|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020). Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020).

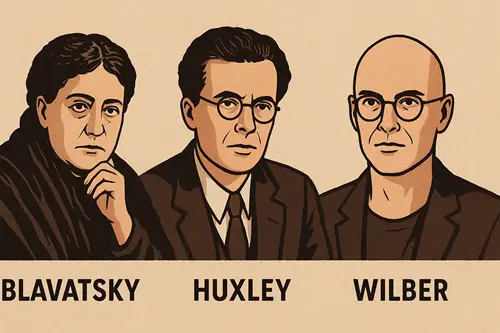

Check out my other conversations with ChatGPT The Phases of PerennialismFrom Theosophy to Aldous Huxley to Ken WilberFrank Visser / ChatGPT

Introduction: What Is Perennialism?Perennialism is the idea that all the world's religions, philosophies, and mystical traditions point to a single, universal spiritual truth. This “philosophia perennis,” a term popularized by Gottfried Leibniz in the 18th century but reaching back to Renaissance thinkers like Marsilio Ficino, has resurfaced repeatedly in modern religious and intellectual history. In the modern period, perennialism moved through several identifiable phases: the esoteric synthesis of Theosophy, the literary popularization of Aldous Huxley, and the developmental synthesis of Ken Wilber's Integral Theory. Each phase broadened and reframed the perennialist idea according to the cultural moment. 1. Theosophy and the Esoteric PhaseRoots and ContextFounded in 1875 by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, Henry Steel Olcott, and William Q. Judge, the Theosophical Society represents one of the earliest systematic attempts to articulate perennialism in a modern, global context. Blavatsky drew upon a wide array of sources—Hinduism, Buddhism, Gnosticism, Hermeticism—claiming to restore an ancient wisdom tradition that undergirded all the world's religions. Key ConceptsEsoteric Evolution: Theosophy proposed a cosmic evolution of consciousness, including rounds, globes, and root races—mythic cycles intended to show a grand spiritual unity across time. Hidden Masters: Blavatsky claimed to be in contact with “Mahatmas” or spiritual adepts in Tibet, who transmitted esoteric teachings to her. Universal Brotherhood: The Society's first objective explicitly sought to unite humanity across racial, religious, and national divisions. Perennialist FramingBlavatsky's The Secret Doctrine (1888) presented a grand synthesis: all religions were “branches” of a primordial tradition, and the deepest truths were reserved for the initiates. This esoteric perennialism was both anti-materialist (opposing the rising prestige of science) and anti-dogmatic (rejecting the exclusivity of Christianity). LimitationsTheosophy's perennialism was steeped in metaphysical claims and speculative cosmology. Its syncretism sometimes led to distortions of Eastern traditions, and its occult claims invited skepticism. Nonetheless, it marked the first large-scale global dissemination of perennialist ideas, especially in the West. 2. Aldous Huxley and the Literary PhaseA New Cultural MomentBy the mid-20th century, the spiritual landscape had changed. The horrors of World War II, the decline of European colonialism, and the rise of comparative religion studies created new openings for universalist perspectives. Aldous Huxley (1894-1963), an English novelist and essayist, emerged as perennialism's most articulate popularizer in this period. The Perennial Philosophy (1945)Huxley's landmark book, The Perennial Philosophy, distilled a lifetime of reading in the world's religious classics—Christian mystics, Vedantists, Sufis, and Mahayana Buddhists. He presented their teachings as variations on a single core insight: the unity of the Divine Ground and the possibility of realizing it through contemplative practice and ethical self-transcendence. Key ThemesMystical Core: Mysticism, not dogma, was the heart of religion. Psychological Interpretation: Huxley emphasized inner experience, self-discipline, and the dissolution of the ego as universal paths to realization. Ethical Corollary: The perennial philosophy, for Huxley, implied compassion and humility as natural expressions of spiritual realization. Modernizing the MessageUnlike Theosophy's occult narrative, Huxley's perennialism was rationalist, literary, and accessible. It fit the mid-century hunger for a spirituality beyond institutional religion but still anchored in tradition. LimitationsHuxley's book, while elegant, was largely an anthology with commentary. It did not resolve tensions between different traditions (e.g., personal theism vs. nondualism), nor did it address modern science beyond a cursory critique of materialism. Still, it provided a credible, secular-friendly entry point to perennialism. 3. Ken Wilber and the Integral PhaseContext: Late 20th-Century ConvergenceBy the 1970s and 1980s, perennialism encountered a world saturated with psychology, systems theory, and evolutionary thinking. Ken Wilber (b. 1949) emerged as a synthesizer who attempted to integrate the perennial philosophy with modern science, developmental psychology, and a historical sense of cultural evolution. The Spectrum of Consciousness (1977) and BeyondWilber's early work explicitly adopted a perennialist framework: all schools of psychology and spirituality represented stages along a single spectrum of consciousness. Over time, he developed “Integral Theory,” a meta-framework with four quadrants (interior/exterior, individual/collective) and multiple developmental lines and levels. Key ContributionsDevelopmental Lens: Unlike Huxley, Wilber placed the perennial philosophy in an evolutionary context—humans evolve from prepersonal to personal to transpersonal stages. Structural Differentiation: Wilber argued that modernity's differentiation of science, morals, and art was necessary and valuable, even if ultimately to be integrated at a higher stage. Reframing Religion: Traditional religious myths were reinterpreted as “pre-rational” but potentially leading to “trans-rational” mysticism. Perennialism RecastWilber shifted perennialism from a static, timeless truth to a dynamic developmental process. The mystical core remained but was now embedded in an integral model of human growth and cultural evolution. This appealed to spiritually inclined moderns who also valued science, psychology, and progress. LimitationsCritics argue that Wilber's model sometimes over-systematizes, turning perennial insights into rigid stage theories. Others note that his perennialism still privileges nondual mysticism (often Vedanta or Mahayana) as the apex of human development, echoing earlier biases. Yet his work marks the most ambitious modern attempt to reconcile perennial philosophy with contemporary knowledge. 4. Comparing the Phases

5. Beyond Wilber: Prospects for a Fourth PhasePerennialism continues to evolve. Current debates focus on decolonizing spirituality, acknowledging cultural specificity, and integrating scientific research on consciousness without metaphysical overreach. A “fourth phase” might involve: Pluralistic Perennialism: Recognizing multiple ultimate realities or types of mystical experience, rather than one monolithic “core.” Empirical Spirituality: Combining neuroscientific research, cross-cultural psychology, and first-person reports to map states of consciousness. Ethical and Ecological Grounding: Addressing global crises by linking perennial insights to planetary ethics. This would represent a move from timeless metaphysics to contextual and evidence-based universalism. Conclusion: The Perennial QuestFrom Theosophy's bold occult synthesis to Huxley's elegant literary rendering to Wilber's developmental meta-theory, perennialism has adapted to each historical moment's needs and sensibilities. Its enduring appeal lies in its promise of unity amidst diversity—a sense that beneath the cacophony of religious doctrines lies a single, transforming insight into the nature of reality and self. Yet each phase also reveals perennialism's vulnerabilities: cultural appropriation, speculative metaphysics, or over-systematization. The challenge for future thinkers will be to preserve perennialism's universal aspiration while remaining humble about its claims, attentive to cultural differences, and open to empirical validation. Perennialism, in short, is not a static doctrine but a living project—an ongoing attempt to articulate a universal wisdom adequate to our evolving understanding of the world. Comment Form is loading comments...

|