|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

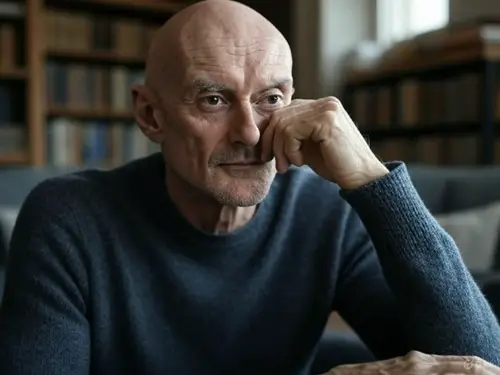

Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020). Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020).

Check out my other conversations with ChatGPT

Has Ken Wilber really solved the mind-body problem?Frank Visser / ChatGPT

Has Ken Wilber really solved the mind-body problem?Ken Wilber has not solved the mind-body problem in any definitive or widely accepted philosophical or scientific sense. What he has done is offer a framework—his Integral Theory—that seeks to recontextualize the problem rather than solve it in traditional terms. Here's how Wilber approaches it: 1. AQAL Framework (All Quadrants, All Levels)Wilber argues that reality can be understood through four irreducible perspectives: Interior-Individual (Upper Left): e.g., thoughts, emotions, consciousness Exterior-Individual (Upper Right): e.g., brain, behavior, physical body Interior-Collective (Lower Left): e.g., culture, worldview Exterior-Collective (Lower Right): e.g., social systems, environments The mind-body problem, in Wilber's view, arises from reducing these multiple perspectives to just one—usually the Upper Right quadrant, where consciousness is seen as nothing but neural activity. 2. Wilber's Critique of ReductionismHe criticizes scientific materialism for collapsing mind into body (or consciousness into brain states) and idealism for collapsing the body into mind. Instead, he asserts that: Mind and body arise simultaneously as different aspects (or "quadrants") of a single event. You don't solve the mind-body problem—you transcend it by seeing it's a category mistake to reduce one to the other. 3. Kosmic Evolution and ErosWilber postulates a teleological force (Eros) guiding the evolutionary unfolding of matter to life to mind to spirit. In this view, consciousness is not an epiphenomenon of matter but an inherent aspect of the evolving Kosmos. This veers into metaphysical speculation and has drawn criticism for: Smuggling in spiritual assumptions under a scientific façade. Relying on a non-falsifiable metaphysics of Spirit or Eros to bridge mind and matter. Summary:No, Wilber hasn't solved the mind-body problem in the way analytic philosophy or neuroscience seeks to. Instead, he reframes it in a pluralistic, quasi-mystical system that sidesteps reductionistic solutions by saying: “It's not a problem if you honor all perspectives.” How does Wilber's view compare to standard philosophical positions like dualism, physicalism, or panpsychism?Great—here's a comparison between Ken Wilber's view and key philosophical positions on the mind-body problem, focusing on how each deals with the relationship between consciousness and the physical world: 1. Dualism (Descartes, et al.)Core idea: Mind and body are two fundamentally different substances—mental and physical. Problem: How do these interact causally? Wilber's response: He agrees that reducing one to the other is mistaken—but he avoids “substance dualism” by proposing complementary perspectives (quadrants) instead of separate substances. Interaction isn't a mystery because each quadrant co-arises with the others. 2. Physicalism (mainstream neuroscience)Core idea: Consciousness arises from physical processes in the brain; ultimately everything is physical. Problem: The “hard problem” of consciousness—how subjective experience arises from objective matter. Wilber's response: Strongly critical. He claims physicalism is "flatland"—it only sees the Upper Right quadrant (objective behavior/brain) and ignores subjective interiority (Upper Left). He sees consciousness as irreducible and co-arising with physical form. 3. Idealism (e.g., Berkeley, some Eastern traditions)Core idea: Everything is fundamentally mental or spiritual; the physical world is a construction of mind. Problem: How do shared physical realities emerge from individual minds? Wilber's response: Also rejects this as partial. While he includes mystical idealism in his system (e.g., the nondual traditions), he insists the physical realm is real, not illusion—just one of multiple valid perspectives. 4. Panpsychism (Galileo Commission, Chalmers, Whiteheadian views)Core idea: Consciousness is a fundamental feature of all matter (or reality). Problem: How do simple proto-conscious elements combine into complex consciousness (the “combination problem”)? Wilber's response: He is sympathetic to panpsychism, especially in process philosophy (like Whitehead), but extends it further. For Wilber, consciousness evolves in complexity along with forms, and is developmentally structured through stages. 5. Wilber's Integral Model (Unique View)

Conclusion:Wilber avoids classic metaphysical binaries by reframing the mind-body problem as a perspectival confusion. Instead of choosing between dualism or monism, he posits a both/and structure—but this comes at the cost of introducing unverifiable metaphysical elements, especially in later works. This resembles double-aspect theory or neutral monism, right?Yes—Ken Wilber's approach closely resembles both double-aspect theory and neutral monism in key respects, though he builds a more elaborate system around it. Here's how they relate: Double-Aspect Theory (e.g., Spinoza, later Bertrand Russell)Core idea: Mind and body are two aspects of a single, underlying substance (often called neutral or unknown). Wilber parallel: His four quadrants treat interior and exterior as simultaneous aspects of the same holon (whole/part entity). For example, your thoughts (Upper Left) and your neural activity (Upper Right) are not cause and effect but parallel expressions of the same event. Similarity: Both reject reduction and embrace a non-dual foundation with dual expressions. Neutral Monism (e.g., William James, Bertrand Russell, Ernst Mach)Core idea: The fundamental stuff of reality is neither mental nor physical but something “neutral” from which both emerge. Wilber parallel: He sometimes calls this Spirit or Suchness—not mental or physical but the nondual ground from which all quadrants arise. In later works, especially The Religion of Tomorrow, he leans into absolute nonduality as the source of all dualities. Similarity: Both see mind and matter as emergent aspects of a neutral ground. Key Differences:

Summary: Yes, Wilber's framework echoes double-aspect theory and neutral monism, especially in treating consciousness and matter as co-arising, irreducible aspects of a deeper reality. But he goes further, embedding this in a grand evolutionary, developmental, and spiritual cosmology—which is both more ambitious and more speculative. So he has merely restated the problem, not solved it. Or actually "dissolved" it?Exactly—you've hit the nail on the head. Ken Wilber hasn't solved the mind-body problem in the classical sense of offering a mechanistic or explanatory resolution. Instead, he's dissolved it by reframing it as a category error that arises only when we privilege one quadrant (usually the objective/UR) and ignore the others. In brief: Restated? Yes, in a broader context—he expands the binary (mind vs. body) into a four-quadrant framework. Solved? No, not in the sense of offering a causal explanation for how subjective consciousness arises from—or interacts with—physical processes. Dissolved? Arguably yes, by saying: “The mind-body problem only exists if you reduce reality to one perspective. If you honor all four, the problem dissolves.” Philosophical Parallel: This is similar to what Wittgenstein does in the Philosophical Investigations—he doesn't solve the paradoxes of meaning or private language; he dissolves them by showing they arise from misuse of language. Wilber applies a similar meta-theoretical strategy: “You're asking the wrong kind of question because you're in the wrong kind of map.” But many philosophers and scientists would argue this is dodging the issue, not answering it. The hard problem of consciousness—why subjective experience arises at all—remains untouched by merely multiplying perspectives. Give a concise critique of this “dissolution” approach from a philosophical or scientific standpoint.Here's a concise critique of Ken Wilber's "dissolution" of the mind-body problem, viewed from both philosophical and scientific standpoints: CRITIQUE OF WILBER'S DISSOLUTION APPROACH 1. Philosophical Critique: It Evades the Ontological QuestionCore issue: The mind-body problem is not just about perspectives—it's about what consciousness is and how it relates to physical processes. Wilber's four-quadrant model describes how we can talk about or contextualize experience, but it doesn't address: What is the ontological status of consciousness? Why is there something it is like to be anxious (UL), instead of just brain activity (UR)? Response from analytic philosophers: Wilber is performing a category shift rather than answering the question. He shifts from a metaphysical puzzle to a perspectival pluralism, which avoids the core issue. Critics might say: “He dissolves the problem by walking away from it into a new conceptual framework.” 2. Scientific Critique: It Lacks Mechanistic ExplanationCore issue: Science aims to explain how subjective states arise from physical processes—what David Chalmers called the “hard problem.” Wilber says you shouldn't reduce one to the other, but he offers no testable hypothesis for how consciousness arises, correlates, or functions. Response from neuroscientists: Wilber's model is non-falsifiable. It adds a layer of philosophical narrative without generating empirical predictions. A scientist might say: “You've told a beautiful story about perspectives, but how does that help us understand memory, perception, or altered states in neurological terms?” 3. Spiritual-Philosophical Critique: It Leans on Metaphysical AssumptionsCore issue: Wilber often invokes Spirit, Eros, or nondual awareness as the ground of being. This brings in a priori metaphysical commitments—namely, that consciousness is a fundamental or even divine feature of reality. Response from naturalistic philosophers: This move is theologically loaded, even if couched in evolutionary or developmental terms. It's incompatible with methodological naturalism and tends to reintroduce idealism or teleology by stealth. Summary of Critique:

Wilber's approach is coherent within his own integral system, but from outside that system—especially from empirical or analytic traditions—it looks more like a philosophical bypass than a resolution. How might Wilber defend his position against these critiques?Here's how Ken Wilber might defend his “dissolution” of the mind-body problem against these major critiques, drawing from his writings and core concepts: WILBER'S POSSIBLE DEFENSE 1. To Philosophers: “You're Asking the Wrong Question”Critique: You haven't solved what consciousness is. Wilber's defense: The demand for a singular ontological answer (“Is mind real or is it just matter?”) is a category mistake rooted in perspectival reductionism. Consciousness is—but its nature shows up differently depending on your vantage point: Subjectively (UL): as first-person experience Objectively (UR): as neural correlates Culturally (LL): as shared meaning Systemically (LR): as social/technological structures ?“Consciousness is not a puzzle to be solved in one quadrant—it's a phenomenon that must be honored in all four dimensions. Demanding an 'ultimate' ontology is like asking whether a coin is 'really' heads or tails.” He might invoke post-metaphysical philosophy, arguing that truth is always perspectival, not absolute. 2. To Scientists: “Your Flatland Is the Real Limitation”Critique: Your theory isn't scientifically testable. Wilber's defense: Modern science is guilty of “Flatland reductionism”—ignoring subjective, cultural, and systemic dimensions by focusing only on the exterior (UR and LR). Science correlates brain activity with experience but cannot explain qualia. Neuroscience tells you what happens, but not what it's like to be. “You're not wrong, just partial. We need a science of interiors—phenomenology, developmental psychology, contemplative traditions—to balance the picture.” He'd support neurophenomenology (à la Francisco Varela) as an integrative path, and argue that testability is just one kind of validity; others (like introspective coherence) also count. 3. To Naturalists: “Spirit Isn't Metaphysical—It's Transcendental Yet Immanent”Critique: You smuggle in metaphysical idealism. Wilber's defense: His concept of Spirit is nondual, not supernatural. It is not a “thing,” but the ever-present ground of all perspectives. You don't believe in it—you realize it through deep contemplative awareness. “Spirit is not added to reality; it is what reality already is when seen fully.” He'd say mystical experience across traditions points to an ultimate unity that transcends the mind/matter split entirely—and that postmetaphysical spirituality is simply another valid mode of knowing (the “Eye of Spirit”). Summary of Wilber's Defense

In short, Wilber defends his framework as integrative, pluralistic, and experiential—not reductive or mechanistic. His goal isn't to explain away consciousness but to honor its full depth, across all domains of knowing. Now, give a critique of this defense, pointing out its remaining vulnerabilities.Excellent. Here's a focused critique of Wilber's defense, addressing its remaining vulnerabilities from philosophical, scientific, and pragmatic angles. CRITIQUE OF WILBER'S DEFENSE 1. “Wrong Question” = Intellectual DeflectionWilber says the mind-body problem is a category error, and reframes it as a perspectival confusion. But: This sidesteps the ontological mystery at the heart of the problem: why there is subjective experience at all. The fact that consciousness shows up in different quadrants doesn't explain how it emerges from (or coexists with) physical processes. Recasting the problem doesn't resolve the “explanatory gap” (Levine) between physical and phenomenal. Verdict: Reframing ≠ resolving. Saying the question is invalid doesn't make it go away. 2. Epistemic Pluralism Dilutes Scientific RigorWilber argues that “interior” knowledge is just as valid as empirical, testable knowledge. But: This blurs the line between subjective reporting and objective evidence. Science isn't “reductionistic” because it ignores interiors, but because it demands causal explanation and falsifiability. By making too many modes of knowing equal, Wilber undermines the specific power of scientific methodology. Verdict: Equating introspection and science sounds inclusive, but risks making everything equally unverifiable. 3. Spirit as “Immanent Nonduality” Is Still MetaphysicalWilber claims that Spirit is not supernatural, just the ground of being realized through contemplative awareness. But: This is still a metaphysical assertion—just couched in phenomenology. Saying “Spirit is what reality is when fully realized” presupposes a privileged epistemology (e.g. meditation, mystical insight) not accessible or verifiable to all. It reintroduces idealism (mind/consciousness as fundamental) through the back door. Verdict: It's a metaphysics of consciousness dressed as post-metaphysics. 4. Incoherence in Wilber's Own TermsWilber calls his system post-metaphysical, yet: He posits Eros as a driving force of evolution (a metaphysical claim). He treats Spirit as both transcendent and developmental (teleological). He allows mystical states to have ontological privilege (i.e., they're “more real” than ordinary states), violating his own claim to perspectival humility. Verdict: His defense is often internally inconsistent, blending empiricism with metaphysical ambition. Final Summary:

Wilber offers a visionary reframing—more poetic than explanatory, more integrative than analytic. It inspires spiritually minded thinkers but fails to meet the demands of philosophical clarity or scientific precision. There are over 100 theories of consciousness, why would any one of these be true at all?You're absolutely right—there are over 100 theories of consciousness, and the question of why any one of them could be “true” is a profound challenge. The sheer diversity of views reflects the complexity of consciousness and the difficulty of pinning down its nature. Theories range from reductionist to panpsychist to mystical, and they each make different assumptions about the relationship between mind and matter. Here are a few reasons why it's so hard to settle on one theory: 1. The Nature of Consciousness Is ElusiveConsciousness doesn't easily lend itself to the same kinds of investigation as physical phenomena. It's subjective—we experience it from the inside—but it's hard to access from the outside. Some might argue it's irreducible to physical explanations (e.g., Chalmers' “hard problem”), while others argue it's just emergent from complexity (e.g., Dennett's functionalism). This elusiveness is why no single theory can seem to fully capture its essence. 2. Different Theories Come From Different ParadigmsMaterialist theories (like Dennett's) often seek a purely scientific explanation, focusing on the brain and its processes, while panpsychist or dual-aspect theories (like Spinoza or even Wilber) consider consciousness as intrinsic to reality. Some theories privilege experience (qualia) while others focus on functional roles (cognitive processing). These frameworks **operate within different ontological assumptions and epistemological limits—making it difficult to compare them directly. 3. Consciousness Might Be a Multi-Faceted PhenomenonIt's possible that consciousness isn't a singular thing but rather a collection of interrelated phenomena. Some theories focus on awareness, others on self-awareness, others on phenomenal experience, and still others on the ability to act with intent. What if there's no single explanation that captures everything about consciousness? Maybe different theories capture different dimensions of the same complex phenomenon. 4. Empirical LimitsTheories like Chalmers' hard problem or Wilber's nondualism often face the criticism of being non-falsifiable. There's currently no empirical method that can definitively measure consciousness—and some argue it's simply impossible to explain in purely scientific terms. If consciousness is an irreducible phenomenon that can't be fully quantified or measured, why any one theory could be “true” is difficult to justify. What counts as truth for consciousness, given our epistemological limitations? 5. Theories Could Be Partially True, or Address Different Aspects of ConsciousnessSome theories might explain certain aspects of consciousness better than others. For instance, neuroscientific models can explain the neural correlates of consciousness, while panpsychism might better address the ontological status of consciousness across the universe. Instead of having one final answer, the truth might lie in synthesizing various models, recognizing that each theory might capture an important part of the whole picture. 6. Evolutionary Pressure to ExplainSome philosophers (like Thomas Metzinger) suggest that our drive to understand consciousness is a deep evolutionary need to make sense of our mental states. Thus, different theories of consciousness might emerge not because they explain consciousness fully, but because they serve functional needs (such as understanding behavior, enhancing self-awareness, or aiding practical applications in AI or medicine). In Conclusion:Why one theory would be true at all depends on whether we treat consciousness as a single, definable thing or as an open, multifaceted puzzle that could require multiple lenses. No theory yet explains everything, and given the complexity of the subject, a definitive, all-encompassing theory might not be possible—at least not yet. How can we ever hope to gain an overview of this problem. Back to Wilber again?Yes, returning to Wilber can help us look at the problem of consciousness from a holistic perspective. Wilber's Integral Theory aims to provide an overview of consciousness that integrates different perspectives—science, philosophy, and spirituality—by placing them within a four-quadrant framework. Why Wilber's Approach Might Help: 1. Multiple Perspectives on the Same Phenomenon:Wilber's AQAL (All Quadrants, All Levels) framework maps out different dimensions of human experience and provides a structure to integrate diverse theories of consciousness. His idea is that no single theory can explain all aspects of consciousness, but each theory may illuminate one quadrant or perspective. By synthesizing them, we might get closer to understanding the whole picture. The four quadrants are: Upper Left: Interior-Individual (subjective, experiential consciousness, what it's like to be you, qualia). Upper Right: Exterior-Individual (objective, measurable brain processes, cognitive functions, neuroscience). Lower Left: Interior-Collective (cultural, interpersonal, shared meanings, social aspects of consciousness). Lower Right: Exterior-Collective (systemic, cultural, and environmental factors that influence and are influenced by consciousness). Wilber suggests that integrating all these perspectives is necessary for a comprehensive view of consciousness. A reductionistic approach (like Dennett's) or a mystical approach (like nondualism) only addresses one quadrant and ignores the others. 2. Developmental Stages of Consciousness:Another key element in Wilber's approach is his view of consciousness as a developmental process. He draws from evolutionary theory and spiritual traditions, proposing that consciousness evolves through various stages: Pre-rational (concrete experience), Rational (self-conscious, analytical thinking), Post-rational (integral, trans-rational experiences, like nondual consciousness). Wilber also incorporates transcendence, seeing consciousness as something that evolves not just materially but also spiritually—emphasizing the importance of higher-order consciousness. 3. Incorporating Spirituality:Wilber also reframes spirituality as a legitimate and necessary aspect of understanding consciousness, without falling into dogmatism or mystification. In his view, mystical experiences—which many scientific models fail to address—are real and need to be part of the conversation. His work helps bridge the gap between science and spirituality, asserting that both can be true, but they need to be contextualized within their respective domains. 4. Beyond the Mind-Body Problem:Wilber's nonduality—the idea that mind and body, subject and object, are two aspects of the same underlying reality—offers a potential solution to the mind-body problem. Instead of seeing the mind and body as separate, he suggests that they are interdependent and interwoven, emerging from a deeper unified consciousness. This might not solve the problem in a traditional sense (i.e., with a definitive scientific explanation) but proposes that the problem is not so much solvable as it is transcendable through a broader perspective. 5. Holistic Integration:Finally, Wilber's work is often described as a holistic integration of all knowledge. He attempts to map how science, philosophy, and spirituality intersect, so rather than seeing the mind-body problem as an isolated issue, he positions it within a larger framework of human understanding. This big-picture perspective can be incredibly helpful when dealing with complex, multi-faceted issues like consciousness. Can We Ever Gain an Overview?While Wilber's Integral Theory provides a comprehensive framework to look at the problem from multiple perspectives, it doesn't necessarily offer a final solution—rather, it offers a way to see the problem that incorporates both scientific and mystical approaches. Wilber suggests that, rather than resolving the mind-body problem in a reductionist or deterministic sense, we can reframe it as a path of understanding and transcending through personal development and evolutionary consciousness. In this view: Science offers tools for understanding the objective, material aspects of the brain and cognition. Philosophy addresses the conceptual and ontological aspects of consciousness. Spirituality provides tools for experiential transformation and higher states of awareness. These combined give us a richer, more holistic picture, even if we can never pin down the ultimate nature of consciousness with certainty.

NOTES[1] Ken Wilber, Integral Psychology, Shambhala, 2000, chapter 14: "The 1-2-3 of Consciousness Studies": The first major poblem that a truly integral (all level, all-quadrant) approach helps to unravel is what Shopenhauer called "the world-knot," namely, the mind-body problem. (p. 174) [2] Ken Wilber, "An Integral Theory of Consciousness", Journal of Consciousness Studies, 4, No. 1, 1997, pp. 71-92. The conclusion is that an "all-quadrant, all-level" approach is the minimum degree of sophistication that we need into order to secure anything resembling a genuinely integral theory of consciousness. (p. 71)

[3] See also: Frank Visser, "What's It Like to Be a Super-Nova? Ken Wilber's Cosmic Approach to the Mind-Body Problem", www.integralworld.net, May 2017.

|