding this divergence helps clarify both the appeal and the limitations of Integral Theory. Schumacher's Four Domains of KnowledgeIn A Guide for the Perplexed, Schumacher devotes four central chapters to what he considers the basic domains of human knowledge. Rather than organizing these domains by subject matter (physics, biology, psychology, theology), Schumacher organizes them by mode of access—that is, how knowledge is obtained and what kind of certainty it can legitimately claim. The four domains are: • One's own invisible inner experiences • The invisible inner experience of others • One's own visible outer apparatus • The visible outer apparatus of others These distinctions are deceptively simple. Schumacher is not proposing a metaphysical theory of reality, but a framework for avoiding systematic confusion in how we claim to know things. The decisive axes are clear: inner vs. outer and self vs. other. Any act of knowing, Schumacher argues, must fall within one of these domains, and each domain has its own evidential standards and limitations. Mapping Schumacher to the Four Quadrants When set beside Wilber's quadrant model, the correspondence is unmistakable: • Upper-Left (UL): One's own invisible inner experiences • Lower-Left (LL): The invisible inner experience of others • Upper-Right (UR): One's own visible outer apparatus • Lower-Right (LR): The visible outer apparatus of others Wilber's later language of first-, second-, and third-person perspectives does little more than redescribe Schumacher's epistemic distinctions in contemporary philosophical idiom. What Wilber calls phenomenology, cultural interpretation, behavioral science, and systems theory are already present in Schumacher's account—without diagrams, jargon, or metaphysical inflation. Crucially, Schumacher's framework is strictly epistemological. It concerns what can be known directly, what must be inferred, and what kinds of error arise when methods are misapplied. It does not claim that all four domains are equally fundamental features of reality itself.

Schumacher's Epistemic RestraintSchumacher repeatedly warns against category mistakes. Inner experiences cannot be measured like physical objects; outer apparatus cannot be understood through introspection. Knowledge of other minds is necessarily indirect and interpretive. Social systems cannot be reduced to personal intentions, nor can personal experience be dissolved into systems. Yet Schumacher never claims that these distinctions solve philosophical problems such as consciousness, meaning, or purpose. On the contrary, they clarify why such problems are difficult and why simplistic answers are suspect. His fourfold framework functions as a discipline of thought, not as a theory of everything. This restraint is deliberate. Schumacher is acutely aware that modern science's success in the outer domains has tempted thinkers to overextend its methods into domains where they do not belong. His fourfold scheme is meant to block such overreach—not to replace it with a new metaphysical system. Wilber's Ontological TurnWilber adopts a nearly identical structural distinction but transforms it in a decisive way. The Four Quadrants are no longer merely domains of knowledge; they become dimensions of being. Every entity, Wilber claims, is a �holon� possessing interior and exterior aspects, individual and collective dimensions, all of which arise simultaneously. This move converts Schumacher's epistemological caution into an ontological assertion. What Schumacher treated as limits of knowing, Wilber treats as the architecture of reality itself. The quadrants thus become not just a guide to inquiry but a metaphysical map—one that purports to show how consciousness, matter, culture, and systems fit together in an evolutionary process driven by Spirit. The cost of this move is significant. Once the quadrants are ontologized, they no longer merely warn against reductionism; they institutionalize it by cordoning off domains in advance. Explanatory questions—such as how consciousness relates to brain processes—are deflected by asserting that these belong to different quadrants and are therefore irreducible. Why Schumacher Matters More Than EverSeen in light of Schumacher's original formulation, the Four Quadrants appear less revolutionary than often claimed. Their intuitive appeal derives in large part from the fact that they rest on commonsense epistemic distinctions that philosophers and scientists have long recognized. Schumacher's version has the advantage of modesty. It acknowledges pluralism without promising synthesis, integration without totalization. It helps us see why disagreements persist—because different domains require different kinds of evidence—without pretending to dissolve those disagreements through a higher-order schema. Wilber's quadrants, by contrast, risk becoming a conceptual comfort blanket: everything has its place, all perspectives are honored, and conflict is reinterpreted as partial vision rather than genuine theoretical disagreement. Prior Recognition of the Schumacher�Wilber ParallelIt should be noted that the close structural correspondence between Schumacher's fourfold epistemology and Wilber's Four Quadrants is not a retrospective reconstruction. It was already identified and discussed in Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY Press, 2003), where I pointed out that Schumacher's distinction between inner and outer, self and other, anticipates the quadrant model in virtually all essential respects. At the time, this observation served to question the frequent presentation of the quadrants as a conceptual breakthrough, suggesting instead that Wilber systematized and ontologized an existing epistemological framework. This continuity does not diminish the pedagogical appeal of the quadrants, but it does place them within a longer intellectual lineage and reinforces the view that their principal function is classificatory rather than explanatory. Recognizing Schumacher's influence—explicit or implicit—helps clarify both the strengths of the quadrant model and the philosophical costs of expanding an epistemic guide into a comprehensive metaphysical system. Conclusion: From Guide to SystemE.F. Schumacher titled his book A Guide for the Perplexed for good reason. His fourfold epistemology does not promise mastery, only orientation. It accepts that reality resists unification under a single explanatory framework and that wisdom often consists in knowing the limits of one's methods. Ken Wilber's Four Quadrants can be understood as an ambitious extension of this guide—but also as a departure from its spirit. By transforming epistemic distinctions into ontological claims, Wilber turns a map of knowing into a map of being. Whether that move represents a genuine advance or a philosophical overreach remains an open—and pressing—question. What is clear is that the conceptual roots of the quadrants lie not in Integral Theory itself, but in an earlier, quieter tradition of philosophical restraint—one that Schumacher articulated with remarkable clarity long before the quadrants were given their now-familiar name.

Comment Form is loading comments...

|