|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020). Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020).

Check out my other conversations with ChatGPT

The Use of Metaphors in ScienceIs Eros a Bad One for Evolution?Frank Visser / ChatGPT

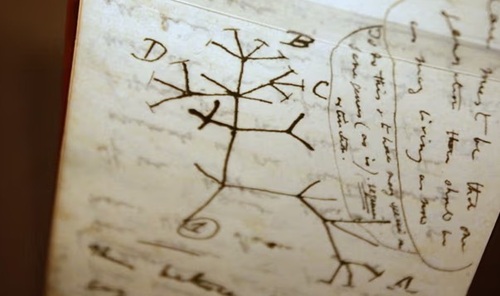

Darwin's first sketch of a possible Tree of Life annotated with "I think".

Metaphors are not just rhetorical flourishes in science; they are tools of thought. They help us grasp the invisible, the abstract, the complex. From Newton's “clockwork universe” to the “genetic code,” metaphors enable theory-building by mapping unfamiliar domains onto familiar ones. But as George Lakoff and Mark Johnson argued in Metaphors We Live By, metaphors do not merely adorn our language — they shape our cognition. They frame how we perceive the world, what questions we ask, and which answers feel satisfying. In science, they can guide discovery or misguide belief. This essay examines the power and peril of metaphors in evolutionary theory, focusing on two striking examples: Richard Dawkins' “selfish gene” and Ken Wilber's metaphysical use of Eros. While the former exemplifies a bounded, generative metaphor grounded in gene-centric evolution, the latter illustrates how metaphors can slide into mysticism and obscure scientific rigor. As a counterpoint, we revisit Darwin's original metaphors — “natural selection” and the “tree of life” — which have shaped biology for over 150 years. I argue that Eros is a misleading metaphor for evolution in scientific contexts, though it may still have value in a spiritual or poetic worldview. Metaphors: The Frameworks We Live and Think ByLakoff and Johnson's cognitive theory of metaphor reveals that metaphors are not just linguistic tricks but deep structures of thought. We don't merely say “time is money”; we conceptualize time as if it were a commodity. We spend it, waste it, invest it. These aren't turns of phrase — they are operational frameworks. Science is rich in such cognitive metaphors. We describe genes as “blueprints,” the mind as a “computer,” atoms as “solar systems.” These metaphors are indispensable for explaining phenomena, building models, and even inspiring new hypotheses. But they also constrain how we think. When metaphors reify — that is, when we forget they are metaphors — they can lead to metaphysical slippage and conceptual confusion. Darwin's Metaphors: Naturalistic and TransformativeDarwin's contribution to metaphor in science was not just linguistic genius but conceptual discipline. His metaphor of natural selection was designed to reframe the idea of design in nature without invoking a designer. Where William Paley had seen divine craftsmanship in the “watchmaker” of life, Darwin reimagined selection as a blind, impersonal filter. Organisms are not shaped by will or intention, but by differential survival and reproduction across generations. The power of natural selection as a metaphor lies in its analogy to artificial selection — the familiar process by which breeders shape traits in domesticated animals. Darwin took a known human practice and used it to illuminate a natural process. Importantly, it was only a metaphor: nature does not “select” in any conscious sense. But by anthropomorphizing nature just enough, Darwin made the process intelligible without making it spiritual. Similarly, Darwin's tree of life metaphor provided a visual schema for descent with modification. Instead of a static hierarchy (as in the Great Chain of Being), the tree suggested branching, divergence, and common ancestry. It conveyed both unity and diversity in a single organic image. The tree grows without a goal, without a final form. In contrast to Wilber's Great Nest of Being, which implies vertical ascent toward spiritual culmination, Darwin's tree is lateral, expanding, and non-teleological. Both metaphors remain central to evolutionary biology — not because they are true in a literal sense, but because they are conceptually fertile and epistemically humble. The “Selfish Gene”: Metaphor With Empirical TeethRichard Dawkins' 1976 metaphor of the “selfish gene” extended the Darwinian project by focusing on the gene as the fundamental unit of selection. Genes “compete” to propagate themselves, and organisms are seen as vehicles for gene transmission. Dawkins was clear: genes are not actually selfish — they simply behave as if they were, from the standpoint of evolutionary success. This metaphor catalyzed important developments in evolutionary psychology, kin selection theory, and sociobiology. It clarified how complex behaviors like altruism could arise from gene-level strategies. But its anthropomorphic language also led to public misunderstanding. Many took it as a claim about human nature rather than gene behavior — a confusion Dawkins later tried to dispel. Still, the metaphor remains empirically anchored. It functions as a modeling device within an established theoretical framework. Unlike Eros, it does not imply metaphysical forces or cosmic intentions. It is a metaphor with boundaries. Wilber's Eros: From Metaphor to MetaphysicsKen Wilber's use of Eros as a metaphor for evolution operates in an entirely different register. In his Integral Theory, Eros is the inner drive of the cosmos toward greater complexity, consciousness, and spiritual realization. It is “Spirit-in-action,” the unfolding of divine purpose through the material world. Wilber sometimes treats Eros as a metaphor for creative emergence, but more often he treats it as an ontological principle — a metaphysical necessity. It is not a heuristic device but a worldview in itself. As such, it violates the constraints of scientific metaphor: it is not testable, falsifiable, or operationally defined. From Lakoff's perspective, Eros is not just a metaphor used to describe a theory; it is a metaphor that structures the theory itself. It reshapes what counts as evidence, explanation, and even evolution. It smuggles teleology back into biology under the guise of spiritual insight. Why Eros Is a Misleading Metaphor for EvolutionEven when read charitably, Eros is a problematic metaphor for evolution for several reasons: 1. It reintroduces teleology. 2. It anthropomorphizes at a cosmic scale. 3. It mystifies the process. 4. It confuses metaphor with metaphysics. Could Eros Work in a Spiritual View of the World?Yes — and here is the nuance. While Eros is ill-suited as a metaphor within scientific explanation, it may serve as a powerful metaphor in a spiritual, poetic, or philosophical worldview. If one conceives of the cosmos not merely as a causal mechanism but as an unfolding mystery, then Eros — understood as a metaphor for longing, emergence, or transcendence — can be deeply evocative. In this sense, it functions like Blake's vision of the universe, not Darwin's. The key is not to confuse registers. Metaphors can work differently in different domains. What illuminates in myth may obfuscate in science. The danger arises when one imports a metaphor across these boundaries without acknowledging the shift in epistemic context. Frank Visser's Longstanding CritiqueThis very point has been made consistently — and courageously — by Frank Visser, founder of Integral World and one of Ken Wilber's most informed critics. For over two decades, Visser has challenged Wilber's habit of blending spiritual metaphors with scientific claims, especially his invocation of Eros as a driving force behind evolution. Visser has argued that Wilber routinely violates the norms of scientific discourse by introducing metaphysical assumptions as if they were explanatory models. Where science demands clarity about what is metaphor and what is mechanism, Wilber's discourse often clouds that distinction. Visser has shown how this leads to confusion rather than integration — a poetic metaphysics masquerading as evolutionary theory. His critiques stand as a reminder that genuine integration of science and spirituality must respect the boundaries and methods of both domains. Conclusion: Metaphor, Model, and MeaningLakoff reminds us that metaphors are not merely linguistic but conceptual — they shape how we understand reality. In science, this gives them both power and peril. The best metaphors open up inquiry without closing down critique. They make the strange familiar without making it sacred. Darwin's natural selection and tree of life remain enduring metaphors because they clarified, rather than glorified, the evolutionary process. Dawkins' “selfish gene” metaphor, despite public confusion, largely stayed within this tradition. Wilber's Eros departs from it. It is not an aid to scientific explanation but a re-enchantment of it — one that blurs boundaries between fact and faith. Still, in a spiritual context, Eros might serve a different role — as a metaphor for the human experience of mystery, emergence, and longing. The essential task is to know where metaphor ends and method begins — a line Wilber too often crosses, as Frank Visser has rigorously and persistently pointed out.

|