|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Dr. Joseph Dillard is a psychotherapist with over forty year's clinical experience treating individual, couple, and family issues. Dr. Dillard also has extensive experience with pain management and meditation training. The creator of Integral Deep Listening (IDL), Dr. Dillard is the author of over ten books on IDL, dreaming, nightmares, and meditation. He lives in Berlin, Germany. See: integraldeeplistening.com and his YouTube channel. He can be contacted at: [email protected] Dr. Joseph Dillard is a psychotherapist with over forty year's clinical experience treating individual, couple, and family issues. Dr. Dillard also has extensive experience with pain management and meditation training. The creator of Integral Deep Listening (IDL), Dr. Dillard is the author of over ten books on IDL, dreaming, nightmares, and meditation. He lives in Berlin, Germany. See: integraldeeplistening.com and his YouTube channel. He can be contacted at: [email protected]

SEE MORE ESSAYS WRITTEN BY JOSEPH DILLARD  Core Concepts Of ConfucianismChina's Contribution to an Integral World View, Part ThreeJoseph Dillard

Confucianism is highly unusual because it embodies a secular humanism that was incorporated into the governing structures of entire civilization.

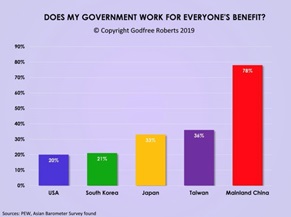

Confucianism is highly unusual because it embodies a secular humanism that was incorporated into the governing structures of entire civilization, in fact, the oldest continuous civilization on the planet. Master K'ung's ethical philosophy springs from a desire to create and defend order as well as a desire to minimize chaos. This is because Chinese society, as noted above, was regularly and catastrophically upended by disastrous floods along its great rivers, by earthquakes, and by invasion, as China has no border mountain ranges to provide natural defense. In addition, governance itself was chronically unstable, with one lawless tyrant regularly being replaced by another in the various Chinese provinces. Order in China was based on two things: the structure of the family and the dictates of the Emperor. For there to be a healthy and secure society, individual stability had to be created and maintained. A top-down, beneficent tyranny, the type of government preferred by Plato and Aristotle, is compatible with both Confucian humanism and Chinese consciousness.[18] This was Master K'ung's fundamental project: to create a stable individual and personal foundation upon which a secure social order could be built. Therefore, Confucianism is very much a political philosophy, as is obvious from its elevation to canons of governance for over two millennia. Western attempts to imagine that the Chinese are suppressed by their government is wishful thinking in the extreme. In fact, surveys of Chinese show that their trust in their government far surpasses that of citizens of Western governments:  The above graph creates so much cognitive dissonance for the average Westerner that the immediate response is to attempt to rationalize or discount its reality and implications. These commonly include, “The Chinese are subservient and cowed out of fear into submission.” But the average Chinese scores 4-5 points higher in IQ than do Americans. Are more intelligent people more or less likely to be intimidated into submission? Until coronavirus, millions of Chinese went abroad each year as tourists. How many sought political asylum? If the Chinese were dominated by a totalitarian “authoritarian” regime, where are all the political refugees? Could it be that the Chinese are actually quite satisfied with their government? If so, doesn't that imply that what we have been taught about China and its government is radically mistaken? Core concepts from Confucianism are embedded in Chinese five year plans, that is, in the goals and directives from the very top tier of Chinese governance. The legal system of China exists

to serve a national goal that ninety percent of the population shares: the creation, in two stages—xiaokang and dàtóng—of a radically advanced society. In 2011, the Prime Minister defined xiaokang as 'a society in which no one is poor and everyone receives an education, has paid employment, more than enough food and clothing, access to medical services, old-age support, a home and a comfortable life' and, when China reaches that goal on June 1, 2021, there will be more drug addicts, suicides and executions, more homeless, poor, hungry and imprisoned people in America than in China. Guided by Xi Jinping Thought (which, like Deng's Thought which preceded it, is a plan and its ethical justification), the National Family will then attempt to create a dàtóng society, an advanced version of Marx's notion of Communism, 'from each according his ability, to each according to his need'. Once it is clear that virtually every Chinese is on board with this program, this account of the steps towards it makes sense.[19]

The concepts of two stages—xiaokang and dàtóng—of a radically advanced society, is derived from Confucius' Book of Rites, a classic text which had to be memorized by candidates for Chinese governmental positions for centuries. Therefore, Confucian ethics remain core to communist Chinese governance today, in harmony with a principle laid down by the Roman, Sextus Empiricus, in 200 AD:

The ethical is always more robust than the legal. Over time, it is the legal that should converge to the ethical, never the reverse. Laws come and go but ethics remain.

Master K'ung's genius was in creating a microcosmic form of self-governance by which to correctly order and regulate the macrocosm of family and society, in a format that continues to pass the tests of humanistic governance. His code of right relationships and moral excellence describes first the “superior man,” or junzi, then the family, and then the nation. Family relationships were the core of social, cultural, and ethical life for China, and the moral views of the Confucian tradition were essentially an amplification of familial virtues. By linking the structure of the family and the dictates of the Emperor to a common set of underlying personal virtues, Master K'ung hoped to generate order in both families and the nation. His core formulation of this code stands the test of time:

If there be righteousness

Master K'ung encouraged strong familial loyalty, ancestor worship, respect of elders by their children, and the family as a basis for an ideal government. He emphasized study (UR) to learn what virtue is (LL), personal (UR & LR) and governmental (LR) morality, correctness of social relationships (LR), and justice (LR & LL), and sincerity (LL), so that individuals could properly serve both family and nation (LR). Confucianism lacks an afterlife and its texts are relatively unconcerned about the nature of the soul. Ancestor worship is to be understood as honoring tradition and expressing familial piety, not as placating spirits as in shamanism. Confucianism expresses complex and ambivalent views concerning deities, probably as a result of the synchronistic mixing of folk, Taoist, and Buddhist traditions, and it is relatively unconcerned with some spiritual matters often considered essential to religious thought, such as the nature of the soul.

The Microcosm and Macrocosm Mirror Each OtherThe Way of Heaven discloses itself in the order of nature. Natural patterns are summarized by human, microcosmic values that describe virtues, such as harmony, peace, beauty, truth, wisdom, acceptance, love, and compassion and are projected onto nature and onto the Creator of nature, or “Heaven,” and made sacred as the Will, Order, Way, or Dharma of Heaven. These values, qualities, or virtues are then conceptualized as rules and laws to regulate society and the affairs of men. That Order is to guide not only individual action, but thinking and values as well. The microcosmic values of men are to mirror the macrocosmic values of the Way of Heaven. This is the logic of divinely rationalized rulership in all times and places. Divine grace and power, referred to as “Heaven” in traditional Chinese thought, flow to the people through the wisdom and beneficence of its chosen servant. The role of the monarch or ruler is to uphold the Way of Heaven by defending its laws by subjecting the actions of men to them, to hold all to account to that measure. This may not be so different from the Western monarchial justification of “the divine right of kings,” in that the right of rulership is proclaimed to be divinely given, in a formulation that is convenient for both rulers and maintaining social stability. In any case, under this formulation, the microcosmic fate of individual humans is determined by the macrocosmic Way, and the ruler is seen as the protector and link to this natural harmony, security, and order. It was Master K'ung's genius to turn this formula around, to stand it on its head by making a microcosm of interior values the genesis of a harmonious social macrocosm. In the West, an emphasis on the interior quadrants is typically associated with varieties of idealism, and therefore there is a tendency for the Western mind to project some variety of idealism onto Confucianism. But concepts of consciousness, spirituality, and the soul are foreign to Confucian secular humanism observed in the above quote. While Master K'ung believed in the mirroring of the macrocosm in the microcosm of human values, he also believed in the opposite: that the way to bring Heaven to Earth was to sprout Heaven out of Earth, to grow Heaven out of the hearts and minds of students, by nourishing Heaven's Way in the hearts and minds of individuals. The macrocosm was to reflect a virtuous microcosm. For Master K'ung, the order of the State mirrors the order of the character of its citizens. Therefore, it is imperative that the junzi, or Superior Man, be cultivated so that society can be governed by justice. Similarly, the order of the family mirrors the character of the Superior Man. The character of the junzi is determined by the virtues that he follows and upholds. The macrocosm mirrors the microcosm as the interior world of values is outpictured as the character of the Superior Man and his character is outpictured first in a harmonious family and then in a well-run state. Righteousness, or goodness in the heart, meaning an allegiance to virtue, generates beauty in the character, or in the actions of men. Excellence of character creates harmony in the home. When the homes of a nation are full of happiness, peace, and prosperity, then there will be social order. The government will be a reflection of harmonious families and beautiful character. It all begins with goodness in the heart of each individual. What is revolutionary about this formulation is that no longer does microcosm merely manifest macrocosm; now the social macrocosm is made to mirror the psychological interiors of humans. Man no longer has to be the victim of natural disasters, invasions, or despotic leaders, all of which manifest the Way of Heaven in unacceptable, irrational ways. Now it becomes possible for man, by the choices he makes in his heart, to create social order. This was not only a profoundly new idea in Chinese culture; it was a necessary and beneficial conception that answered a very genuine societal need. That is one important reason why the influence of Master K'ung has remained so strong throughout the vast majority of Chinese history and why it is foundational to China's Five Year Plans today. Government accountability is seen to grow out of and be responsible to, personal virtue. Morality is central to social relationships and governance. Both responsibility and control are placed within the choices of the individual regarding the values he adopts and the ways that he expresses them. This becomes something of an interpersonal yoga, in that it is a discipline of finding, restoring, and maintaining the appropriate balance within oneself and in relationships. Communism, or neoliberal economics, or whatever other form of government China may adopt, are merely vehicles for the manifestation of this underlying Chinese world view. Westerners miss that because Communism has been the adversary of choice of the West since the end of WWII. Far from trying to build a systematic theory of life and society or establish a formalism of rites, Master K'ung wanted his disciples to think deeply for themselves and relentlessly study the outside world. Consequently, Confucianism is more accurately considered an ethical philosophy and a series of social behavioral transactions dedicated to the development of character, not religious dogma. The virtues held by the Superior Man in the culture of his interior collective quadrant are expressed by the interior individual quadrant in the intentions that are core to the world view and cultural humanism Master K'ung teaches. Those teachings find manifestation in the actions of the junzi as he acts in just, respectful, righteous, and honest ways. This is then expressed by harmonious familial relationships and governance when such men are placed in charge of the nation, based on a system of strict meritocracy that goes back to Emperor Wudi. A causal chain is created that is vaguely reminiscent of the Buddhist Niddana, or twelve-spoked wheel of interdependent co-origination. Noble, harmonious intentions in the interior individual quadrant generate values, interpretations, perspectives, and worldviews in the collective interior quadrant, which feedback as feelings, thoughts, and consciousness in the individual interior quadrant. These in turn direct behavior in the individual exterior quadrant while determining interactional patterns in family, work, and governance in the collective external quadrant. Because values co-create this causal progression with intention to create our exterior socio-cultural reality, Master K'ung applied pressure to bring about profound changes in humanity by focusing on the interpretations, perspectives, and worldviews in the internal collective quadrant. What Master K'ung did not discriminate was the source of those values. He thought justice, goodness, honesty, and respect were the “given” or self-evident Way of Heaven. Such virtues did not require validation, but only to be taught and lived. In contrast, Integral Deep Listening takes a phenomenological approach. It does not assume that any values are valid, true or a priori. It assumes that there are no values that are given, only life. All values, other than the basic drive for survival, are provided by man to explain life, justify his choices and create harmonious personal and work relationships. For example, the six core qualities addressed in every interview are not viewed by IDL as “innate to nature,” but are inferences based on pranayama, observation of the round of breathing. Therefore, humans need to consult junzi, the “Superior Man” called by IDL our “life compass.” Not only is this Superior Man plural, in that each man has his own life compass, but you can know your life compass directly, through non-conceptual phenomenological experience, and indirectly, through conceptual experiences, such as Integral Deep Listening interviewing of dream characters and the personifications of life issues. Such conceptual experiences elaborate the critical values of the interior collective quadrant, not as Master K'ung did, by the assumed Way of Heaven, but by the values exemplified and explained by the many interviewed emerging potentials that score in a more balanced way than we do in core qualities of wakefulness. This earns them the status of “Superior Men” or junzi. When sufficient “junzi” are interviewed, a shared or average perspective or value orientation emerges. This points to the perspective of your life compass, which is a process rather than a static thing, being, or substance. While the life compass is always evolving, it can nevertheless be approximated by accessing its perspectives and recommendations through IDL interviewing. Such conceptual experiential access to the “Superior Man” frames and contextualizes non-conceptual experience, such as mystical access to experiences of unity in the upper left onto which we project various values, meanings, and interpretations of our lower left quadrant. Such filtering and interpretive projection is inevitable; what IDL interviewing does is supplement our own projections with the interpretations of multiple emerging potentials. The result is an experiential multi-perspectivalism, exhibiting an increasing likelihood that our perception of our life compass is realistic and useful. The result is a much more stable and authoritative foundation for values. Instead of being built upon the preferences of wise men like Ken Wilber, who declare they know the “Way of Heaven,” in this case a cognitive multi-perspectival map of self-development, solid, lasting values are discovered, validated, and amplified by each individual in their own personal rendition of Master K'ung's causal chain. Students of Integral Deep Listening do interviews to reveal, explain, and validate core values; these are conceptualized, first in interviews and then by each student for themselves. These concepts are then grounded in the applied recommendations from the interview. Concrete individual behaviors are undertaken in the yoga of an ongoing integral life practice, subject to the evolving priorities of one's life compass, the feedback of respected others, and one's own common sense, in a process called “triangulation.”[20] With that base of personal action, knowledge, and inner knowingness, the governance of self, family work, and state proceeds on a much more solid, stable, and lasting foundation.

Jen, the Core Confucian Virtue

Master K'ung regards devotion to parents and older siblings as the most basic form of promoting the interests of others before one's own. Those who behave morally in all relationships extending outward from the family probably approximated Master K'ung's conception of jen. Virtue flows from harmony with other people and a growing identification of the interests of self and other. Confucianism assumes humans are fundamentally good, teachable, improvable, and perfectible through self-cultivation, self-creation and collective interaction. Jen, (pronounced “ren”), or benevolence, also translated as “humanity” or “humaneness,” “compassion” or “loving others,” is the core Confucian virtue that is the source of all others. Acting according to jen is the first principle of Confucianism and means to put respect for the goodness and benevolence within others and yourself first. We have a responsibility to extend respect to others. Jen is human goodness and benevolence that is the foundation of humanity in that it makes humans distinctly human and life worth living. It is a sense of the dignity of human life, the foundation of all human relationships, and internally, a sense of self-respect. er through empathy with and respect for the perspectives and needs of others. While people are inherently good, jen must be cultivated and developed, which means that men can be and should be taught how to attain and express more human goodness and benevolence. Through the cultivation of jen a truly superior human being or junzi emerges. Junzi are not perfect in the sense that they never make mistakes, but in the sense that their moral character is true, their intentions are pure, and their actions are disciplined and aligned with that moral character. All people have the capacity to exemplify jen, mainly because all people are intrinsically good and therefore capable of operating in a way that is empathetic, humane and caring for others. When people are not educated or developed properly, jen is absent and people become undisciplined, uncaring, and hateful, opening life to chaos at every level. The world is considered ethical in its fundamental organization and the responsibility of humans is to cultivate virtue that is a manifestation of that moral order. As above, so below; the individual, to live in harmony with nature and society needs to cultivate that moral order within himself. This world view largely explains the strong traditional insistence in China on government service based on meritocracy. People are basically good, and anyone can learn to be junzi, but they have to be taught. And those with the greatest demonstrated junzi competencies earn the power and responsibility of governance. IDL extends that respect to interviewed imaginary perspectives: floor mats, cigarette butts, galaxies, and dust bunnies, not as some paroxysm of political correctness, but as a form of humility fitting to a student-teacher relationship, something Confucius understood and taught. This is based on the assumption that doing so strengthens the six core qualities, in particular acceptance, and that this acceptance is correlated with less emotional reactivity, better decision-making, greater enjoyment of life, and improved relationships. It is also extended to all characters and objects without distinction that are encountered in dreams, lucid dreams, trance, mystical, and near death experiences.

Reciprocity as a Core Component of Jen

Those with Jen do not treat others in ways they do not want others to treat them, a concept laid down by Confucius himself before 480 BC, contemporaneous to Gautama and just prior to Socrates, when he taught, “What you do not wish for yourself, do not do to others,” and “Since you yourself desire standing then help others achieve it, since you yourself desire success then help others attain it.” Another rendition of Master K'ung's concept of reciprocity is, “never impose on others what you would not choose for yourself.” Far from being an abstract or a stale legalism, this concept remains ahead of its time. The sophisticated technological culture of the twenty-first century is yet to catch up to this pronouncement which Master K'ung made some five hundred years before Jesus said much the same thing. What government of the world lives by it? What board of directors, what organizations, govern themselves today by this principle? What government, outside that of China, builds its governance plans around principles derived from an ethic of reciprocity? Although this statement, “never impose on others what you would not choose for yourself,” is normative, it conflicts with broad “same size for all” deontological, normative principles, in that it does not declare that you should treat others as they want to be treated or as some universal code would require, but as you would want to be treated. Since different people want to be treated in different ways, it honors the normative code of the individual by placing it above that of society. For example, one person may advocate for sex within marriage while another for polyamory, or multiple sexual relationships. Who is right? Generally ethical laws regarding sex are regulated by society for its own ends; the application of Master Kung's principle would produce different results for different individuals and different relationships, independent of the values of others or society. This formulation frees you to interact with others in any way that you wish, as long as they provide consent and as long as it is within the context of prevailing allowable social norms. Master K'ung's principle of reciprocity is about avoiding abuse instead of prescribing those things one should do. Of course, in practice, social norms limit individual preferences today, just as they did in Master K'ung's day, although those norms have changed radically over the centuries. Master K'ung's version of the golden rule is an obvious consequence of jen. Benevolence and humanity manifest reciprocity, which is foundational for Chinese personal, familial, and governmental behavior, as viewed from the Confucian tradition. Arguably, reciprocity as a foundation of ethical behavior historically plays a more central and important role in Chinese society than in any other. While one might point to this being the case for other cultures, since reciprocity is found in almost all world religions, in no other place has it taken humanistic, non-sectarian root on a civilizational scale. There are major cultural ramifications of basing morality on religious precepts and beliefs that do not necessarily follow, if instead morality is an expression of human nature itself, apart from dogma. Social order is more likely to arise from a need for balance, harmony, and education than from obedience, sin, guilt, or a drive toward purification. If we look at this difference in terms of Jonathan Heidt's varieties of determinants of moral reasoning, ethical behavior based on Confucianism is more likely to be associated with values of respect, care, and loyalty and less with fairness, purity, and liberty.[21] Jen involves the manner in which reciprocity is expressed, not only fulfilling one's responsibilities toward others and benevolence, but also goodness, authoritativeness, and selflessness. Cultivating or practicing such concern for others involves becoming “simple in manner and slow of speech,” being sure to avoid “artful” conversation or an ingratiating manner that would create a false impression and lead to self-infatuation. The contrast of this emphasis on humility with the self-centered individualism and superficial confidence typically found in Western advertising, politics, finance, and business management could not be more stark. However, ritualized or formalized humility is likely to be superficial and “artful.” Authentic humility is much more likely to be shown in service to others, regardless of their status, than in behaviors that are calculated to appear humble. It is instructive to observe the relative absence of the concept of humility in contemporary Western society. When it does appear, it is immediately suspected of being manipulative and a pretense. When cultural emphasis is placed on self-development rather than service to one's collective, the result is likely to be an emphasis on confidence, agency, and assertion, with humility regarded as a sign of weakness and vulnerability. Master K'ung regarded devotion to parents and older siblings as the most basic form of promoting the interests of others before one's own, as a humble subordination of one's own needs and status to those older and presumably wiser. Could any principle be simpler or more obvious? Is there any time in our life when we outgrow its relevance? Assuming that our familial role models are not abusive sociopaths, can the failure to learn and practice this principle in any society be anything but detrimental? Humility is an under-appreciated virtue that goes well with the elimination of personalization and the development of cosmic humor. It also follows the ancient and still quite prevalent Chinese model of proficiency: first demonstrate your core moral competencies in your familial relationships, then at school and in your work. If you do so, you are promoted and given greater responsibility over more people, money, and social structures. This approach can be clearly contrasted with work qualifications in the West, largely based on proficiency demonstrated by a resume, recommendations, and work performance. Morality is assumed, but rarely challenged or tested. Similarly, the morality of spiritual teachers in the West is assumed but rarely challenged or tested. Moral failings are typically ignored, discounted, and easily forgiven among business, political, and spiritual leadership until doing so is no longer possible. The Western default position assumes either morality, without evidence, or amorality, that is, that whatever is being done or implemented is viewed as necessary, and that necessity outweighs moral concerns. This “necessity” often boils down to valuing capital accumulation, power, and status above humanism, including reciprocity and human rights. Widespread support for Obama in the West, as demonstrated by his receiving the Nobel Peace Price before acquiring a record or performance in the office of President, provides a stark example.

Correlates of Jen to Integral Deep Listening

The correlate of Jen in IDL dream yoga is to treat all beings with dignity and respect. This is extended beyond the intent of Master K'ung to the domain of sentient beings recognized by Buddhism, and yet beyond that to clearly and obviously imaginary constructs such as dream toasters, cartoon characters, figures from mythology, fiction, science fiction, and romance novels. IDL extends jen to imaginary and illusory entities, to all characters and objects without distinction that are encountered in dreams, lucid dreams, trance, mystical, and near death experiences, based on a thorough-going phenomenalism that suspends ontological assumptions about the reality and usefulness of entities and objects encountered in either objective or subjective domains. This stance shares with Confucianism the primacy of reciprocity as a manifestation of jen through an attitude of respect, with the sociometric methodology and application of recommendations made by interviewed characters functioning as forms of Li, and concrete manifestations of de. Doing so in turn strengthens the six core qualities of confidence, empathy, wisdom, acceptance, inner peace, and witnessing (forms of jen). To take one example, acceptance is correlated with less emotional reactivity, better decision-making, greater enjoyment of life, and improved relationships. The purpose is not to extend to imaginary elements the same rights that humans have and require; that is absurd, because the unintended consequence would be a life of metaphorical Parsee broom sweeping. Termites and lice are not given, nor does a cartoon character need, the same rights that humans or even animals do. However, that does not mean that in the context of an interview, we cannot extend to them respect, goodness, and benevolence, characteristics of jen, out of an awareness of the dignity of their expression of creativity, life, and order. This is demonstrated microcosmically within IDL in the acts of respectful questioning, the surrendering of one's own identity in a phenomenological desire for non-filtered clarity, and the identification with, becoming, or taking on the perspective of this or that emerging potential. Macrocosmically, it is demonstrated by the assumption of an attitude of respectful questioning, a suspension of drama and cognitive distortions, and an empathetic identification with the perspective of the individual, group, or position. You know you have done this when you receive validation from the other, that you have either repeated or embodied their perspective. This in no way implies agreement, only respect. Jen is applicable in dreaming and lucid dreaming as a value to guide the perception and response to events and encounters, as well as the type of interactions to aim for. It implies that the basic stance of any dream yoga is to be conducted in a manner conducive to jen, that is, to assume benevolence and goodness and to speak to that, respect it, and evoke it, even in the face of demonic evil. This does not require being loving, peaceful, or kind. It does mean being respectful in the context of a definition of respect that is evolved through triangulation, in consultation with respected others, various emerging potentials and your common sense. In such circumstance,s you are not manipulated by someone else's definition of reciprocity or jen.

Li, or Sacred Action

The second core virtue for Confucianism is Li (lee), which provides a concrete guide to human actions that embody jen by supplying order and intention to generate a social and personal benefit. Li is a system of ritual norms and propriety that determines how a person should properly act in everyday life in harmony with the law of Heaven and provides the principles of social order and the structuring of relationships. As the practical application of reciprocity within Chinese society and relationships which bridges the sacred order of Heaven with mundane human behavior, through Li the secular is sanctified and macrocosmic harmony is grounded socially, culturally, and internally. Because Master K'ung believed a well-ordered society is necessary for human goodness, benevolence, and humanity to be expressed, Li provided necessary structure to relationships, making possible the expression of jen by the proper use of language, expressing a balanced position or middle way between extremes, and identifying the appropriate ways to express humanity, benevolence, and respect in particular human relationships. For example, Master K'ung thought love and reverence were the appropriate guiding virtues for father and son relationships, gentleness and respectfulness for brothers, goodness and listening for husband and wife, consideration and deference were central for interactions between older and younger friends, and benevolence and loyalty to the relationship between ruler and subject. Whether or not these specific relationships remain relevant is overshadowed by the timelessness of the belief that relationships are mediated by the presence, strength, and nature of guiding virtues that are behaviorally manifested. Because he assumed that age reflected experience and wisdom, Master K'ung also taught these qualities, older individuals, objects, and institutions deserved li, or behavioral demonstrations of reciprocity and jen. The practice of altruism necessary for social cohesion could be mastered only by those who learned self-discipline, taught through mastering the manifestation of li over time. For a junzi, concern for propriety should inform everything that one says and does. Li might therefore best be thought of as a type of karma yoga and dream yoga, in that it involves waking up out of the chaos associated with a life not governed by virtue. In addition to structuring relationships, li necessarily structures society, ritual, and life, since there are limits to individuality and every action affects others. Therefore, jen requires that we take these effects into account in what we do and say. Li involves not only ritual, but the etiquette, propriety, and morality with which one performs customary acts in the home or in relationships. As such, it is much broader than our use of the word “ritual,” in that it adds sanctity to any action. This sanctity is a naturalistic reverence for the natural and harmonious order of relationships and life rather than a religious sense of the sacred. Li is an attempt to sanctify all of life, including the mundane and secular. If you can imagine doing whatever you do with a constant awareness of humble reverence, you are approaching Master K'ung's understanding of li. As such, it is a transformative idea, because it is an attempt to bring reverence into the routine actions and relationships of daily life. In traditional China, this sanctifying of daily behavior is expressed in tea drinking ceremonies and mourning, as well as social and political institutions, such as in teaching, titles, and governing, and the honoring of both the deceased and those supernatural forces that govern the world. The sacred and secular realms are integrated through li. In the context of Integral AQAL, Li bridges interior collective values and exterior collective social norms. Through an emphasis on right behavior in relationships, both Jen and Li emphasize the lower right quadrant of Integral AQAL holons, while Integral AQAL emphasizes consciousness and self-development in the upper left. Where Integral is idealistic, Confucianism is conservative and concrete; where Integral emphasizes spirit and consciousness, Confucianism emphasizes behavior and relationship. Of course one can point to many areas in which Integral AQAL emphasizes the lower right quadrant and Confucianism emphasizes the upper left, but as heuristic generalizations, these relationships are true enough. Together, jen and li create a highly cultivated and disciplined person who attempts to behave in accordance with them in every situation and who is motivated by deep care and empathy for people. "To master and control the self and return to li, that is jen.” (Analects 12.1) This person is the junzi, in that they control their actions, impulses and desires in accordance with the demands of li and jen. As such, they exhibit a strong sense of personal power - called te, that compels people to follow their example.

Emphasis on Self-Development

Self-development was not differentiated from collective development the way it is assumed to be in the West. Master K'ung's emphasis on jen as ethical self-discipline created a focus on character-building which engaged the minds of the men who governed China and created her high culture. Government was to not be by coercion but by moral example. The Superior Man was to take on the responsibility of cultivating his own character, including the virtues of righteousness, loyalty, trust, worthiness, modesty, frugality, incorruptibility, courtesy, learning, so that he could be put to the service of the state as a Superior Man. We have seen that the educated elite in China therefore had as their primary obligation and moral responsibility the perfection of themselves to serve as moral paragons. They still do, to this day. In a way that is unfathomable to most Westerners, a communist government is more compatible with the deep-rooted Confucian ethic of China than is Western-style parliamentarian and two-party democracy. The problem with setting standards of ethical behavior for government officials is that they are both difficult to live up to and also complicated to measure. Pretense, authority, and status easily mask immorality and amorality. The teachings of Master K'ung emphasize taking personal responsibility, believing that men are responsible for their actions and in particular for their treatment of others. Instead of blaming Heaven, deities, the State, rulers, ghosts, invaders, bad luck, or fate, Master K'ung asks his students to take responsibility for aligning their character with that of the Superior Man and then to become leaders in family, work, and government. We can see from the autobiography of Xi that he followed that path and was rewarded by one promotion after another. IDL focuses on balancing one's current level of development, with the intermediate goal of bringing people up to a healthy mid-prepersonal level of development, as marked by the elimination of drama and cognitive distortions, and morally, from a movement beyond amorality and immorality, and then on the thinning of self thereafter, which is distinguished by a coalition of governance with interviewed emerging potentials that have proven themselves reliable and trustworthy. Taking too much responsibility increases our failure rate, which means that we learn faster. Consequently, are important survival and adaptive reasons why parents and society demand children and citizens take too much rather than too little responsibility. For example, if US citizens believe they can achieve the American Dream if they just work hard enough, they will not resent elites and blame themselves, not society, if they are unsuccessful. However, problems arise from taking too much responsibility, as the doctrine of karma tends to do. For example, there is no evidence that we choose our parents or our life circumstances and therefore cannot be held accountable for abuse by family, culture, or society, as karma teaches us to be. On the other hand, taking too little responsibility is an even greater problem. To do so means that we disown large segments of our own sense of who we are: what happens to others is none of our business, and we can easily stagnate in ethical degeneracy. Getting this balance right between taking too little and too much responsibility is a lifetime of work, and there is no one right answer. This is one reason why the cybernetic feedback of both internal and external sources of objectivity is extremely important for self-development.

Character Is Determined By De, Virtue

How does one define character? Is character the values that you hold, the principles that you teach, the virtuous nature of what you do, or does it lie in the consideration and respect you show in your relationships? Is it all of these things or is it something entirely different? Master K'ung recognized that character involved all of these, something that he shares with integral approaches to character. He not only emphasized values and the teaching of the nature of character, but virtuous individual behavior and interpersonal conduct as well. Just as he emphasized the causative nature of the internal collective quadrant, so he favored the identification and amplification of those qualities upon which character is based. While for Master K'ung character involved what you profess and do as well as how you treat others, character precipitates from virtues. Of all these four quadrants of the holon of human character, values, in the form of virtues, were most important for Master K'ung. Superior rulership over oneself and others is defined by the possession of de or 'virtue.' Conceived of as a kind of moral power that allows one to win a following without recourse to physical force, de enabled the ruler to maintain good order in his state by relying on loyal and effective deputies instead of involving himself directly or appealing to physical force, which is virtuous. Master K'ung claimed that, “He who governs by means of his virtue is, to use an analogy, like the pole-star: it remains in its place while all the lesser stars do homage to it”.[22] Master K'ung's development of character within the Superior Man was based on the cultivation of de and expressing it in his societal relationships. The fundamental value of de is respect for the social standing of each person and obedience to the laws of conduct governing that relationship. While IDL shares this understanding of the centrality of respect, it applies it to relationships with interviewed imaginary entities, something that most people would never consider either needing or wanting respect, nor would they see any benefit to extending respect to them. Virtues that were important to Master K'ung include self-cultivation, emulation of moral exemplars, study, learning, the attainment of skilled judgment rather than knowledge of rules, personal and governmental morality, understanding of others, justice, sincerity, loyalty, trust, worthiness, modesty, frugality, incorruptibility and courtesy. This is such a broad list that they can comprise a list of objectives of socialization, meaning that simply striving to attain them can make a person responsive to social expectations rather than to their own life compass, which is indeed, what the history of Confucianism largely demonstrates. In contrast, IDL recommends students and practitioners pay attention to the values of high scoring emerging potentials and look for patterns of repeating values among them. While IDL uses the six core values for scoring, these are only guidelines based on the round of breathing. You are encouraged to do your own investigation and develop your own version of de. Like Master K'ung, Integral Deep Listening has a set code of values or virtues. These are the six core processes and qualities. While Master K'ung draws his virtues from tradition and attempts to ground his values in the authority of the ancients, Integral Deep Listening grounds its values in the round of the microcosm and macrocosm. It asks, “If processes were to be assigned to each of six stages of the cycle of a breath, what would they be?” It observes that abdominal inhalation resembles awakening and chest inhalation aliveness, in that extra oxygen beyond that needed to merely sustain life is inhaled. It observes that the short pause at the top of each breath is a balance point between alertness and relaxation and that chest exhalation is both a voluntary and involuntary letting go or detachment, while abdominal exhalation is a mostly involuntary movement into radical “letting go,” or freedom. The longer pause at the bottom of the breath is characterized by an absence of motion and content, or relative clarity. It is the formless well out of which new life emerges. Integral Deep Listening then asks, “Where else do we observe such processes in life?” While the terms may change, something similar describes the macrocosmic round of a day, lifetime, year, project, civilization, or cosmic cycle. In addition, Integral Deep Listening asks, “If these processes were associated with qualities, what would they be?” It observes that wakefulness is negentropy, the irrational evolutionary impulse of life to grow, in defiance of entropy, or the movement via inertia into randomness. This impulse to grow is relatively free of doubt and fear; it is audacious in its confidence that expression can happen and is right and good. This is most fundamentally not a rational act, but a raw expression of life itself. For these reasons, Integral Deep Listening associates abdominal inhalation and wakefulness with fearless confidence. Chest inhalation, which is both involuntary and voluntary, is associated with aliveness, and an overflow of life energy beyond the needs of oneself. As values, this takes the form of both self-serving and selfless action, whether as service or compassion. Consequently, Integral Deep Listening associates aliveness with compassion, although words such as productivity, service and goodness will do. Balance of alertness and relaxation, of yang and yin, wherever they appear in life, is wisdom. On an atomic level the wisdom of that balance is called equlibrium; on a biological level the wisdom of that balance is called homeostasis; in the human holon, that balance is called wisdom. The detachment associated with chest exhalation, unwinding from the day, retirement, and autumn, can be associated with the quality of acceptance. This is not a passive quality; it is an active awareness of preferences, likes and dislikes, and a willingness to observe both in a disinterested, dispassionate way. The freedom of radical surrender associated with abdominal exhalation, going to sleep, death, and the oncoming of winter can also be associated with the quality of peace and the absence of stress. This is also not a passive quality, but rather the identification with contexts that transcend and include stress. The formless openness or clarity of the pause at the bottom of the breath may be compared to dreamless sleep, life after death, and the depth of winter. In that this is a space that is radically “other” than the processes that are associated with the round of life, it can be associated with radical objectivity or witnessing. IDL also experiences it as a space of radical creativity. Notice also that there are negative processes and qualities that can be associated with each stage as well: repression/fear; avoidance-egotism; imbalance-ignorance; attachment-drama; addiction-stress; and obscurity-unconsciousness. In Integral Deep Listening these processes and qualities are not a priori “givens”; each student is required to explore these relationships for themselves and decide if they are indeed accurate outpicturings of innate life processes and values. If not, then they are free to come up with their own. These values are used in two basic ways within Integral Deep Listening. The first is to use as a measuring rod to evaluate the perspective of interviewed emerging potentials in relationship to oneself. If an interviewed emerging potential scores higher than you on one or more of these qualities, what does that mean? If it scores lower than you, what does that indicate? We look for the answers to these questions in the comments of the interviewed characters themselves.[23] Like the teachings of Master K'ung, Integral Deep Listening is grounded in a strong sense of interior collective values, but unlike Master K'ung's teachings, Integral Deep Listening does not appeal to authority to legitimatize them. Instead, it appeals to personal experience, asking students to perform them for themselves and validate them in their own experience.

The Importance of a Moral Education

Emperor Wudi (141-87 BC), set up schools so that all applicants could come and study Confucianism, in what is one of the first and oldest government-sponsored educational systems in the world. Government examinations measured how much the person knew about Confucianism. The qualities of truthfulness, generosity, respect, diligence, industriousness, and kindness were taught in Confucianism and were qualities the emperor expected in government officials. Therefore, Confucian ethics have been fundamental to Chinese governance for over two thousand years, yet Western assessments pretend that it suddenly became irrelevant in 1949, when Mao came to power.[24] Moral education was important to Master K'ung because it is the means by which one can rectify the lack of love, compassion, and empathy in society as well as restore meaning to language. Moral education includes long and careful study of historical classics such as the canonical Book of Songs. One needs to find a good teacher who is familiar with the ways of the past and the practices of the ancients and imitate his words and actions. In addition to the teaching of morality, a moral education also meant instruction in proper speech, government, and the refined arts, including ritual, music, archery, chariot-riding, calligraphy, and computation. While many of these subjects and methods are included and transcended in educational curricula of today, the basic emphasis on morality has largely been replaced with the pursuit of excellence. But Master K'ung's goal was different: to create Superior Men who demonstrate integrity in all things, speak correctly, and carry themselves with grace. NOTES[18] “For tyranny is a kind of monarchy which has in view the interest of the monarch only; oligarchy has in view the interest of the wealthy; democracy, of the needy: none of them the common good of all. Tyranny, as I was saying, is monarchy exercising the rule of a master over the political society; oligarchy is when men of property have the government in their hands; democracy, the opposite, when the indigent, and not the men of property, are the rulers.” Aristotle, Politics, Book III. [19] Roberts, G., Social Credit, Datong Dreams. Unz Review, Dec 7, 2018. [20] Dillard, J. Triangulation, IntegralDeepListening.Com. [21] Haidt, J., (2012). The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided By Politics and Religion. New York: Pantheon Books. [22] Lunyu 2.1 [23] See Dillard, J. (2017) Seven Octaves of Enlightenment. Berlin: Deep Listening Press. [24] “Political Confucianism is a newly emerged school of thought addressing political and social reform in Mainland China. It challenges the current prevalent democratic movement, both inside and outside of China, which proposes governance with legitimacy wholly resting on the ballot. Instead, Political Confucianism advocates the wisdom of “centrality and harmony” contained in Confucianism, especially the Confucian tradition of Gongyang School that flourished in the Han and late Qing dynasties in China. It is aimed at revitalizing Confucianism and reconstructing the politics of the Kingly Way in the modern global context.” Rui-Chang, Wang.,The Rise of Political Confucianism in Contemporary China

|