|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020). Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020).

Check out my other conversations with ChatGPT Mapping the Philosophy of MindFrom Spectrum to 3D ModelFrank Visser / ChatGPT

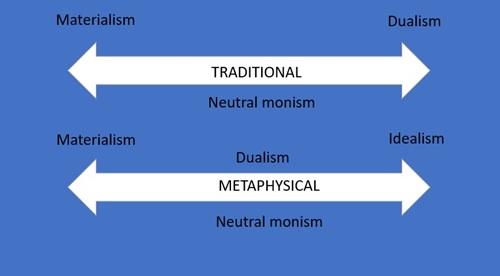

Philosophy of mind has always been haunted by the problem of structure: how best to map the competing views of mind and matter, subject and object, consciousness and the physical world. The field is notoriously pluralistic—materialists, dualists, idealists, panpsychists, neutral monists, and functionalists coexist uneasily, each claiming to solve the “hard problem” or to dissolve it. But beneath this cacophony lies a meta-question: how should we visualize the landscape of positions? Two major approaches suggest themselves. The first is to see the field as a spectrum between materialism and dualism, with variants such as emergentism, property dualism, and epiphenomenalism occupying middle ground. The second is to define it as a spectrum between materialism and idealism, with dualism and neutral monism as intermediate or balancing positions. Each model highlights a different tension in the debate—and each has its merits and distortions. 1. The Traditional Spectrum: From Matter to MindThe first, and historically dominant, way of structuring philosophy of mind is the materialism-dualism spectrum. At one pole lies materialism (or physicalism): the conviction that everything real is physical, and that mind is either reducible to or emergent from matter. From the mechanistic monism of Hobbes to contemporary functionalism and cognitive neuroscience, this stance seeks to explain consciousness without invoking any extra ontological ingredients. At the opposite pole stands substance dualism, most famously associated with Descartes, which posits two fundamentally distinct kinds of substance—mental and physical. On this view, mind and matter are ontologically disjoint yet interact. Between these poles lie the so-called property dualisms (David Chalmers, for example), which accept one physical world but insist that consciousness is a fundamental feature that cannot be reduced to physical properties. This mapping highlights the explanatory challenge of integrating mind into a physical universe: how can subjective experience arise from objective matter? The advantage of this framing is that it directly reflects the historical lineage of the mind-body problem and resonates with the methodological naturalism of modern science. The downside is that it leaves no space for idealism—for views that deny the independent existence of matter altogether. 2. The Metaphysical Spectrum: From Matter to Mind, or Mind to MatterThe alternative mapping, which is more metaphysically inclusive, places materialism and idealism at opposite poles. Here, the axis is not between monism and dualism, but between two kinds of monism—one privileging matter, the other privileging mind. In this model:

This framing allows for a more symmetrical ontology. It situates dualism as a midpoint rather than an endpoint, and acknowledges that both materialism and idealism are mirror images of each other—each claiming one pole of a deeper continuum. In this schema, the philosophical problem is not merely how mind and matter interact, but which is ontologically prior—or whether they share a common ground. 3. Comparing the Two Models

The first model is empirical and methodological: it speaks to neuroscience, cognitive science, and naturalistic philosophy. The second is ontological and metaphysical: it asks what kind of “stuff” reality is ultimately made of. Both schemata are legitimate, but they serve different purposes. The first clarifies debates within the natural sciences; the second situates them within the wider metaphysical history that includes Spinoza, Schopenhauer, and contemporary panpsychists. 4. Beyond the Spectrum: Plurality or Integration?There is, however, a deeper question: is the field best understood as a spectrum at all? Spectra imply a single underlying dimension—a linear transition from one metaphysical commitment to another. But the history of philosophy of mind may be better visualized as a map with multiple axes:

Such a multidimensional mapping reveals that “dualism” and “neutral monism” are not merely halfway houses, but distinct configurations of these dimensions. It also helps to show that panpsychism, process philosophy, and information-based metaphysics are not intermediate compromises but alternative reorganizations of the entire problem. 5. Dualism and Neutral Monism in a Three-Dimensional SpaceWhen we plot philosophies of mind not along a single line but in a three-dimensional conceptual space, we can disentangle their hidden assumptions. Let's define three axes:

This multidimensional mapping helps us to see why dualism and neutral monism are not mere “halfway houses” between materialism and idealism, but distinct structural types of worldview. (1) Ontological Priority: Substance vs. Neutral GroundDualism asserts two fundamental kinds of being: mental and physical. It is therefore bi-substantial. Ontological priority is split—neither mind nor matter reduces to the other. They coexist as coequal realms. Neutral Monism asserts that both mind and matter are manifestations of a deeper, neutral reality. This neutral “stuff” (Russell's “neutral elements,” Spinoza's “substance,” James's “pure experience”) is neither mental nor physical until it is viewed under one or the other aspect. Ontological priority here belongs to the neutral base, not to either pole. On this axis, dualism represents ontological parity, whereas neutral monism represents ontological unification at a deeper level. (2) Epistemic Orientation: Objectivity vs. SubjectivityDualism tends to polarize epistemic access: physical things are known through third-person observation, mental things through first-person introspection. Cartesian dualism institutionalized this split, giving rise to the epistemic gap between science and consciousness studies. Neutral Monism, in contrast, seeks an epistemic reconciliation: if mind and matter are aspects of the same neutral “stuff,” then first- and third-person knowledge are complementary modes of accessing a single reality. Russell, for instance, argued that physics gives us the structure of the world (relations), while consciousness gives us its intrinsic character (qualitative feel). Thus, dualism preserves the epistemic split it posits, while neutral monism dissolves it into two perspectives on one underlying reality. (3) Causal Symmetry: One-Way, Two-Way, or Non-Causal CorrelationDualism faces the notorious interaction problem. If mind and matter are separate substances, how can they causally affect one another? Interactionist dualists (Descartes, Eccles) posit two-way causation. Parallelists (Leibniz) deny direct interaction but maintain a pre-established harmony. Epiphenomenalists grant one-way causation—from matter to mind—but deny any reverse influence. Dualism therefore lives along a vertical axis of causal asymmetry, oscillating between interaction and impotence. Neutral Monism, by contrast, typically avoids causal talk altogether. If both mind and matter are derivative aspects of a neutral base, their correspondence is not causal but correlative—two expressions of the same underlying process. In modern terms, this looks less like “causation between realms” and more like emergence within a unified ontology. For example, in panprotopsychist or process models, consciousness and physicality co-arise as complementary manifestations of one informational or experiential substrate. Hence, while dualism struggles with causal linkage across ontological divides, neutral monism dissolves the divide, replacing causation with aspectual co-expression.

6. The Philosophical ImplicationsIn this multidimensional view, dualism appears as a structural disjunction: two realities, two ways of knowing, two causal chains that never quite meet. It captures the intuitive difference between inner and outer experience, but at the cost of coherence. Neutral monism, on the other hand, is a structural reconciliation: it preserves the experiential dualities while rooting them in a single neutral source. It attempts to satisfy the physicalist's demand for unity without denying the phenomenologist's insistence on the reality of experience. Yet this reconciliation comes at a price: the “neutral base” remains ontologically mysterious. What is this substance that is neither mental nor physical? Pure experience? Information? Process? Neutral monism avoids dualism's clash, but risks dissolving into vagueness unless it specifies what the neutral “stuff” is. 7. A Dynamic Metaphysical MapIf we imagine these three axes graphically, dualism sits near the corner of ontological separation, epistemic division, and causal asymmetry. Neutral monism shifts toward the center—ontological unity, epistemic complementarity, and causal correlation. Materialism occupies one extreme (ontological matter-priority, objective epistemology, one-way causation from matter to mind), while idealism occupies its mirror (ontological mind-priority, subjective epistemology, one-way causation from mind to matter). Dualism and neutral monism are thus not midpoints on a line but nodes in a multidimensional landscape, each resolving and reintroducing different tensions. Dualism dramatizes the divide between inner and outer; neutral monism seeks to naturalize it into a single explanatory fabric. 8. Conclusion: From Spectrum to SpaceThe philosophy of mind resists any single-axis simplification. A one-dimensional spectrum—whether between materialism and dualism, or materialism and idealism—captures part of the story but flattens the complexity of our conceptual terrain. Once we introduce the three dimensions of ontological priority, epistemic orientation, and causal symmetry, the field unfolds into a genuine space of possibilities, not a mere line of opposition. Within this expanded topology:

When positioned here, Wilber and Kastrup illustrate two distinct ways of transcending reductionism: Kastrup does so by collapsing the entire field into the pole of mind-first idealism, where matter is merely appearance. Wilber attempts a dynamic synthesis, approaching neutral monism through a spiritualized evolutionary process in which matter and mind are different expressions of Spirit's unfolding. Thus, the two-spectrum model of the philosophy of mind gives way to a three-dimensional landscape—a cognitive map that situates every position not just along a line, but within a volume of metaphysical possibility. In this 3D view, philosophy of mind ceases to be a tug-of-war between matter and spirit, and becomes a more subtle geometry of perspectives: a living space where ontological, epistemic, and causal commitments intersect to form the architecture of our understanding of consciousness itself.

Comment Form is loading comments...

|