|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020). Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020).

Check out my other conversations with ChatGPT

REFLECTIONS ON BOBBY AZARIAN'S MODEL:

Review of "The Romance of Reality" From Big Bang to Omega The Romance of Explanation Three Stories of Reality Rethinking the Nature of Nature The Clash of Paradigms

From Big Bang to OmegaCompeting Visions of Cosmic Meaning

|

| Feature | Whitehead (Process View) | Intelligent Design (ID) |

|---|---|---|

| Creation | Eternal process; no creatio ex nihilo | Often assumes finite creation |

| God | Persuasive, evolving, non-omnipotent | Powerful designer, possibly omnipotent |

| Mechanism | Co-creative evolution; God offers possibilities | Designer intervenes in natural processes |

| Scientific Compatibility | Philosophically aligned with science | Claims scientific basis, but widely seen as pseudoscience |

| Teleology | Open-ended evolution toward aesthetic value | Implicit purpose, often human-centered |

How has Ken Wilber been influenced by Whitehead's philosophy?

Ken Wilber has acknowledged Alfred North Whitehead as an influence, particularly during the development of his Integral Philosophy, but Wilber's engagement is selective and filtered, blending Whitehead's process metaphysics with a strong dose of Vedanta, Theosophy, and Hegelian dialectics. Here's a breakdown of how Wilber has been influenced—and where he departs:

1. Process and Evolution

Influence:

Wilber shares Whitehead's process view of reality—a universe in dynamic becoming, rather than static being. He praises Whitehead's idea of creative advance and often references evolution as a spiritual unfolding.

Departure:

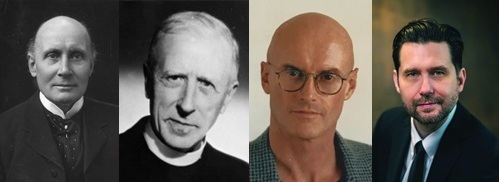

Wilber spiritualizes evolution far more than Whitehead. While Whitehead emphasized novelty, complexity, and aesthetic value, Wilber frames evolution as a telos-driven ascent of consciousness, often invoking an Eros or Spirit-in-action. This brings him closer to Teilhard de Chardin than to Whitehead's more neutral metaphysical structure.

2. Panentheism and the Role of God

Influence:

Whitehead's dipolar God (one pole timeless, the other in time) is echoed in Wilber's two truths doctrine: the nondual Absolute and the evolving relative world. Both suggest a universe where divinity is both immanent and transcendent.

Departure:

Wilber's God is ultimately impersonal and nondual, rooted in Advaita Vedanta and Mahayana Buddhism. Whitehead's God, while unconventional, still resembles a personal process deity. Wilber's framework, especially post-Sex, Ecology, Spirituality, is less theistic than Whitehead's and more metaphysically mystical.

3. Holons and Actual Occasions

Influence:

Wilber's concept of holons—entities that are both wholes and parts—has similarities to Whitehead's actual occasions, which are the basic units of experience and process.

Departure:

Whitehead's actual occasions are momentary events of experience, primarily metaphysical. Wilber's holons are more structural and hierarchical, embedded in AQAL (All Quadrants, All Levels), with clear developmental stages—something not emphasized in Whitehead.

4. Integration with Science

Influence:

Both thinkers attempt to reconcile science and spirituality through a unified metaphysics. Wilber often praises Whitehead for breaking out of mechanistic materialism.

Departure:

Wilber is less cautious than Whitehead. Where Whitehead offered a rigorous philosophical system to complement science, Wilber builds a grand synthesis using typologies and levels (e.g., pre/trans fallacy, the Four Quadrants) that many critics say lack empirical rigor. Whitehead's influence here is more inspirational than structural.

5. The Role of Consciousness

Influence:

Whitehead held that experience goes all the way down, even to atoms—a proto-panpsychist view. Wilber embraces this idea and extends it to claim consciousness is fundamental.

Departure:

Wilber often moves from panpsychism to absolute nondual consciousness, seeing Spirit as the ground of all being (One Taste). Whitehead never made such a leap; his system is metaphysically speculative but not mystical in the Vedantic sense.

Conclusion

Wilber borrows the skeleton of Whitehead's process metaphysics but grafts onto it a strong evolutionary mysticism. Whitehead is one of many sources Wilber blends into his integral synthesis—alongside Plotinus, Sri Aurobindo, Hegel, and Mahayana Buddhism. Where Whitehead is metaphysically rigorous, Wilber is more spiritually expansive.

How does Wilber resemble Teilhard de Chardin?

Ken Wilber and Pierre Teilhard de Chardin share a strong spiritual-evolutionary vision, blending cosmology, psychology, and theology into a teleological narrative of ascending consciousness. Wilber has openly praised Teilhard and echoes many of his core ideas—though he systematizes and modernizes them within his own Integral framework. Here's how they resemble each other:

1. Evolution as a Spiritual Ascent

Teilhard:

Sees evolution as moving from matter to life to mind to spirit, culminating in the Omega Point, a unification of consciousness in Christ. Evolution is not random but purpose-driven, expressing a cosmic divine impulse.

Wilber:

Frames evolution as an Eros-in-action—an inherent drive toward increasing complexity, consciousness, and depth. His AQAL model maps this ascent across physical, biological, cultural, and spiritual domains. He often cites Teilhard's idea of the Omega Point as a precursor to his own notion of nondual Spirit becoming aware of itself.

Resemblance: Both see the universe as unfolding toward a spiritual culmination, guided by an inner telos or divine aim.

2. Unity of Science and Spirit

Teilhard:

A Jesuit paleontologist, he tried to integrate evolutionary science with Christian theology, suggesting that the physical and spiritual are two sides of the same process.

Wilber:

Proposes an Integral Methodological Pluralism that respects multiple ways of knowing (science, introspection, phenomenology, hermeneutics). He insists that spirit and science can and must be integrated for a complete picture of reality.

Resemblance: Both reject the split between science and religion and aim for a grand synthesis.

3. Stages of Development

Teilhard:

Describes evolution in stages: pre-life (geosphere), life (biosphere), thought (noosphere), and divine unification (Omega Point).

Wilber:

Maps development using holarchical levels: matter ? life ? mind ? soul ? spirit, mirrored in both individual development and cultural history. His noosphere (mind layer) is directly inspired by Teilhard.

Resemblance: Both construct stage-based models of development moving toward higher unity.

4. Teleology and Eros

Teilhard:

Believes in a cosmic directionality—the universe is converging, psychically and spiritually, toward God (Omega Point). This is a Christian teleology.

Wilber:

Reinterprets this as Eros, a metaphysical pull toward greater depth and consciousness. He secularizes Teilhard's impulse while keeping its spiritual ambition.

Resemblance: Both embrace cosmic purpose—Wilber spiritualizes evolution more philosophically, Teilhard more theologically.

5. Criticism from Scientific Naturalism

Teilhard:

Criticized for infusing theology into science, and for over-interpreting evolutionary theory in religious terms.

Wilber:

Criticized for mixing mysticism with science and for making unfalsifiable metaphysical claims in the name of integration.

Resemblance: Both are visionary thinkers who challenge mainstream science, but face skepticism for importing metaphysical assumptions into evolutionary narratives.

Summary Table

| Concept | Teilhard de Chardin | Ken Wilber |

|---|---|---|

| Evolution | Cosmic ascent to Omega Point | Evolution of holons toward Spirit |

| Divine Agency | Christ as the center of convergence | Eros/Spirit-in-action |

| Integration | Science + Catholic theology | Science + psychology + mysticism |

| Developmental Stages | Geosphere → Biosphere → Noosphere → Omega | Matter → Life → Mind → Soul → Spirit |

| Influence | Catholic mysticism, evolutionary theory | Teilhard, Hegel, Vedanta, Buddhism |

Wilber is often seen as a postmodern Teilhard, replacing Catholic dogma with a trans-traditional, nondual spirituality, but maintaining the narrative arc of evolution as a sacred process.

How do these authors compare to mainstream evolutionary science?

Here is a critique comparing Wilber and Teilhard de Chardin to mainstream evolutionary science, focusing on their metaphysical assumptions, scientific validity, and conceptual pitfalls:

1. Teleology vs. Natural Selection

Teilhard & Wilber:

Both posit a teleological force—Teilhard calls it the "Omega Point" (Christic convergence), Wilber calls it "Eros" or "Spirit-in-action." Evolution, for them, is not random but has directional purpose toward increasing complexity, consciousness, and unity.

Mainstream Evolutionary Science:

Evolution is driven by natural selection, mutation, genetic drift, and environmental pressures—not by any built-in direction or goal. Evolution can result in increased complexity, but also in stasis, regression, or extinction. There is no evidence of a cosmic purpose or spiritual aim behind it.

Critique:

Their spiritualized teleology is at odds with the foundational principles of modern biology. Adding divine or metaphysical directionality risks anthropocentrism and violates methodological naturalism.

2. Spiritualization of Complexity

Teilhard & Wilber:

Increasing complexity = increasing spirituality or consciousness. Teilhard maps it to the growth of the noosphere; Wilber ties it to stages of psychospiritual development (e.g., from egocentric to worldcentric to kosmocentric).

Science:

Complexity is a physical, informational, or structural property—it does not imply consciousness or moral value. A slime mold can show emergent complexity; this doesn't mean it's spiritually evolving.

Critique:

They conflate structural complexity with inner depth, imposing a value-laden metaphysics onto neutral scientific concepts. This can lead to spiritual exceptionalism and pseudoscientific reasoning.

3. Anthropocentrism

Teilhard:

Places human consciousness at the apex of evolution, culminating in a Christic unification of minds.

Wilber:

Places human spiritual realization as the highest stage of development. His stages often lead toward nondual enlightenment, a human-centered ideal.

Science:

Homo sapiens is one of many branches of evolution. Evolution does not “aim” at humans; we are a contingent result, not a culmination.

Critique:

Their systems reinforce human-centric narratives, which modern evolutionary biology has explicitly rejected since Darwin. It risks cosmic narcissism dressed in spiritual language.

4. Use of Evolutionary Language Metaphorically

Teilhard & Wilber:

Both stretch the concept of evolution beyond biology—into culture, psychology, theology, and metaphysics.

Science:

While metaphors are useful, scientific terms like "evolution" should be precise and empirically grounded. Using them to describe spiritual development leads to category errors.

Critique:

They blur disciplines without clear boundaries. Wilber's use of "evolution" often mixes Darwinian, dialectical, and mystical meanings—muddying both science and spirituality.

5. Lack of Falsifiability

Teilhard & Wilber:

Their spiritual-evolutionary visions are unfalsifiable. There's no way to disprove the idea that the cosmos is evolving toward an Omega Point or Spirit.

Science:

Scientific theories must be testable and falsifiable. If no observation could contradict a claim, it belongs to philosophy or religion, not science.

Critique:

Their evolutionary mysticism fails Popper's criterion of falsifiability. While rich in meaning, it cannot claim scientific legitimacy without abandoning metaphysical assumptions.

Summary Table

| Feature | Teilhard & Wilber | Mainstream Evolutionary Science |

|---|---|---|

| Directionality | Evolution has a purpose/goal (Omega, Spirit) t | Evolution is undirected and contingen |

| Complexity = Consciousness | Yes — higher forms = more spiritual depth | No — complexity doesn't imply consciousness |

| Human Specialness | Humans are the summit or pivot of evolution | Humans are one outcome among many |

| Definition of Evolution | Broad, metaphysical, applied to mind/spirit | Narrow, biological, based on empirical data |

| Falsifiability | No — metaphysical and visionary | Yes — testable, evidence-based |

Final Assessment

Wilber and Teilhard offer inspiring philosophical myths—cosmic stories of growth, purpose, and spirit—but these should not be confused with scientific accounts of evolution. Their work is best seen as spiritual cosmology, not evolutionary biology.

How does Bobby Azarian's Road to Omega fit in here?

Bobby Azarian's The Romance of Reality: How the Universe Organizes Itself to Create Life, Consciousness, and Cosmic Complexity (sometimes referred to by its subtitle "The Road to Omega") is a contemporary attempt to naturalize Teilhardian and Wilberian themes—namely, the teleological drive of evolution, the rise of consciousness, and a potential cosmic destiny—while remaining within the boundaries of science (or at least claiming to).

Here's how Azarian fits into the conversation alongside Teilhard, Wilber, and mainstream science:

1. Evolving Complexity and Directionality

Azarian:

Argues that the universe shows a clear trend toward increasing complexity, from atoms to life to mind, driven by thermodynamic and informational principles. He sees this as a kind of emergent teleology, not imposed from outside, but arising from the self-organizing logic of the universe.

Similarity to Teilhard/Wilber:

Like them, Azarian suggests a "road to Omega"—a potential cosmic endpoint where intelligence and consciousness reach planetary or even universal significance.

Difference from Teilhard/Wilber:

Azarian avoids explicit spiritual metaphysics. He seeks a scientific grounding for what Teilhard and Wilber framed in theological or mystical terms. His "Omega" is technological and informational, not Christic or nondual.

2. Panpsychism and Consciousness

Azarian:

Flirts with panpsychism and the idea that consciousness could be a fundamental feature of complex systems. He references Integrated Information Theory (IIT) and complexity science, though cautiously.

Wilber:

Embraces panpsychism and nonduality, with consciousness as the interior of all holons.

Teilhard:

Implicit panpsychism; consciousness is present in rudimentary form throughout evolution, increasing in depth and complexity.

Azarian's position is more scientifically cautious, but he opens the door to a proto-consciousness embedded in matter, echoing both thinkers.

3. Science-Mysticism Bridge

Azarian:

Wants to create a "spiritual naturalism" grounded in science: awe, beauty, and transcendence through evolutionary understanding. He quotes Carl Sagan and Richard Dawkins as much as Teilhard.

Wilber:

Tries to integrate science with perennial philosophy and mystical insight. He wants not just inspiration but integral realization.

Teilhard:

Uses scientific language in service of Christian mysticism, making no pretense of strict naturalism.

Azarian tries to stay on the science side of the bridge, unlike Wilber and Teilhard who freely cross into spiritual metaphysics.

4. Omega Point and the Future of Intelligence

Azarian:

Speculates that advanced intelligence may merge into a superorganism, echoing Teilhard's noosphere and Omega Point—but through technology, AI, and networked intelligence, not divine convergence.

Wilber:

Suggests that cultural evolution may culminate in nondual awareness, where Spirit awakens to itself in and as the universe.

Teilhard:

Omega Point is a personal God, the risen Christ, fully actualized in a unified consciousness of creation.

Azarian replaces mysticism with tech-based futurism, but the structure of the narrative remains Teilhardian.

5. Reception and Critique

Mainstream Science View:

Azarian is more scientifically literate than Wilber or Teilhard, but critics may see his views as teleology dressed in entropy law language. His optimism about cosmic self-organization is not yet empirically established.

Integral View:

Azarian could be seen as an ally to Wilber, offering a scientific façade to Wilber's metaphysical intuition of evolution as Spirit-in-action.

Summary Table

| Feature | Teilhard | Wilber | Azarian | Mainstream Science |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cosmic Directionality | Yes (Christ/Omega) | Yes (Spirit/Eros) | Yes (thermo-informational) | No |

| Spiritual Dimension | Explicitly Christian | Nondual Mystical | Secular, spiritual-naturalist | Excluded |

| Consciousness View | Panpsychist-leaning | Panpsychist + Nondual | Weak panpsychism/IIT-curious | Emergent, brain-based |

| Final Endpoint | Christic unity | Realization of Spirit | Superorganism/Omega system | No final state |

| Scientific Grounding | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Strong |

Final Verdict

Azarian is a bridge figure, modernizing Teilhard's vision and echoing Wilber's evolutionary spirituality, but seeking legitimacy through thermodynamics, complexity theory, and neuroscience. He's not quite mainstream, but he's far more palatable to scientific audiences than either Wilber or Teilhard.

Even skeptic Michael Shermer praised Azarian's book!

Exactly—and that's what makes Azarian's The Romance of Reality (or “The Road to Omega”) particularly noteworthy: even scientific skeptics like Michael Shermer, who typically reject teleological or spiritual narratives, found it compelling. That signals Azarian is doing something different from Teilhard or Wilber—framing cosmic directionality in scientifically plausible terms, without crossing fully into metaphysics.

Why Shermer Praised Azarian

This praise tells us a few things:

Azarian speaks the language of science.

He grounds his argument in thermodynamics, self-organization, and complexity theory, not mystical revelation.

He offers a meaningful narrative without religion.

Shermer has long argued that humans need existential meaning without invoking supernaturalism. Azarian delivers this via a cosmic evolutionary story that retains scientific credibility.

He reclaims teleology without mysticism.

Azarian argues that the universe doesn't accidentally give rise to life and mind—it's not predetermined, but it's also not random chaos. He introduces a “directional tendency” rooted in the physics of complex systems, which Shermer sees as a naturalistic reinterpretation of purpose.

What This Means for the Wilber/Teilhard Conversation

Teilhard's metaphysical vision: Beautiful but theological; dismissed by most scientists as religious metaphor.

Wilber's Integral model: Expansive but speculative; too metaphysical for empirical science, too all-encompassing to be testable.

Azarian's model: Tells a similar cosmic story, but with scientific scaffolding. It's not airtight science, but it engages science on its own terms.

So What's the Takeaway?

Azarian is Teilhard's heir in a lab coat and Wilber's cousin with a physics degree. His "Road to Omega" story:

Resonates with the spiritual evolutionaries,

Engages the scientific rationalists, and

Offers a third path—between religion and reductionism—by telling a teleological but naturalistic narrative that even skeptics like Shermer can admire.

How does the more secular Big History school compare to this?

The Big History school offers a secular, scientifically grounded narrative of cosmic and human evolution, from the Big Bang to modern civilization. It shares some structural similarities with Teilhard, Wilber, and Azarian—especially the idea of increasing complexity—but diverges sharply in terms of teleology, spirituality, and metaphysics.

Here's a comparative breakdown:

Big History vs. Teilhard, Wilber, and Azarian

| Theme | Big History | Teilhard de Chardin | Ken Wilber | Bobby Azarian |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Origin Point | Big Bang | Big Bang, but God-infused | Big Bang, as exterior of Spirit | Big Bang, as thermodynamic seed |

| Trajectory | Complexity increases, but without direction | Increasing complexity toward Omega Point (God) | Evolution of holons toward Spirit realization | Complexity trends toward Omega-like convergence, via natural law |

| Driving Force | Emergent processes: gravity, entropy, evolution | Divine energy (Christ/Omega) | Eros or Spirit-in-action | Thermodynamic and informational self-organization |

| View of Consciousness | Emergent in brains | Latent in all matter, actualized in humans | Present in all holons (panpsychism) | Possibly fundamental or proto-conscious |

| Use of Science | Strictly empirical, naturalistic | Selective, theological overlay | Integrative but metaphysical | Scientific framing with metaphysical undertones |

| Teleology | No inherent direction or goal | Strong teleology: Christ as end-point | Strong teleology: Spirit evolves | Soft teleology: emergence of structure from physics |

| Human Role | Interesting, not privileged | Pinnacle of creation | Pinnacle of holonic development | Carrier of complexity, maybe central |

| Final State? | Unknown; open-ended | Omega Point: union with God | Nondual awakening of Spirit | Superorganismal convergence (Omega system) |

Key Differences

1. Teleology:

Big History firmly rejects any built-in purpose to evolution. Events are contingent, not preordained.

Teilhard and Wilber embrace strong teleology—history is going somewhere specific, spiritually.

Azarian introduces a naturalistic soft-teleology, claiming that laws of physics may guide complexity toward mind.

2. Use of Science:

Big Historians (e.g., David Christian, Fred Spier) stay within scientific orthodoxy, avoiding spiritual claims.

Teilhard, Wilber, and Azarian push science toward narrative or metaphysical synthesis, each to a different degree.

3. Role of Meaning:

Big History offers a "modern origin story"—intended to replace religious myths with a unifying scientific narrative, but it does not embed intrinsic meaning in the cosmos.

Teilhard and Wilber embed ultimate meaning in the evolutionary arc.

Azarian seeks a middle path, proposing that meaning can emerge from natural complexity, without supernatural elements.

Big History's Unique Contribution

It offers a disciplined chronology of the universe: Big Bang → Stars → Life → Humans → Civilization.

It's often taught in schools as a way to unite physics, biology, and history under one empirical umbrella.

It's agnostic about values and spiritual purpose, but still emotionally resonant—inviting wonder and humility.

Final Perspective

Big History is the baseline.

It's the evolutionary story without metaphysics.

Teilhard and Wilber add spiritual purpose to that story.

Azarian tries to sneak meaning and direction back in through physics and complexity science.

Each reflects a different response to the same question:

"Is there a larger meaning to the universe's story?"

Write an essay on the topics involved in rhis conversation.

Certainly. Here is a concise yet substantial essay that weaves together the key threads of our conversation:

From Big Bang to Omega: Competing Visions of Cosmic Meaning in Science and Spirituality

In recent years, a growing chorus of voices—from mystics and theologians to physicists and futurists—have attempted to tell a unified story of the cosmos, one that connects the cold mechanics of physics with the warm glow of human meaning. While the scientific community largely resists any narrative that smacks of teleology or metaphysics, thinkers like Teilhard de Chardin, Ken Wilber, and Bobby Azarian have each, in their own way, dared to suggest that evolution is not just a fact—it might also be a story with direction, purpose, and perhaps even a destination. Standing in contrast is the more sober framework of Big History, which outlines the cosmic tale from Big Bang to present without importing any spiritual or metaphysical assumptions.

At the center of this debate lies a question both ancient and contemporary: Does the universe have a direction, and if so, are we part of it?

Big History: The Secular Framework

Big History, as championed by historians like David Christian and Fred Spier, constructs a scientific narrative of increasing complexity—from the formation of atoms and stars to the emergence of life and civilizations. It is a narrative grounded in empirical observation and committed to non-teleological explanations. In this view, humans are not the inevitable crown of evolution, but an interesting outcome of contingent processes.

The Big History model has gained traction in educational and academic circles precisely because of its refusal to go beyond what science can currently justify. While it may evoke awe at the scale and intricacy of cosmic events, it offers no intrinsic meaning to them. The story, while grand, is ultimately open-ended—and possibly meaningless.

Teilhard and Wilber: Spiritualizing the Cosmos

By contrast, Teilhard de Chardin—a Jesuit paleontologist and theologian—infused the evolutionary process with explicit Christian teleology. He proposed that evolution is not merely physical, but also spiritual, culminating in the "Omega Point," a state of divine convergence in which all consciousness unites with God. For Teilhard, increasing complexity is not an accident but a signature of the divine.

Ken Wilber echoes Teilhard's themes, but within a more eclectic and transpersonal framework. Wilber's “Integral Theory” posits that reality is composed of holons—wholes that are also parts—unfolding through a nested hierarchy toward ever-greater levels of complexity, consciousness, and integration. His narrative is infused with Eastern mystical insights and Western developmental psychology. Like Teilhard, Wilber sees Spirit as the inner force of evolution—what he famously calls "Eros," or Spirit-in-action.

Both thinkers offer an enchanted vision of the universe, but one that struggles to gain traction in scientific circles due to its overt metaphysical commitments.

Bobby Azarian: Science Reclaims the Cosmic Story?

Enter Bobby Azarian, whose 2022 book The Romance of Reality (subtitled How the Universe Organizes Itself to Create Life, Consciousness, and Cosmic Complexity) attempts to straddle the divide. Azarian constructs a narrative of cosmic evolution that emphasizes increasing complexity, emergent intelligence, and a possible "Omega-like" convergence of consciousness. However, he grounds his vision not in theology or mysticism but in thermodynamics, information theory, and complexity science.

What sets Azarian apart is his ability to speak the language of science while hinting at deeper metaphysical implications. He doesn't invoke God or Spirit, but he does suggest that the universe may be "wired" to self-organize in increasingly complex ways. Consciousness, while not fully explained, is treated as a natural outgrowth of complexity—perhaps even a fundamental feature of the universe.

Remarkably, even prominent skeptics like Michael Shermer praised the book, calling it a “much-needed antidote to nihilism.” That endorsement signals a shift: perhaps even staunch empiricists are growing open to narratives that offer meaning without mysticism.

The Question of Teleology

The real dividing line among these views is teleology—whether evolution has a purpose or goal. Big History rejects this outright; for Teilhard and Wilber, it is the central premise. Azarian attempts a third way, suggesting that directionality may emerge from natural laws themselves, without recourse to the supernatural.

Yet this raises complex philosophical questions. Can direction emerge without design? Can meaning be found in processes governed by entropy and chance? Is there a scientifically coherent way to speak of an “Omega Point” without slipping into metaphysics?

Conclusion: Stories We Tell Ourselves

In the end, each of these narratives—Big History, Teilhard's spiritual evolution, Wilber's integral holarchy, and Azarian's physics of purpose—offers a different way of answering the same existential question: What is the nature of our place in the universe?

Big History offers facts, but little meaning.

Teilhard and Wilber offer meaning, but outside empirical science.

Azarian offers a potential synthesis—meaning as emergent from the laws of nature themselves.

As science advances and our existential anxieties deepen, the hunger for a meaningful story that is also scientifically plausible will only grow. Whether such a story can ever fully satisfy both reason and spirit remains the ultimate challenge.