|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020). Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020).

Check out my other conversations with ChatGPT Freinacht and Wilber on the Spirit of EvolutionFaith or Foresight?Frank Visser / ChatGPT

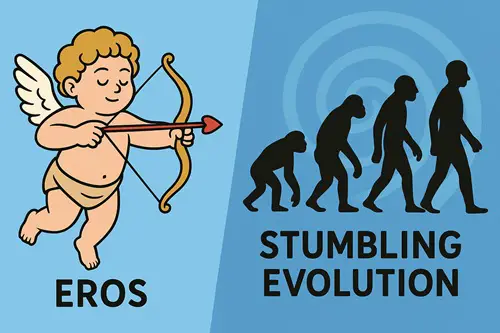

When Daniel Görtz, writing under the name Hanzi Freinacht, rejects the idea of a “spirit of evolution,” he does more than distance himself from Teilhard de Chardin or New Age optimism. He draws a bright, critical line between post-metaphysical metamodernism and Ken Wilber's integral spiritualism.[1] “Evolution doesn't 'look ahead' and push itself towards a goal or end or 'singularity'. The intellectual laziness of such thinking has always abhorred me.” — Hanzi Freinacht For Wilber, evolution is Spirit's own adventure of self-discovery; for Freinacht, such claims are precisely where philosophy slips into prophetic arrogance. The universe, he insists, does not march toward unity—it stumbles forward, blind to its own future. Between these two visions of evolution lies a profound debate about knowledge, humility, and the limits of meaning. 1. Wilber's Eros: Spirit-in-ActionFrom Sex, Ecology, Spirituality (1995) onward, Wilber's system rests on a single metaphysical intuition: that evolution has direction. Across cosmos, life, and culture, he perceives a pattern of transcendence and inclusion—matter giving rise to life, life to mind, and mind to Spirit. Wilber interprets this unfolding as evidence of an inner Eros, a divine impulse woven into the fabric of reality. “Evolution,” he famously wrote, “is Spirit-in-action.” Just as gravity pulls objects together in space, Eros pulls existence toward increasing complexity, consciousness, and compassion. For Wilber, to deny this inner drive is to render the cosmos meaningless—a mechanical drift without depth. He regards spiritual evolution not as sentimental wishful thinking but as the only coherent interpretation of the universe's self-organizing creativity. This metaphysical confidence, however, comes at a cost. It demands that we trust intuition over agnosticism, and teleology over contingency. In doing so, Wilber transforms evolution from a process of adaptive happenstance into a sacred narrative—a myth that doubles as metaphysics. 2. Freinacht's Agnosticism: Evolution as Stumbling ForwardFreinacht's metamodern project begins by dismantling precisely that kind of cosmic certainty. He is not content to trade scientific reductionism for spiritual grandiosity. His tone is unmistakably allergic to prophecy: “The moment we start believing in such an entity [a spirit of evolution], and that we can somehow intuitively or intellectually tap into this force and serve its purpose, we become tunnel-visioned 'true believers'... prophets, speaking the word of God. An unforgivable vanity.” Freinacht's universe is not unfolding toward an Omega Point but wandering through possibility space. Evolution, both biological and cultural, is improvisational and error-prone—a “stumbling forward” rather than a guided ascent. To imagine a “force that propels history,” he argues, is to mistake our yearning for meaning as metaphysical insight. The future, on his account, cannot be known or served in advance. The task is not to divine its direction but to listen—to sense emerging needs, contradictions, and potentialities without pretending to foresee their culmination. This is a philosophy of epistemic modesty, not cosmic design. 3. Teleology and Its DiscontentsThe conflict between Wilber and Freinacht is not merely stylistic. It reveals two incompatible stances toward the problem of teleology—the question of whether nature and history have intrinsic goals. Wilber's Eros restores a sense of direction to an otherwise indifferent universe. It promises coherence, continuity, and ultimate meaning. Yet in doing so, it revives a theological logic long discredited by science: that complexity implies intention, that order implies purpose. Freinacht refuses this inference. He accepts evolution's creativity but denies it foresight. The universe can generate novelty without aiming at transcendence. To call this “intellectual laziness,” as he does, is to accuse teleologists of using mystery as explanation: replacing the unknown with “Spirit” rather than investigating how self-organization, chance, and feedback loops suffice. Where Wilber sees Eros, Freinacht sees emergence; where Wilber sees divine ascent, Freinacht sees historical improvisation. 4. The Ethics of UnknowingAt the heart of Freinacht's stance lies an ethical warning. Belief in a “force propelling history” easily mutates into moral arrogance—the conviction that one knows what the universe wants and therefore what others should do. “We implicitly take ourselves to be prophets,” he writes, “speaking the word of God.” Wilber's notion of “Spirit-in-action” has inspired generations to see themselves as participants in a cosmic awakening. Yet this same inspiration can foster ideological blindness: if evolution must move toward unity, then dissent and divergence can only be pathologies, regressions, or “lower stages.” Freinacht's agnosticism safeguards against that temptation. By declaring the future unknowable, he preserves the pluralism and unpredictability of history. His metaphor of “listening to the melodies of the future” evokes not command but attunement—an ethics of responsiveness rather than revelation. 5. Two Kinds of FaithBoth thinkers, in the end, ask us to have faith—but their faiths point in opposite directions. Wilber's faith is metaphysical: that evolution's arc bends toward Spirit, that the cosmos is a self-realizing divine drama. It is an act of trust in the ultimate coherence of existence. Freinacht's faith is existential: that meaning can still be created in a world without ultimate guarantees. It is a trust without metaphysical insurance. Wilber spiritualizes evolution; Freinacht humanizes it. Wilber calls us to participate in Spirit's unfolding; Freinacht calls us to stay awake to history's accidents. 6. Conclusion: From Eros to EmergenceFreinacht's rejection of the “spirit of evolution” represents a decisive shift from cosmic faith to cognitive humility. He does not deny that development occurs—biological, psychological, cultural—but insists it lacks intrinsic purpose. To project divine intention into that process is, for him, a form of philosophical vanity. Wilber's system, by contrast, remains rooted in the metaphysical imagination of the 20th century—a grand synthesis of science and Spirit meant to redeem modernity's disenchantment. Yet the cost of such synthesis is certainty, and the price of certainty is blindness to surprise. If Wilber's integral theory portrays evolution as Spirit's awakening to itself, Freinacht's metamodernism portrays it as the universe awakening to its own ignorance—a cosmos forever improvising, forever off-balance, forever stumbling forward. Perhaps both are right in their own registers: Wilber in his longing for coherence, Freinacht in his devotion to complexity. But between faith in Eros and the humility of emergence, the intellectual winds of the 21st century clearly blow toward Freinacht's side. NOTES[1] Hanzi Freinacht, Facebook post, November 3, 2025.

Comment Form is loading comments...

|