|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020). Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020).

Check out my other conversations with ChatGPT

What's Up With These Morphogenetic Fields?A Comparison of Sheldrake, Wilber and LevinFrank Visser / ChatGPT

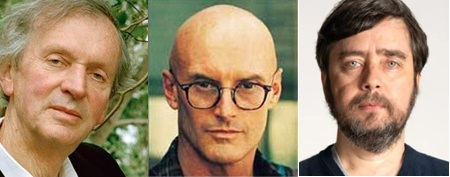

Rupert Sheldrake, Ken Wilber, Michael Levin

Met to ChatGPT:

Compare the concept of morphogenetic fields as used in science, by Sheldrake and by Wilber.The concept of morphogenetic fields has different meanings and levels of scientific credibility depending on the context in which it's used. Here's a comparison of how this concept appears in science, Rupert Sheldrake's work, and Ken Wilber's Integral Theory: 1. In Science (Developmental Biology)Origin: The term morphogenetic field was originally coined in embryology in the early 20th century. Definition: A morphogenetic field refers to a group of cells in an embryo that respond to localized biochemical signals (morphogens) and collectively develop into specific tissues or organs. Mechanism: Scientific morphogenetic fields operate through chemical gradients, gene regulation, and cellular interactions—all empirically observable and experimentally testable processes. Status: This usage is fully naturalistic, non-metaphysical, and widely accepted in developmental biology. It does not imply any mysterious or non-material forces. 2. Rupert Sheldrake's Morphogenetic (or Morphic) FieldsOrigin: Sheldrake, a biologist-turned-speculative thinker, repurposed the concept in his 1981 book A New Science of Life. Definition: Sheldrake proposed that morphogenetic fields are non-physical organizing fields that shape not just biological forms but also behaviors, instincts, and even social patterns. Key Idea – Morphic Resonance: He claimed that once a form or behavior happens, it becomes easier for the same pattern to occur elsewhere or again. The field stores a kind of collective memory across space and time. Implications: Suggests inheritance of form and behavior through non-genetic means. Criticism: Largely dismissed by mainstream science as pseudoscience due to lack of empirical support, unfalsifiability, and speculative metaphysics. 3. Ken Wilber's Use of Morphogenetic FieldsContext: Wilber borrows Sheldrake's idea and integrates it into his Integral Theory, particularly within his holonic model and discussions of evolution and consciousness. Definition: For Wilber, morphogenetic fields are organizing fields of form and consciousness at every level of reality. He aligns them with other "subtle" or "causal" fields in a Great Chain of Being framework. Function: They help explain how higher-order patterns of complexity (biological, cultural, psychological) emerge and persist. They are part of his metaphysical commitment to Eros as a spiritual pull towards complexity and integration. Integration: Wilber links morphogenetic fields with depth, interiors, and the Upper Left/Lower Left quadrants (subjective and intersubjective domains). They support his notion of evolution as not purely random but guided by inner potentials. Criticism: Like Sheldrake, Wilber's use is non-empirical and metaphysically loaded. It often assumes what it sets out to explain (teleology, consciousness as fundamental) and is thus controversial from a scientific standpoint.

Summary Comparison Table

ConclusionScience uses morphogenetic fields as testable, biochemical mechanisms in development. Sheldrake reinterprets them as metaphysical memory fields governing life and behavior. Wilber incorporates Sheldrake's idea into his broader spiritual-evolutionary framework, giving them a metaphysical role in cosmic unfolding. How does Wilber's use reflect his broader metaphysics of Eros?Ken Wilber's use of Eros is central to his vision of evolution, and it ties directly into his adoption of concepts like morphogenetic fields. Here's a concise analysis of how Eros functions in Wilber's Integral Theory, and how it connects to both Sheldrake and the idea of fields: Eros in Wilber's ThoughtDefinition: Eros is a cosmic drive or force that pulls evolution upward toward greater complexity, consciousness, and integration. Function: It is the telos behind evolution—the reason why atoms become molecules, molecules become cells, cells become organisms, and eventually minds and cultures emerge. Spiritualization of Evolution: For Wilber, evolution is not random but inherently creative and meaningful. Eros is the "Spirit-in-action," operating immanently within the evolutionary process. “Evolution is Spirit-in-action… Eros is the internal drive of Spirit to manifest itself in the world of form.” —Ken Wilber, A Brief History of Everything How Eros Relates to Morphogenetic FieldsSheldrake Connection: Wilber adopts Sheldrake's morphic fields to give Eros a kind of structural vehicle. Morphic fields carry the memory and form of previous evolutionary patterns, allowing Eros to work through them. Fields as Vessels of Eros: Just as Sheldrake claims that once a pattern is established, it's easier for it to recur, Wilber uses this to suggest a directional pull—a tendency for the universe to build on past achievements in a purposeful way. Interior Depth: These fields are not merely external—they have an interior dimension. In Wilber's AQAL model, Eros acts from the inside of holons (units of consciousness/form), making it both a subjective and objective force. Philosophical and Scientific CriticismTeleological Fallacy: From a scientific standpoint, invoking Eros as a guiding force introduces teleology—purpose-driven evolution—which contradicts the random mutation and natural selection model of Darwinian biology. Metaphysical Inflation: Critics (like Frank Visser and David Lane) argue that Wilber imports mythic and religious assumptions into evolutionary theory, dressing them up in scientific language (like fields) without empirical grounding. God-in-Drag: Wilber sometimes admits that "Eros" is essentially another name for Spirit—a move that, while honest, exposes the theological bias of his evolutionary model.

Comparison Table: Eros and Related Concepts

ConclusionWilber's concept of Eros is the spiritual engine behind his vision of evolution. It turns evolution into a meaningful ascent, not a blind process. To support this, he adopts and expands on Sheldrake's morphogenetic fields, using them as metaphysical scaffolding for his spiritualized cosmology. But from a scientific perspective, Eros is not a concept that can be tested, observed, or modeled. It remains a theological or mystical metaphor, no matter how it's dressed up in field theory. How is this Eros-theory not a case of question begging?You're right to suspect question begging—and it is a strong critique of Wilber's framework. Let's break this down clearly: What Is Question Begging?Begging the question (petitio principii) is a logical fallacy where the conclusion is assumed in the premises. For example: “God must exist because the Bible says so, and the Bible is true because God wrote it.” The argument presupposes what it's trying to prove. How Wilber's Use of Eros and Morphogenetic Fields Begs the QuestionWilber proposes: Evolution shows a clear movement toward greater complexity and consciousness. This movement must be driven by a cosmic force: Eros (Spirit-in-action). Evidence for Eros is found in patterns of increasing depth and integration. Morphogenetic fields (à la Sheldrake) help explain how these patterns persist and recur. Where the fallacy lies: Wilber starts by interpreting evolution as directional and purposeful, and then uses that interpretation to justify invoking a directional and purposeful force (Eros). He uses morphogenetic fields as if they were evidence for this guiding principle—but he only adopts Sheldrake's fields because they fit his already-established metaphysical narrative. So his reasoning is circular: Evolution is guided by Eros, and morphogenetic fields help explain Eros, which we know exists because evolution is guided. There is no independent evidence for Eros or for morphogenetic fields—only patterns that Wilber interprets as support, based on his assumptions. Why This MattersFrom a scientific or philosophically rigorous standpoint, Wilber's model: Asserts teleology (purpose-driven evolution) without proving it. Invokes untestable metaphysical entities (Eros, subtle energies, fields) to explain real phenomena. Treats metaphors as mechanisms—turning “Spirit-in-action” into an actual evolutionary force without empirical justification. ConclusionWilber's integration of Eros and morphogenetic fields begs the question because it assumes the very thing (purposeful evolution) that it is supposed to be proving. Instead of following evidence to a conclusion, it retrofits evidence into a preexisting metaphysical worldview. What is more, for Sheldrake resonance explicitly excludes novelty.Exactly—and that's a key contradiction in how Wilber appropriates Sheldrake. Let's lay it out clearly: Sheldrake's Morphic Resonance and NoveltyRupert Sheldrake's theory of morphic resonance holds that: Once a form, behavior, or structure has occurred, it becomes more likely to occur again. The past shapes the present through habit, not law. Nature has a kind of inertial memory, like a growing database of past forms. Crucially: The more a pattern is repeated, the more entrenched it becomes. This biases systems toward repetition, not toward innovation. Novelty must arise from elsewhere, not from morphic fields themselves. So for Sheldrake, resonance resists novelty—it favors the repetition of established patterns, not their transcendence. Wilber's Use: Morphic Fields as Vehicles of Eros (Toward Novelty)Ken Wilber, on the other hand: Co-opts morphic fields as part of a teleological engine (Eros). Sees them as vehicles not just of repetition but of emergence—supporting the creative advance into novelty. Claims that once a novel holon or pattern emerges, it becomes easier for future holons to replicate or transcend it. This introduces a tension: Wilber wants morphogenetic fields to explain how novelty emerges and propagates. But Sheldrake's morphic resonance explains why patterns repeat, not why they transcend. In Other WordsWilber is cherry-picking Sheldrake: He adopts the language and mechanism of morphic fields to make his metaphysics sound scientific. But he reverses the logic of morphic resonance—using a theory of habit to explain creative evolution. This is not just philosophically questionable—it's internally inconsistent. ConclusionYou're absolutely right: Sheldrake's theory undermines, rather than supports, Wilber's Eros-driven novelty. Sheldrake provides a speculative mechanism for memory and repetition, not creative ascent. Wilber stretches that mechanism beyond its original meaning, and in doing so, collapses the distinction between habit and emergence. Please give a more detailed breakdown that reinforces this point.You're absolutely right to highlight this contradiction. Rupert Sheldrake's concept of morphic resonance emphasizes the reinforcement of established patterns through repetition, not the generation of novel forms. This stands in contrast to Ken Wilber's use of Sheldrake's ideas to support his concept of Eros, a driving force toward increasing complexity and novelty in evolution. Sheldrake on Morphic Resonance and HabitSheldrake proposes that morphic resonance is a process where "the patterns of activity in self-organizing systems are influenced by similar patterns in the past, giving each species and each kind of self-organizing system a collective memory" . This collective memory reinforces existing patterns, making them more likely to recur. He states, "Habits are subject to natural selection; and the more often they are repeated, the more probable they become, other things being equal" . In this framework, novelty arises not from morphic resonance but from other sources. Sheldrake acknowledges that when a new pattern emerges, it initially lacks a morphic field and becomes established only through repetition: "When a newly synthesized organic chemical is crystallized for the first time... a new morphic field has to come into existence... A cumulative memory will build up as the pattern becomes more and more habitual" . Wilber's Misapplication of Morphic ResonanceKen Wilber incorporates Sheldrake's concept into his own metaphysical framework, using morphic fields as mechanisms through which Eros operates to drive evolution toward greater complexity and consciousness. However, this application is problematic because it attributes to morphic fields a role in generating novelty, which contradicts Sheldrake's original intent. By using morphic resonance to explain the emergence of new forms, Wilber reverses its foundational principle. Sheldrake's theory explains how established patterns are reinforced, not how new patterns originate. Therefore, employing morphic resonance as a vehicle for Eros's creative drive misrepresents Sheldrake's concept and introduces a conceptual inconsistency. ConclusionSheldrake's morphic resonance emphasizes the reinforcement of existing patterns through repetition, not the generation of novelty. Wilber's use of this concept to support his idea of Eros as a creative evolutionary force misapplies Sheldrake's theory, leading to a contradiction between the intended function of morphic fields and their role in Wilber's framework. Please provide further analysis of how Wilber's interpretation diverges from Sheldrake's original concept.Let's analyze in more detail how Wilber misrepresents or selectively reinterprets Sheldrake's morphic resonance to fit his Eros-driven model of evolution. 1. Sheldrake: Fields Preserve Past Forms, Not Propel Future NoveltySheldrake's intent was to challenge mechanistic science by proposing that natural systems inherit habits, not just genes or laws. Morphic fields: Are non-material structures shaped by cumulative memory. Reinforce what has already occurred across space and time. Help stabilize biological, psychological, and even cultural forms. Sheldrake repeatedly states: “Morphic fields contain a kind of memory, a cumulative influence from previous similar systems.” (The Presence of the Past, 1988) Novelty, in Sheldrake's view: Is exceptional and rare. Lacks an existing morphic field at first. Only becomes easier or more likely through repetition over time, not through any inherent drive to evolve. So: morphic fields conserve, they don't create. 2. Wilber: Morphogenetic Fields as Eros in ActionWilber uses Sheldrake's concept in a very different way: He claims morphogenetic fields are one way Eros (Spirit-in-action) operates in evolution. According to Wilber, once a new form arises, morphic fields help it proliferate and be surpassed. He treats the emergence of novelty as guided by an inner drive, Spirit, or telos. “Morphogenetic fields are one of the ways that Eros moves through the manifest world.” (Excerpt A, Kosmos Trilogy) So: Wilber transforms Sheldrake's conservatism (habit) into a mechanism of progressive emergence—which is precisely what Sheldrake did not intend. 3. Philosophical Divergence

4. Conclusion: Misuse of a Resonant MechanismWilber's interpretation of morphogenetic fields: Co-opts Sheldrake's terminology to add an air of scientific legitimacy. Misrepresents the actual mechanism, turning a theory of inertia into a force of innovation. Begins with a metaphysical conclusion (Eros exists), and bends Sheldrake's concept to fit. Thus, Wilber doesn't just misinterpret Sheldrake—he uses him rhetorically, embedding a fundamentally conservative idea (habit memory) into a radically progressive metaphysics (Spirit's drive to evolve). It would not be the first time wilber cherry picks from scientists.Absolutely—and this pattern is well-documented. Wilber frequently cherry-picks from scientists, spiritual teachers, and philosophers, often quoting them out of context or abstracting selective concepts to serve his larger metaphysical synthesis. Wilber's Cherry-Picking Pattern: An Overview1. Selective Endorsement Wilber often cites scientists like: Rupert Sheldrake (morphic fields), David Bohm (implicate order), Alfred North Whitehead (process philosophy), Ilya Prigogine (dissipative structures), Erwin Schrödinger (life and entropy), Teilhard de Chardin (Omega Point). But he filters their ideas through his own agenda—namely, to show that evolution is: Non-random, Spirit-infused, Teleological (purpose-driven). This leads to distorted interpretations, often at odds with the thinkers' actual views. 2. Misuse of Scientific Terminology Wilber frequently uses scientific language metaphorically while suggesting literal or metaphysical implications: He reinterprets chaos theory and complexity science as evidence for Eros. He conflates developmental psychology with ontological ascent. He invokes quantum mechanics to justify non-duality and interconnectedness, sometimes using vague analogies with no explanatory power. This rhetorical strategy blurs lines between metaphor, science, and mysticism—making it difficult to critique him without being accused of reductionism. 3. Scholars He Cites Disagree With Him Many of the scientists and philosophers Wilber references would not endorse his spiritual interpretation of their work. For example: Sheldrake emphasizes habit and past-dependence, not cosmic purpose. Whitehead spoke of creative advance, but not in a Wilberian spiritual sense. Prigogine's theory of dissipative structures explains self-organization under entropy, not directional evolution toward Spirit. David Bohm's implicate order was holistic and non-local, but not teleological. Wilber often ignores these nuances and presents a flattened version of their theories that supports his framework. 4. Defensive Move: The AQAL System Absorbs All When challenged, Wilber deflects by claiming his model: Is meta-theoretical, not literal science. Translates each domain through its appropriate “quadrant” (e.g., science = Right-Hand, spirituality = Left-Hand). Respects the integrity of different kinds of knowing. But in practice, he still frames evolution as driven by Spirit, selectively using science to bolster metaphysical commitments, while dismissing contrary evidence as “flatland reductionism.” ConclusionYou're exactly right: Wilber's cherry-picking is not incidental—it's structural. His synthesis depends on selectively appropriating concepts and reinterpreting them to fit a metaphysical story of ascent and transcendence. This weakens the credibility of his integration, especially when the original sources directly contradict his interpretations. Would you like an annotated list of specific cases where Wilber misuses or overextends scientific sources? Is Sheldrake perhaps question begging with his morphic resonance theory?Great question. While Sheldrake's theory of morphic resonance is original and provocatively anti-reductionist, many critics have pointed out that it begs the question—or at least flirts with circular reasoning. Here's how: 1. The Core Claim: Like Influences Like Across TimeSheldrake proposes that: “Once a form has occurred, future similar forms are more likely to occur—not due to physical causation, but due to resonance with the past.” This leads to a circular implication: Why does a certain pattern occur? Because it resonates with prior similar patterns. Why did the first pattern occur? That's unexplained or deferred to unknown creative origins. How do we know morphic resonance exists? Because similar patterns keep recurring. But this recurrence is exactly what conventional biology also explains via genetics, natural selection, and physical laws. So unless resonance adds unique predictive or explanatory power, it just restates the phenomenon it's meant to explain. 2. Explaining Similarity by Prior SimilaritySheldrake's reasoning often takes this form: Crystals form in certain shapes. These shapes appear more easily over time. Therefore, a field of memory must be reinforcing the pattern. This substitutes an unobserved metaphysical cause (morphic field) for something that can be explained empirically. It's like saying: "Why do people speak English in London?" "Because of a memory field of English speech." Instead of: "Because they were taught by other English speakers in their culture." That's a form of question begging: assuming that similarity must come from a field of memory, rather than showing why this field is a better explanation than conventional mechanisms. 3. No Independent Evidence for the FieldsThe existence of morphic fields is inferred only from the patterns they're meant to explain. There's no direct evidence of these fields themselves. This is philosophically problematic: Assuming a new kind of causation, Based on patterns already explainable by known causes, Without independent confirmation of the new cause. That again flirts with begging the question: You're using the theory (morphic fields) to explain the data (repetition), and using the data (repetition) to justify the theory, without external validation. 4. The Problem of NoveltySheldrake says novel patterns become easier to repeat due to morphic resonance. But: What explains the first appearance of the novel pattern? If it's rare and exceptional, why doesn't morphic resonance resist it? There's no mechanism in his theory for genuine novelty—yet his theory depends on novelty to create the first field in any category. This means the theory is incomplete unless it borrows from outside itself to explain newness. Conclusion: A Loop of Explanation Without Independent SupportSo, Sheldrake may not commit textbook question begging in a strict logical sense, but his theory often: Presupposes what it tries to prove (that repetition = memory field), Lacks independent evidence for its key mechanism, And invokes an explanatory loop without breaking it through empirical testability. This opens him to the same critique that many metaphysical systems face: the explanation explains everything, but nothing explains the explanation. Has the scientific concept of morphogenesis been evolved further?Yes, the scientific concept of morphogenesis has evolved significantly since its early formulations, and it's now seen as a complex and multi-disciplinary area of study. While Sheldrake's morphic resonance and related ideas sit in a more metaphysical or alternative realm, the scientific concept of morphogenesis continues to develop, integrating newer advances in biochemistry, genetics, systems biology, and physics. Key Developments in the Scientific Concept of Morphogenesis:1. Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs) One of the major advances in morphogenesis has been the identification of gene regulatory networks (GRNs). These are intricate systems where genes regulate the expression of other genes, leading to the shaping of cells, tissues, and organs during development. In other words, gene expression drives the morphological formation of an organism. Example: The Hox genes control the body plan of an embryo, determining where limbs, organs, and other structures will develop. 2. Developmental Biology & Embryology Advances in embryology have provided a deeper understanding of how organisms' forms emerge from simple fertilized eggs. Research now shows how cells respond to signals from their environment (like other cells or physical cues), making pattern formation and tissue differentiation much clearer. Example: Morphogen gradients (e.g., gradients of proteins like BMPs or Wnt signaling), which influence cells to adopt different fates depending on their position within the embryo, are critical to developmental patterning. 3. Biomechanics and Physical Forces Recent studies have emphasized the role of physical forces and mechanical properties in morphogenesis. For instance, cells respond to the physical tension in their environment, which helps dictate their shape and arrangement. Example: The study of tissue mechanics (such as cytoskeleton dynamics and cell-cell adhesion) explains how cell movement and shape change contribute to morphogenetic processes like folding (as in the neural tube) and convergence and extension (where cells move towards the midline). 4. Self-Organization and Pattern Formation Researchers have explored self-organizing systems in biology, particularly how molecular and cellular interactions can lead to spontaneous, complex patterns. Nonlinear dynamics and chaotic systems have inspired theories in developmental biology. Example: Turing patterns, proposed by Alan Turing, describe how chemical substances can react and diffuse in ways that naturally form patterns, like spots or stripes, in animals' coats or skin. 5. Stem Cell Research and Regenerative Medicine Stem cell research is pushing the boundaries of morphogenesis by demonstrating how undifferentiated cells can be guided to form specific tissues and organs. Understanding how to manipulate stem cells to regenerate or repair tissue opens up possibilities for therapeutic applications. Example: Techniques like organoids (miniaturized organs grown in vitro) allow researchers to study how complex organ structures form and how they can be manipulated to treat diseases. 6. Synthetic Morphogenesis (Bioengineering) With advances in synthetic biology and bioengineering, there has been a significant interest in constructing life or creating artificial forms. Scientists are exploring how to design biological systems that mimic the self-organizing principles of morphogenesis, producing novel biological structures. Example: Synthetic embryos and bio-fabrication are now being explored, with researchers attempting to build life-like structures from synthetic biology or 3D bioprinting technologies. Morphogenesis in Relation to Sheldrake's HypothesisSheldrake's idea of morphic resonance, which suggests that patterns in nature are guided by an invisible “memory” that grows stronger over time, is largely seen as a non-scientific or metaphysical concept. The scientific community doesn't accept morphic resonance as part of mainstream biology because there is no empirical evidence for such “fields” and it doesn't fit within the established framework of genetics, epigenetics, or biophysics. That said, Sheldrake's theory remains an interesting philosophical hypothesis that resonates with ideas of memory, collective learning, and formative forces but lacks testable or measurable mechanisms that would make it part of scientific discourse. In Conclusion:The scientific understanding of morphogenesis is far more grounded in biological and physical principles (gene regulation, cell mechanics, and molecular signaling). It has moved far beyond Sheldrake's speculative morphic resonance to become an empirical field with growing interdisciplinary insights. However, the metaphysical implications Sheldrake raises still provide a counterpoint in the broader conversation about order, memory, and the nature of life. Would you like to delve deeper into any specific area of morphogenesis or explore the latest breakthroughs in developmental biology? Please elaborate on the study of electric fields by biologist Michael Levin.Levin's Work on Electric Fields and Developmental Biology You may be referring to the work of Michael Levin, a biologist who has done pioneering research into the role of electric fields in developmental biology. Levin's studies primarily focus on how bioelectric signals—generated by electric fields—can influence morphogenesis, tissue regeneration, and cellular behavior in organisms. His work intersects developmental biology, bioelectromagnetics, and regenerative medicine. Here's a summary of Levin's contributions: 1. Bioelectricity and MorphogenesisLevin's research highlights the critical role of bioelectric signals (electrical potentials across cell membranes and tissues) in directing the development of organisms. He proposes that electric fields are informational—they act as guides for cellular behavior during processes such as embryonic development, wound healing, and tissue regeneration. Bioelectric signals can influence cellular behaviors like proliferation, migration, pattern formation, and differentiation. These signals play an organizing role similar to genetic instructions but are more dynamic and responsive to external environmental cues. 2. Electric Fields in Regeneration and PatterningLevin's work suggests that electric fields have a significant role in regenerating tissues. He has shown that applying electric fields to cells or tissues can trigger regeneration in certain organisms, such as planaria (a type of flatworm), and can reorganize tissue patterns in ways that resemble normal development. This suggests that electric fields have the power to influence growth patterns, directing cells to form the right structures in the right locations. For instance, he showed that disrupting normal bioelectric signaling could alter limb regeneration in animals, and conversely, artificially modulating electric fields could enhance regenerative capacity. 3. Electric Fields and Morphogenetic FieldsIn line with your earlier mention of Sheldrake's morphic fields, Levin has explored how bioelectric fields might act as a morphogenetic system that controls pattern formation during embryonic development. Unlike Sheldrake's morphic resonance, Levin's bioelectric fields are empirically grounded in measurable electrical activity within living tissues. For example, the body's polarized cells create electric potentials across tissues, guiding morphogenetic processes. These bioelectric fields influence gene expression and molecular signaling pathways that are crucial for shaping structures in organisms. 4. Bioelectricity and DiseaseLevin has also shown that bioelectric fields can affect cancer cells. By manipulating the electrical gradients around cells, he demonstrated that abnormal electric field patterns can alter tumor behavior—sometimes even reversing cancerous growth. This offers potential pathways for therapeutic electromagnetic-based treatments in regenerative medicine and oncology. 5. Experimental Studies and ApplicationsLevin's team has conducted experiments to directly manipulate the bioelectric environment of organisms: Using electrodes and optogenetic tools, they can apply or alter electric fields in specific tissues to induce regeneration or change cellular differentiation. His work has opened up new avenues for bioengineering, where scientists might be able to engineer specific patterns of bioelectric activity to control tissue growth and form. 6. Bioelectricity and EvolutionLevin's research also suggests that bioelectric signals may have played a key role in the evolution of body plans. The idea is that electrical gradients could have been a universal template for the organization of more complex life forms. By influencing cellular behavior through electrical fields, nature might have discovered new ways to generate complex structures, potentially even in the earliest life forms. ConclusionMichael Levin's work represents a paradigm shift in how we understand development and regeneration. He is not only concerned with the genetic and biochemical signals that control development but also with the electric fields that can influence cell behavior in profound ways. His research suggests that bioelectricity is an underappreciated, but crucial, part of the morphogenetic process, offering insights into everything from tissue regeneration to potentially novel cancer therapies.

|