|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020). Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020).

Check out my other conversations with ChatGPT

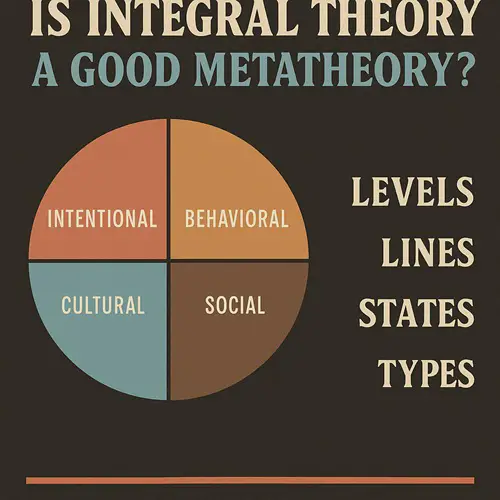

Is Integral Theory a Good Metatheory?How to Decide—and How It Compares to AlternativesFrank Visser / ChatGPT

In recent decades, Integral Theory (IT), chiefly developed by Ken Wilber, has emerged as one of the most comprehensive attempts at constructing a metatheory—a theory about how to relate and synthesize other theories. Its ambition is undeniable: to integrate the truths of science, spirituality, psychology, philosophy, and culture into a unified framework. But ambition alone doesn't make a metatheory effective. This article explores how we might evaluate whether Integral Theory qualifies as a good metatheory and compares it with several alternative integrative models. What Makes a Metatheory “Good”?A metatheory is a second-order framework: it doesn't offer a singular theory about the world but a way to coordinate many theories. This involves identifying deeper patterns, classifying domains of knowledge, and ideally showing how disparate perspectives can be reconciled or aligned. To assess the value of any metatheory—including IT—we can consider the following criteria: Coherence – Are its internal concepts logically consistent and clearly defined? Comprehensiveness – Does it include a wide range of perspectives, fields, and domains? Parsimony – Does it avoid unnecessary complexity or speculative metaphysics? Explanatory Power – Does it help resolve theoretical conflicts or illuminate hidden connections? Empirical Accountability – Can it interface meaningfully with empirical science and evidence? Pragmatic Utility – Is it useful in application—e.g., in research, therapy, education, or social policy? Critical Openness – Is it self-correcting and responsive to criticism? With this evaluative rubric in hand, we can examine Integral Theory more closely. The Promise of Integral TheoryWilber's IT is built around the AQAL model—“All Quadrants, All Levels, All Lines, All States, All Types.” This system attempts to map reality across four fundamental perspectives (subjective, objective, intersubjective, interobjective), layered with models of developmental stages (e.g., moral, cognitive, spiritual), typologies (e.g., Jungian personality types), and states of consciousness (e.g., waking, dreaming, mystical). Strengths of IT include: Comprehensiveness: IT excels in breadth. Few metatheories attempt to coordinate neuroscience, systems theory, Vajrayana Buddhism, depth psychology, and cultural anthropology. IT does. Coherence (internally): The AQAL model is systematic. By insisting that all valid perspectives be accounted for—“you can't get rid of any”—Wilber ensures a formal structure that appears consistent within its own terms. Pragmatic Utility: The AQAL model has been used in psychotherapy, organizational development, education, and coaching. It offers a navigational map for self-understanding and leadership training. Inclusiveness: Wilber's idea of “transcend and include” attempts to retain the partial truths of various worldviews—from mythic religion to modern science to postmodern relativism—within a developmental trajectory. The Problems of Integral TheoryDespite its strengths, IT is not without significant flaws. When judged by the full criteria for a robust metatheory, several limitations emerge: 1. Empirical Ambiguity Wilber frequently blends empirically grounded developmental models (like those of Piaget, Loevinger, or Graves) with speculative or mystical elements—such as the claim that the cosmos is driven by a spiritual Eros or that involution precedes evolution. These metaphysical commitments are not only untestable but often conflict with naturalistic understandings of evolution and cosmology. 2. Metaphysical Inflation What begins as a framework for integrating human knowledge often drifts into metaphysical overreach. Claims about subtle bodies, ascending planes, or reincarnating holons are presented with an air of authority, yet they derive largely from esoteric traditions rather than from critical or empirical validation. 3. Critical Defensiveness While IT claims inclusivity, Wilber's engagement with critics has often been dismissive or hostile. In his infamous Wyatt Earp blog posts, critics were accused of being stuck in “mean green meme” postmodernism or of shadow projection. Rather than engaging in dialectical debate, Wilber often interprets dissent as evidence of lower developmental altitude. 4. Developmental Overreach The linear stage-model assumptions in IT tend to flatten the complexities of cultural and historical phenomena. While developmental models may apply in some psychological domains, extending them to explain entire civilizations or philosophical paradigms risks distortion. This creates a grand narrative that borders on Hegelian idealism more than grounded analysis. 5. Questionable Coherence Across Domains While IT is coherent within its own system, it often imposes that system upon diverse domains in ways that strain credibility. Mapping spiritual states onto levels of social complexity or equating mystical experience with evolutionary advancement assumes cross-domain equivalences that may not hold. How IT Compares to Alternative MetatheoriesTo understand the unique strengths and weaknesses of Integral Theory, it's instructive to compare it with other notable metatheoretical frameworks that attempt integration without resorting to mystical teleology. Critical Realism (Roy Bhaskar, Margaret Archer) Focus: Ontological stratification (physical, biological, social), emergence, and causal depth. Strengths: Philosophically rigorous and compatible with empirical science; provides tools to understand social structure and human agency. Weaknesses: Less psychologically rich than IT; more academic. Comparison: Critical Realism is less visionary but more grounded than IT, especially in its rejection of spiritual metaphysics. General Systems Theory / Cybernetics (von Bertalanffy, Bateson) Focus: Feedback loops, complex systems, autopoiesis, and ecological interdependence. Strengths: Strong in modeling dynamic processes across biology, ecology, and sociology. Weaknesses: Often abstract; can overlook interior experience. Comparison: IT attempts to “add” consciousness and meaning to systems thinking, but often does so via mysticism rather than rigorous interface. Integral Pluralism / Complexity Thinking (Edgar Morin) Focus: Embracing uncertainty, dialogical reasoning, and transdisciplinarity. Strengths: Reflexive and self-critical; avoids grand unities. Weaknesses: Less prescriptive; harder to apply in formulaic ways. Comparison: Morin's integralism is more epistemologically modest and pluralistic than Wilber's developmental teleology. Metamodernism (Hanzi Freinacht et al.) Focus: Reconciliation between modern and postmodern sensibilities; cultural development; psychological growth. Strengths: Politically engaged; seeks actionable synthesis without cosmic metaphysics. Weaknesses: Still evolving; sometimes lacks philosophical depth. Comparison: Shares IT's interest in development, but does so with more irony and less metaphysical certainty. Process Philosophy (Whitehead, Cobb, Hartshorne) Focus: Reality as process, creativity, and relational becoming. Strengths: Offers an alternative metaphysics compatible with experience and novelty. Weaknesses: Dense and abstract; not easily applied across fields. Comparison: IT draws on process ideas, but overlays them with a theosophical evolutionary narrative that Whitehead would not endorse. So—Is Integral Theory a Good Metatheory?It depends on what one is looking for: If your aim is to integrate inner experience with outer knowledge, IT offers a powerful and ambitious synthesis. If your concern is philosophical clarity and empirical rigor, IT often disappoints. If you're a practitioner seeking a broad conceptual map for growth or coaching, IT can be quite useful. If you're a theorist concerned with intellectual humility, methodological transparency, or ontological caution, IT may seem overreaching. Ultimately, a good metatheory should not just integrate widely but do so well. That means respecting the epistemological boundaries of its sources, remaining open to revision, and resisting the temptation to convert mystery into metaphysics. ConclusionKen Wilber's Integral Theory is one of the most visionary metatheories of the late 20th and early 21st century. Its ambition is admirable, and its cultural influence is significant—particularly in the domains of spirituality, leadership, and education. But as a metatheory, it must be judged by its ability to coordinate disparate domains with rigor, coherence, and critical reflexivity. On these grounds, IT stands as a flawed but fascinating model: rich in scope, imaginative in vision, but weakened by metaphysical inflation and developmental idealism. In the end, the question is not whether IT includes everything, but whether it does so responsibly.

|