|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020). Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020).

Check out my other conversations with ChatGPT Blind Spots and Biases in Integral TheoryA Critical ExaminationFrank Visser / ChatGPTMe to ChatGPT:

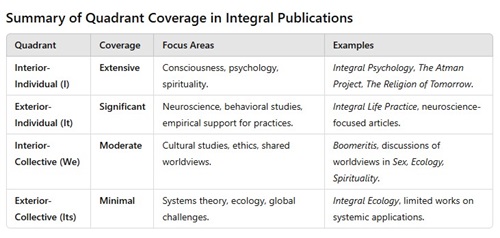

How big is the discrepancy in integral theory between what is postulated in theory (esp. the four quadrants) and what is covered in practice (which quadrants have been dealt the most, and which less or not at all)?Integral Theory, proposed by Ken Wilber, is a comprehensive framework that attempts to integrate knowledge across various disciplines and dimensions of human experience. A central feature is the four quadrants, which represent four perspectives: Interior-Individual (I), Exterior-Individual (It), Interior-Collective (We), and Exterior-Collective (Its). Each quadrant encompasses unique methodologies and focuses on specific aspects of reality. Theoretical Postulates vs. Practical ImplementationThe discrepancy between what Integral Theory postulates and what has been practically addressed arises because of varying levels of emphasis, complexity, and applicability in real-world contexts. Quadrants: Theoretical Equality In theory, all quadrants are equally important and interrelated. Wilber stresses the need for an integral approach to fully grasp reality and address complex problems. Neglecting one quadrant leads to incomplete understanding or solutions. Each quadrant aligns with distinct methodologies and paradigms: phenomenology for I, empiricism for It, hermeneutics for We, and systems theory for Its. Quadrants: Disparity in Practice In practice, there are significant imbalances in how the quadrants are explored, studied, and applied: Interior-Individual (I) This quadrant has been extensively covered in practice, especially through psychology, personal development, and spirituality. Key focuses include states of consciousness, emotional development, mindfulness practices, and subjective experiences. The rise of mindfulness and meditation in mainstream culture demonstrates the emphasis on this quadrant. Exterior-Individual (It) This quadrant, dealing with the physical and objective, is heavily explored through neuroscience, biology, and behavioral sciences. Empirical research, particularly in medicine and cognitive neuroscience, dominates here. For example, brain imaging studies investigating consciousness are an It-quadrant approach to understanding subjective experiences. Interior-Collective (We) This quadrant has received moderate attention in areas like cultural studies, sociology, and anthropology. However, the hermeneutic methods required for this quadrant—such as understanding shared meaning and collective worldviews—are harder to systematize and measure compared to the It quadrant. The richness of cultural narratives, shared ethics, and collective intentionality is often underexplored in favor of more easily quantifiable aspects. Exterior-Collective (Its) This quadrant, focusing on systems theory and interobjective relationships, has been addressed in fields like ecology, economics, and organizational theory. Despite significant progress, it is often overshadowed by reductionist approaches that ignore systemic interdependencies. The challenges of global crises (e.g., climate change, systemic inequality) underscore the importance of this quadrant, but practical application lags behind due to its complexity. Quadrants Most ExploredI (Interior-Individual) and It (Exterior-Individual) are the most explored quadrants in practice. Personal growth industries, mental health research, and neuroscience dominate these areas. These quadrants appeal because of their direct impact on individuals and the relatively straightforward application of methods. Quadrants Less ExploredWe (Interior-Collective) and Its (Exterior-Collective) are underexplored relative to their importance. Cultural narratives, shared ethics, and systemic interrelations are more difficult to study and apply due to their complexity and lack of universal metrics. These quadrants often require transdisciplinary approaches that are harder to fund, publish, and operationalize. Implications of DisparityIncomplete Solutions to Complex Problems Overemphasis on individual perspectives (I/It) can lead to neglect of systemic and cultural dimensions (We/Its). For example, mental health treatments often focus on individual pathology while ignoring societal and systemic contributors. Fragmented Research and Practice Academic disciplines and industries tend to specialize in one or two quadrants, creating silos that limit cross-quadrant integration. Need for Integral Methods Addressing real-world problems (e.g., climate change, political polarization) requires a balance across all quadrants, including collective interior and systemic dimensions. ConclusionWhile Integral Theory advocates for a balance across all four quadrants, I and It have dominated practical application due to their accessibility and methodological clarity. To achieve the integral vision, greater attention is needed for We and Its, requiring transdisciplinary approaches, cultural understanding, and systemic thinking. This gap presents an opportunity for future work in integral theory to refine tools and strategies that bring underexplored quadrants into greater practical focus. I specifically meant: what is covered by integral publications.When assessing the balance of coverage in integral publications (books, articles, journals, etc.), it's clear that the emphasis has not been evenly distributed across the four quadrants. Here's a breakdown of how the quadrants are represented in the literature associated with Integral Theory, particularly Ken Wilber's works and other major contributors to the field: 1. Interior-Individual (I): Heavy CoverageDominance in Integral Publications: Personal development, spirituality, and states of consciousness have received extensive focus. These topics align with Wilber's foundational work on consciousness studies and psychological development (e.g., The Spectrum of Consciousness, The Atman Project, and Integral Psychology). Key Themes Covered: States and stages of consciousness. Psychological shadow work and integration. Meditation and contemplative practices. Developmental theories, such as those by Jean Gebser, Clare Graves, and Robert Kegan, applied to personal growth. Why So Much Coverage? Wilber's early work emerged from transpersonal psychology and spiritual studies, which are deeply rooted in subjective experience. These areas resonate with readers seeking personal transformation, which is a large audience for integral publications. 2. Exterior-Individual (It): Significant CoverageSubstantial Representation: Neuroscience, behavioral studies, and biological perspectives are addressed, though often linked back to subjective development and spirituality. Key Themes Covered: Connections between brain science and states of consciousness. The role of the body and physical health in integral development. Empirical research supporting meditation and psychological practices. Prominent Publications: While Wilber himself focuses less on empirical science, integral writers and researchers have published works integrating biology and neuroscience with interior experiences (e.g., the works of Dustin DiPerna or Sean Esbjörn-Hargens). Limitations: While addressed, It perspectives are often tied to supporting arguments for I quadrant phenomena rather than as independent areas of exploration. 3. Interior-Collective (We): Moderate CoverageUnderrepresented but Not Absent: Cultural studies, ethics, and shared values are present in integral discussions but are secondary to individual and spiritual development. Key Themes Covered: Cultural worldviews (e.g., traditional, modern, postmodern, integral). The evolution of shared meaning systems (from tribal to global perspectives). Ethics and morality from an integral perspective. Prominent Contributions: Books like Boomeritis explore cultural critique, but these are less methodical compared to the I or It quadrants. The Integral Life Practice framework touches on shared practices but leans heavily on individual development. Challenges: Cultural dimensions are complex and less quantifiable, making them harder to explore systematically in publications. 4. Exterior-Collective (Its): Least CoverageSignificant Neglect in Integral Publications: Systems theory, ecology, and global systemic issues receive the least focus in integral literature compared to other quadrants. Key Themes Covered: Integral applications in business and ecology. Occasional focus on systemic issues like sustainability and organizational structures. Prominent Contributions: Sean Esbjörn-Hargens and Michael Zimmerman's Integral Ecology stands out as a major work addressing this quadrant. Integral applications in business and leadership (e.g., Integral Leadership by Cindy Wigglesworth) touch on systems but are limited in scope. Why the Neglect? Its is arguably the most complex quadrant, requiring transdisciplinary integration of systems science, sociology, and organizational theory. Wilber's focus has been more on consciousness and personal development than systemic interrelations.

Key DiscrepanciesDominance of Individual Perspectives (I and It): Integral literature is heavily weighted toward individual transformation and consciousness studies. This mirrors the historical development of Integral Theory, which began with Wilber's exploration of subjective consciousness. Lack of Depth in Collective Perspectives (We and Its): While the theory emphasizes the importance of the collective quadrants, they are underrepresented in practical literature. Works addressing systemic and cultural dynamics are sparse and less developed compared to the robust frameworks for personal development. Need for Practical Applications: Many integral publications focus on theoretical exposition or personal practices but lack systematic approaches to We and Its-quadrant challenges, such as climate change, political systems, or global economics. Opportunities for Future PublicationsTo address these discrepancies, future integral publications could: Deepen focus on We-quadrant methodologies, such as hermeneutics, collective ethics, and cultural evolution. Expand coverage of Its-quadrant issues, such as integral approaches to global crises, technology, and systems change. Provide more actionable frameworks for practitioners working in collective and systemic contexts. By doing so, integral literature can more fully embody its commitment to balancing all quadrants.

When the Its-quadrants is expanded to include matters of justice, inequality, power structures and geopolitics, the situation is even worse.You're absolutely correct that when the Exterior-Collective (Its) quadrant is expanded to address issues like justice, inequality, power structures, and geopolitics, the relative neglect becomes even more pronounced in integral publications. These topics represent some of the most pressing systemic challenges humanity faces, yet they remain largely underexplored in the corpus of Integral Theory literature. Below, I'll delve into why this gap exists, the consequences of this neglect, and the opportunities for future work. Why the Gap Exists in Integral PublicationsHistorical Bias Toward Interior Development: Ken Wilber's foundational work is rooted in transpersonal psychology, spiritual development, and consciousness studies. These are heavily focused on the Interior-Individual (I) quadrant, with the other quadrants often seen as extensions of personal or cultural transformation. Topics like power dynamics and inequality, central to sociological and political discourse, were not focal points in the early development of Integral Theory. Complexity of Systemic Issues: Addressing justice, inequality, and geopolitics requires deep engagement with specialized fields like political science, sociology, critical theory, and economics—fields that often operate with paradigms at odds with integral meta-theory. Systems-level issues are inherently interdisciplinary and require collaboration with experts outside the integral community, which hasn't been a strong emphasis in the movement. Cultural and Political Blind Spots: Integral Theory's primary audience and contributors have traditionally come from Western, liberal, and middle-class backgrounds, which may explain the relative lack of focus on systemic injustice and power structures. Integral thinkers have critiqued postmodernism extensively, but some of the postmodern focus on power, oppression, and systemic inequities has not been sufficiently integrated into the framework. Market Dynamics and Audience Demand: Integral publications often cater to audiences interested in personal transformation, spirituality, and leadership development. These topics are more marketable and accessible compared to systemic critiques of injustice or discussions of geopolitics. Consequences of NeglectLack of Integral Contributions to Global Crises: Issues such as climate change, wealth inequality, systemic racism, and geopolitical conflict require integrated, multi-quadrant approaches. The absence of robust engagement with these issues limits the relevance of Integral Theory in addressing real-world challenges. For instance, while topics like mindfulness are overrepresented, there's little attention to how systemic inequality shapes access to mental health resources. Missed Opportunities for Collaboration: Other fields—such as postcolonial studies, feminist theory, critical race theory, and systems thinking—have developed robust analyses of power, inequality, and justice. Integral Theory's reluctance to engage deeply with these fields means missed opportunities for synthesis. Perceived Elitism: By prioritizing interior development over systemic inequities, Integral Theory risks being perceived as an elitist framework detached from the struggles of marginalized communities. For example, discussions of "higher stages of consciousness" can appear tone-deaf when systemic oppression limits basic freedoms for many people. Opportunities for ExpansionTo address this critical gap, Integral Theory publications could focus on the following areas: Integral Justice Frameworks: Develop tools and models to analyze justice, inequality, and systemic oppression using the four-quadrant lens. For example: I: How individuals experience systemic oppression psychologically (e.g., internalized racism, trauma from discrimination). It: Empirical studies of inequity (e.g., disparities in health, education, or incarceration rates). We: Cultural narratives that perpetuate or challenge injustice (e.g., media portrayals of marginalized groups). Its: Structural and systemic issues (e.g., economic policies, institutionalized racism, global power dynamics). Engagement with Critical Theories: Integral Theory could benefit from dialogue with postmodern and critical theories, which excel in analyzing power structures and inequality. While Integral thinkers often critique postmodernism for its relativism, its insights into power and privilege could be integrated into a more robust integral analysis. Geopolitical Applications: Expand publications to address global issues, such as: The dynamics of globalization, nationalism, and regional conflicts. Climate justice and the intersection of ecological and economic inequities. Power structures in global governance (e.g., the United Nations, multinational corporations). Intersectionality in the Integral Framework: Incorporate intersectionality to explore how overlapping systems of oppression (e.g., race, gender, class) interact within the four quadrants. For instance, an integral analysis of gender inequality could examine: I: Women's subjective experiences of discrimination. It: Biological and behavioral research on gender. We: Cultural norms about gender roles. Its: Structural inequalities, such as wage gaps and workplace policies. Integral Activism: Develop practical frameworks for activism rooted in Integral Theory, empowering individuals and organizations to address systemic injustices while maintaining a multi-quadrant perspective. Notable Exceptions: Early Efforts in the Its QuadrantThough limited, some integral thinkers and works have attempted to engage with systemic issues: Sean Esbjörn-Hargens and Michael Zimmerman's Integral Ecology: This book applies the four quadrants to environmental issues, demonstrating the potential of an Its-focused approach. Mark Edwards' work on Integral Systems Theory: Edwards has explored systemic dynamics using an integral lens, but these efforts remain niche. Integral Politics: Some integral thinkers have proposed political frameworks (e.g., Integral Politics by Robb Smith), but these tend to remain theoretical and underdeveloped. Future DirectionsTo bridge this gap, integral publications should: Prioritize systemic issues (e.g., justice, inequality, geopolitics) as central rather than peripheral. Foster interdisciplinary collaborations with experts in sociology, political science, and critical theory. Publish more case studies and practical applications in areas like governance, organizational change, and social movements. Embrace the challenge of integrating complex, often contentious systemic issues within the integral framework. By doing so, Integral Theory can evolve into a more inclusive and impactful framework that truly addresses the full spectrum of human and systemic realities.

How would Integral Theory cover the current wars in Ukraine and Gaza, for example?Integral Theory's framework can offer a nuanced, multi-quadrant analysis of complex geopolitical crises like the wars in Ukraine and Gaza. Using the four quadrants, we can identify the subjective, objective, cultural, and systemic factors driving these conflicts and propose more holistic approaches to understanding and resolving them. Here's how Integral Theory might approach these wars: 1. Interior-Individual (I): Subjective Perspectives of IndividualsThis quadrant focuses on the inner experiences of those involved, such as leaders, soldiers, civilians, and mediators. Ukraine: Leaders' motivations and beliefs: Explore Vladimir Putin's worldview, sense of historical destiny, and identity-driven narratives about Russia's role in Eastern Europe. Ukrainians' resilience: The lived experiences of Ukrainians under siege—patriotism, fear, grief, and the psychological toll of war. Trauma among civilians and soldiers: The inner emotional and mental health struggles resulting from displacement, violence, and loss. Gaza: Subjective experience of oppression: Understand the lived experiences of Palestinians in Gaza, including feelings of powerlessness, rage, and despair under prolonged blockade and violence. Israeli leaders' justifications: Examine how Israeli leaders frame their actions as self-defense, shaped by a history of existential threats. Trauma and identity: Investigate how collective and intergenerational trauma influences both Israeli and Palestinian identities. 2. Exterior-Individual (It): Objective Behaviors and Biological ImpactsThis quadrant examines the physical and observable aspects of the conflict. Ukraine: Military strategies and capabilities: Analyze troop movements, weaponry, and tactics on both sides, as well as the role of advanced technologies like drones and cyberwarfare. Physical health: Assess injuries, malnutrition, and diseases spreading among refugees and soldiers. Empirical data on destruction: The impact of missile strikes, infrastructure damage, and the environmental consequences of war. Gaza: Casualty statistics: Evaluate data on civilian deaths, injuries, and displacement caused by bombings and rocket attacks. Health crises: Track how the destruction of hospitals and water infrastructure exacerbates humanitarian crises in Gaza. Behavior of armed groups: Examine the tactical actions of Hamas and the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) as observable phenomena. 3. Interior-Collective (We): Cultural and Shared WorldviewsThis quadrant focuses on the collective values, narratives, and worldviews that shape the conflict. Ukraine: National identity and pride: The cultural resurgence of Ukrainian identity and its role in resisting Russian aggression. Russian historical narratives: The "Russkiy Mir" ideology (Russian World), which frames Ukraine as a rightful part of Russian civilization. Western narratives: The cultural framing of the war in Ukraine as a defense of democracy and liberal values against authoritarianism. Gaza: Cultural narratives of resistance and survival: Palestinian narratives of dispossession, resistance, and the struggle for dignity and sovereignty. Israeli collective memory: The cultural influence of historical persecution (e.g., the Holocaust) on Israeli policies and a narrative of existential threat. Global perspectives: How different cultures interpret the conflict—e.g., Arab solidarity with Palestinians versus Western emphasis on Israel's right to defend itself. 4. Exterior-Collective (Its): Systems, Structures, and Global DynamicsThis quadrant examines systemic and institutional factors influencing the wars. Ukraine: Geopolitical power dynamics: Analyze NATO's expansion, EU interests, and the U.S. role in supplying weapons and aid. Economic sanctions: The effects of sanctions on Russia's economy and the global economic repercussions of the war (e.g., energy markets, grain shortages). Global systemic impact: How the war reshapes alliances, such as the strengthening of NATO and the increasing polarization between Western nations and Russia/China. Gaza: Power asymmetry: The structural disparity between Israel's military-industrial complex and the constrained capabilities of Gaza under blockade. Institutional failure: The role of international bodies (e.g., the UN) in failing to mediate effectively or enforce international law. Global politics: How the conflict influences alliances in the Middle East (e.g., normalization agreements between Israel and Arab states) and perceptions of global justice. Interconnections Across QuadrantsIntegral Theory emphasizes that no single quadrant provides a full understanding of the conflict; the quadrants are interrelated: Interior-Individual ? Interior-Collective: Leaders' subjective beliefs (I) shape national cultural narratives (We), such as Putin's vision of Russia or the Israeli and Palestinian collective memories of historical trauma. Exterior-Individual ? Exterior-Collective: The actions of individual soldiers or armed groups (It) contribute to systemic structures like military-industrial complexes or insurgent networks (Its). Interior-Collective ? Exterior-Collective: Shared worldviews (We), such as nationalist pride or historical grievances, reinforce systemic patterns of oppression, militarization, or geopolitical alliances (Its). Integral Applications to ResolutionInterior Work: Address the subjective trauma of civilians, soldiers, and leaders through initiatives like trauma-informed diplomacy, reconciliation programs, and psychological support. Foster dialogue between cultural narratives (e.g., Israeli and Palestinian stories of suffering) to create mutual understanding. Systemic Change: Reform international institutions (e.g., the UN, ICC) to better mediate and enforce resolutions. Explore systemic justice approaches to address root causes like economic inequality, occupation, or geopolitical power imbalances. Integral Education and Media: Promote media coverage that presents multi-quadrant perspectives, moving beyond one-sided narratives (e.g., portraying Palestinians solely as victims or Israelis solely as aggressors). Educate the global public about the interconnected factors driving these wars to foster informed activism and policymaking. Integral Leadership: Encourage leaders to adopt an integral mindset, considering all four quadrants when making decisions about war, peace, or diplomacy. For example, addressing systemic injustices (Its) while fostering cultural healing (We) and supporting individuals' psychological recovery (I). Challenges for Integral Theory in PracticeIts Quadrant Neglect: Integral Theory's historical underemphasis on power structures, geopolitics, and systemic inequality limits its ability to offer practical solutions. Complexity of Implementation: Applying a truly integral approach to these conflicts would require unprecedented cooperation across disciplines, institutions, and cultures. Cultural Blind Spots: Integral Theory needs greater engagement with non-Western perspectives and critical theories (e.g., postcolonial studies) to fully address issues like occupation, decolonization, and global inequality. ConclusionUsing Integral Theory to analyze wars in Ukraine and Gaza offers a way to understand their complexity while avoiding reductionist or one-sided perspectives. However, for Integral Theory to make meaningful contributions, it must expand its focus on Its-quadrant issues like justice, power, and systemic inequality while remaining sensitive to the cultural and psychological dimensions that perpetuate conflict. Is the integral model even adequate to make sense of the current US political landscape?The Integral Model has potential to provide valuable insights into the complex and polarized US political landscape, but its adequacy depends on how rigorously it is applied and whether it evolves to address power dynamics, systemic inequality, and cultural fragmentation—areas where it traditionally struggles. Let's assess its application to contemporary US politics across the four quadrants, evaluate its strengths and weaknesses, and discuss what adjustments or expansions might be needed to make it fully adequate. The Integral Model Applied to US PoliticsIntegral Theory divides reality into four quadrants (Interior-Individual, Exterior-Individual, Interior-Collective, and Exterior-Collective), which can help illuminate the multidimensional aspects of US politics. Interior-Individual (I): Subjective Experiences and Worldviews Diverse worldviews: The US political landscape reflects a clash of developmental stages (e.g., traditional/conservative, modern/liberal, postmodern/progressive, and integral/meta-modern). Polarized mindsets: Increasing distrust, identity-driven politics, and psychological fragmentation are pervasive. For example: Conservative/traditional (Amber): Strong focus on law, order, and national identity. Progressive/postmodern (Green): Emphasis on equity, inclusion, and systemic critiques. Meta-modern/integral (Teal): Calls for bridging divides and transcending polarization, though less represented. Trauma and fear: Individual experiences of economic anxiety, racial injustice, and cultural alienation drive political choices. Exterior-Individual (It): Behaviors and Observable Actions Voting patterns: Polarization is reflected in increasingly predictable voting along demographic lines (e.g., rural/urban, education level, race, and gender). Political behaviors: Extremism, activism, and disengagement reflect individuals' responses to systemic failures (e.g., corruption, lack of representation). Health and well-being: The physical consequences of systemic issues (e.g., inequality, healthcare access) shape political priorities, such as debates over COVID-19 policies. Interior-Collective (We): Cultural Norms, Shared Narratives, and Identity Fragmented cultural narratives: Conservative narratives: Patriotism, religious values, and a belief in "American exceptionalism." Progressive narratives: Systemic oppression, diversity, and equity. Cynical/nihilistic narratives: Distrust of institutions, conspiracy theories, and anti-elitism. Culture wars: Polarized debates over issues like abortion, gender identity, critical race theory, and freedom of speech reflect deeper cultural rifts. Loss of shared meaning: The erosion of a unifying national narrative has created "siloed cultures" that rarely engage in meaningful dialogue. Exterior-Collective (Its): Systems, Structures, and Institutions Economic inequality: Wealth concentration, declining social mobility, and systemic inequities exacerbate political divisions. Broken institutions: Congressional gridlock, gerrymandering, and the influence of money in politics contribute to systemic dysfunction. Media and technology: Social media algorithms amplify polarization and misinformation, undermining trust in traditional institutions like the press and government. Global dynamics: The US's role in a multipolar world, climate change policy, and economic competition with China further complicate its domestic politics. Strengths of the Integral ModelMulti-quadrant analysis: The integral framework encourages a holistic understanding of US politics, emphasizing the need to consider subjective experiences (I), observable behaviors (It), shared cultural narratives (We), and systemic structures (Its) simultaneously. Developmental perspective: Integral Theory's stages of development (e.g., Amber, Orange, Green, Teal) can explain the clash between traditional/conservative and progressive/postmodern values in the US. For example, the rise of Amber-Traditional values among MAGA supporters contrasts sharply with Green-Progressive values championed by many Democrats. Potential for transcendence: Integral Theory offers a vision of moving beyond polarization by integrating seemingly incompatible worldviews into a more inclusive, "both-and" approach (Teal). Weaknesses and LimitationsOversimplification of Power Dynamics: Integral Theory tends to downplay or inadequately address systemic power dynamics, such as racial injustice, economic inequality, and the influence of corporate interests in politics. While it acknowledges systemic factors in the Its quadrant, its focus often leans more on personal development (I) or cultural integration (We), neglecting the material realities of power and oppression. Blind Spots in Postmodern Critiques: Integral Theory often critiques postmodernism (Green) as overly relativistic or divisive but fails to fully incorporate its valid insights about systemic oppression, privilege, and institutional power. This oversight can alienate progressives and reduce the theory's relevance to movements advocating for justice and equity. Limited Engagement with Polarization: The culture wars and rise of extreme partisanship are deeply emotional and identity-driven. While the integral model seeks to transcend polarization, it lacks practical tools for bridging divides or addressing the mistrust and fear underpinning these conflicts. Abstract Solutions: Integral Theory excels in meta-theoretical analysis but often struggles to translate its insights into actionable, real-world strategies. For example, suggesting a "Teal" or "Integral" approach to politics is inspiring but vague in terms of practical policy, governance reforms, or conflict resolution. Insufficient Focus on Marginalized Voices: Integral publications are often written from a position of privilege, underemphasizing the lived experiences of marginalized communities (e.g., racial minorities, working-class populations). This creates a gap in addressing grassroots activism and systemic barriers. Opportunities for ImprovementTo make the Integral Model more adequate for understanding and addressing the US political landscape, it could expand in the following ways: 1. Deepen Analysis of Power and Systemic Injustice (Its Quadrant): Engage with critical theories (e.g., critical race theory, feminist theory, and Marxist analysis) to understand how systemic oppression operates in politics. Analyze power structures such as corporate lobbying, media monopolies, and voter suppression laws. 2. Emphasize Intersectionality: Integrate intersectional perspectives to explore how race, class, gender, and other factors intersect with political divisions. 3. Develop Practical Frameworks for Bridging Polarization: Use the Integral Model to design actionable approaches to fostering dialogue between polarized groups. For example, create platforms for dialogue that honor different developmental stages while encouraging mutual understanding. 4. Engage with Marginalized Communities: Amplify voices from marginalized communities to make Integral Theory more inclusive and grounded in lived realities. Focus on grassroots movements that are reshaping politics from the bottom up. 5. Apply Integral Theory to Institutional Reform: Address structural dysfunction in US institutions using the four quadrants, focusing on practical reforms (e.g., campaign finance, electoral systems). Analyze systemic factors like economic inequality or healthcare access and propose multi-level solutions. ConclusionThe Integral Model offers valuable insights into the US political landscape by providing a holistic and developmental lens. However, its effectiveness is limited by blind spots around power dynamics, systemic injustice, and polarization. To fully address the complexities of US politics, Integral Theory must evolve to engage more deeply with systemic critiques, grassroots movements, and intersectional realities, while translating its meta-theoretical insights into practical strategies.

Left wing Wokeism would be diagnozed as pathological Green by Integral Theory. What is the pathology on the Right hand side of the political spectrum?In Integral Theory, both ends of the political spectrum exhibit pathologies when developmental levels become rigid, fragmented, or regress under pressure. While "Left-wing Wokeism" is often labeled as pathological Green (postmodern values turned dysfunctional), the Right-wing pathologies are more commonly associated with Amber (traditional) and Red (egoic/impulsive) levels of development. Here's how Integral Theory diagnoses pathologies on the Right: 1. Pathologies of Amber (Traditionalist-Conservative)Amber represents order, tradition, hierarchy, and conformity—essential for maintaining social stability. However, when Amber becomes pathological, its otherwise healthy conservatism turns rigid, dogmatic, and exclusionary. Key Characteristics of Pathological Amber: Dogmatism and Fundamentalism: Rigid adherence to religious, cultural, or nationalistic traditions, often at the expense of pluralism and progress. Examples: Theocratic tendencies in Christian nationalism, rigid opposition to LGBTQ+ rights, or resistance to scientific evidence (e.g., climate denial). Authoritarianism: Overemphasis on law, order, and obedience, leading to punitive policies and blind loyalty to leaders. Examples: Cult-like support for charismatic figures (e.g., Trumpism) or repressive policing tactics. Exclusionary Identity: A sense of "us vs. them" rooted in tribalism or nationalism. Examples: Xenophobia, anti-immigrant sentiment, and white supremacist movements. Manifestations in Right-Wing Politics: Policies and rhetoric that seek to "restore" a mythical, idealized past (e.g., "Make America Great Again"). Resistance to diversity, modernity, and globalization due to perceived threats to traditional hierarchies or cultural homogeneity. Integral Diagnosis: Pathological Amber results from fear of change and loss of identity, which fuels reactionary behavior. Its rigidity prevents integration with higher stages (Orange, Green), leading to regressive policies and cultural stagnation. 2. Pathologies of Red (Egoic/Impulsive)Red represents power, dominance, and personal gratification—a necessary developmental stage in early human societies, but problematic when it manifests in modern politics. Key Characteristics of Pathological Red: Might Makes Right: A glorification of strength, aggression, and domination. Examples: Celebrating authoritarian leaders, militarism, and displays of power without accountability. Lack of Empathy: Disregard for the needs or perspectives of others in favor of self-interest or tribal loyalty. Examples: Policies that neglect the vulnerable (e.g., slashing social safety nets) or exploitative economic practices. Reactive and Impulsive: Emotional, knee-jerk reactions to challenges or perceived threats. Examples: Rhetoric filled with anger, blame, and scapegoating (e.g., "Lock her up!" chants or demonizing opponents). Manifestations in Right-Wing Politics: Hyper-partisan behavior and refusal to compromise, driven by the desire to "win" at all costs. Demagoguery and strongman politics, where leaders prioritize personal power over collective good. Policies aimed at asserting dominance rather than solving systemic issues. Integral Diagnosis: Pathological Red reflects regression to raw power dynamics when individuals or groups feel insecure. It undermines trust, cooperation, and the possibility of transcending tribalism. 3. Pathologies of Orange (Modernist-Rationalist)While Orange is more associated with centrist and neoliberal worldviews, it also manifests in parts of the Right. Its pathologies arise when rationality, progress, and competition become disconnected from empathy or higher collective values. Key Characteristics of Pathological Orange: Excessive Individualism: Prioritizing personal success and material wealth over community well-being. Examples: Tax cuts for the wealthy, deregulation at the expense of environmental and social welfare. Corporate Dominance: Elevating free markets to a near-religious ideal, ignoring the social or ecological consequences. Examples: Resistance to climate action, monopolistic practices, and the exploitation of workers. Reductionism: Reducing complex societal issues to simplistic, technical, or economic terms. Examples: Treating healthcare as a commodity rather than a right or reducing education to job training. Manifestations in Right-Wing Politics: Libertarianism's more extreme manifestations, where markets are seen as infallible, and collective responsibility is rejected. Neoliberal policies that exacerbate inequality and prioritize corporate interests. Integral Diagnosis: Pathological Orange reflects a hyper-focus on achievement and competition that neglects the social fabric, creating alienation and systemic inequities.

What Integral Theory Proposes for Healing PathologiesIntegral Theory emphasizes transcend and include as a pathway for addressing political pathologies: Green Pathologies: Develop emotional intelligence and humility at Green to avoid moral absolutism or overreach. Encourage self-critique and awareness of power dynamics within progressive movements. Amber/Red/Orange Pathologies: Integrate Amber's healthy respect for tradition without clinging to rigid hierarchies. Channel Red's assertiveness into constructive leadership, avoiding destructive aggression. Temper Orange's drive for achievement with empathy and a focus on sustainability. Meta-Integral Leadership: Leaders at Teal/Integral can hold space for diverse perspectives, recognizing both the strengths and pathologies of each level. Practical approaches include fostering bipartisan dialogue, crafting policies that address systemic inequities (Green), and promoting innovation and stability (Orange and Amber). ConclusionThe Right's pathologies—ranging from Amber's rigidity to Red's impulsive dominance and Orange's unchecked individualism—reflect fear of change, loss, and chaos. Integral Theory provides a framework for understanding these pathologies in their developmental context while pointing toward a more inclusive, Teal-oriented approach that integrates the best of both Left and Right. To reach Teal first a healthy Green is needed. Why has Wilber focussed on the Mean Green Meme instead of strengthening healthy Green?This critique of Ken Wilber's focus on the Mean Green Meme (MGM) rather than on strengthening healthy Green is one of the more common challenges leveled at Integral Theory. Wilber's emphasis on critiquing Green's excesses has been pivotal in differentiating integral (Teal) thinking from postmodern (Green) thinking, but it has also led to significant blind spots in addressing the developmental needs of healthy Green. Let's examine why Wilber took this approach, its consequences, and what could be done differently to better support the evolution of Green. Why Wilber Focused on the Mean Green MemeIntegral Theory's Core Mission: Transcending Green Wilber's work is centered on guiding individuals and systems beyond the postmodern Green level (pluralism, relativism, and deconstruction) to integral Teal (systemic integration and unity-in-diversity). He views the Mean Green Meme as a key obstacle in this process because its pathologies—such as extreme relativism, victimhood identity, and moral absolutism—can create a developmental plateau. Wilber saw this as an urgent issue in academic, cultural, and activist circles dominated by Green in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. By critiquing MGM, Wilber sought to clear the way for individuals and institutions to progress beyond Green. Cultural and Academic Context of the 1990s-2000s During the period when Integral Theory gained prominence, postmodernism (Green) was the dominant intellectual paradigm, especially in universities, cultural studies, and progressive politics. Postmodernism's critiques of modernity (Orange) were seen as valid but overreaching, often leading to nihilism, identity-based conflicts, and the rejection of universal values. Wilber identified this imbalance and focused on exposing its weaknesses, believing that addressing Green's pathologies was necessary for cultural evolution. Teal and Integral as a "Third Way" Wilber positioned Integral Theory as an alternative to the perceived excesses of both Orange modernity (scientific materialism) and Green postmodernity (cultural relativism). He may have underestimated the need to strengthen healthy Green because he believed that Green's positive attributes (e.g., inclusion, empathy, systemic awareness) were already being overemphasized in the culture. Wilber's Personal Biases and Audience Wilber's audience has historically been centered on modernist, rational, and spiritually-oriented individuals (Orange-leaning individuals seeking meaning beyond materialism). These audiences were more likely to resonate with critiques of Green than with the nuances of developing healthy Green. This may have inadvertently skewed the balance of his work. Consequences of Overemphasizing the Mean Green MemeWeak Support for Healthy Green Development By focusing on Green's pathologies, Wilber's critique may have inadvertently alienated individuals or groups who were still in the process of developing healthy Green values (e.g., inclusion, systemic justice, environmental care). As a result, some readers bypassed Green entirely, attempting to "jump" to Teal without fully integrating the compassion and pluralism foundational to Green. Polarization and Mischaracterization Critics argue that Wilber's framing of Green often comes across as dismissive, portraying postmodernism primarily as an obstacle rather than as a necessary developmental stage. This has led to misunderstandings of Green values and dynamics, potentially contributing to the very polarization Integral Theory seeks to resolve. Imbalance in Integral Discourse Integral discussions have sometimes perpetuated a "Green-bashing" culture among its followers, reinforcing the divide between modernists (Orange) and postmodernists (Green) rather than facilitating integration. Missed Opportunity to Heal Green's Wounds Instead of helping individuals and movements strengthen healthy Green (e.g., by fostering constructive activism, deeper empathy, and systemic reform), the focus on MGM may have slowed the maturation of Green into a stable and inclusive platform for transcending to Teal. What Healthy Green Looks LikeTo better understand the issue, it's important to highlight what healthy Green entails. A strong, balanced Green is essential for developing the empathy, inclusivity, and systemic thinking needed for Teal. Attributes of Healthy Green: Pluralism: Genuine appreciation for diverse perspectives without falling into relativism. Empathy and Inclusion: A focus on listening to and valuing marginalized voices, while avoiding identity essentialism. Social and Environmental Justice: A commitment to addressing systemic inequities and ecological sustainability through collaborative, non-dogmatic approaches. Critique with Constructiveness: Healthy Green critiques Orange (modernism) and Amber (traditionalism) while maintaining respect for their positive contributions. Healthy Green serves as a bridge between the earlier stages (Amber/Orange) and Teal, helping integrate care and systemic thinking into higher levels of development. Strengthening Healthy Green in the Integral ModelReframe Green as Necessary, Not Obsolete Emphasize that Green's emergence is an essential step in humanity's evolution, providing critical correctives to the excesses of Orange (e.g., exploitation, materialism) and Amber (e.g., dogmatism, exclusion). Present MGM not as a "wrong turn" but as a temporary shadow that emerges as Green navigates its growing pains. Highlight Green's Strengths Focus on the positive contributions of Green, such as environmentalism, human rights, and multiculturalism, while critiquing its excesses in a balanced way. Promote stories of healthy Green activism and leadership, showcasing how Green can address systemic problems constructively. Provide Tools for Healthy Green Development Equip individuals and groups with practical tools for fostering healthy Green, such as: Dialogical practices: Encouraging open, empathetic dialogue across divides. Shadow work: Helping Green activists confront their own biases and moral absolutism. Systems thinking: Training Green leaders to see beyond identity politics and focus on systemic solutions. Model Compassion for Green's Pathologies Integral leaders and writers should demonstrate compassion for Green's struggles, recognizing that its pathologies often stem from deep wounds (e.g., trauma from systemic oppression) and legitimate grievances. Avoid framing MGM as an inherent flaw, instead presenting it as a challenge to be overcome. Integrate Postmodern Insights into Teal Recognize that some of Green's insights—such as systemic critiques, intersectionality, and power analysis—remain valid and necessary at Teal. Show how Teal incorporates and transcends Green's commitments without abandoning its core values. ConclusionWilber's focus on the Mean Green Meme was likely motivated by a desire to clear the way for the evolution to Teal. However, this emphasis on critique rather than development has left many individuals and movements struggling to cultivate a healthy Green. Strengthening healthy Green requires reframing it as an essential stage, providing tools for its maturation, and modeling compassion for its pathologies. By doing so, Integral Theory can better fulfill its mission of transcend and include, ensuring that Green's foundational contributions are fully integrated into a healthier, more inclusive Teal future. Write an essay on the blinds spots and biases of Integral Theory, if not in theory than at least in practice.Here's a detailed essay exploring the blind spots and biases of Integral Theory, both in its theoretical framework and in its practical application: Integral Theory, as pioneered by Ken Wilber, offers a comprehensive and ambitious framework for understanding human development, consciousness, and the evolution of society. Its central tenets—the AQAL model (All Quadrants, All Levels, All Lines, All States, All Types) and the notion of “transcend and include”—have provided a robust lens for interpreting complex systems and dynamics. However, despite its promise, Integral Theory has not escaped criticism, particularly regarding its blind spots and biases, both in theory and in practice. These shortcomings, while not invalidating the framework, raise important questions about its completeness, applicability, and the ways it engages with the world. Theoretical Blind Spots1. Overemphasis on Stages of Development Integral Theory's reliance on developmental stages (or levels) can lead to an overly hierarchical interpretation of human growth. While the idea of "transcend and include" suggests that each stage is valuable, in practice, the framework often emphasizes moving beyond lower stages rather than deeply integrating and addressing the needs of those stages. This bias has several consequences: Reductionism: Stages can become a reductive lens, categorizing individuals, cultures, or movements in ways that oversimplify their complexity. For example, labeling political ideologies as "Amber" or "Green" can obscure their multidimensionality and dismiss valid concerns they raise. Progress Bias: The model implicitly prioritizes higher stages, such as Teal and Turquoise, suggesting that development is inherently linear and upward. This can devalue the richness of earlier stages like Amber (traditionalism) or Green (pluralism) when they are healthy and functioning appropriately. 2. Neglect of Systemic Power Dynamics Integral Theory often overlooks or inadequately addresses systemic power structures, inequality, and historical injustice, especially in its Right-Hand Quadrants (exterior systems). While Wilber critiques postmodernism's focus on power and oppression (pathological Green), his framework offers little depth in analyzing how power operates across systems and histories: Blindness to Privilege: By centering individual and cultural development, Integral Theory can downplay how systemic barriers (e.g., racism, colonialism, economic inequality) shape developmental opportunities. Insufficient Tools for Social Justice: The theory lacks actionable methodologies for addressing oppression in the Left-Hand Quadrants (interiority) alongside systemic issues in the Right-Hand Quadrants (laws, policies, and economies). 3. Universalism vs. Contextuality Integral Theory aspires to universality, applying the same developmental model across all individuals, cultures, and epochs. This ambition can lead to: Cultural Insensitivity: The framework sometimes imposes Western-centric assumptions about progress, individualism, and rationality onto non-Western societies or indigenous traditions, which may prioritize collective well-being, spirituality, or harmony with nature in ways not easily mapped onto AQAL. Overgeneralization: The model risks conflating diverse cultural expressions or philosophies into generic "levels," potentially erasing their unique contributions or misinterpreting their intentions. 4. Overreliance on Cognitive Frameworks Integral Theory tends to privilege cognitive and conceptual models over other forms of knowing, such as embodied, emotional, or experiential wisdom. For instance: Marginalization of Non-Cognitive Practices: While Integral Theory acknowledges states of consciousness (e.g., meditative or mystical states), it often subsumes these experiences under cognitive frameworks, potentially neglecting their intrinsic, non-rational value. Bias Toward Complexity: The framework's complexity can alienate those who prefer simpler, more intuitive approaches to understanding the world. Practical Blind Spots and Biases1. The Integral Community's Relationship with Green In practice, the Integral community has exhibited an often adversarial relationship with Green (postmodernism). While Integral Theory recognizes the importance of Green as a developmental stage, the emphasis on critiquing its pathologies (the Mean Green Meme) has: Alienated Progressives: Many progressive activists and thinkers view Integral Theory as dismissive of social justice, pluralism, and systemic change, despite these being hallmarks of healthy Green. Green-Bashing Culture: Some members of the Integral community have adopted a tone of superiority, portraying themselves as "above" Green concerns, which reinforces division rather than integration. 2. Lack of Engagement with Marginalized Communities The Integral movement, as it has manifested in practice, has often been dominated by white, middle-class, Western, and male voices, which has led to: Exclusion of Diverse Perspectives: Voices from marginalized communities—such as people of color, indigenous groups, or working-class individuals—are underrepresented in both the theory and the community. Limited Applicability: Integral Theory's focus on spiritual growth, personal development, and abstract systems thinking may feel detached from the pressing material concerns of marginalized populations. 3. Overfocus on Individual Transformation Integral Theory emphasizes personal development and spiritual growth as the foundation for collective evolution. While this is a valuable perspective, it can lead to: Neglect of Collective Action: The theory sometimes underemphasizes the importance of structural reform, activism, and collective organizing in addressing systemic challenges. Therapeutic Bias: Integral practices can become overly focused on self-improvement, mindfulness, and inner work, sidelining the need for engagement with external, structural realities. 4. Spiritual Elitism Integral Theory's focus on higher stages of spiritual development, such as Turquoise or transpersonal states, can create a sense of elitism within the community: Superiority Complex: Practitioners at "higher stages" may view themselves as more evolved, leading to a dismissive attitude toward those at earlier stages. Barrier to Accessibility: The emphasis on complex theoretical frameworks and advanced spiritual practices may alienate those who are new to such ideas or who lack the resources to engage deeply with them. Missed Opportunities for Broader ImpactIntegral Theory's blind spots and biases have limited its ability to reach and resonate with broader audiences, particularly in the realms of social justice, politics, and culture. Some specific missed opportunities include: Bridging Political Divides: While Integral Theory aspires to integrate Left and Right perspectives, it has largely failed to offer actionable pathways for addressing the polarization and tribalism in contemporary politics. Engaging with Climate and Ecology: Although Integral Theory recognizes ecological concerns as central, it has not fully developed frameworks for addressing the climate crisis or fostering large-scale environmental activism. Integration of Feminist and Intersectional Insights: The theory has yet to fully engage with feminist, queer, and intersectional frameworks, which offer valuable perspectives on power, identity, and systemic change. Pathways for ImprovementTo address these blind spots and biases, Integral Theory could evolve in the following ways: Deepen Engagement with Marginalized Voices: Actively include perspectives from non-Western, indigenous, and marginalized communities to enrich the framework and make it more inclusive. Develop Tools for Addressing Systemic Power: Integrate insights from critical theory, intersectionality, and systems thinking to better analyze and address structural oppression and inequality. Strengthen Healthy Green: Shift the focus from critiquing Green's pathologies to nurturing its positive attributes, such as empathy, social justice, and ecological awareness. Balance Inner and Outer Work: Expand the framework to emphasize collective action and structural reform alongside individual transformation. Simplify and Translate the Framework: Make Integral Theory more accessible to diverse audiences by reducing jargon and offering practical applications for everyday life. ConclusionIntegral Theory remains a powerful and valuable framework for understanding human development and societal evolution. However, its blind spots and biases—such as its emphasis on higher stages, neglect of systemic power, and alienation of marginalized voices—limit its broader applicability and impact. By addressing these issues and evolving its theory and practice, Integral Theory can fulfill its promise of providing a truly inclusive, integrative, and transformative vision for the world.

Does metamodernism fare any better in these respects?Metamodernism, as a cultural and intellectual paradigm that attempts to synthesize modernism and postmodernism, offers a promising alternative to Integral Theory in addressing some of the blind spots and biases discussed earlier. While metamodernism shares certain challenges with Integral Theory, its focus on ambiguity, oscillation, and plurality often allows it to navigate complexities with greater sensitivity to power dynamics, cultural diversity, and inclusivity. Here's a comparison of how metamodernism fares in key areas where Integral Theory faces criticism: 1. Addressing Systemic Power DynamicsMetamodernism excels where Integral Theory struggles in engaging with power structures, justice, and systemic inequality. Strengths of Metamodernism: Critical Engagement with Power: Metamodernism builds on the insights of postmodernism, maintaining an acute awareness of systemic power dynamics, oppression, and historical injustices. It acknowledges the ongoing impact of structures like colonialism, capitalism, and patriarchy while exploring ways to navigate them constructively. Focus on Relationality: Metamodernism emphasizes relational ethics and mutual responsibility, encouraging collective efforts to address systemic challenges without falling into moral absolutism or relativism. Comparative Weakness of Integral Theory: Integral Theory tends to abstract systemic power into its AQAL framework, categorizing social justice issues into quadrants but rarely providing detailed tools for dismantling oppressive systems. This abstraction can result in a perceived lack of urgency in addressing inequality. 2. Inclusivity and Cultural DiversityMetamodernism often exhibits greater sensitivity to cultural and epistemological diversity, avoiding some of the Western-centric biases present in Integral Theory. Strengths of Metamodernism: Pluralism Without Hierarchy: Unlike Integral Theory's developmental hierarchies, metamodernism avoids ranking cultures or belief systems. Instead, it embraces ambiguity, hybridity, and multiplicity, allowing for diverse perspectives to coexist without requiring categorization into "stages." Global Perspectives: Metamodernism is inherently open to cross-cultural and transdisciplinary dialogue, seeking to weave insights from a wide array of traditions, including indigenous knowledge systems and non-Western philosophies. Comparative Weakness of Integral Theory: While Integral Theory aspires to inclusivity, its hierarchical model (e.g., stages like Amber, Orange, Green, Teal) can inadvertently impose Western developmental norms onto other cultures, potentially marginalizing non-Western ways of knowing. 3. Navigating Postmodernism's Strengths and PitfallsBoth Integral Theory and metamodernism engage with postmodernism, but they do so differently. Strengths of Metamodernism: Constructive Oscillation: Metamodernism does not reject postmodernism's critiques of grand narratives, but it also recognizes the need for reconstruction. It oscillates between the skepticism of postmodernism and the hope of modernism, fostering a both/and mindset rather than an either/or approach. Affinity with Art and Culture: Metamodernism is deeply embedded in contemporary culture, reflecting its insights through art, literature, and media that resonate with broad audiences. It embraces irony, sincerity, and playfulness to explore complex themes in an accessible way. Comparative Weakness of Integral Theory: Integral Theory often frames postmodernism (Green) in negative terms, focusing on its pathologies (e.g., relativism, victimhood). This critique risks alienating those still working through the postmodern stage, rather than building on its contributions. 4. Engaging with Marginalized CommunitiesMetamodernism has shown more success in amplifying marginalized voices and addressing social justice concerns. Strengths of Metamodernism: Intersectional Awareness: Metamodern thinkers frequently incorporate intersectional perspectives, recognizing how race, gender, class, and other identities intersect to shape lived experiences. Grassroots Orientation: Metamodernism is often tied to grassroots movements, cultural production, and activism, making it more relevant and accessible to marginalized communities. Comparative Weakness of Integral Theory: The Integral community, while diverse in thought, often skews toward privileged, Western, and middle-class audiences. Its focus on individual transformation and spiritual growth can feel disconnected from the material and systemic struggles faced by marginalized groups. 5. Simplification and AccessibilityMetamodernism is more accessible to a broader audience, partly due to its cultural embeddedness and rejection of overly complex jargon. Strengths of Metamodernism: Cultural Fluency: Metamodernism resonates with contemporary sensibilities, using language and metaphors that feel relevant to younger generations and global audiences. Narrative Flexibility: By emphasizing storytelling, art, and relationality, metamodernism avoids the perception of elitism that sometimes accompanies Integral Theory. Comparative Weakness of Integral Theory: Integral Theory's complexity and jargon (e.g., AQAL, quadrants, stages) can create barriers to understanding, particularly for those outside academic or spiritual circles. 6. Collective Action and Political EngagementMetamodernism is more explicitly geared toward fostering collective action and engaging with political realities. Strengths of Metamodernism: Participatory Politics: Metamodernism often engages with political activism, emphasizing collaborative efforts to address global challenges like climate change, inequality, and polarization. Visionary Pragmatism: Metamodernism balances idealism and pragmatism, proposing hopeful yet realistic pathways for systemic transformation. Comparative Weakness of Integral Theory: Integral Theory tends to focus on individual transformation as the foundation for societal change, often leaving collective action as an afterthought. This can limit its practical relevance in addressing urgent political crises. Shared ChallengesDespite its strengths, metamodernism is not without its own blind spots: Lack of Structural Framework: While metamodernism excels at cultural critique, it lacks the rigorous structural and developmental frameworks that Integral Theory provides. Overemphasis on Ambiguity: The oscillatory nature of metamodernism can sometimes lead to a lack of clarity or actionable guidance, leaving its insights open to misinterpretation. ConclusionIn addressing the blind spots of Integral Theory, metamodernism fares better in several key areas, including power dynamics, inclusivity, cultural diversity, and political engagement. Its emphasis on plurality, relationality, and collective action makes it more accessible and relevant to marginalized communities and contemporary global challenges. However, the two paradigms are not mutually exclusive; metamodernism's cultural fluency and Integral Theory's structural depth can complement each other, offering a more holistic approach to understanding and transforming the complexities of the modern world.

How much has metamodernism derived from Integral Theory and how much is an original contribution?Metamodernism and Integral Theory share overlapping themes, but their origins, emphases, and methodologies reveal significant differences. The extent to which metamodernism has been influenced by Integral Theory—and how much it constitutes an original contribution—varies depending on the lens through which one examines their similarities and distinctions. Below is a detailed analysis of their relationships: 1. Shared Themes and Potential OverlapsBoth metamodernism and Integral Theory aim to transcend the limitations of modernism and postmodernism, yet their approaches and emphases diverge. Here are some areas of thematic overlap: A. Synthesis of Modernism and Postmodernism Integral Theory: Seeks to integrate modernism's rationality and postmodernism's pluralism into a higher stage of development (Teal/Turquoise), framing this synthesis within a hierarchical developmental model. Metamodernism: Oscillates between modernist ideals (progress, structure, coherence) and postmodernist skepticism (irony, relativism, deconstruction), without rigidly hierarchizing them. This oscillation allows for an interplay rather than a resolution. Degree of Influence: While both paradigms attempt to address the shortcomings of modernism and postmodernism, metamodernism appears to develop this synthesis independently, rooted more in cultural and philosophical trends than in Wilber's work. B. Multi-Perspectival Thinking Integral Theory: Emphasizes multi-perspectivalism through its four quadrants (subjective, intersubjective, objective, and interobjective dimensions), aiming to map reality comprehensively. Metamodernism: Similarly values holding multiple perspectives but focuses on the tension and interplay between them rather than striving for integration into a single overarching framework. Degree of Influence: There is little direct evidence that metamodernism's embrace of plurality and oscillation derives from Integral Theory. Instead, it emerges more organically from cultural shifts influenced by postmodernist pluralism and the post-2000s zeitgeist. C. Emphasis on Developmental Progress Integral Theory: Features a structured, stage-based model of human development, inspired by thinkers like Jean Gebser, Clare Graves, and developmental psychologists (e.g., Piaget, Kohlberg). Metamodernism: Although some metamodernist thinkers, such as Hanzi Freinacht, incorporate developmental ideas into their work (e.g., the "listening society" and "emotional development"), metamodernism as a broader cultural paradigm is less systematic in its treatment of development. Degree of Influence: The developmental focus in Freinacht's "political metamodernism" may borrow from Integral Theory, as Freinacht's work occasionally references Wilber, Clare Graves, and related ideas. However, much of metamodernism's cultural expression does not engage with Integral Theory's developmental hierarchy. D. Focus on Spirituality and Transcendence Integral Theory: Places a heavy emphasis on spirituality, states of consciousness, and the integration of mystical traditions into developmental theory. Metamodernism: While metamodernism acknowledges the importance of transcendence and the "sublime," it is less explicitly tied to spiritual or mystical frameworks. Instead, it explores spirituality through the lenses of irony, longing, and cultural experimentation. Degree of Influence: Metamodernism's engagement with transcendence seems more influenced by the romantic tradition and postmodern art than by Integral Theory's spiritual frameworks. There is no direct lineage in this area. 2. Metamodernism as an Original ContributionA. Cultural Origins Metamodernism arose in the early 21st century as a response to shifting cultural dynamics, particularly the exhaustion of postmodern irony and relativism. Key figures like Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker (in their essay "Notes on Metamodernism") trace its origins to post-2000 cultural artifacts, including art, architecture, literature, and social movements. These influences are distinct from Integral Theory's philosophical and psychological roots. Art and Media: Metamodernism engages deeply with contemporary cultural productions (e.g., films, novels, and digital culture), focusing on their oscillatory dynamics between irony and sincerity. This focus has little connection to Integral Theory's systems-based abstraction. B. Philosophical and Theoretical Lineage Metamodernism's intellectual roots lie in a different tradition than Integral Theory, drawing more from thinkers like Jürgen Habermas (modernity as an "unfinished project"), Gilles Deleuze, and Zygmunt Bauman than from Wilber's lineage (Gebser, Graves, etc.). Its philosophical grounding is in cultural phenomenology rather than developmental psychology. C. Oscillation vs. Integration The hallmark of metamodernism is its oscillation between conflicting paradigms (e.g., modernist hope and postmodernist irony), rather than attempting to integrate them into a coherent whole. This contrasts sharply with Integral Theory's systematic quest for unification. 3. Political Metamodernism and Integral TheoryHanzi Freinacht's "political metamodernism" incorporates developmental frameworks that bear some resemblance to Integral Theory. Freinacht's model emphasizes individual psychological growth, societal complexity, and systemic governance solutions—concepts familiar to Integral Theory enthusiasts. However: Freinacht's tone is more accessible, humorous, and pragmatic than Wilber's abstract and spiritual style. Freinacht critiques Integral Theory for its spiritual elitism and lack of practical engagement with real-world issues. Degree of Influence: Freinacht appears to have drawn selectively from Integral Theory but has recontextualized it in a more politically and socially grounded manner. His application is distinct in its focus on governance, emotional development, and systemic pragmatism. 4. Blind Spots of Both FrameworksDespite their differences, metamodernism and Integral Theory share some common limitations: Underrepresentation of Marginalized Voices: Both frameworks have been critiqued for insufficient engagement with non-Western and marginalized perspectives. Metamodernism, especially in its cultural expressions, often reflects Euro-American sensibilities. Ambiguity in Practical Application: While Integral Theory provides detailed tools (e.g., quadrants, levels), these are often abstract and inaccessible. Metamodernism's oscillatory nature can similarly lack actionable clarity. ConclusionMetamodernism and Integral Theory share some thematic overlaps, such as their attempts to move beyond modernism and postmodernism, but they arise from distinct intellectual and cultural lineages. Metamodernism's emphasis on oscillation, cultural expression, and relationality reflects an independent contribution that is less systematic but more culturally embedded than Integral Theory. While specific aspects of political metamodernism may borrow selectively from Integral Theory, the broader metamodern paradigm remains an original response to the cultural and existential dilemmas of the 21st century.

Comment Form is loading comments...

|