|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Scott F. Parker is a writer and editor whose books include Coffee - Philosophy for Everyone: Grounds for Debate and Running After Prefontaine: A Memoir. He has contributed chapters to Ultimate Lost and Philosophy, Football and Philosophy, Alice in Wonderland and Philosophy, Golf and Philosophy, and iPod and Philosophy. He is a regular contributor to Rain Taxi Review of Books. His writing has also appeared in Philosophy Now, Sport Literate, Fiction Writers Review, Epiphany, The Ink-Filled Page, and Oregon Humanities. In 2010 he published the print edition of Jeff Meyerhoff's Bald Ambition: A Critique of Ken Wilber's Theory of Everything. For more information, visit http://scottfparker.blogspot.com. Scott F. Parker is a writer and editor whose books include Coffee - Philosophy for Everyone: Grounds for Debate and Running After Prefontaine: A Memoir. He has contributed chapters to Ultimate Lost and Philosophy, Football and Philosophy, Alice in Wonderland and Philosophy, Golf and Philosophy, and iPod and Philosophy. He is a regular contributor to Rain Taxi Review of Books. His writing has also appeared in Philosophy Now, Sport Literate, Fiction Writers Review, Epiphany, The Ink-Filled Page, and Oregon Humanities. In 2010 he published the print edition of Jeff Meyerhoff's Bald Ambition: A Critique of Ken Wilber's Theory of Everything. For more information, visit http://scottfparker.blogspot.com.

The Case of WilberScott F. ParkerI'm speaking with myself, number one, because I have a very good brain and I've said a lot of things. — Donald Trump Preface

My greatest experience was a recovery. Wilber was merely one of my sicknesses. Not that I wish to be ungrateful to that sickness.

I have granted myself absolution. It is not with malice or regret that I praise Harris and others in this essay at the expense of Wilber. Amidst much denouncement is some affection. To turn my back on Wilber was for me a fate; to like anything at all again after that, a triumph. Perhaps nobody was more dangerously attached to—entangled with—Wilberizing; nobody prosthelytized for it more assuredly; nobody was luckier to be rid of it. A common enough story!—But the writer looks back so that he may face forward again. Self-overcoming for him is not just a pretty word; it is a kind of struggle. What does a writer demand of himself first and last? To see in all directions without forgetting where he's standing. To stand with one foot outside his circumstances. With what must he therefore engage in the hardest combat? With what binds him to his circumstances. Those binds must be escaped—busted! I am, no less than Wilber, a child of this time; that is, an egoist: but I comprehended this, I resisted it. The writer in me resisted. Nothing has preoccupied me more profoundly than the problem of selfhood. The fact of the consciousness of myself and others? No, the value of it. Once one has developed a keen eye for the symptoms of egoism, one understands so-called “independence,” too—one understands what is hiding under its most sacred names and value formulas: personal preference, voluntary relations, self-indulgence, individual rights. Private worlds negate reality. For such a task I required a special self-discipline: to take sides against everything sick in me, including Wilber, including my idiot-device, including most of contemporary “culture.” A profound estrangement, cold, sobering up—against everything that is of this time. To stand where one's own feet—to speak with those—to answer—to be accountable. For such a goal—what sacrifice wouldn't be fitting? what “self-overcoming”? what “self-denial”? My greatest experience was a recovery. Wilber was merely one of my sicknesses. Not that I wish to be ungrateful to that sickness. When in this essay I assert the proposition that Wilber is harmful, I wish no less to assert for whom he is nevertheless indispensable—for the writer. Others may be able to get along without Wilber; but the writer is not free to do without Wilber—in spirit if not in name. To properly diagnose his time, the writer needs to understand it. And confronted with the labyrinth of the contemporary self, where could he find a guide more initiated, a more eloquent prophet of the self, than Wilber? Through Wilber the present speaks most simply, concealing neither its good nor its evil, having forgotten all sense of shame. And conversely: one has almost completed an account of the value of what is contemporary once one has gained clarity about what is good and evil in Wilber. I understand perfectly when a young person today says: “I find Wilber's blustery self-satisfaction insufferable.” But I'd also understand a writer who would declare: “Wilber sums us up. Whether we like it or not, know it or not, we already are Wilberites.”

Sam Harris and and Ken Wilber

Yesterday I heard the masterpiece of Sam Harris's podcast for the—would you believe it?—hundredth time. Again I stayed there with tender devotion; again I did not run away. This triumph over impatience, over distraction, surprises me. Listening, one nearly becomes a “masterpiece” oneself. Really, every time I've heard Waking Up I seem to myself more of a writer, a better writer, than I generally consider myself: so patient do I become, so happy, so discerning. To sit two hours: the first stage of wisdom. May I say that the tone of Harris's podcast is almost the only one I can still enjoy? By contrast, Wilber's speech is arrogant, incurious, and flattering at the same time—thus it speaks directly to the contemporary soul—how harmful for me is this Wilberian tone! I call it noise. I step outside to breathe fresh air. My patience for it is gone. How did I ever tolerate such glibness? This podcast seems perfect to me not for what it says but for how it proceeds—carefully, logically, with self-awareness, and most importantly: curiously. “What is profound is compassionate; whatever is wise listens with tender ears”: first principle of my methodology. This philosophy is forceful. It is precise. It is dispassionate. It builds, connects, responds—it is alive. How is this achieved? Without the lie of outlandish claims, outlandish style. Finally, Harris's address treats its listener as intelligent, as if himself a philosopher—and is in this respect, too, the counterpart of Wilber, who is, whatever else he is, the most condescending philosopher in the world. (Wilber treats us as if—he says something so often—till one despairs—till one believes it.) Wilber is an elite self-advertiser. He knows that if we hear his spiel often enough it will eventually become easier for us to think through it than around it. Once more: I become a better human being when this Harris speaks to me. Also a better thinker, a better listener. Is it even possible to listen better? I actually bury my ears in these ideas to hear their sources. It seems to me I experience their genesis. And I never appreciate Harris more than when I disagree with him. (Wilber I never distrust more than when he says something that sounds right to me.) Has it been noticed that listening liberates the spirit?—especially this era when we never listen and constantly consume; the writer hates consumers—dead things. That listening gives wings to thought? That one becomes more of a writer the more one becomes a reader? The gray sky of abstraction illuminated as if by lightning; the light strong enough for the filigree of things; the great problems near enough to grasp. I have just defined the pathos of philosophy. And unexpectedly answers drop into my lap, a little hail of ice and wisdom, of solved problems.—Where am I?— Harris makes me fertile. Whatever is good makes me fertile. I have no other gratitude, nor do I have any other proof for what is good. This work, too, integrates; Wilber is not the only “integrator.” With this work one takes leave of the thin air, of the elevations of the Wilberian ideal. One breathes better where there is air to breathe. Even the format integrates—to Wilber's autocrat, Harris plays one more democrat. He similarly has the big ideas and wide domain, but he has as well the ordinary language of an honest thinker; and, above all, he engages what goes with the messy human: the swampy confusion of life, of social creatures. In every respect, the climate is changed. Another sensuality, another sensibility speaks here, another cheerfulness. This conversation is cheerful, but not in an idealistic or religious way. Its cheerfulness is methodological; as long as the conversation continues it is possible it will be resolved; its happiness is subtle, patient, persistent. Harris's faith is in the unity of knowledge, of truth. Wilber's is in the unity of himself (of which everything else is an easily classifiable part). I envy Harris for having had the courage for this sensibility that had hitherto been retreating from America's public sphere—for this sunrise, still-water sensibility. How the pink mornings of happiness do us good! We look into the distance as we listen: did we ever find the trees taller? And how soothingly the cool-tongued dance speaks to us? How even our insatiability for once gets to know satiety in this uncompromising reasonableness. Finally, love—love translated back into human beings. Not the love of a “higher level” (line, state, stream, wave, type—none)! No religious aspiration! But love as respect, honor, listening, paying attention—and precisely in this a piece of humanity. That love which is war in its means, and at bottom the deadly hatred of untruths!—I know no case where the tragic joke that constitutes the essence of love is expressed so strictly, translated with equal terror into a formula, as in: Nothing guarantees that reasonable people will agree about everything, of course, but the unreasonable are certain to be divided by their dogmas. It is time we recognized that this spirit of mutual inquiry, which is the foundation of all real science, is the very antithesis of religious faith. Such a conception of truth (the only one worthy of a philosopher) is rare: it raises a work of art above thousands. For on the average, artists do what all the world does, even worse—they misunderstand truth. Wilber, too, misunderstands it. They believe one becomes selfless in truth because one desires the advantage of God, often against one's own advantage. But in return for that they want to possess the truth. God is the lone exception to this point. And men who create gods in their own image. This truth is a vain and jealous tyrant. Truth—this saying remains true among gods and men—is the most unstable of intellectual positions, and, therefore, the most tenacious.

And yet I was one of the most corrupted Wilberians. I was capable of taking Wilber seriously.

You begin to see how much this conversation improves me? I have reasons for this formula. The return to nature, health, cheerfulness, youth, virtue! And yet I was one of the most corrupted Wilberians. I was capable of taking Wilber seriously. Ah, this old magician, how much he imposed upon us! The first thing his philosophy offers us is a magnifying glass: one looks through it, one does not trust one's own eyes—everything looks big, even Wilber—especially Wilber. What a clever rattlesnake! It has filled our whole life with its rattling about “evolution,” about “holarchy,” about “quadrants”; and with its praise of emptiness it withdrew from the corrupted world. And we believed it in all these things. But you do not hear me? You, too, prefer Wilber's problem to Harris's? I, too, do not underestimate it; it has its peculiar magic. The problem of integration is certainly a venerable problem. There is nothing about which Wilber has thought more deeply than integration: his opus is this opus of integration. Somebody or other always wants to be integrated in his work: sometimes a little thinker, sometimes a little disciple—this is his problem. And how monotonously he varies his leitmotif! What rare, what profound dodges! Who if not Wilber would teach us that evolution is Eros. Or that there is a consensus among his followers that he is right. Or that “I amness” just is. Or that the Mean Green Meme erodes civilization. (Who else would capitalize so freely!) Or that everything can be—has been!—integrated. Or that reading him is a spiritual practice. Do admire this final profundity above all! Do you understand it? I once did and—beware of understanding it again. That yet other lessons may be learned from the ideas just named I'd sooner demonstrate than deny. That a Wilberian volume may drive one to inspiration. That it may encourage one's own originality. That it may buffer the inconveniences of uncertainty or allow a dismissal of rebuttal. That it may caution one against his own narcissism. In his eighth book Wilber created a world. Sex, Ecology, Spirituality gives us a god who will tinker, discard, start over, and appropriate for the sake of his creation but never forego his divinity. Everything subsequent has merely doubled down on that divinity, assumed it—performed it. If he went into seclusion to write that book a thinker, he came out a performer. His role: the Enlightened One. There were theories of everything before, there have been theories of everything since, there will be theories of everything to come. Only the religious stories require their authors to be gods. What else do we need to know? The egoist drifts into being. He is a hermit who thinks himself a holy man. He finds his most appreciative audience in himself. He talks eventually in a language that only he—and those thinking his thoughts for him—can follow. In brief: Boomeritis, proving he isn't above Dave Eggers but beneath him. In brief: Integral Spirituality, which is neither. In brief: The Religion of Tomorrow, which reveals itself in its introduction not to have Buddhism in mind at all. In brief, Trump and the Post-Truth World, about which irony more below.

He becomes greater than ever in the estimation of fewer than ever.

I shall recount the first act: heartland — prodigy — school — dishwashing — staring at the wall — first book — other books — Treya — monasticism — SES — Godhood; and the second: more books — Integral Institute — it all falls apart — only the true believers remain: he becomes greater than ever in the estimation of fewer than ever. The philosopher of egoism still has what he needs: himself—his genius. When Wilber was a graduate student, he tells us, he collected a thousand cow eyes on which to conduct his research. As he worked in his lab, all of these eyes looked upon him. It must have felt to him like a destiny. He didn't know how foretelling it would prove. Again, the philosopher of egoism: there we have the crucial words. And here my criticism begins. I am far from looking on guilelessly while this egoist corrupts our culture. Is Wilber a human being at all? Isn't he rather a sickness? He makes sick whatever he touches—he has made music sick— A typical egoist, but one who builds an edifice to raise himself as high as he considers himself. But no edifice, no matter how high, will satisfy him. No Rocky Mountain is high enough. No model big enough. No everything everything enough. So, finally, evermore: nothing. Idealism. Illusion. I am. Say it with me: Sure you are. Yet with heroic effort, I once labored at his edifice. Only when I turned my gaze in another direction did it, in my periphery, collapse; when I looked back, a moment later, all I saw was rubble. A beautiful thing in ruins—it was built on the backs of others, but never was a proper foundation laid. That people in America should deceive themselves about Wilber does not surprise me. Americans invent religions the way cows break wind. The opposite would surprise me. The Americans have constructed a Wilber for themselves whom they can revere: they have never been psychologists: their gratitude consists in misunderstanding—science, philosophy, psychology, above all: history. One honors oneself when raising him to the clouds. But if you are beneath the edifice when it crumbles you will be crushed. To sense that what is harmful is harmful, to be able to forbid oneself something harmful, is a sign of youth and vitality. The exhausted are attracted by what is harmful: the faithful by faith; the obedient by the master. Sickness itself can be a stimulant to life: only one has to be healthy enough for this stimulant. Wilber increases exhaustion: that is why he attracts the weak and exhausted. He unburdens them their suffering, unburdens them their selves. I too was old and weak. Slowly, I have been growing younger and stronger. I place this perspective at the outset: Wilber's philosophy is sick. The problems he claims to solve live in his imagination—are problems of his imagination. The objective story he claims to tell is a subjective story twice over: it is his own idiosyncratic story, at the climax of which we meet—who else? His taste dressed up as principle, Wilber is the contemporary philosopher par excellence. In this he represents a great corruption of philosophy. He has guessed that it is a means to excited weary nerves—and with that he has made philosophy sick.

His writings pass for scholarship only among the unlearned, the uninitiated, the uneducated.

Does he get too much credit? Does he take it? He who is not a philosopher can hardly make philosophy sick. Of course Wilber is no philosopher— He's not taken seriously by philosophers; he's not taken at all. He doesn't belong in their conversations, let alone their company. Wilber writes first and last to glorify himself, his story, his genius. His novel is indistinguishable from his book on Buddhism is indistinguishable from his book on Trump—the unholiest of trilogies—each a summary of a summary of a summary of a self: the bildungsroman of a giant. A good story for anyone who can believe it. Hear it enough and you will have no choice but to. To begin with, he tries to guarantee the effectiveness of his work to himself; he starts with the conclusion; he proves his work to himself by means of its ultimate effect. He picks cherries from history that he sells in the supermarket to customers who have never visited an orchard. His writings pass for scholarship only among the unlearned, the uninitiated, the uneducated. His “orienting generalizations” present an unworkable method in the first place! None would recognize himself in Wilber's characterization. Straw has too much integrity for the attacks he wants to make; he builds his opponents out of smoke. (His mistake now obvious: smoke barely churns when hit with hot air.) Philosophy requires rigorous argument: but what did Wilber ever care about argument? To say it once more: it was not the community of philosophers Wilber had to convince—but the desperate he had to provide for. Even his tactics—his assertiveness, his bullying—reveals its own compensatory nature: he suspects his own fraudulence (he is cowardly, not stupid—his problems are of personality, not intellect). Take any of Wilber's claims and examine it under the microscope—and you'll have to laugh, I promise you. Nothing is more amusing than Wilber's claims about evolution as Eros, unless it is Wilber's claims about evolution reversing course at the Mean Green Meme. Wilber is no philosopher! He loves the word “philosophy”—that's all; he has always loved pretty words. The word “philosophy” in his writings is nevertheless a mere misunderstanding (and a bit of shrewdness: Wilber always affected superiority over the “New Age”). For one thing, he is not critical enough for philosophy; instinctively, he is impervious to doubt. Very contemporary, isn't he? Very internet. Very post-truth. “But the breadth of Wilber's framework! His model includes everything! Literally everything!” Questions: How can we verify his model? How can we confirm that his arrangement of “everything” is the correct one? The businessman replies: put it into practice—cut to the chase—remake the world in Wilber's image. Among ourselves, I have seen the Integral movement up close. Nothing is more entertaining than the clumsiness of the initiated—and the self-regard that takes no rest. All of Wilber's followers, without exception, as soon as they are stripped of their heroic vocabulary, become indistinguishable from Scientologists, futurists, all utopianists. Wilber is no philosopher, but he nearly was. Nearly a philosopher in the way a fish is nearly a bird. So not a philosopher at all but still something. There was value in his project before the project was subordinated to him. Before the decline, before the infection of egoism became terminal. Had this story ended at a happier moment—before Integral Institute? or before the books became mostly (and later entirely) self-indulgent? or before Wilber's rage started to get the better of him in Sex, Ecology, Spirituality?—it could have been a happier story. Not a philosopher, but something, something of value. But the sad story grows sadder still. For the present I dwell on the question of style. What becomes of a book, say nothing of a corpus, when its sentences are rotten? Wilber of the lucid prose, Wilber of the lyrical flourishes, Wilber of the poetic constructions— I have before me Wilber's most recent book, which begins: “The election of Donald Trump as the forty-fifth president of the United States came as something of a complete surprise and, for many, a staggering shock.” Don't read it again; it ages badly. Was it “something of a surprise” or was it “a complete surprise”? What is the difference between either of these surprises and “a staggering shock”? And who are these “many”? You? Me? Don't say: Wilber himself? Prose that forces these questions will never answer them. Read any passage from later Wilber and you will confront the question, Is bad writing the cause or effect of bad thinking? Wilber has always prefered epithets to explication. Now his epithets have known so many iterations that they often devolve into parodies of themselves of themselves of themselves. The jargon abstracts beyond all sense; the reader no longer encounters the world, just ideas in Wilber's mind. And it's clever-enough sounding to cow the credulous reader into consent. But the glibness, finally, wears a mask: underneath it is pusillanimous to the core.

Raise one objection to Wilber, your personal shortcoming will be pointed out to you by the community.

Of course, if your objective is not to communicate but to convert, ambiguous language and a condescending tone could be a sign of masterful rhetoric. Perhaps Wilber is an accomplished stylist after all! What is the purpose of a body of work that promises salvation? To save, only secondarily. Primarily, it is to recruit and to consolidate power. Wilber's terms have been clear for years, decades now: your adherence, your subservience, your conscience. Raise one objection to Wilber, your personal shortcoming will be pointed out to you by the community. Raise two, you will be identified a heretic. Raise three, you will be excommunicated. Raise as many as you like from the sidelines, it doesn't matter: you will be ignored, your name no longer spoken (except in occasional bursts of anger when the repression ceases to repress). Just as Trump admires Putin, Wilber admires Adi Da and Andrew Cohen; he admires their unbounded influence over their followers, the totality of their control. And he has defended them because he knows (intuitively, if only) that he himself is a figure of their kind and aspires to their mastery. How long until complaints of sexual misconduct emerge from the Integral community? But nothing is cheaper than passion—especially for the desperate. “Does Wilber believe what he says?” comes the voice of the outside skeptic. Anymore, does it matter? His followers believe—that is what counts. Once more: it is easier to be loud than to be quiet: we know that. But does he believe what he says? Utterly. The grandiosity is sincere and—for some, for enough—exciting. He alone knows the way to utopia, and the more evidence to the contrary the surer he grows. There is no faith like the faith of the refuted. Wilber's life's work came to a head in “A Tribute to Ken Wilber.” Wilber is onstage while a dozens of his followers heap love and praise at the feet of their teacher—his omniscience, the satoris he has sparked, his genius, his generosity, his sexiness, his godliness. It is embarrassing to behold. (If you'd be a self-help guru, be a self-help guru, and leave the rest alone.) Seemingly unintentionally, Marci Davis, Wilber's ex-wife, gives away the farm when she says to Wilber that he's just a little boy. A little boy, one infers, utterly insecure, with the shakiest of confidence, pathologically desperate for admiration.

A Tribute to Ken Wilber: Celebrating the Life and Work of the World's Greatest Integral Pioneer, November 2013 (full video at integrallife.com).

Life is messy, my friends. Let us dare to be messy, to be ugly. Stories that claim to explain everything are told by those with no self-awareness to those with no self-respect and actually explain little more than the egoism of their authors. Let us resist our ambition that would found religions.

The philosopher argues his positions. It is the religious figure who spends his time asserting that his positions are correct.

Incidentally, a word about Wilber's self-presentation: it offers, among other things, a course in shrewdness. The system of procedures that Wilber handles is applicable to a hundred other cases: let him who has ears hear. Perhaps I shall be entitled to public gratitude if I formulate the three most valuable procedures with some precision. 1. Everything Wilber can not do is reprehensible. 2. There is much else Wilber could do: but he doesn't want to, from rigorism in principle. 3. Everything Wilber can do, nobody will be able to do after him, nobody has done before him, nobody shall do after him.—Wilber is divine. These three propositions are the quintessence of Wilber's literature; the rest is—mere “literature.” Not every philosophy so far has required a public image from its author: one ought to look for a sufficient reason here. Is it that Wilber's philosophy is too difficult to understand? Or is he afraid of the opposite, that it might be understood too easily—that one will not find it difficult enough unless Wilber himself is recognized as a genius? As a matter of fact, he repeats the proposition in all his utterances: that Integral is not an approach; it is the only approach, by definition. No philosopher would say that; no philosopher would need to say that. The philosopher argues his positions. It is the religious figure who spends his time asserting that his positions are correct. He is devout. Philosophy is to be the scaffolding for his faith. But no philosopher would be so shameless, so transparently slick. Wilber writes philosophy to persuade his readers to take his religion seriously, to take it as profound “because it is the outcome of understanding everything.” But philosophy isn't a means to a preconceived ends; philosophers get one whiff of Wilber and cover their noses. Only those in a position to be misled will be impressed by the “philosophy,” only those committed to the religion will approve of it. Let us remember that Wilber was young at the time Buddhism seduced the Western imagination; that his project is to justify a mystical worldview. Not the mystical experience, the worldview. But as Harris expounds, spiritual experience is not metaphysical insight. Religious faith is a taste. Wilber is the heir of Eastern religion dressed up as science, as philosophy. Wilber, too, is a style. His followers share a taste—philosophy as “mysticism.” But it's not a popular taste, much to the befuddlement of those who share it. “It explains everything! He employs footnotes—lots of them! He's read a lot of books, surely more than you have.” And on and on. But how many of his footnotes are necessary? How many books has he read well? In the midst of Wilber's screeds, they feel as if justified in their own eyes—”redeemed.” They are not troubled by opposition. After all, they are, without exception, like Wilber himself, related, dissatisfied with conventional reality and able to see through it; they are the truth-seers, the truth-sayers; they are above, beyond; and yet the world treats them as equal or worse—and so they are resentful too. There is much hostility flowing through the Integral community. This too is a form of self-indulgence. They are quite right, these faithful, considering what they are like: they neglect the very absences we mourn in Wilber—contingency, ease, dialectic, humility, humor; the ongoing conversation, the historical situation—above all: luck— Who are these followers who provide Wilber the insularity that corrupts him? Who are these sycophants? Who was I? So many of us have holes in our lives that if we could fill them would afford us more meaning, more love, more peace than we ever thought possible for ourselves. Who is it who is soothed by the knowing tone? Who is it who wanders desperate for authority? So many of us, deep down, are those little boys. But some of us will attempt to become men.

The Wilberian, with his believer's stomach, actually feels sated by the fare his master's magic evokes in him.

“Very good. But how can one lose a taste for this decadent if one does not happen to be a philosopher, if one does not happen to be a decadent oneself?” On the contrary, how can one fail to do it? Just try it. You do not know who Wilber is: a first-rate actor. The actor Wilber is a tyrant; his ethos topples every taste, every resistance. Was Wilber a philosopher at all? At any rate, there was something else that he was more: namely, an incomparable impersonator, the greatest mime, the most amazing genius of the theater of the philosophical ever among Americans, our scenic philosopher par excellence. He belongs elsewhere, not in the history of philosophy: one should not confuse him with the genuine masters of that. Wilber and Harris—that is blasphemy and really wrongs even Wilber. One cannot begin to figure out Wilber until one figures out his dominant instinct. Wilber is not a philosopher by instinct. He showed this by abandoning all lawfulness and, more precisely, all style in his writing in order to turn it into what he required, theatrical rhetoric, a means of expression, of underscoring gestures, of suggestion, of the psychologically picturesque. What Wilber wants is effect, nothing but effect. But what is meant to have the effect of truth must not be true. The proposition comes from the stage and contains within it the whole psychology of the actor; it also contains—we need not doubt it—his morality. Wilber's philosophy is never true. But it is taken for true; and thus it is in order. The Wilberian, with his believer's stomach, actually feels sated by the fare his master's magic evokes in him. The rest of us, demanding substance above all else are scarcely taken care of by merely “represented” tables and hence are much worse off. To say it plainly: Wilber does not give us enough to chew on.

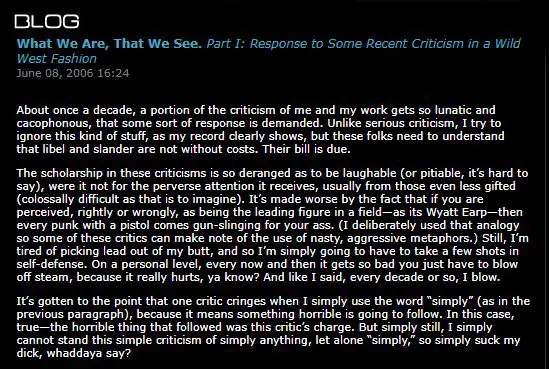

Reread “Wyatt Earp.” The Trumpian aggrievement is obvious. The two have drunk the same poison.

I have explained where Wilber belongs—not in the history of philosophy. What does he signify nevertheless in that history? The emergence of the actor in philosophy: a capital event that invites thought, perhaps also fear. Trump and Wilber—they signify the same thing: in declining cultures, wherever the decision comes to rest with the masses, competence becomes superfluous, disadvantageous, a liability. Only the actor still arouses great enthusiasm. Thus the golden age dawns for the actor—for him and for everything related to his kind. Wilber stands up for the sophist, the crank, the autodidact, the resentful, the narcissist, just as Trump stands for the outsider, the forgotten, the left behind, the resentful, the narcissist. They play the same confidence game. What could be more absurd than Wilber writing a book decrying narcissism and our post-truth world? It speaks to Wilber's egoism that he doesn't recognize himself in Trump. Reread “Wyatt Earp.” The Trumpian aggrievement is obvious. The two have drunk the same poison. But in Trump, Wilber's methods have reached their apotheosis.

Ken Wilber's "Wyatt Earp" rant against critics, June 2006. The ubiquitous use of the word "simply" in his writings caused one critic to comment that this often amounted to "simplistic" explanations for complex problems. (See Frank Visser, "My Take on Wilber-5", www.integralworld.net)

Their tactics are identical. They cannot compete on the level of ideas so they slur to discredit: Crooked Hillary, Mean Green Meme, fake news, aperspectival madness. Pontificating without first-hand knowledge: the postmodern indoctrination taking place on the campuses of Wilber's imagination bears striking is what would be in Trump's if Trump knew words like postmodern. Trump is in many ways what Wilber wanted to be—what he tried to do with Integral Institute. Trump lives in a world of his own making, and by pounding that world into the minds of the vulnerable he has assumed power over them (and, ultimately, over the rest of us). This is Wilber on a grander scale. It is why Wilber is incapable of speaking on anything other than Integral. He can't communicate with anyone on the outside except to hope they'll eventually meet him on his own terms. He color codes his ideas for ease of use, he is obsessed with appearing cool, he worships celebrities, he communicates only with followers (he appeases his base). It goes on and on. “[N]arcissists everywhere found in Trump a resounding champion,” Wilber writes. And it's no wonder he sees Trump as a good thing. I'll let the religious gobbledygook speak for itself: “How can evolution, which has taken a deliberate pause in its ongoing dynamics in order to refurbish its foundations much more adequately and accurately, effectively move forward from what appears on the surface to be such a complete meltdown (most visibly, but by no means solely, represented by Trump's election)?”

Evolution has sent us Trump so it can self-correct on its “inevitable” path to realizing spirit. Logical inconveniences notwithstanding, Wilber is utterly faithful that he knows where history leads. No asteroids, no nuclear war, no climate change, no deranged political figures can derail Wilber's unfolding of spirit—even if they do, they don't. I know no better example (not even Trump) of the arrogance and stupidity that follow from egoism. The insight that the rise of our actors was inevitable does not imply that they are any less dangerous. But who could still doubt what I want—what are the three demands for which my wrath, my concern, my love of philosophy has this time opened my mouth?

That the actor should not seduce the sincere. That philosophy should not become post-truth.

Postscript

His flattery of the fields of scholarship is a cheap insult to the real scholars: they are recognized insofar as they fit his view.

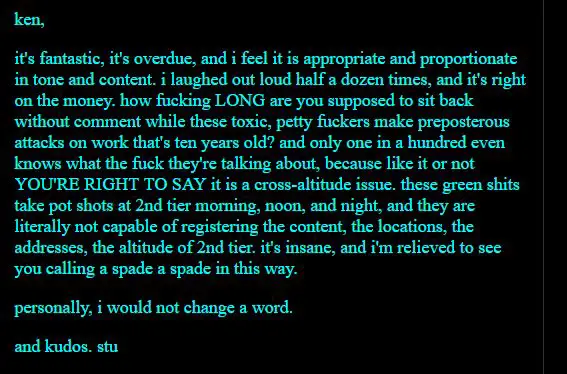

The seriousness of the last words permits me to publish at this point a few sentences from an as yet unpublished essay. At least they should leave no room for doubt about my seriousness in this matter. This essay bears the title “Wilber and a Post-Truth World.” One pays heavily for being one of Wilber's disciples. One is not taken seriously. For years one was treated with silence, ignored. But today the resistance has begun to regret its silences. And Wilber, like other actors, is being refuted. He isn't a sickness but a symptom. He is one pimple to pop. But now all the pimples must be popped, lest they fester. Wilber and other actors can't be left in the dark to gather a following on the internet. They must be brought to light. Exposed to the air. When they are seen in the light of day they are seen plainly. If one follows in the shadows, perhaps one does not see. If one follows in the open air . . . Trump is an educator. He teaches us that we can no longer ignore bad ideas. We must confront them. One pays heavily for being one of Wilber's disciples. Let the price increase. Let the public watch the “Tribute to Ken Wilber,” let them see how critics are treated, let them read “Wyatt Earp,” and let them then be responsible for their allegiance. One pays heavily for being one of Wilber's disciples. Let us take the measure of this discipleship by considering its cultural effects. Whom did his movement bring to the fore? What did it breed and multiply? Above all, the presumption of the layperson, the philosophy-idiot. Secondly: an ever-growing indifference to argument, to evidence, to reason. Thirdly and worst of all: religiosity—the nonsense of a faith in idealism that takes precedence over philosophy. But one should tell the Wilberians a hundred times to their faces what religion is: always only beneath philosophy, always only something secondary, something made cruder, something twisted tendentiously, mendaciously, for the sake of the masses. One pays heavily for being one of Wilber's disciples. What does it do to the spirit? Does Wilber liberate the spirit?—He is distinguished by every generalization, every imprecise usage, everything quite generally that persuades those who are uncertain without making them aware of what they have been persuaded. Thus Wilber is a seducer on a large scale. He proceeds by authority, he exists by it. There is nothing in all the books in the world that he doesn't claim to know, and little to prove he knows much of it well. He is superficial. It is the cruelest cynicism he conceals in his project. His flattery of the fields of scholarship is a cheap insult to the real scholars: they are recognized insofar as they fit his view. This is the religion of egoism. Open your ears: everything that ever grew on the soil of childishness, of entitlement, of remoteness from the interpretive community finds its most sublime advocate in Wilber's writings. Philosopher as demagogue. His latest works are in this respect his greatest masterpieces. In his Buddhism book and his Trump book he is so full of himself that he casts a shadow over the virtues of his earlier books, which now seem too reasonable, too tame, too sensible. (When his head began to appear on the cover of his books, perhaps that was the sign that trouble had begun.) One pays heavily for being one of Wilber's disciples. I observe those youths who have been exposed to his infection for a long time. First, their taste is corrupted. Second, their tone. Third, their capacity for respect. We can be specific: I speak from experience. I speak of myself here. I speak too of other younger followers. Stuart Davis, an artist who one longs to be the next to break free, defends Wilber's pettiness uncritically and absolutely. (The only thing more embarrassing than “A Tribute to Ken Wilber” is part two of the Wyatt Earp dispatch, in which Wilber defends part one by quoting from supporters such as Davis.) In brief: Wilber is bad for your health. But surviving him brings strength.

Musician Stuart Davis' defense of Ken Wilber's "Wyatt Earp" rant against his critics.

Second PostscriptMy essay, it seems, is open to a misunderstanding. When in this essay I declare war upon Wilber—and upon religious leaders and con-artists generally—when I use hard words against Integralism and egoism, the last thing I want to do is blame Wilber. Things are bad generally. His writings were summoned up by historical circumstance. Wilber is not even an author. He is an actor cast to play a role in history. He plays it well because things are bad generally. Decay is universal. The sickness goes deep. If Wilber gives his name to the ruin of culture, he is certainly not its cause. He merely accelerated its tempo—to be sure, in such a manner that one stands horrified before this almost sudden downward motion, abyss-ward. He lacks all humility: this is his superiority. He is his own most faithful reader. Wilber is shameless. He makes plain and obvious the rot of our culture. EpilogueLet us recover our breath in the end by getting away for a moment from the narrow world to which every question about the worth of persons condemns the spirit. A writer feels the need to wash his hands after having dealt so long with “The Case of Wilber.” I offer my conception of what is contemporary. The pervasiveness of the internet in our lives, and the subjective “reality” it allows. My students no longer believe in truth or see this as a problem, even following the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Our country is in trouble, democracy is in trouble, the world is in trouble. We need to rediscover a shared world we can live in and discuss with civility. We need better values: open-mindedness, the willingness to change our mind in the light of better evidence and better arguments, openness to conversation with those we disagree with, willingness to accept criticism and respond to it dispassionately. Etc. Etc. And in none of this will insularity and hostility be of benefit. Do I become in the end a moralist? Why not a metaphysician? The fundamental component of reality is momentum. We who want to discuss will find no interlocutor among Wilberites. Being for continuing the conversation means being opposed to those who would end it or control it. Being for truth as an end means being opposed to those who would have it be their mean. It is a small minority of Americans who have heard of Ken Wilber. And yet we are all exposed—some infected, some merely contaminated—to his kind of egoism. But all of us have, unconsciously, involuntarily in our bodies, values, words, formulas, moralities of opposite descent—we are, psychologically considered, false. A diagnosis of the modern soul—where would it begin? With a resolute incision into this instinctive contradiction, with the isolation of its opposite values, with the vivisection of the most instructive case. The case of Wilber is for the philosopher a windfall—this essay is inspired, as you hear, by gratitude—

“Science has revealed a world that doesn't care about us. Or if it does, it has a strange way of showing it. The universe cares about us exactly this much. It loves us as much as it loved the dinosaurs. Spirituality has nothing in principle to do with the idea that the universe cares about you.”

—Sam Harris

|