|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020). Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020).

Check out my other conversations with ChatGPT

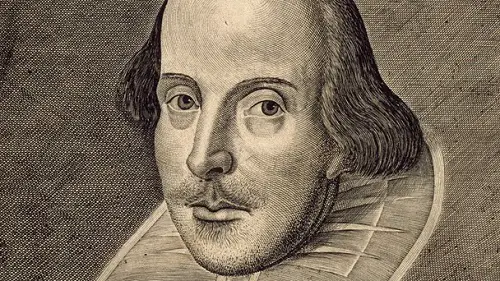

From Atoms to ShakespeareThe Driven Dance of EvolutionFrank Visser / Grok 3 “Neo-Darwinian evolutionary theory holds that all these transformations upward were just the result of chance and randomness. But there is no way in hell that the universe went from atoms to Shakespeare out of random stabs. This is an extraordinarily driven process”. - Ken Wilber[1]

The error in Wilber's approach lies not in his intuition but in his reliance on metaphysical language over testable hypotheses.

Ken Wilber's provocative claim challenges the foundations of modern evolutionary biology. By rejecting the notion that randomness alone could account for the emergence of life's complexity—culminating in cultural achievements like Shakespeare's works—Wilber posits a purposeful, directed force in evolution. His assertion sparks profound questions about the interplay of chance, selection, self-organization, and purpose in the universe's trajectory. However, it also invites critical scrutiny: does his “driven process” echo creationism, threatening scientific inquiry? Does invoking a universal “drive” akin to Eros signal pseudoscience? Does Wilber mischaracterize neo-Darwinism by overstating the role of chance, creating a strawman that ignores the contributions of selection and other natural laws? And does his appeal to a spiritual dimension misinterpret the scientific consensus on self-organization? This essay explores these tensions, weaving Wilber's philosophical provocation with scientific and critical perspectives that challenge its implications. Neo-Darwinian theory, built on Darwin's insights and modern genetics, explains life's diversity through natural selection acting on random genetic mutations. Over billions of years, these mutations, filtered by environmental pressures, transformed simple molecules into organisms capable of producing Hamlet. The model's elegance lies in its mechanistic clarity, but Wilber argues that the leap from atoms to Shakespeare—a symbol of human consciousness, creativity, and cultural depth—cannot be explained by “random stabs.” His phrase “extraordinarily driven process” suggests a teleological force, a directionality pulling life toward complexity and meaning. This view evokes awe at the universe's capacity to produce not just biological forms but profound cultural achievements, yet it raises concerns about its scientific legitimacy and philosophical implications. A key critique of Wilber's stance is that it misrepresents neo-Darwinism by framing it as overly reliant on chance, creating a strawman. Nobody in science believes chance explains everything; evolution is a complex interplay of random mutations, natural selection, genetic drift, and other natural laws like thermodynamics and biochemistry. Selection, in particular, is a non-random process that filters variations based on environmental fitness, shaping life's trajectory. For example, the development of the eye, often cited as a marvel of complexity, results from cumulative adaptations favored by selection, not blind luck. By emphasizing “random stabs,” Wilber overlooks these deterministic mechanisms, exaggerating the role of chance to bolster his case for a driven process. This misrepresentation risks undermining his critique, as it engages with a caricature of evolutionary theory rather than its nuanced reality. Another concern is that Wilber's “driven process” risks echoing creationist arguments, which invoke purposeful intelligent design to explain life's complexity. Creationism, often rooted in religious frameworks, posits a conscious agent orchestrating evolution—a claim science rejects for its lack of testable evidence. Wilber's suggestion of a non-random force, while not explicitly theistic, could be seen as a softer version of this, potentially halting scientific inquiry by attributing outcomes to an inscrutable purpose. For instance, explaining Shakespeare's genius as the result of a cosmic drive might discourage investigation into the genetic, environmental, and cultural factors that shaped such a mind. Science thrives on dissecting mechanisms, not invoking ineffable forces, and Wilber's language treads a fine line between philosophical speculation and creationist undertones that could be seen as anti-scientific. However, Wilber's integral philosophy complicates this critique. Unlike creationism, which often denies naturalistic mechanisms, Wilber does not reject evolution's biological foundations. Instead, he argues that neo-Darwinism's focus on randomness overlooks a broader context: the universe's capacity for self-organization. Science widely acknowledges self-organization as a factor alongside natural selection. Researchers like Ilya Prigogine and Stuart Kauffman have shown how complex systems, from chemical reactions to ecosystems, spontaneously generate order under certain conditions. Dissipative structures, for example, maintain complexity by dissipating energy, suggesting that life's emergence and evolution involve inherent organizing principles. Wilber's “driven process” could align with these ideas, framing evolution as an emergent phenomenon rather than a series of random accidents. Yet, what science denies is that self-organization implies a spiritual Eros—a life-affirming, purposeful force akin to the mythological concept. While self-organization is a measurable, physical process, Wilber's suggestion of a metaphysical drive lacks empirical grounding, risking dismissal as a poetic overreach rather than a scientific hypothesis. The invocation of Eros, or a similar universal drive, further fuels concerns about pseudoscience. Pseudoscientific claims often rely on grandiose, untestable assertions that sound profound but evade scrutiny. Wilber's “extraordinarily driven process” evokes a sense of cosmic purpose, but without clear criteria for testing its existence, it remains speculative. For example, how would one measure Eros in evolution? Could its influence be distinguished from the effects of selection or self-organization? Science requires falsifiable predictions, and Wilber's language, while evocative, lacks the specificity to meet this standard. If his drive is merely a rebranding of emergent complexity, it adds little to existing theories. If it implies a vitalistic or spiritual force, it ventures beyond science's domain, resembling the untestable claims of pseudoscience. The challenge is to articulate a mechanism for this drive—perhaps through complexity theory or epigenetics—that could bridge Wilber's intuition with empirical rigor. Moreover, Wilber's emphasis on an “upward” trajectory from atoms to Shakespeare assumes a linear progression that oversimplifies evolution's complexity. Evolution is not a ladder but a branching tree, marked by dead ends, regressions, and diverse adaptations. Many organisms, like bacteria, thrive in simplicity, challenging the notion of a universal drive toward complexity. Shakespeare's emergence, while remarkable, is a contingent outcome of specific biological and cultural conditions, not a cosmic inevitability. Wilber's focus on humanity's cultural pinnacle may reflect an anthropocentric bias, projecting purpose onto a process that may lack inherent direction. Neo-Darwinism, by contrast, embraces this lack of teleology, viewing evolution as a series of local adaptations shaped by selection and other laws, not a grand narrative. Despite these critiques, Wilber's perspective challenges scientific complacency. By questioning the sufficiency of randomness, he highlights gaps in neo-Darwinism's explanatory power, even if his characterization of it as purely chance-driven is flawed. Self-organization, widely accepted in science, suggests that evolution involves more than chance and selection, even if it does not require a spiritual Eros. Thinkers like Teilhard de Chardin, who envisioned evolution as a journey toward consciousness, or Kauffman, who explores self-organization's role in complexity, offer frameworks that resonate with Wilber's ideas without abandoning science. The error in Wilber's approach lies not in his intuition but in his reliance on metaphysical language over testable hypotheses. A rigorous synthesis of his ideas with science would require identifying mechanisms—perhaps in network theory or emergent systems—that could account for a “driven” quality without invoking untestable forces. Ultimately, Wilber's quote is a call to expand our imagination, not reject science. His rejection of “random stabs” as the sole driver of evolution does not necessitate creationism but underscores the limits of overly simplistic narratives. The universe's journey from atoms to Shakespeare, blending biological and cultural evolution, is indeed extraordinary. Whether this reflects a physical process of self-organization, a cosmic drive, or the improbable beauty of selection and natural laws, Wilber's words ignite wonder at a universe capable of producing both stars and sonnets. The challenge is to honor this wonder while grounding inquiry in the empirical rigor that keeps science vibrant. NOTES[1] The Guru and the Pandit [Ken Wilber and Andrew Cohen], "Eros, Buddha, and the Spectrum of Love", EnlightenNext, nr. 47, 2011 (taken offline). See also: Frank Visser, "No Way in Hell", Ken Wilber on the Naturalistic Approach to Evolution, October 2019.

|