|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020). Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020).

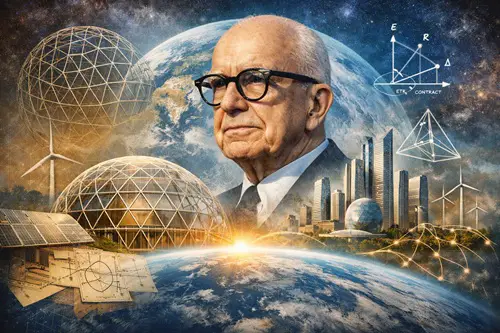

Check out my other conversations with ChatGPT Buckminster FullerLegacy, Relevance, and the Limits of Visionary ThinkingFrank Visser / ChatGPT

Few twentieth-century figures occupy as strange and ambiguous a position as Richard Buckminster Fuller (1895-1983). To admirers, he was a polymath visionary who anticipated ecological thinking, systems theory, and global responsibility decades before they became fashionable. To critics, he was a technocratic utopian whose sweeping generalizations routinely outran both empirical evidence and practical feasibility. The truth lies between these extremes. Fuller's enduring significance does not rest in the correctness of his specific proposals, but in the conceptual tools he introduced for thinking about design, resources, and humanity's planetary predicament. 1. Fuller's Core Vision: Design Science and “Spaceship Earth”At the heart of Fuller's worldview was a deceptively simple claim: humanity's problems are not fundamentally political or moral, but design failures. He argued that Earth should be understood as a closed, finite system—famously dubbed “Spaceship Earth”—with no instruction manual and no external resupply. Within this system, waste, poverty, and conflict were not inevitable features of human nature but consequences of inefficient and outdated technological arrangements. This framing was radical in the mid-20th century. Long before environmentalism became mainstream, Fuller emphasized: • planetary limits, • resource efficiency, • energy optimization, • and global interdependence. His insistence that “there is enough for everyone if we design intelligently” anticipated later debates about sustainability, circular economies, and ecological footprints. Importantly, Fuller did not advocate austerity or anti-technology primitivism. On the contrary, he believed advanced technology was the only viable route to universal prosperity. 2. The Geodesic Dome: Symbol, Not SolutionFuller's most iconic contribution, the geodesic dome, illustrates both his brilliance and his limitations. Structurally elegant, mathematically grounded, and materially efficient, domes demonstrated that radically lightweight structures could enclose large volumes using minimal resources. They became emblems of countercultural experimentation in the 1960s and 1970s and were deployed in military, exhibition, and emergency contexts. Yet geodesic domes never fulfilled Fuller's dream of mass adoption for housing. Practical issues—insulation, acoustics, maintenance, zoning laws, and human preferences—proved stubborn. This gap between theoretical efficiency and lived usability recurs throughout Fuller's career. His ideas often worked best as provocations rather than as turnkey solutions. Still, the dome's deeper legacy lies elsewhere: it reshaped how architects and engineers think about structure, load distribution, and material efficiency, influencing later developments in tensegrity, parametric design, and computational architecture. 3. Synergetics and the Problem of Private LanguageFuller's most ambitious intellectual project, Synergetics, aimed to replace conventional Euclidean geometry with a universal, energy-based description of nature. He believed this new geometry captured deeper truths about how systems self-organize across scales—from atoms to galaxies. While intriguing, Synergetics remains largely idiosyncratic. Its terminology is dense, its notation unconventional, and its claims rarely integrated into mainstream mathematics or physics. Critics argue that Fuller mistook metaphorical resonance for explanatory power, creating a private conceptual universe that resisted external validation. Nevertheless, Synergetics prefigured later emphases on systems thinking, emergence, and non-linear dynamics, even if its formal apparatus never gained traction. Fuller sensed, correctly, that reductionist models were insufficient for understanding complex wholes—though his proposed alternative was more visionary than rigorous. 4. Ethical Optimism and the Technocratic TemptationOne of Fuller's most distinctive traits was his unwavering optimism. He believed humanity was in the midst of a “design revolution” that would make war, poverty, and hierarchy obsolete. Technology, properly applied, would enable what he called “ephemeralization”—doing more and more with less and less. This optimism was ethically inspiring but politically naïve. Fuller tended to underplay: • power asymmetries, • institutional inertia, • cultural resistance, • and the social embeddedness of technology. Design does not occur in a vacuum; it is shaped by economic incentives, political interests, and ideological commitments. Technological abundance alone does not guarantee equitable distribution or wise use. Here, Fuller's legacy intersects with later critiques of technosolutionism. Yet his optimism was not escapist. Unlike mystical or metaphysical utopians, Fuller grounded his hope in engineering realities, energy flows, and material constraints. He was a rationalist visionary, not a spiritual one. 5. Contemporary Relevance: Why Fuller Still MattersIn the 21st century, Fuller's relevance has arguably increased rather than diminished. Climate change, resource depletion, and global inequality now force precisely the planetary-scale thinking he advocated. Concepts such as: • life-cycle analysis, • systems engineering, • sustainable design, • and global governance of commons all resonate strongly with Fuller's work. Moreover, his insistence on anticipatory design—solving problems before they manifest catastrophically—aligns with contemporary approaches to resilience, climate adaptation, and long-term risk management. Where Fuller remains most valuable is not in his specific forecasts, many of which were wrong or overly optimistic, but in his refusal to accept piecemeal thinking in a tightly coupled world. 6. Conclusion: A Catalyst, Not a BlueprintBuckminster Fuller should be remembered neither as a prophet nor as a crank, but as a catalyst. He expanded the imaginative horizon of what design, engineering, and responsibility could mean on a planetary scale. His work reminds us that how we frame problems often determines whether solutions are even conceivable. At the same time, Fuller's legacy also serves as a cautionary tale: visionary synthesis must remain accountable to empirical reality, social complexity, and human behavior. Systems thinking can illuminate—but it can also seduce. In an age increasingly defined by global constraints and technological power, Fuller's central question remains urgent: Can humanity learn to design itself into a viable future—before circumstances design it out of one? That question, more than any dome or diagram, is Buckminster Fuller's lasting contribution.

Comment Form is loading comments...

|