|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

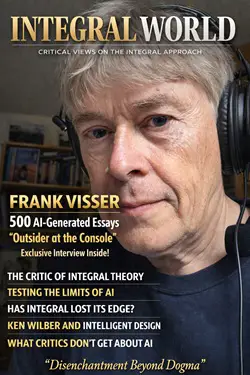

Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020). Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020).

Check out my other conversations with ChatGPT

“Integral Theory includes everything except the possibility that its metaphysical core is mistaken. I occupy that excluded space. From there, the view is clearer, the claims more modest, and the standards higher.”

'Outsider at the Console'Frank Visser on 500 AI-Generated Essays, Integral Theory, and the Discipline of DisenchantmentFrank Visser / ChatGPTFor two decades, Integral World has been a singular outpost of critical engagement with Ken Wilber's Integral Theory. Now, its founder, Frank Visser, has crossed an unusual threshold: the publication of 500 AI-generated articles—openly labeled, minimally edited, and publicly archived. Is this an act of provocation, pedagogy, self-indulgence, or intellectual experimentation? We sat down with Visser to discuss authorship, authority, AI, and what remains of “integral” thinking after the metaphysics have been stripped away. Before the Bot: The First 250 EssaysInterviewer: Frank, before the AI phase that everyone is now talking about, you had already written roughly 250 essays by hand for Integral World. Why start the interview there? Frank Visser: Because without those essays, the AI phase makes no sense.

Integral World did not begin as an experiment in automation. It began as a long, patient engagement with Ken Wilber's claim to have articulated a Theory of Everything. I took that claim seriously—seriously enough to test it across philosophy, science, religion, and cultural theory, essay by essay, over many years. Those 250 hand-written pieces were not reactions or hit jobs. They were attempts at internal critique: “If Wilber is right, then X should follow. Does it?” Interviewer: How would you characterize those early essays in retrospect? Visser: They were acts of gradual disenchantment. At first, I assumed Wilber's system merely needed clarification or tightening. Over time, a pattern emerged: whenever empirical science aligned with Wilber, it was embraced as confirmation; whenever it diverged—especially on evolution, cosmology, or consciousness—it was reinterpreted as incomplete, reductionist, or confined to the “Lower-Right quadrant.” That asymmetry is fatal to any genuine Theory of Everything. A TOE cannot selectively defer to science only when convenient. Interviewer: Was there a particular breaking point? Visser: Yes—Wilber's treatment of evolution. The more closely I examined his use of Eros, Spirit-in-Action, or “self-transcending drives,” the clearer it became that these were not neutral metaphors but metaphysical commitments. Purpose was being read into evolution and then shielded from criticism by redefining it as trans-empirical. At that point, the resemblance to Intelligent Design—albeit in a mystically sophisticated form—was impossible to ignore. That realization fundamentally reshaped my work. Interviewer: So the AI phase did not replace human authorship—it followed it? Visser: Exactly. The AI did not discover the problems in Wilber's TOE. Those problems were documented, argued, and refined across hundreds of human-written essays. What AI changed was the tempo and the visibility of critique. It allowed me to test Wilber's claims more rapidly, more systematically, and without the emotional friction that inevitably accompanies long-standing intellectual disputes. In a sense, the first 250 essays built the map. The next 500 stress-tested it. Interviewer: And how do you see the relationship between the two phases now? Visser: The hand-written essays established credibility and depth. The AI essays expose scale and pattern. Together, they make one continuous argument: that Wilber's Theory of Everything overreaches precisely where it claims the most authority—by spiritualizing domains that demand empirical restraint. The medium changed, but the critical standard did not. CONVERSATIONS WITH THE BOTInterviewer: Frank, 500 AI-generated articles is not a trivial number. Why do this at all? Frank Visser: Because it was possible—and because it revealed something. From the outset, this was not about efficiency or outsourcing thinking. It was about exposure: exposing how ideas behave when you remove the author's aura, exposing how readers respond when the voice is explicitly non-human, and exposing—perhaps most importantly—how Integral Theory itself fares when subjected to relentless, unemotional analysis. I never pretended these were “human essays.” I called them Conversations with the Bot. That framing matters. It tells the reader: this is an experiment, not a performance. Interviewer: Critics say publishing AI output at this scale undermines intellectual seriousness. Visser: Only if you believe seriousness is a function of handwriting. That assumption has always amused me. What unsettles people is not that the material is shallow—often it isn't—but that the traditional signals of authorship are missing. No struggle is visible. No reputation is at stake. And yet the arguments land, the structures hold, and the citations are often better than what passes for discourse in integral circles. The discomfort says more about credentialism than about content. Interviewer: You were once deeply embedded in the Integral world—you even wrote the first academic monograph on Wilber. How does this AI phase relate to that earlier commitment? Visser: It's a continuation, not a detour. My break with Wilber was not emotional; it was epistemic. Over time, I realized that Integral Theory systematically immunizes itself against falsification. When science agrees, it is celebrated. When science disagrees, it is reclassified as “partial,” “flatland,” or “gross-realm only.” AI turns out to be a perfect tool for testing such systems, because it has no spiritual investments. It does not revere Wilber. It does not fear his followers. It simply tracks coherence, evidence, and argumentative integrity. Integral Theory fares poorly under those conditions. Interviewer: You've described Wilber's work as harboring a kind of “closet creationism.” That's a strong charge. Visser: It is strong—and accurate. Wilber's language about Eros, Spirit-in-Action, or evolutionary drive functions exactly like Intelligent Design rhetoric, only with better prose and more footnotes. Purpose is smuggled into evolution, then retroactively declared metaphorical when challenged. What AI helps demonstrate is how repetitive and circular this move is. Once you strip away the rhetorical flourishes, the structure becomes obvious: • Evolution trends upward. • Upward trends imply direction. • Direction implies Spirit. • Spirit is beyond empirical critique. That is not integration. It is insulation. Interviewer: Some of your readers feel alienated by the sheer volume of AI material. Visser: Yes—and I understand that reaction. Integral World was once a carefully curated archive of essays. It has now become something closer to a laboratory notebook. Not everyone wants to watch experiments unfold in real time. But I've never chased readership metrics. Integral World exists because I want to understand these issues clearly. If others benefit, excellent. If they don't, that is not a failure. There's a freedom in that stance that many intellectuals never allow themselves. Interviewer: Still, why publish the AI output publicly instead of keeping it private? Visser: Transparency. AI is already being used everywhere—quietly, selectively, often dishonestly. By publishing raw conversations, I remove the mystique. Readers can judge for themselves: Is this insightful? Is it derivative? Is it flawed? And they can compare it to human writing that is often protected by reputation rather than rigor. In that sense, the project is pedagogical. It teaches discernment. Interviewer: Do you see AI as a collaborator, a tool, or something else? Visser: A cognitive instrument—closer to a telescope than a co-author. It extends reach. It accelerates comparison. It forces precision. But it does not care. That lack of care is a feature, not a bug, especially when dealing with spiritually loaded claims. I decide what to ask. I decide what to publish. Responsibility remains human. Interviewer: Some Integral defenders accuse you of bitterness. Visser: That accusation has been my constant companion for twenty years. What they call bitterness is usually disenchantment. When you invest decades in a framework and then realize it overreaches—especially in its engagement with science—the result is not anger but clarity. AI sharpens that clarity. It has no patience for spiritual alpinism or mystical exceptionalism. It treats those as hypotheses—and finds them wanting. Interviewer: Looking back, do you think Integral Theory could have evolved differently? Visser: Yes. It could have accepted limits. A genuinely integral approach would have said: spirituality has subjective value; science governs empirical claims; and the boundary between them matters. Wilber refused that humility. He wanted a Theory of Everything—and paid the epistemic price. Ironically, AI now performs a more genuinely integrative function by cross-checking domains without privileging any of them metaphysically. Interviewer: After 500 AI-generated articles, what remains of the project? Visser: What remains is the same thing that was always there: a commitment to intellectual honesty. The AI phase may pass. Another fascination will take its place. That has always been my rhythm—deep immersion, followed by release. But Integral World will continue to stand for something simple and unfashionable: that no idea, however spiritually dressed, is exempt from critique. Interviewer: Final question. What would you say to readers who still prefer “human-written” essays? Visser: I sympathize. Humans tell better stories. But ideas are not validated by their authorship. They are validated by their coherence, their evidentiary grounding, and their willingness to face reality without metaphysical escape hatches. If AI helps make that visible—even uncomfortably—then these 500 articles have already done their work. After the MetaphysicsInterviewer: Frank, many integralists would say that your current naturalistic worldview reflects a kind of regression—an abandonment of higher developmental perspectives in favor of what they would call “flatland” realism. How do you respond to that charge? Visser: I see it as a category mistake—and a revealing one. Integral Theory equates metaphysical expansion with developmental advancement. If you affirm subtle realms, cosmic purpose, or Spirit-in-Action, you are deemed “higher.” If you reject those claims on evidential grounds, you are classified as “earlier,” “partial,” or “limited.” But intellectual maturity is not measured by how much metaphysics one can entertain. It is measured by one's willingness to say no where the evidence ends. Interviewer: They might argue that naturalism forecloses whole dimensions of reality before they can even be explored. Visser: Only if one confuses experience with ontology. I have never denied the richness of inner life, altered states, or spiritual experience. What I deny is the automatic upgrade of such experiences into claims about the structure of the cosmos. Naturalism draws a boundary, not a blindfold. It says: subjective meaning is real; explanatory inflation is optional—and often unjustified. Integral Theory erases that boundary and then calls the erasure “integration.” Interviewer: Still, within Integral discourse, rejecting Spirit, Eros, or teleology is often interpreted as developmental arrest. Does that characterization concern you? Visser: Not anymore. For years, I took such judgments personally, as if I had failed to “grow into” something. Eventually I realized they function rhetorically, not diagnostically. Labeling critics as underdeveloped is a way to avoid answering them. A worldview that cannot tolerate principled dissent without psychologizing it is not advanced—it is fragile. Interviewer: So you do not experience your naturalism as a loss? Visser: On the contrary, it was a gain. Leaving behind metaphysical superstructures—Theosophical, Integral, or otherwise—allowed me to appreciate the world as it is, not as it is promised to become. Complexity without cosmic intention is still astonishing. Meaning without metaphysical guarantees is still meaningful. Naturalism, for me, was not a narrowing of vision but a clearing of it. Interviewer: Final question. If Integral Theory claims to include everything, where does that leave someone like you? Visser: Outside—and quite comfortably so. Integral Theory includes everything except the possibility that its metaphysical core is mistaken. I occupy that excluded space. From there, the view is clearer, the claims more modest, and the standards higher. If that position is deemed “underdeveloped,” I can live with the judgment. I would rather be limited by evidence than liberated by assertion. Frank Visser is the founder of Integral World and author of Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY Press). He lives contentedly as a well-informed outsider, still asking inconvenient questions—now with silicon assistance.

Comment Form is loading comments...

|