|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

David Christopher Lane David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992). The Evolution of Meditation

Why Understanding the Mind-Brain

and its Permutations is Helpful

David Lane

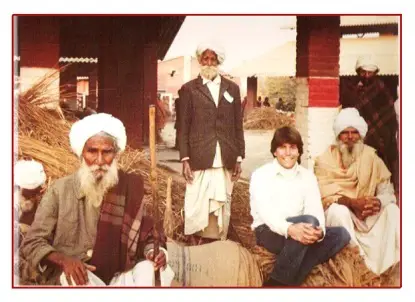

The author with an interesting crew in India, circa 1983

What kind of meditation are you doing? Could this be flavoring your interpretations of what you believe must be the case?

I must say that I was quite impressed that my little essay, "The Netflix of Consciousness", generated a pointed and engaging rejoinder from Andy Smith ["There Is No Hack"]. He is very clear on why he disagrees with several of my key points and goes right to the jugular when he parts company with my major thesis which is that “Understanding why the mind operates as it does versus believing outdated and dualistic models (usually religiously oriented and far too often dogmatic in their retelling) can be of tremendous help in stilling the mind.”

Andy's counter-argument is: “It is really no help at all.”

He then proceeds to back this up with the following analogies:

“That's like saying that if a man understands that evolution selected for males that could copulate with as many females as possible (as opposed to, for example, the Biblical notion that God made men superior to women), thus maximizing the spread of their genes, this will help him with his problem with philandering or promiscuity. Or that knowing that fat rich foods were vital to our ancestors as a quick source of energy (rather than, God gave us the ability to enjoy taste) will help people stick to a diet. These are important facts to know, and one can argue that any educated person should be cognizant of them, but they won't help with the process of overcoming our built-in drives.”

His argument is that cognitively knowing why humans function the way they do from a scientific perspective (versus a mythic or religious one) “won't help with the process of overcoming our built-in drives.”

I beg to differ for several obvious reasons. First, it does indeed help males (and I would add females into the mix as well) to know why they have a certain drive to spread their genes by understanding their biological machinery. Only by such knowledge can they come to grips with the factual mechanics of their own anatomy (and not some metaphysical mumbo jumbo). How so? Whenever one has a deep insight into how a process actually works and why it arises, such knowledge provides a pathway in which to better understand how it might be modified. If I see sexual desires as a natural ebb and flow that is bound to arise versus as a curse or a sin that must be overcome due to the fall of Adam and Eve (ah, as one of our Catholic priests told us Freshman year at Notre Dame High school), then one doesn't have to undergo a cosmic fight with Satan and his minions because of an unexpected erection. No, understanding the naturalness of something alleviates and can obviate all sorts of mistaken notions that only add to the confused adolescents' mind.

To modify any behavior or any structure it is elemental that one has the correct model of how and why the person or object operates as it does. Otherwise, one is shooting bullets in the dark and nothing gets accurately transformed. This is why I mentioned why it is important for an auto mechanic to know that the engine under the hood is a four or six cylinder. Claiming that such knowledge “won't help” is, of course, ridiculous.

Let me see if I can give a slightly different analogy along these lines before I tackle Andy Smith's point about dietary habits.

In the tech world there are those wonderful young minds who love to “mod” the latest gadget. When I was teaching at California State University, Long Beach, there was this teenager who wasn't a very good student, but who was an absolute whiz when it came to tinkering and improving old Virtual Reality headsets. He had a comprehensive and keen knowledge about the pros and cons of old VR gear. With his extensive knowledge and his mechanical abilities and having 50 or so old headsets, working out of his Dad's garage, he somehow figured out how to dramatically improve VR goggles. In a short, but intense period of time, he came up with the Oculus Rift and partnering with several others he sold his jerry-rigged invention to Mark Zuckerberg and Facebook for nearly three billion dollars.

My point? Understanding mechanics is a prerequisite to being able to modify such. So, my argument is quite simple: yes, knowing the ins and outs of our anatomy and its various functions can indeed help us if we wish to alter, change, or even slightly modify how it operates. This doesn't mean it will be easy, but there is no doubt that without such requisite knowledge we are lost at sea.

Let's apply this now to Andy's point about diet. He argues that “knowing that fat rich foods were vital to our ancestors as a quick source of energy (rather than, God gave us the ability to enjoy taste) . . . . won't help with the process of overcoming our built-in drives.”

Ah, to the contrary. It will help very much knowing such facts. I know this from my own life since I have been a vegetarian (now vegan) for the past forty-seven years. I remember when I was eleven or twelve and my father and I discussing how fat gets stored in the body and why it was vital to know the caloric breakdown of various fruits, vegetables, breads, and so on. Because I had an extensive understanding of what was “in” the food it helped me in making wise decisions about what I would ingest and what I wouldn't. The oft used cliché' is right on the mark here: “knowledge IS power.”

Let me give a funny example that I saw on television decades ago concerning a young man who suffered from insomnia. He just couldn't get a good night's sleep, try as he might. He worked hard during the day and also at night, so he couldn't understand why he was having such difficulty dozing off. So, he went to his doctor and they tried this or that remedy. It didn't work until finally the doctor asked him about his food and drinking habits. Well, long story short, it turns out that this young man was a huge fan of drinking Pepsi cola and he drank five or six of them at night as he was working in the garage. He apparently had no idea that such drinks had a decent dose of caffeine in them (37.6 mg per 12 fluid ounce) and was startled that this drinking habit of his could be the culprit. He gave up the colas and presto he was cured from his “incurable” insomnia.

Did knowing about the caffeine content of the drink help him alter his behavior? Most certainly.

Therefore, I quite disagree with you when you argue that knowing the fat content of food “won't help with the process of overcoming our built-in drives.” Yes, it will, particularly if we start paying attention to what we eat since we now have pertinent information about how such can make us fat. Moreover, that very desire for fats and sugars can be manipulated by a variety of substitutes which mimic their high caloric counterparts. My son, Shaun, was a great fan of Sprite since he liked the carbonation and the flavor, but knowing what it did to his body (time for a mantra repeat, “knowledge is power”) but still having the same desire he realized that there was a “hack” that had been developed by the food industry (see Waterloo Sparkling Waters). Put natural mango or strawberry flavoring into carbonated water and discard the sugar. Tastes quite good and has absolutely no calories. What did this information do? It did exactly what Andy says it can't. Following the science, it developed a healthy way to appease an evolutionary drive.

Take drugs as another illustrative example. Does knowing how DMT or LSD works help us when we are under its spell? Certainly. Not knowing what they do can do much more harm than good. Imagine the difference between one who knows how long a DMT session will last and what it might portend versus one who is given a dose unknowingly?

My wife Andrea brought up the notion of visual illusions (given her background as a research assistant to V.S. Ramachandran some thirty-five years ago at the University of California, San Diego) as another illustrative way to understand how knowledge can transform one's reaction to a given phenomenon. I think everyone has already experienced this when they see a mirage when driving in the Mojave Desert. If think that slope ahead is full of water then my reaction can cause an accident or worse. If, however, I know that it is a trick of the noonday sun, then I drive much more relaxed and avoid the unnecessary plunge off the side of the road.

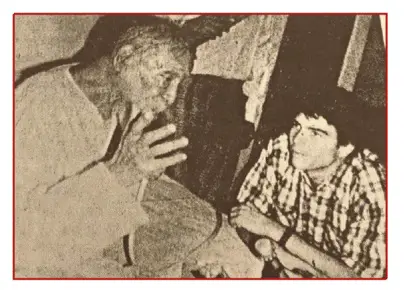

Baba Faqir Chand, the great sage of Hoshiarpur, who had intensely meditated for some seventy years told me personally back in the summer of 1978 that the greatest help he ever received in meditation was the realization that all the inner visions and lights that he saw were merely projections of his own mind and had no permanent ontology in themselves. As Faqir explained,

“O' Faqir these satsangis have taught you the method of hanging at the gallows. Only this experience of the manifestation of my form at different places, of which I am never aware, has changed my life. . . My experiences prove that Yogi, Meditator, Guru, Disciple and even the aspirant of salvation are in bondage. . . These people who create my form with their mental forces to fulfill their worldly desires are not interested to know the Truth. They do not hang themselves on the gallows, because they depend on the support of my Form. Whereas to a man on the gallows there is no support. This is the highest stage.”

So, let's put this into sharper relief, particularly how it relates to meditation. Faqir readily admits that “knowing” that his form manifested to his disciples without his conscious awareness allowed him to be “liberated” from the very visions he was seeing in his own meditation. Instead of buying into outdated mythic explanations for why such visions arise, Faqir took a more rational and logical approach and was thereby helped tremendously in his interior explorations.

Baba Faqir Chand (then 92) being interviewed by the author (then 22)

In fact, I remember Faqir telling me on more than one occasion that it was vital that a meditator have the right understanding of how the mind operates in order to be liberated from its machinations. The Tibetan Book of the Dead, of course, goes even further and suggests that such knowledge is a requisite for not being caught once again into the cycle of samsara:

“As the Bardo Thodol [sic] text makes very clear by repeated assertions, none of all these deities or spiritual beings has any real individual existence any more than have human beings. "It is quite sufficient for thee (i.e., the deceased percipient) to know that these apparitions are (the reflections of) thine own thought-forms." They are merely the consciousness-content visualized, by karmic agency, as apparitional appearances in the Intermediate state -- airy nothings woven into dreams.”

Knowing precisely why the mind operates the way it does (versus some antiquated and dualistic religious notions) is especially beneficial, particularly when we realize that all “mods” and all “hacks” are predicated first and foremost on having the right specs.

This is why Siddhartha Gautama's Four Noble Truths and his Eight-Fold Path can rightly be seen as “hacks.”

Buddha says suffering exists. Something we can all experience. Is it important to know why it occurs? Of course, so what does Buddha tell us? Desire is the cause of suffering.

Does this knowledge potentially help us in alleviating some forms of suffering?

Yes, just as knowing the caffeine content in a Coke can help us understand why drinking such keeps us up at night.

This is why Buddha's eight-fold path is actually a form of knowledge and being conversant with such information is in itself helpful.

“1. RIGHT VIEW

A true understanding of how reality and suffering are intertwined.

2. RIGHT RESOLVE

The aspiration to act with correct intention, doing no harm.

3. RIGHT SPEECH

Abstaining from lying, and divisive or abusive speech.

4. RIGHT ACTION

Acting in ways that do not cause harm, such as not taking life, not stealing, and not engaging in sexual misconduct.

5. RIGHT LIVELIHOOD

Making an ethically sound living, being honest in business dealings.

6. RIGHT EFFORT

Endeavoring to give rise to skillful thoughts, words, and deeds and renouncing unskillful ones.

7. RIGHT MINDFULNESS

Being mindful of one's body, feelings, mind, and mental qualities.

8. RIGHT CONCENTRATION

Practicing skillful meditation informed by all of the preceding seven aspects.

These eight steps are considered to be of three types: right view and right resolve are related to our development of wisdom; right speech, right action, and right livelihood to ethical conduct; and right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration to meditation.”

It can be argued that the very reason Buddha (or whomever we wish to attribute these ideas to) came up with these guidelines was to get the neophyte the “right” kind of information so that their inward voyages would be helped. In other words, Buddha had developed a “Life hack (or life hacking) which is any trick, shortcut, skill, or novelty method that increases productivity and efficiency, in all walks of life.”

Okay, let's turn our attention to Andy's other point and one with which I have heard almost my entire life. Andy writes, “The short answer is that meditation is brutally difficult—and when confronted with something exceedingly difficult, human beings naturally search for an easier way. It's sometimes possible to find an easy way to get rich, an easy way to become famous, even a (relatively) easy way to make a lasting contribution in science, art, literature, sports, entertainment, and so on. But there is no easy way to meditate. There are no short-cuts; there are no hacks.”

Here I find myself once again disagreeing with Andy, since it can be argued that all yoga, all meditational techniques, all ethical systems, dietary restrictions, ad infinitum, are in themselves hacks in precisely the way I am using the term.

That is why such schools of thought were developed. That is why Buddhism, particularly Tibetan schools, have developed all sorts of methods by which to calm the mind down.

Let me spell this out. Pranayama is a hack; asanas is a hack; mudras is a hack; dhyan is a hack; listening to the inner sound is a hack; mantras are a hack….. all designed to make it easier for one to probe one's own consciousness.

Yes, no doubt, we have to do the meditation ourselves but even that very word “meditation” is a hack in the very real sense of that term.

Jagat Singh, a respected shabd yoga guru, once famously opined that “ninety percent of spirituality is clear thinking.” So, it is with meditation. Knowing how the mind operates is a huge help and that very knowledge (as underlined by the Tibetan Book of the Dead and from a plethora of yogis and gurus and mystics I have met during my eleven trips to India) all echo that same sentiment.

This is why Jnana yoga, the way of knowledge, can cut through a truckload of unnecessary garbage since it wants the aspirant to see things as they are, not as we delude ourselves. Perhaps a series of pregnant quotes from Ramana Maharshi would highlight this better:

“Realisation is not acquisition of anything new nor is it a new faculty. It is only removal of all camouflage”

“Let what comes come. Let what goes go. Find out what remains.”

I, myself, meditate anywhere from two to five hours a day. I love the practice. Now whenever we say something like “meditation is brutally difficult” it reveals an assumption that I suggest is in itself a roadblock, a way to make something more troublesome than it need be.

I remember my friend in India telling me that constantly repeating a mantra and sitting for hours trying to still the mind was like “licking a dry stone endlessly”. Others would sometimes nod in agreement. I didn't get it.

I thought those kinds of sentiments were exactly one of the reasons their meditation was so painful to them.

Ramana Maharshi touches upon this when he says, ““There is no greater mystery than this--that being the Reality ourselves, we seek to gain Reality. We think there is something binding our Reality and it must be destroyed before the Reality (Truth) is gained. It is ridiculous. A day will dawn when you will laugh at your effort. That which is on the day of laughter is also now.”

Andy then axiomatically claims something that deserves closer inspection because I suggest it is wrong on the surface:

“But there is no easy way to meditate. There are no short-cuts; there are no hacks.”

Huh? The whole process is a hack, as I tried to point out by a variety of examples. And let's be clear, some forms of knowledge and better than others. This is why I argue that having a deep understanding of evolution and neuroscience is a great help since it clears up mythic cobwebs that can too easily entrap one with all sorts of mental gymnastics, just as getting rid of Roman Catholic nonsense about sex can help a young teenager better understand his or her body and why it desires this or that.

As the eight-fold path point out, “right views” are essential and to argue otherwise is to miss out on a key solution to how meditation can progress without so much torture.

Andy suggests that “Another obstacle, which David notes, is that meditation does not seem to be an activity in which linear progress is possible.”

If I gave that impression then the fault is mine, since I don't believe that at all. In fact, one can make tremendous progress, though I am not quite sure what Andy means by linear as I would use different terminology.

What I was driving at is that goal-oriented meditation tends not get the desired results one wants and therefore can (as Sam Harris and a plethora of other meditation teachers have pointed out) produce the opposite effect.

Speaking for myself, I clearly see that it is much easier for me to meditate now than ever before and I didn't elaborate about my own depth experiences since as I suggested it is, as Ram Das famously wrote in Be Here Now, just more painted cakes which are in themselves inedible. Yes, there are certainly some very telltale signs that happens in deeper and deeper meditation. But as I once critiqued Ken Wilber and others in the essays "Projective Arc and Theological Tethering", there is an inherent danger in trying to match one's perspective with what their chosen guru or path says one should see or hear or experience. Joseph Dillard summarized this conundrum well when he wrote, “This is essentially a correspondence-based epistemology which asks, 'Does my meditation experience match the descriptions and injunctions of my teachers?.'”

There is a danger here which can lead to all sorts of strange one-upmanship games where disciples of different masters and traditions volley back and forth about how their particular realization is “higher” or “greater” or more “comprehensive” than the other. Sorry for my vernacular but I call this the “dick game” where one pontificates about the largeness of their penis versus their opponent's angry inch.

It is nauseating and I have seen it far too much in my research over the years on cults, gurus, and spiritual movements—whether in India, England, France, Switzerland, or North America.

So, yes, I don't disagree that there are varying stages in meditation. But I think Andy is missing the point when he suggests that “Many people, have the impression, imagine that they can continue to live more or less as they always have, and just sit in meditation for some period of time every day.”

Yes, many people can indeed sit that way and I don't see that as a problem if they are enjoying themselves.

If that floats their boat, so be it.

Now, granted, if someone wants to venture deeper or take a different route then that necessitates other aspects of one's life, but let's be clear here.

Meditation has many variables and many varying aspects, a point I tried to drive home to Andy eleven years ago in the essay, "Consciousness, Meditation, and a Higher State: A Definitional Debate?" when I wrote

“Now again I find Mr. Smith making sweeping generalizations that are both misleading and inaccurate when closely examined. Why? Meditation isn't a singular act upon which all practitioners agree. There are many varying schools of thought which use meditation for a whole set of reasons, some for raising the kundalini, some for listening to an internal sound, some for developing stillness of mind, some for aligning the mind with God's will. The list goes on. So for Mr. Smith to say something as dogmatic as “The point is that the higher state of consciousness is the goal of meditation is not about using or focusing our attention in a different way” is to merely proffer his own opinion about what he thinks meditation is all about.

In other words, it would be much more accurate to say “I, Mr. Smith, believe that meditation should be about such and such.” It might be interesting to see which form of meditation Mr. Smith actually has in mind so that our discussion could proceed in a more specific fashion.

But even if we place this corrective parameter on Mr. Smith's sweeping generalizations about what meditation is for, he adds a tautology which doesn't progress the discussion beyond a priori platitudes and dogmatisms. Writes Mr. Smith, “Higher consciousness is about raising the level of awareness.

Period.” Period? Are we having a scientific discussion of consciousness (which by its very nature must be inductive/open) or are we merely sprouting forth spiritual axioms? If the former, then adding periods to any discussion leads nowhere. If the latter, then we are not in Kansas anymore and we are having is a not so sophisticated theological (or should I say “meditationalogical”?) debate?

I say this because Mr. Smith has already assumed what is and what isn't an “illusion,” as if seasoned meditators couldn't be just plain mistaken about their own interpretations of what occurs during meditating.”

Andy then goes on to quote Brad Reynolds (again dogmatically and with a preset and singular definition of what he thinks meditation should be):

“As Brad notes, meditation must go on all the time, and this means that your entire life has to change. A major reason meditation is so difficult, for anyone beginning, is because our lives unfold in ways that keep us in sleep. This goes back to what David said about evolution. We have evolved in a way that guarantees that our mind will be in constant motion, but mind is intimately connected to body. The kinds of thoughts we experience are related to the activity that we are doing at that time. So any attempt to challenge our thinking patterns inevitably means we must also confront what we are doing from day to day. Not to do so would be sort of like trying to divorce a partner while still not only living together and having sex together, but maintaining the outward relationship in exactly the same way as it was. How we act and what we experience are mutually reinforcing.”

I would agree with this if (and my if should be bolded here) we are talking about a specific or certain form of meditation that one is advocating. Others may simply want to do another route in their sitting and not change anything else in their life. That too is fine.

Thus, what Andy is assuming is that his version of meditation involves this and that. Okay, that is fine, but let's spell out that metaphysical agenda first since it is far too obvious that Andy's agenda for meditation is his. We already know Brad Reynolds affiliation to all things Adi Da, and reading Andy's writings between the lines one gets the impression that he holds to a certain school of thought on meditation. It may not be my view and therein lies the rub.

But let's bite the bait and see where it leads us.

Andy continues but, in the process, slightly upends his previous citation of Brad Reynolds, “This goes far beyond the 'unhealthy habit patterns' that Brad emphasizes, though. In fact, a certain kind of diet is not essential for successful meditation, though some diets are obviously healthier for us than others (here Brad may be falling into the same kind of fallacy that David is, assuming that what science tells us about our minds and bodies can help us meditate).”

Again, Andy restates his thesis quite clearly when he writes (taking Brad to task), “Here Brad may be falling into the same kind of fallacy that David is, assuming that what science tells us about our minds and bodies can help us meditate.”

Let's unpack this a bit since I think it is patently false. Knowing how your body works certainly can help one meditate. That is why yoga was invented since our body directly influences our mind. To think otherwise is not only naïve but completely wrong. Lest we forget, meditation is done in our body and cannot be divorced from it, and therefore understanding how it operates is fundamental to how and why our mind/brain responds the way it does. This is so transparently obvious that I am surprised that Andy could make such a sweeping mistake.

But Andy continues in this vein, “The same is true with regard to exercise and sexuality. Society, through science, tends to claim that some approaches to exercise or to sexuality may be healthier than others, and I certainly wouldn't advise anyone to ignore the data underlying these claims. But my point remains that what science or society says about healthy lifestyles is pretty much irrelevant to meditation. Other than keeping you in the game for as long as possible, healthy living will not have much effect on meditation. It's something that you need to do—like having enough income to pay for food, shelter and clothing--but it will not increase your awareness”

Analyze Andy's statement closely and see how completely wrong and off it truly is, “what science or society says about healthy lifestyles is pretty much irrelevant to meditation.”

To the contrary, what science tells us about healthy lifestyles is remarkably relevant and helpful to meditation, so much so that much of Indian spirituality is based on such knowledge. In fact, I will go even further and say that knowing how the body functions and how it influences the mind-brain is absolutely essential. Saying it is irrelevant is akin to saying that hydrogen and oxygen are unnecessary to make water.

Seriously, Andy, do you really think that what science informs us about how our body functions and what we eat and drink and what it does to our body is inconsequential? Really think about that for a second. We clearly do not see eye to eye here.

At this junction I would like to point out that I think saying something is a “must” is unwarranted, unless we are focusing on a certain kind of meditation and what it offers.

Andy writes, “If you listen to Brad—and I think David accepts this, too, though he hasn't emphasized it in his article—you must continue to meditate even while you engage in your daily routine.”

While I too like to meditate even when doing other activities (especially when surfing), I don't think it has to be a dictum where “you must continue to meditate while you engage in your daily routine.”

It is optional and depends on what one wants out of the practice.

Interestingly, Andy then (perhaps unconsciously?) contradicts my very thesis that knowing something can actually help in meditation by positing his own principle that he claims “will definitely guide you for the rest of your life.”

Look closely at how Andy upturns the thrust of his entire essay in the following extended passage,

“If you are rigorous and honest in your practice, you will eventually notice that your awareness decreases when you get up from sitting and start doing something. Indeed, this is why meditation is so often discussed as though it were the same thing as sitting, because greater awareness is possible during this time. But why? At first, you might believe it's because you're distracted, by tasks you have to do, by people you must interact with, and so on. And certainly these are, or can be, factors. But suppose you make a concerted effort to get rid of external distractions—no noise, no other people around, no task to perform other than, say, a relatively mindless one of getting up and moving somewhere (think, for example, of the process of Zen walking, attempting to meditate exactly as when sitting, but while walking)—you will still lose awareness. Why?

Understanding the answer to this question is one of the most profound lessons of meditation. If you grasp this one principle, it will definitely guide you for the rest of your life. The reason you lose awareness is because your body moves. To do this requires energy and--herein lies the lesson—this is exactly the same energy that raises one's awareness. There is competition, which is to say conflict, between your body's needs for energy to do anything (even to maintain a default state in stillness or sleep), and that which fuels increasing awareness.

Let's step back a moment. What exactly happens in the brain during meditation? As I pointed out earlier, it's a process of stopping thought, though it can be described in many other ways. Every thought that passes through your mind requires energy, and when that thought is stopped, that energy becomes available for increasing awareness. From a purely scientific point of view, meditation can be defined as a process of diverting energy that would normally be used in mental activity into some kind of storage. An obvious metaphor that comes to mind is damming a river. To the extent that one stops the flow of the water, that water can be stored—in a lake, for example—where it is available as potential energy. In the brain, that storage, that potential energy, manifests to us as enhanced awareness—the more energy stored, the higher the awareness.

But this stored energy can also be tapped into by the body for its ongoing needs. Hence, there is a never-ending contest, or tug-of-war, between storing energy as higher awareness, and using it for physiological processes. When you sit, you reduce your body's needs for energy to a minimum, which means your awareness can rise, relatively unhindered, at a maximum rate. And conversely, when you stop sitting—that is, when you get up and start to move--you lose awareness, because your body needs energy to move, and it will take some of that energy from your increased awareness.”

Andy alleges that “the reason you lose awareness is because your body moves.” And if you understand this, he proclaims, “it will definitely guide you for the rest of your life.”

Huh? I thought nothing science tells us can help us in meditation, Andy, but you just wrote (somewhat axiomatically, by the way) that “understanding” this will change our lives. Don't you see that having a deep insight (scientific or otherwise) into how energy operates can help one in meditation? Of course, it can and I find it deeply ironic that you cannot confess the obviousness of it.

But Andy persists down this same trail making claims that I think not only warrant further inspection but which I find not necessarily true since he provides no supporting evidence outside of his own conjecture,

“I want to repeat this, because it's extremely important, and I believe very few people realize it. It doesn't matter how hard you try to meditate when you are walking, for example, you will not increase your level of awareness as fast as when you are sitting. And if you have been sitting for a while before walking, you will lose some of your awareness when you then start walking. This process has nothing to do with being distracted, with not trying hard enough, with losing your interest, or any other explanation or excuse you might come up with. It's simply an observable fact that this always happens. And again, I will be blunt here: anyone who doesn't experience this simply has not achieved a high enough level of awareness to realize it. You have to have some enhanced awareness to appreciate that you can lose it, and because measuring your level of awareness is a very difficult art (I will discuss this point later), you generally must undergo this process many, many times before what is going on fully dawns on you.”

While I like you drawing on your own observations, I find it troubling when you can (without wincing) say, “I will be blunt here: anyone who doesn't experience this simply has not achieved a high enough level of awareness to realize it.”

Sound a bit too dogmatic, Andy, especially if you are trying to make an evidential argument. Perhaps it would be a bit more prudent and a bit less arrogant for you not to confuse your own anecdotal experiences with the sum lot of all other humans. Can you be wrong? Or is this some inviolate law that you discovered that cannot be upended? Are we not in Kansas anymore or are we in Gumby Land thinking?

Andy then elaborates on his meditating energy theory suggesting that our attention is like batteries where “the chemical reactions in the battery causes a buildup of electrons at the anode. This results in an electrical difference between the anode and the cathode.”

We better keep those batteries continually charged or they will leak energy and all that we gained will be lost. Andy elaborates,

“Now we are in a position to understand why meditation must go on all the time—not just a few hours a day, let alone as something one does only when one has time or finds convenient. The energy that we accumulate through meditation is very unstable. If we stop meditating, not only will no more energy accumulate, but what little we have acquired will gradually be commandered by the body for other purposes. Even if we were to sit quietly indefinitely, if we were to stop meditating at some point, that stored energy would eventually be used by the body for self-maintenance. And as soon as we get up and start behaving in any manner physically—or indeed, just thinking in a highly focused manner—the loss is accelerated. Meditation is a Sisyphean task, like rolling a stone up a hill. If we pause for even a moment, the stone starts to roll back down. This in fact is not just a metaphor, as it accurately depicts the concepts of energy maxima and minima”

Actually, Andy, it is a metaphor since you haven't given us sufficient evidence to wholly support your claim, except to tell us that it is factual.

Perhaps you should spill some biographical beans here and tell us what kind of meditation you do since that may give us a better understanding of your argument, since otherwise it is starting to sound too much like yin yang theology lecture I once heard from an obscure guru in the summer of 1983 while studying Hindi in Mussoorie, a hill station in the Himalayan mountains.

What kind of meditation are you doing? Could this be flavoring your interpretations of what you believe must be the case?

Andy you make some claims that don't at all dovetail with my own experiences in meditation. For instance, you write, “But very large changes in awareness can result from changes in our behavior. For example, if you sit one morning, then engage in an unusual amount of physical activity that day, your level of awareness the next morning is likely to be lower than it was the previous morning.”

Maybe for you, but that has not been my experience at all. Actually, quite the opposite. I have long noticed that intense physical “activity” is extremely helpful for my meditation. Prolonged surf sessions (sometimes hours on end) actually helps my meditation.

The author (then 16)

The author (then 16)

meditating after surfing

I realize that you may have a different experience, but I think we are on slippery grounds when don't envision counter examples that may upturn our sweeping generalizations.

Near the end of your essay (which I thoroughly enjoyed, even if we disagree on many salient points) you write, “I began this discussion by arguing that David Lane's claim that knowing the evolutionary origin of our wandering mind can help us meditate is overstated.”

We disagree. I think knowing the evolutionary origins of our wandering mind is quite helpful and has been for me in my meditational sojourns. I can summarize my viewpoint in three words and it is a mantra I have repeated twice before in this essay: “knowledge is power.” And the more accurate that knowledge, the more successful we can be in the long run.

On a more autobiographical note, I learned much in my many research trips throughout India first starting back in the summer of 1978. My job at the age of 22 was to meet and interview various gurus throughout Uttar Pradesh and the Punjab and develop a comprehensive genealogical tree of differing guru lineages for my Professor at U.C. Berkeley that was eventually published in 1991 by Princeton University Press. I have been back many more times on related projects, most recently in 2018 where there is a deep interest in Agra to scientifically study the effects of meditation and so on. I mention this because I do think the subject of meditation is a worthy one and I find it truly refreshing to have an intense discussion on a topic that is so close to my heart. Prior to our current virus crisis I was supposed to go back to India since we have a contract with Oxford University Press where I need to track down (once again!) the many guru and yogi offshoots….

I deeply appreciate you responding to my thoughts and I have tried to return the favor.

It is a great subject and I thank you for taking the time (and your energy…. Wink, wink) for engaging in such an illuminating topic.

I would enjoy learning more about your personal quest and perhaps you can reveal some autobiographical details if you feel comfortable. I will do the same in return.

In conclusion, you write, “Let's consider this further, using one of the simplest, yet commonest metaphors for meditation: climbing a mountain.”

I, naturally, have a different metaphor and perhaps this spells out better our differences. I don't see meditation as a mountain, though I understand its hierarchical implications. I see meditation as a form of surfing. What is it that surfers do? They ride waves for the bliss of it. Nothing more. I have found meditation to be extremely blissful and such a unique and wonderful privilege. It doesn't matter to me if I am on the top of the mountain, in the middle of the mountain, or not even on a mountain.

Just being able to explore our own consciousness is truly a gift.

I look forward to your future essay on this and related subjects.

“When we dance, the journey itself is the point, as when we play music the playing itself is the point. And exactly the same thing is true in meditation. Meditation is the discovery that the point of life is always arrived at in the immediate moment.”—ALAN WATTS

“What is called mind is a wondrous power existing in Self. It projects all thoughts. If we set aside all thoughts and see, there will be no such thing as mind remaining separate; therefore, thought itself is the form of the mind. Other than thoughts, there is no such thing as the mind.”—RAMANA MAHARSHI

“Be happy, don't worry.”—the ultimate mantra

Privacy policy of Ezoic

|

David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992).

David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992).