|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992). David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992).

THE AGNOSTICS

Thinkers in an Indeterminate Cosmos

Introduction |

Isaiah Berlin |

Charles Darwin |

John Dewey |

Enrico Fermi |

David Hume |

Edmund Husserl |

Thomas Henry Huxley |

Thomas Kuhn |

Lynn Margulis |

John Maynard Keynes |

G.E. Moore |

Karl Popper |

Michael Schmidt-Salomon |

Herbert Spencer |

Leo Szilard

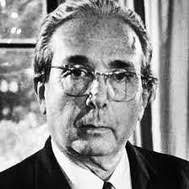

LEO SZILARDYizhi ZhangLeo Szilard, a Hungarian-American physicist, inventor, and microbiologist. His major contribution involves the development of the nuclear chain theory in 1933 and the nuclear fission reactor Chicago Pile-1 in 1934. In 1939, he wrote the letter for Einstein's signature that directly resulted in the establishment of the Manhattan project for building atomic bombs. He has also contributed to a variety of subjects such as linear accelerator, cyclotron, electron microscope, information theory, microbiology, and world peace.  Leo Szilard Leo Szilard was born in Budapest Hungary on February 11, 1898, in a Jewish family. There are four members in his family: his father Louis Spitz, a civil engineer; his mother Thekla Vidor; and his two siblings, brother Béla and sister Rózsi (Rose). He was first born as Leo Spitz, in 1900 October 4th. The family changed their surname to Szilard which means “solid” in Hungarian. Leo Szilard was exc exceptionally smart since he was little; he attended Reáliskola high school in his hometown and showed talent in physics and math. He won the Eötvös Prize (national mathematics prize) in 1916. In the same year, he enrolled at the Palatine Joseph Technical University in Budapest as an engineering student. During the time he was studying, he also joined the Austro-Hungarian Army's 4th Mountain Artillery Regiment during World War I. Before he got sent to the front line, he caught the so-called Spanish influenza (later research indicates it may have come from America) and was sent to home for treatment. Luckily, he avoided the battle that was most likely going to kill him, since almost all members of his regiment died in the combat. After being discharged honorably in November 1918, he returned to school the next year. On December 25, 1919, he enrolled at the Technische Hochschule (Institute of Technology) in Berlin-Charlottenburg and later transferred again to Friedrich Wilhelm University (University of Berlin) as a physics major student. The experience in Friedrich Wilhelm University influenced Szilard greatly. Hewould often attend lectures given by Albert Einstein, Max Planck, Walter Nernst, James Franck, and Max von Laue. During the time in school, he made a close friendship with Albert Einstein, which later led to the success of the Manhattan Project. Szilard earned his Ph.D. in 1922 and later worked as an assistant to Max Von Laue. In 1927, he became a private lecturer in physics and was responsible for numerous inventions. In the following years, he submitted several applications for patents onhis invention of a linear accelerator, cyclotron, and electron microscope. He also developed the Einstein refrigerator with Albert Einstein; however, it required too much energy to operate and made too much noise so it was mainly used only for the nuclear reactor. In 1933, Szilard had a major turning point in his life. Hitler came to power and his anti-Semitism forced many Jews to seek refuge in England where he eventually settled for a time. In the same year, he conceived the idea of the nuclear chain reaction. While in England, Szilard worked in St Bartholomew's hospital in 1934 and developed the Szilard-Chalmers effect used in medical isotopes. He also continued his research on physics in England, where he collaborated with many individual physicists and worked as a research physicist at the Clarendon Laboratory in 1935. In those years, he traveled several times to America and eventually moved to New York City in 1938 and settled at Columbia University. In January, Niels Bohr announced the discovery of nuclear fission by Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann. This gave Szilard the idea of using uranium to sustain a chain reaction. He made an experiment at Columbia University and proved that such a chain reaction is possible. On August 2, 1939, Szilard drafted a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. In the letter, he explained the chain reaction and claimed the possibility of nuclear weapons. He also asked Einstein for his signature on the letter. Under the pressure of Nazi Germany and World War II, the U.S. government accepted the proposal and ultimately created the Manhattan project. Due to the attack made by the Japanese on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. government provided more support to the project for the development of the atomic bomb. In January 1942, Szilard joined the Metallurgical Laboratory in Chicago. From that time until the end of the war, Szilard continued his research on nuclear at the University of Chicago. In 1943, he became a citizen of the United States. At the end of World War II Szilard quit the field of physics and became a biologist in 1946. He worked with his ex-colleague Aaron Novick from the Metallurgical Laboratory and made several remarkable contributions to the study of biology which includes the invention of a chemostat, which is a method of calculating the growth rate of bacteria, and the feedback inhibition. Szilard found out he had bladder cancer in 1960; he personally designed his own regimen and on the second round he insisted on increasing the dose of radiation that wasn't recommended by the doctor. The higher dose cured him and became the standard of usage in radiation until today. In his last few years, he spent it in La Jolla, California as a fellow of Salk Institute for Biological Studies. On May 30, 1964, Leo Szilard died in his sleep. Although Leo Szilard helped in the development of the atomic bomb, he was always a strong supporter of world peace and human rights. Szilard never wished that the U.S. would use atomic bombs directly, but only as a viable threat that would force German and Japan to surrender. He drafted the Szilard Petition and contributed to the amendments to the Atomic Energy Act of 1946. In the petition, Szilard argued that the atomic attack on Japan “could not be justified, at least not until the terms which will be imposed after the war on Japan were made public in detail and Japan were given an opportunity to surrender.” In 1949, He wrote a short story named “My Trial as a War Criminal.” In the story, he expressed the guilt he felt due to his participating in the war. He also focused the public's attention on the danger of nuclear weapons and radiation. Ten years later, he published a collection of satirical sketches entitled, The Voice of the Dolphins and Other Stories that talks about how the misuse of knowledge can be a disaster. Szilard was raised in a religious Jew family, but later declared himself an agnostic on matters pertaining to religion. Clearly his studies in physics and biology deeply influenced him and helped him formulate a more humanistic and scientific outlook. Szilard's views on God are in line with Einstein's when his mentor and friend wrote, [The word God is] “nothing more than the expression and product of human weakness.” He also considered the Hebrew Bible “honorable, but still purely primitive legends.” Leo Szilard realized that science was a double-edged sword because it was a tool used by flawed human beings. As he famously quipped, “I have been asked whether I would agree that the tragedy of the scientist is that he is able to bring about great advances in our knowledge, which mankind may then proceed to use for purposes of destruction. My answer is that this is not the tragedy of the scientist; it is the tragedy of mankind.” Szilard could also be quite funny in how he used “God” as a placeholder, even though like Einstein he was a believer in Nature and not some personal deity, as when he once retorted, “ I am thinking of keeping a diary, not with the intend to publish it, merely to record the facts for the information of God, in case God does not know my version of the facts.” He was also a remarkably clear thinker who wasn't so worried about getting credit as he was about making sure that he got the facts correct. As he once explained, “A scientist's aim in a discussion with his colleagues is not to persuade, but to clarify.”

Further Reading1. Leo Szilard: His Version of the Facts 2. Genius in the Shadow: A Biography of Leo Szilard, the Man Behind the Bomb 3. Toward A Livable World: Leo Szilard And the Crusade for Nuclear Arms Control

FROM THE INTRODUCTION | DAVID LANE

Often in the philosophy classes I have taught in undergraduate and graduate school, I would bring up this point of “unknowingness.” Pointing to a crumpled piece of writing paper, I would ask the class, “What is this?” Almost in unison, the students would respond, "A piece of paper." Taking this as my cue to lead into a deeper philosophical investigation of materialism, I probed further, "Yes, but what is that?” Catching my drift, one student invariably answered, “Oh, it is actually a transformed sheet of wood.” Not wanting them to stop there, I asked, “And wood is made of what?” “It's comprised of molecules," the more scientifically oriented students would shout. Connecting to the now forgotten inner space ride at Disneyland, which takes one through an imaginary voyage inside a snowflake molecule, I queried, “But what is a molecule made of.” By this time, we had gotten down to the subatomic level, and our words began to betray our modicum of knowledge (electrons, protons, quarks, lucky charms, superstring). The final question I asked was quite simple, but given the line of investigation it led to some severe complications: What is matter? Well, it should be obvious to the reader as it was to my class and to myself that there's only one truly appropriate response, “I don't know.” Now, this is exactly the response not only of most mystics, but most quantum physicists as well. As Sir Arthur Eddington, the distinguished astronomer put it, “Something unknown is doing we don't know what!” To be sure, mystics have said that the world (or matter) is nothing but consciousness. But, what is consciousness? Not even a sage as enlightened as Ramana Maharshi of South India could answer that question. To such queries, Ramana would often sit in silence. Ultimately, matter leads to consciousness and consciousness to God or Nature (with a capital N) and both to Mystery. However, no matter how you define it, slice it, categorize it, blend it, intuit it, the fact remains that Reality is a Mystery, and nobody apparently (not me, not you, not Einstein) knows what that Reality is. We are sitting right in the middle of the Mystical Dimension.

Comment Form is loading comments...

|