|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

SEE MORE ESSAYS WRITTEN BY ANDY SMITH

The Pros and Cons

of Pronouns

My View of My View of

Edwards' View of Wilber's View of Views

Andrew P. Smith

Note: The following is an email dialogue I recently had with an acquaintance of mine. For those of you who wonder if this acquaintance is a real person, I can only say that according to Ken Wilber, he canít be. We will see, in the course of this dialogue, why Wilber believes that, and even more provocatively, why Wilber himself may not be real. I will refer to this acquaintance simply as He.

He: Have you seen the extracts Wilber has published online introducing his Integral Math?1 Pretty neat stuff! I thought it was brilliant.

I: Brilliant? Why do you say that?

He: He points out that each of us can interact with others using different perspectives. These perspectives are associated with the different pronouns — I, you, he, she, it, we, they — which are pretty much universal in human language.

I: So?

He: So by taking into account these perspectives, Wilber argues that we can build a universal mathematics, one that is not limited to third person views, as current math is. An integral math takes into account the relationship of the person making a statement to the statement itself. For example, instead of saying x = y, I would say: my first person view is that x = y. If you agree with me that x = y, then your first person view of this equation is equal to my first person view.

I: Does this really make any difference?

He: What do you mean?

I: Does it help us to derive any new mathematical equations? Donít mathematicians assume that their first person view of an equation is the same as that of some other mathematician? Isnít that the whole point of writing a mathematical proof, to bring other peopleís views into line with oneís own? So is it really necessary to add these first person views? It seems to me they always cancel out in the end, anyway.

He: But thatís just Wilberís point! They cancel out in conventional mathematics because it takes a third person perspective. But they donít necessarily cancel out in other formulations.

I: Such as?

He: Well, Mark Edwards has shown that we can categorize literally dozens of views or perspectives, such as my view of your view of me, his view of your view of her, and so on.2 Each of these views, according to Edwards, is representable in a four-quadrant model, with inner and outer aspects and singular and plural aspects. Edwards then gives examples of each kind of perspective, and shows how they can help illuminate our understanding of individuals and societies.

I: Yes, I understand that, but I donít see that it really involves any math. Edwards has shown how each view corresponds to some formula in Wilberís integral math, but the formulas donít seem to me to provide any additional information. They certainly arenít needed to elucidate the views, and itís not clear to me that they can be manipulated in any way to demonstrate something we wouldnít have known otherwise.

He: Maybe Wilber, Edwards or someone else — maybe me or maybe you! — will eventually accomplish something like that.

I: Maybe. But before that happens, I think some problems with this integral math need to be cleared up.

He: What problems?

The four quadrants of Ken

What he thinks, what he says, what he means, and what he wants others to think he means

I: Well, for starters, what exactly is a pronoun? Pronouns are obviously at the heart of Wilberís math; the terms in his formulas all represent pronouns, as do all of the entries in Edwardsí numerous tables. So we better get straight what we mean by a pronoun. But here Wilber clearly fumbles the ball.

He: How so?

I: This is what he says: "A pronoun is not an actual person but a relative perspective that all actual persons can adopt."

He: Whatís wrong with that?

I: "A pronoun is not an actual person." Well, duh! Of course a pronoun is not an actual person. A pronoun is a word. What Wilber surely intended to say here is: "A pronoun does not refer to an actual person but to a relative perspective that all actual persons can adopt."

He: Hmmm...

I: In fact, a few sentences later, he does say that: "The pronouns do not refer to actual people...but to the perspectives..."

He: OK, I see what you mean. Wilber should have been clearer in distinguishing between what a pronoun is, and what it refers to. He was just being a little careless.

I: As someone who writes — what is it heís claiming now, eight hundred pages in six months? — is bound to be.

He: Give the poor man a break! These extracts are only drafts. You arenít even supposed to be quoting from them. This is a very trivial error. In fact, we quite often say things in casual conversation that arenít technically correct, but which are close enough to the point so that we can reasonably expect other people to understand our meaning. For example, I might say that George is a proper noun. Thatís not really correct. George is a person. The word "George" is a proper noun. But everyone understands what I mean when I say that George is a proper noun.

I: Actually, you could be correct in saying that George is a proper noun. Thereís no reason why George canít be either a word or a person. Which is all the more reason to be precise about what we mean.

He: So whatís your point? Do you just want to quibble with Wilber over the meaning of words? If thatís your game, Iím pretty busy now, andÖ

I: Wilber claims to be a philosopher, and philosophy is about nothing if not about meaning. My point is that Wilberís carelessness here hides a serious flaw in his reasoning. Some of his critics might argue that this is a common ploy of his, that he is frequently intentionally careless in order to gloss over such flaws. Iím not going to accuse him of that here. But whether that is so or not, it does have that effect.

He: Why? What do you mean?

I: The flaw is apparent in a false distinction Wilber makes between pronouns and proper nouns. Consider this statement, part of which I quoted earlier:

The pronouns do not refer to actual people — they do not refer to John, Paul, George, or Ringo — but to the perspectives that all proper nouns (John, Paul, George or Ringo) have available to them, universally.

Note first of all that Wilber is again being what we are charitably calling careless. Proper nouns, like pronouns, are words, not people, so they do not have perspectives available to them. What Wilber should have said is: "the perspectives that all people, who are referred to by proper nouns, have available to them."

He: OK. Granted.

I: If we accept that Wilber is being careless here, I think we can agree that the point he is really trying to make is that proper nouns refer to real people, whereas pronouns refer to perspectives. Thatís basically what he seems to be saying, when you get past the sloppy writing. But as soon as that idea is brought out into the light and stated clearly in this way, it becomes obvious that itís false.

He: Why do you say that?

I: Pronouns refer just as much to real people as do proper nouns.

He: They do?

I: Of course! The words "Ken Wilber" refer to a real person — at least Ken says they do. But when I make a statement using those words, then follow it with another statement using the word "he", itís clear from context that this word refers to exactly the same thing — to some person named Ken Wilber. If you donít accept that, you better go back to second grade.

He: So your argument is that pronouns donít refer to perspectives? That they refer to actual people?

I: Thatís a tricky question. Iíll get to that in a moment. What I do claim — and I donít know a linguist who would disagree with me — is that pronouns refer to the same things, the same kind of things, that proper nouns do. The only difference between the two is that proper nouns are more specific. The words "Ken Wilber" refer to a specific person. Pronouns are more general. The word "he" may refer to the person named Ken Wilber, but of course it may refer to any other male person as well. Its specificity in any particular usage is not built into it, as is the case with a proper noun, but arises from the context in which itís used.

He: Hmmm...When you say context, arenít you opening the door to some sense of perspective?

I: None that matters here. Thatís another red herring suggested by Wilberís confused style of writing. Of course we can say that the use of "he" in one sentence offers a different perspective from its use in another, but this has nothing to do with the perspectives of first, second, third-person that Wilber is concerned with. I could just as easily say that the use of the words "Ken Wilber" in one sentence offers a different perspective from its use in another sentence. Or that the use of the words "Ken Wilber" offers a different perspective from the use of the words "Mark Edwards". The critical point, to repeat, is that proper nouns and pronouns, whatever they may refer to, refer to the same kinds of things. It simply is not correct to say that one refers to real people, and the other to a perspective.

He: So what — according to you — do they refer to?

I: That is the interesting question that we finally come to when we clear away all the confusion caused by Wilberís carelessness. This is really the central issue of his integral math.

Are we just perspectives?

Suppose we provisionally accept Wilberís claim that pronouns refer to perspectives, rather than to real people. Iím not saying I do or donít accept this, but letís pretend that we do, and see where it leads us. Since pronouns and proper nouns both refer to the same kinds of things, we must conclude that proper nouns also refer to perspectives, rather than to real people.

He: Interesting! But then how do we refer to real people?

I: Well, it seems to me that if you really take seriously the notion of perspectives, there are no real people. That is to say, all there are are perspectives.

He: Huh?! There is no such thing as actual people? That what we call people are just perspectives?

I: In a very profound sense, yes. Isnít this what Wilber himself says again and again? Consider some of these passages:

The real world is not built of variables over domains whose operations can equal each other in a third person mode, but rather of perspectives of sentient beings whose mutual reflections can resonate with each other.

The universe is built of perspectives.

There is simply no perception that is not a perspective, and therefore no appearance of being that exists other than as a phenomenal perspective.

Thus is a Kosmos built out of perspectives, with all other things, events and occurrences in the Kosmos being generated out of iterations of primordial perspectives...

The universe is built of perspectives. If that is really so, how can there be an I or a real person that has a perspective? Wouldnít it be more accurate to say we are perspectives, rather than that we have them? If everything is in fact a perspective, "with all other things, events and occurrences in the Kosmos being generated out of iterations of primordial perspectives ", what can there be that isnít a perspective that can have one?

He: That sounds like idealism to me. That isnít Wilberís view. He makes this clear when he says:

"nor is this to say that perception creates being, for this implies that perception itself exists apart from something being perceived."

I: Yes, and he continues:

"This is rather to say that being and knowing are the same event within the set of perspectives arising as the event."

It would be idealistic, perhaps, to say that everything is perception, but Wilber clearly distinguishes between perception and perspective. Again, his message is that everything is a perspective. Which, to reiterate, raises the question: who, or what, has these perspectives?

He: So your argument is what? That there is no I, you or he/she?

I: No, my argument is that there are no entities that we call I, you, and so on, that can adopt various forms of perspectives. There are only the perspectives themselves.

Look at it this way. According to Wilber, there are three fundamental terms in an integral math, which correspond to three different kinds of phenomena (using that word very broadly). Consider this formula of his:

1p x 1-p x 2p

The first term, 1p, Wilber says, refers to the phenomenological space in which some event arises; in this case, it is I. I am a space in which some event I have a perspective on arises. The second term refers to the mode in which the phenomenon arises; in this case it is a first person perspective. This is the manner in which I experience or perceive the event. The third term refers to the dimension of existence (a very bad term I would say; better just to call it the phenomenon that arises), in this case, you. This is what is being experienced, or what the phenomenological space has a perspective on.

Thus the formula above means: I have a first person view of your person. Or we could say it refers to my first person view of you.

He: OK.

I: My pointĖmy first point — is that there doesnít seem to be a need for that first term. There really is no such thing as "I" who has a first person perspective. There is just the first person perspective, period. That perspective is "I".

He: So you would just drop the first term?

I: Actually, I would combine it with the second term. Because the second term, which is supposed to refer to the mode or kind of perspective, in fact always refers to the first person perspective. Thatís my second point. I claim that there are no second and third person perspectives.

He: There are no second or third person perspectives? Then how can you refer to me, or I to you?

I: I recognize that there is a first person perspective that is I, and that there is another first person perspective that is you. There are many first person perspectives, and I can refer to any of them. When I refer to you, I may mean a certain first person perspective, in which case I use that term that combines Wilberís first and second terms. We could call it "the first person perspective that you are", or something like that. I may also mean something more than or other than that, such as your physical body or your behavior. Features such as those which I associate with you belong to the third term in Wilberís formula, what he calls the dimension of existence and what I simply call phenomena. Iím not challenging that concept.

He: So now youíre saying that there is something more than just the perspectives. There are these phenomena, such as bodies and behavior.

I: No, because these phenomena are part of my perspective (the perspective that I am) of you, or my perspective of someone else. They are not (necessarily) part of the perspective that I refer to when I say "you", however.

He: But you are denying that I can have, for example, what Edwards calls "my notion of your view of you", or "my notion of his view of them". And so on and so on — all these dozens of possibilities that Edwards has catalogued.

I: Iím not denying that there can be all these different views that might fit into those slots that Edwards has created. What Iím denying is that any of these views are second person or third person in nature. Theyíre all first person.

He: Iím having trouble following you.

I: Letís look more closely at what Edwards says. Itís basically the same thing Iím saying, though as I feel is frequently the case in his writings, he discovers a very significant point without really being aware of its implications. Notice that he hedges in calling these views "perspectives", often using the word "understanding" instead. That is a giveaway that he doesnít really regard all these views as perspectives in the same way that a first person perspective is a perspective. Notice also that in his first sets of tables (4-7), though he uses three terms, one of the terms is always (1-p), or the first person perspective. Whether heís talking about my view of me, your view of me, your view of him, or whatever, the view is always first person, or (1-p) in Wilberís terminology. My point is just that we donít need to use this term, since we understand that every view is always first person.

He: But sometimes itís first person singular, and sometimes plural.

I: Yes, I will come back to that point later. But for now, letís just concern ourselves with the first person.

He: OK, but in Edwardsí later tables (8-15), he does refer to second and third perspectives. There he uses the terms (2-p) and (3-p).

I: Correct, but letís look at what he says about them. He makes the distinction between a direct perspective and a notional perspective. A direct perspective occurs when one person views another, without taking into account that other personís views. Thus I have (or as I would say, am) a view or understanding of you, period. All the views depicted in Tables 4-7 are direct. A notional perspective, in contrast, does take into account the view of someone else. Thus I have (am) a view or understanding of how you view or understand me. Notional perspectives are catalogued in Tables 8-15.

Now there is a very big difference between these two kinds of "perspectives". Edwards identifies the crux of this difference in his description of a notional perspective: " an understanding of such a view occurs when someone imagines how some other person or audience who is present directly perceives him/herself."

The critical word here is "imagine". A second person or third person perspective is literally imaginary. It is not a real perspective in the sense that a first person perspective is. The first person perspective is direct and immediate. It comes to us unbidden, so to speak. We are constantly imbedded in it. In contrast, what Wilber or Edwards calls a second or third person perspective is the result of a thought process, when we try to think or feel the way we think or feel someone else does. We donít do this all the time, of course, and some of us do it much more often than others.

He: Well, one could argue that the first person perspective is also a thought process, at least in part.

I: To some extent, yes. But it is something more than that. And in any case, to the extent that both first person and second/third person perspectives are thought processes, to just that extent what we call a second or third person perspective is really just part of a first person perspective. Which reinforces my earlier point: that there really is no such thing as a second or third person perspective, in the sense of being distinct from, yet very much like, a first person perspective. We could say that what we call a second or third person perspective is part of a first person perspective. Or we could also say that it is part of the phenomena or Wilberís dimension of existenceĖthe third term in his formula. Either statement, I think, is consistent with Wilberís own description of the third person perspective as an "abstraction" from the first person view.

He: All right, but the fact remains that something is going on when we adopt what Wilber and Edwards call a second or third person perspective. And Edwardsí analysis suggests that it can be very useful to recognize that we do this. Itís important to distinguish, for example, between my view of you, and my view of your view of me.

I: I agree. Just as itís useful to distinguish between my view of you and my view of him. There are many things I can have a view of, or be a view of. I just want to keep us clear about how we classify these things. What we call a second or third person perspective is not a distinct mode in which some phenomenon arises, as Wilber would have us believe. It is either part of the universal first person mode in which all phenomena arise, or it is part of the phenomena in the perspective, as "you" and "he" are.

He: Arenít you quibbling a little here? You seem to accept all the categories in Edwardsí tables, which were generated by following Wilberís formula faithfully. Your disagreement seems to boil down to what we call the various terms.

I: My disagreement goes deeper than that. Let me give an example of the trouble one gets into by not explicitly recognizing the differences between first person perspective and second and third person "understanding".

Suppose we want to apply these formulas to lower level phenomena. Edwards, as usual, is only concerned with human-level phenomena. Thatís fine. But Wilber, also as usual, tries to go much further, stating that these perspectives are universal:

The relations among pronouns are relations among sentient beings wherever they arise. They are universal in that sense.

the fact that a matrix of indigenous perspectives eventually delivers the major methodologies already in existence, suggests they are indeed some of the most fundamental, perhaps the most fundamental, ingredients of such a universe.

This is vintage Wilber. Take some observation that seems to apply to humans, then sweepingly claim that it applies to the entire universe. In fact, the second person and third person "perspectives" are not universal. They are pretty much restricted to human beings, and maybe some non-human primates. There is no evidence, and no reason to believe, that most other forms of life ever "imagine how some other organism that is present directly perceives itself", to paraphrase Edwards. Below the vertebrate level, life basically responds to other life through fixed behavior patterns, blind reactions that are programmed to do one and only one thing, regardless of what the other form of life does. Certainly there is no question of the organismís understanding how some other organism views itself. Even most vertebrates probably lack a second person "understanding", and certainly a third person one.

He: You could always argue that behavior patterns have built-in assumptions about what some other form of life will do, which is a kind of second person or third person view. After all, such behavior evolved because it was effective, and itís effective because, most of the time, the assumptions itís based on are correct. A fly sees a shadow, and it takes off. The assumption is that a shadow represents another organism that wants to eat it.

I: Then Iím going to argue that the "perspective" belongs not to the organism in question, but to the evolutionary process that created it. Remember that our own multi-levelled brains allow us to manifest some of the same kind of behavior that lower organisms have. We also tend to duck or flinch or in some other way react negatively when something dark suddenly appears above us. Does that mean we are imagining what some other form of life is thinking? I doubt that very much. I donít think thereís any imagination here at all; itís just pure reaction.

He: Perhaps weíre just not aware of the imagination process, because it occurs on a very low level of our nervous system.

I: What kind of imagination is that? You know, Iím finding this conversation very interesting — and ironic. Iím sometimes criticized, particularly by Mark Edwards, for trying to argue that phenomena we see at lower levels have analogues at our own level. This despite the fact that I back up my arguments with scientific evidence. But when Ken Wilber says a human phenomenon has analogues at every lower level, without providing any evidence at all, you rush to support him. Or at least you donít challenge him.

He: Youíre trying to argue from the lower to the higher. Wilber is going the other way.

I: But reasoning from the lower to the higher is much safer. Wilber himself points out that the nature of holarchy — with new properties emerging at higher levels — implies that not all higher level phenomena will have lower level analogues, while the reverse is true. Besides, Wilber also reasons in the lower-higher direction, as when he claims that even those at higher states of consciousness are imbedded in a context which limits their perspective. He has no real evidence for this. This is sheer extrapolation from postmodern philosophy, but I donít see you or anyone else calling him on it.

He: Well, letís just agree that itís an open question whether all forms of life have second and third person perspectives. I will also agree with you that the second and third person perspectives that we have are different in some ways from our first person perspective. But the fact remains that working with all three of them, their various permutations, seems to open a very fruitful line of inquiry. Which brings us back to Edwards and his analysis of humans. I think his tables are pretty impressive. Do you agree?

I: I like this stuff, and Iíve told him as much. But Iíve also pointed out that I believe there is a much simpler way to represent these relationships.

He: Oh-oh, I think I smell Flatland. Weíre talking about your one scale model again.

Edwardsí intrinsically social individual

I: I would prefer to say that weíre talking about the relationship of singular to plural, because that is the essence of the difference between my model and the four-quadrant one. Recall that I said earlier that there is nothing but first person perspectives. There is no other kind of perspectives in that sense of the word, as second and third person views are not real perspectives, but literally imaginary ones. But there is a real issue over whether these first person perspectives are singular, I, or plural, we.

He: Edwards seems to accept both. He includes both in his tables.

I: Yes, but the big question is the relationship of "I" to "we". What is "we", anyway? Is any "I" also a "we", or is "we" completely separate from "I"? If the latter, who is "we"? If every individual is an "I", who is "we"?

He: Edwards might be interpreted as saying that "I" is also "we". He talks about the "essentially communal nature of individual consciousness".

I: Yes, but heís uncomfortable with the words "we" or "our" in this context. He would like to restrict these words to social holons, and not use them to describe the social nature of individual holons. Thus he claims that "the communal interior of an individual holon is not plural, itís a single cultural I".

He: Do you agree?

I: Yes and no. I certainly agree with Edwards that there are social holons and there are individual holons, and that individual holons have a social or communal aspect to them, as well as an individual aspect. Wilber conflates these two concepts in his four-quadrant diagram, and Edwards is concerned to separate them, to show that they are different features. Actually, I made the same point in an article several years ago.

Where Edwards and I differ is in the relationship of individual and social holons, and this is the essence of the difference between the four-quadrant model, which Edwards wants at all costs to preserve, and the single scale model that I prefer. In the single scale model, individual and social holons are on the same axis or "quadrant". They are part of a common developmental or evolutionary pathway, with individual holons associating to form social holons, and social holons associating to form a new kind of individual holon. In this diagram, the social or communal aspects of individual holons are understood as those features or relationships that lead them to form social holons. So there is no conflation. I donít say that the social aspects of individual holons are social holons. I say that they are the processes that lead to the formation of social holons. For example, our use of language is an example of a communal aspect of individuals, one that leads to the formation of societies — or perhaps more accurately, goes hand in hand with their emergence.

Edwardsí view of individual holons and their communal aspects is much the same up to a point. But since he wants to preserve the four-quadrant model, he depicts the individual (or agentic) and social (communal) aspects in different quadrants, much as Wilber does. Having done this, though, he has no way to distinguish individual and social holons, on the same diagram. This leads him to argue that individual and social holons belong on separate four-quadrant diagrams.

He: I understand all this. And more recently, his inclination has been to draw a four-quadrant model for everything. It becomes not so much a model of existence as an interpretive lens, as he puts it, through which we view existence. My question is, what difference does it make? He has his way of representing things, and you have your way. You both seem to be representing the same things.

I: Well, itís not quite that simple. My assumption, as I pointed out earlier, is that individual and social holons share a common developmental path. There is abundant evidence for this. So though I do distinguish between social or communal aspects of individual holons, on the one hand, and social holons, on the other, I still recognize a very strong relationship between the two. I would say that "I" is also "we". In fact, I would say that most of any "I" is "we". Mark disagrees sharply here. He says that individual and social holons have "different parental holarchies" 3, or what I assume means lines of development, and he thinks he can separate, to a very large degree, the communal properties of individual holons from their existence within social holons.

He: What does all this mean?

I: Letís look at what he says: "the cultural/collective consciousness of the individual is inherent to each life. Itís there from the beginning." Really? Then why do socially deprived children lack it? There are those rare, horrifying, but so illuminating examples of kids brought up in almost total social isolation, who not only canít speak, but havenít a clue about how to relate to other people.

I would say that the potential to develop this consciousness is there from the beginning, with its realization being contingent on developing within a certain kind of environment. This is really pretty obvious, but once you actually state things this way, you realize that the communal aspects of an individual have a strong dependence on the individualís being situated within a social holon. These communal aspects require for their expression a constant interaction between individual and society. This conclusion, in turn, leads you, or ought to lead you, to ask why not represent both kinds of holons on the same kind of diagram. If individuals can only develop fully within a social holon, how can one possibly assert that individual and social holons follow separate developmental paths, or that the path of one can be depicted without reference to the path of the other?

He: Surely Edwards is not denying that individuals interact with their societies.

I: Frankly, I donít know. What I do know is that he explicitly denies that what he calls a personís cultural interiority — the lower left quadrant, the home of values and meaning — is shaped by social interactions:

Wilberís cultural interiority is not inherent to personal identity but comes as a result of interaction with others. This is a definite weakness in his representation of individual interiority. Itís like proposing that light is inherently a particle and only becomes a wave when interacting with other photons. This is not at all the case. We know, in fact, that each photon of light is inherently wave-like and behaves as such in the absence of any other photon. Similarly individuals are innately cultural/communal without any need for further qualification.

I find the notion that "individuals are innately cultural/communal without any need for further qualification" — as though we could develop values and meaning without any interactions with other people — astonishing, particularly coming from someone as experienced in working with others as Edwards is. I find his model for such innate communality — his claim that the individual vs. communal aspects of persons are like the particle/wave aspects of photons — incredible. But that latter idea is not novel. It surely is no coincidence that the one other Wilber critic I know who has stated a similar view, Gerry Goddard, also is aware of the individual/social aspect vs. holon conflation in the Wilber four-quadrant model, and like Edwards, has tried to address the problem within the framework of this model. 4 I regard it as a measure of how desperate some people are to retain the four quadrants that they will assert a relationship like this, comparing an individual to a subatomic particle, without the slightest iota of evidence. Wilber himself has warned against reasoning by such analogies.5

He: So youíre saying that the single scale model is the only way to address both problems at the same time? The conflation problem and the relationship of individual to social holons?

I: That remains to be seen. But this weird particle/wave view is almost an inevitable consequence of trying on the one hand to avoid Wilberís conflation, and on the other, preserving the four-quadrant model. Avoiding conflation means clearly stating that the social aspects of individual holons are not the same thing as social holons. But retaining the four-quadrant model means representing individual and social holons on separate diagrams — since the original four quadrants are occupied with these individual and social aspects, there is no longer any room in any one set of quadrants for a distinction between individual and social holons. But once you make this move, you separate individual and social holons to the point where you no longer easily appreciate that they do develop together. So you have to give individual holons their social properties mostly without reference to social holons. Hence, the particle/wave notion, the idea that people are inherently social, that they donít need society to be social.

In this respect, I regard the original Wilber model as better, though it does suffer from the conflation. I shouldnít have to add that I agree with Wilber, contra Edwards, that "cultural interiority is not inherent to personal identity but comes as a result of interaction with others." Of course it comes as a result of interaction with others. Without such interaction, there could be no language, and without language, how could there be any cultural interiority? The only kind of interiority there would be is what Edwards calls the "existential I", which I would say is a very rare perspective in modern society. Virtually all of our identity, all of our perspective, is of the cultural or social kind.

This, by the way, is not true for all organisms, or all individual holons. We are exceptionally social or communal in our nature. There are other organisms, and other forms of life, which are much less social than we are. Indeed, we are the most social of all organisms, though I would say there are other forms of life, such as cells in the brain, that are just as social on their level as we are on ours — even more so. I mention this, a point I have made before6, because there is a tendency among Wilber and many of his commentators to assume that what applies to us applies in some fashion to other forms of life.

He: The sweeping claims of universality again.

I: Yes. Iím all for identifying lower level analogies of higher level phenomena, but a mistake Wilber and others constantly make is that they donít look for these analogies in corresponding places. Humans, with our societies, occupy one particular stage on our level. The proper place to look for analogies is with holons that are similarly social. Many are not. This really gets back to the distinction I make between stages and levels. If one sees only levels, one tends to assume every phenomenon on one level has some kind of analogy on every other level. But if one sees stages, one looks for analogies only between corresponding stages on different levels.

What the four-quadrant lens doesnít bring into focus

He: All right, so I see your differences with Edwards. You think he doesnít integrate social and individual holons enough. You disagree about the relationship of "I" to "we". But donít you have to concede that his liberal use of quadrant diagrams — the notion of a conceptual lens — reveals a richness of phenomena? Look at all those tables. And in each table, every entry in a row and column corresponds to a distinct four-quadrant diagram. He has generated literally hundreds of categories of data.

I: Yes, as I said before, I like that. But letís remember that what Edwards is basically doing is classifying. Heís identifying a lot of phenomena or perspectives, and giving them names. Thatís a good start, but what we really want to know is how or why these particular perspectives arise. To answer these questions, we need to understand more about the relationships between holons that are associated with these perspectives.

He: Explain.

I: Letís focus on Fig. 8 in Edwardsí latest paper, AQAL 7. This figure is the prototypical four-quadrant diagram, the basic model he uses for all the various views that he later catalogues in the tables. This is the first-person view of the first person holon. He draws a similar diagram for first person views of other holons, and for second and third person views of all kinds of holons.

Look at the right or exterior side of the diagram. Everything that I will say about this diagram could also apply to the left side, but I will restrict the discussion to just the right side, because exterior phenomena are easier to discuss.

Edwards distinguishes between the upper rightĖwhich he calls "my behavior and my activityĖthe doing me" and the lower right — "my social roles and public personaĖthe performing me." Now obviously the act of performing is a kind of behavior, so the question arises, what exactly is the difference between the "doing me" and the "performing me"? A little thought will indicate that the difference lies in what the behavior is directed towards. The performing self directs behavior towards other people — or in more general terms, towards holons on the same stage or level as itself — while the doing self directs behavior towards non-human forms of life — that is, towards lower holons. This is a very important point. Edwards may or may not be aware of it, but his four-quadrant lens canít reveal it, just because using such a lens presupposes separating individual and social holons on separate diagrams.

Now look at just the lower right, the performing self. An obvious question to ask is: performing for whom? For myself? For you? For him or her? For us? For you plural? For them? All of these relationships involve performing, yet in Edwardsí model, all of them are packed into this lower quadrant, without any distinction. Again, there is no way to represent them.

He: This information is in his tables, though.

I: Yes, but the tables are supposed to be rooted in the four-quadrant diagrams — at least, the definitions in the tables are unpacked in these diagrams — and in this respect, these diagrams fail him.

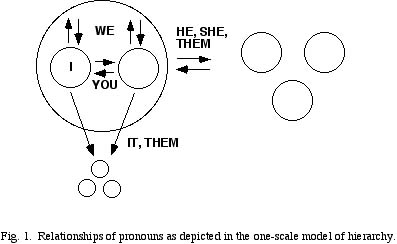

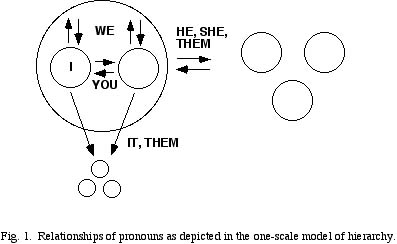

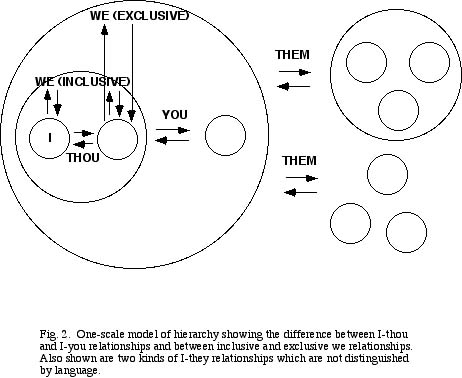

I find that a single-scale hierarchy is not only much simpler, but makes it possible to portray all these relationships. Concentric circles are used to depict higher and lower relationships. Fig. 1 shows all the major pronouns in this way. We can see at a glance what the different relationships between persons involve. I vs. you is a relationship between two holons on the same level that share membership within a larger holon. I vs. he, she or them is a relationship between two holons on the same level that do not share a common membership in that context, though they may in some other context. I vs. it is a relationship between two holons on different levels, with it lower than I.

He: So in this diagram, the I vs. it relationship involves the behavioral "I", while the I vs. you or he, she, them involves the performing "I".

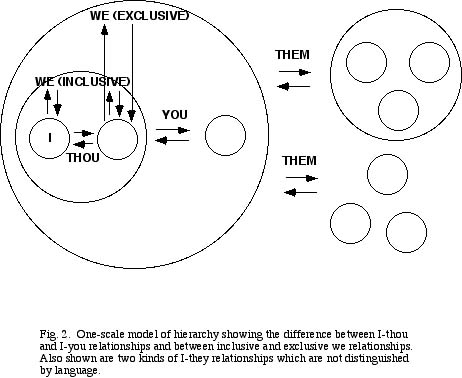

I: More or less, yes, and their corresponding interiors. This is only the beginning, though. The inclusiveness of such a diagram is further shown by the fact that it can deal with relationships that are not identified as such in English, but which are present in some other languages. For example, many languages, such as French, distinguish between two kinds of "you", an intimate or informal version, and a formal version. The intimate form of you is used between two people who have a close relationship, while the formal form is reserved for relationships that are not so close. English used to make the same distinction with the words "thou" and "you", but of course "thou" is now very rarely used, with "you" being called into service for both senses.

In my diagram, the intimate form of "you", or "thou", is that between two holons that share membership in an immediately larger holon, while the formal form is between two holons that share membership only in a much larger holon (see Fig. 2). For example, two people who used the intimate form of "you" might be members of the same family, while two people who used the formal sense of "you" might be members of the same school, workplace, or nation. Thus the degree of intimacy between two individual holons is inversely related to both the size of the social holon including them, and to how much higher it is than they are.

He: Do you think the presence or absence of such a term in a particular language says something about the holarchical structure of the society with that language?

I: No doubt, though the relationship may be complex, and not one I want to get into here.

Another example involves the word "we". In some languages, such as Filipino, there are two forms of this word, an inclusive form and an exclusive form. The inclusive form is used when speaking to someone who is a member of the holon referred to by "we". For example, if you and I are going somewhere together, I use that form of "we" when I talk to you. But if I talk to someone else who is present about where you and I are going, I use a different form of "we", one that refers to a group that does not include the person spoken to. This distinction, too, can be easily represented in these diagrams, because again, the difference is between membership in a smaller, more intimate holon, and membership in a much larger holon. This same diagram also makes the important point that we are simultaneously members in many different groups, some more inclusive than others.

Even further, this kind of diagram can reveal relationships for which perhaps no language has a specific term. Consider the relationship of an individual to a social organization he doesnít belong to. For example, your relationship to some corporation, or to some other nation. How do you refer to that social organization? The most commonly used term is "they". You might call someone at the corporation to get some information, and later tell your friend, "they told me such-and-such". Or you might say about some other country, "what they really want is such-and-such."

In situations like this, weíre really interacting with a single social holon. Why, then, do we use the word "they"? Mostly because we have no better word. To use "he", "she", or "it" seems inappropriate, as we reserve those terms for individual holons. "They" is correct in the sense that this social organization includes more than one individual holon, but it is still a single holon itself. It is clearly a very different usage of "they" from the way we use that word when, for example, we point to several people on the street.

Why do we have no selective word for another social holon, one we donít belong to? Probably because only relatively recently have we recognized that social holons have some kind of existence independent of their members. In the past, there was not such a distinction between a loose plurality of individuals, and a cohesive organization of them. For example, the notion that a business can be treated under the law in some respects as an individual is a relatively recent one.

He: But what about bands, tribes, nations, holons like that? They have long been recognized as more than just a collection of individuals.

I: Yes, but until relatively recently, most societies like that were represented by a single person, such as a chief or king. Relations between nations were to a large extent conducted by interactions between one leader, and his representatives, and another. Itís very different now. Modern Western societies may have Presidents or Prime Ministers, but we all recognize that no one individual can represent such a society in all aspects. Even political leaders in other countries mean much more than George Bush when they refer to America, and when people refer to America in a cultural context, Bush is hardly in the picture at all.

He: Your diagrams show relationships between different pronouns, but they donít distinguish between direct and notional perspectives. For example, the arrows between "I" and "you" could represent "my view of you" and "your view of me", but they could also represent "my view of your view of me", and "your view of my view of you". Thereís no way to tell.

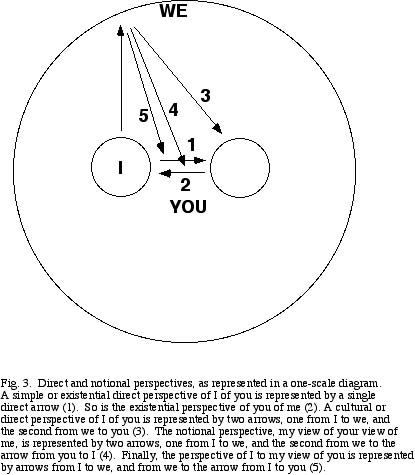

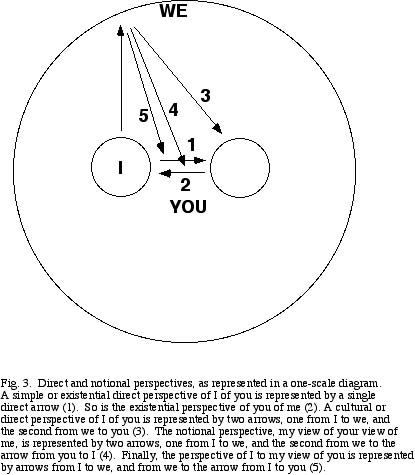

I: The two kinds of relationships can be distinguished. We can let direct relationships be indicated by arrows that point directly from one holon to the other. Thus in Figs. 1 and 2, all the relationships are direct. My view of you, my view of it, and so on. To depict indirect or notional relationships, we use an indirect set of arrows, as shown in Fig. 3. Here my view of your view of me is represented by an arrow from "I" to "we", then a second arrow from "we" toĖnot "you"Ėbut to the arrow between "you" and "I".

Notice that drawing the arrows in this way is not simply a way of allowing us to cram more representational information into a single diagram. The arrows depict relationships that actually occur and are associated with the notional views. In order for me to haveĖor as I say, be — a view of you, it is enough for me, my perspective, simply to be in your presence, and perceive you. But in order for my perspective to include your view of me, there must be a relationship of "I" with "we". Why? Because only as a member of a "we" can I have access to language and other cultural properties from which notional views of others emerge. Another way of putting this is to say that Edwardsí existential /behavioral "I", in the upper quadrants of his diagrams, can never be associated with a notional view. Only the lower quadrants, the cultural/performing "I", can be associated with such a view, and this cultural "I", as I argued earlier, can only emerge from the interactions that create a "we".

He: You said that "I" can have a direct view of "you" without reference to a "we", as in Figs. 1 and 2. But surely a view like that is very unusual. You said earlier that the behavioral "I" interacts only with it, with lower holons. Much more frequently, it must be the cultural "I" that is taking the direct view. I may have a view of you that does not include or take into account your view of me, yet it still involves access to language and culture.

I: Correct. And that can be represented by an arrow from "I" to "we", followed by an arrow from "we" directly to "you". So we really have distinguished three kinds of relationships, which we might call, employing Edwardsí terminology, direct existential / behavioral, direct cultural / performing, and notional. Almost all human perspectives involve the latter two, while other forms of life may be associated with the first.

Notice, however, that Fig. 3 reveals another kind of notional perspective that escapes Edwardsí classification: my view of my view of you. The term "my view of my view" may seem redundant, but it represents another actual perspective. It occurs when I try to look at my view of something objectively, that is, understand how or why I view it as I do. This is the kind of perspective philosophers take, or try to take, when they seek to understand how they understand something. So we can also have "your view of your view", and "his view of his view", and so on. Again, this kind of perspective is only possible because of "we". In fact, it would probably require a higher-order "we"from that needed for my view of your view, though this is not shown in the diagram.

He: So how does all this help us understand how these various perspectives arise?

I: This kind of diagram shows that every kind of perspective is associated with a certain kind of relationship between holons. For example, we have seen that an I-thou relationship involves a relationship not simply between one individual holon and another, but also a relationship between each and a certain kind of social holon that includes both. An I-you relationship presupposes a different kind of social holon. That may seem pretty obvious, but the point is, any society has some characteristic pattern of individual and smaller social holons included within it, and associated with these patterns emerge the various kinds of perspectives. In a previous article I discussed how some mathematicians are beginning to analyze networks.7 The kind of data they obtain, it seems to me, can help us understand how certain kinds of perspectives tend to flourish in any particular society.

The future of integral math

He: Finally — to get back to where we started — what about Wilber's integral math? Does it have a useful future?

I: I think one of the biggest problems — challenges, if you will — facing it is how to create equations as opposed to just formulas. You know, where you have two sets of terms with an equal sign between them? It's pretty hard to have real mathematics as the endeavor is normally understood without equations.

Wilber gives several examples of what he calls equations, each of which is meant to indicate that one person's perspective on some person is the same as some other person's perspective on that same person. The problem is that this is never the case. One first person view is never the same as another first person view. To suggest that it ever could be would seem to violate Wilber's own views (and just about everyone else's) on interiority. Nor is one second person or third person view ever the same as another. Talk about a theoretical form of mathematics!

He: But earlier you talked about how my first person view of x=y was the same as yours.

I: But it isn't! That's supposed to be Wilber's point. Our third person views are the same — if we regard third person views as not part of first person views, but as something abstracted from that, as Wilber does. But our first person views are different. At best, we could claim that one perspective matched a second perspective more closely than did a third perspective. Certainly all of us, in our everyday lives, assume that is the case. But how would we prove this assertion? It seems to me that in the end we would do so by agreeing to flatten out the formulae and just consider third person views, as mathematicians normally do. Ask yourself, when people have a disagreement, how do they settle their differences, that is, in Wilber's terms, bring their perspectives closer to each other? If any kind of settlement really occurs, they usually appeal to some set of facts, which in Wilber's view, are third person views. (Edwards disagrees with Wilber here, for even third person views in Edwards' model have interiority, but since it's an interiority we can't access, it doesn't really matter). I suppose one could use Wilber's formulae to represent this process by which someone comes to understand the same facts as someone else, but I don't see the point.

He: But people don't always settle their differences by appeal to facts. Sometimes they come closer in their views because one or both parties experience a change in their values.

I: All right. But why does that happen? Certainly facts are still a big part of the picture. If you were politically conservative and you become liberal, the change is most likely due to a large degree because of new facts you have become aware of.

He: I would call that a horizontal change. What about a vertical change? Suppose someone who is at orange becomes green? Or green becomes yellow?

I: This SD stuffÖBut facts are still involved. And even if it isn't all about facts, so what? So what if there is a change in values? How are you going to assess these values, except through a third person type of procedure?

It seems to me that Wilber is maybe trying to have it both ways here. On the one hand, he protests that empirical methods are limited, and don't give us a full view of reality. But if we're talking about shared data, what other methods can we use? We can accept that there are aspects of existence that are beyond empirical observation, but how can we represent them in a shared science or mathematics?

He: Edwards would say that empirical methods can be used to measure interior phenomena.

I: I think that belief is based on a misunderstanding of interiority. According to Wilber, the interior is an inner or private face of a holon not accessible to observation of any kind from another holon. It seems to me that interior is in effect defined as an aspect of existence not open to empirical investigation.

He: Edwards disagrees. I don't think he would claim that we can know interiority completely through empirical methods, but he does argue that we can use empirical methods to gain some knowledge or insight about interiority.

I: The question is, when we use empirical methods, what are we really learning about? Consider this plausible scenario. Science will probably some day be able to associate particular thoughts and feelings with certain patterns of nervous activity in the brain. If it can do this--accessed through some kind of metabolic scanning procedure, for example--then this information will become public. It will be possible to know what someone is thinking or feeling as surely as we now can know how someone is behaving, in the sense of making certain physical movements and gestures. It will also be possible to know that person's values--for example, the degree to which she believes in or honors certain ideas as opposed to others. And it will also be possible to know the content of someone's dreams.

He: So you're saying there will be no interiority, nothing not accessible to empirical investigation?

I: No, I'm not saying that there will be no interiority. There will still be interiority, because science will never be able to reveal--at least no science that is remotely imaginable to anyone today--what I or you or she or she experience when thinking particular thoughts or feelings, or believing in some value, or dreaming some dream. Even if I can observe another person's thoughts and feelings through future technology, I still will not know what it's like for her. That is the aspect of any first person view that is inaccessible to any other first person view, and that is what I call interiority.

He: And you claim this view of interiority is different from Edwards' view?

I: As far as I can tell. He claims that behavior is an exterior, but he doesn't define behavior very precisely. For example, thinking is a form of behavior, but is thinking an exterior or interior aspect in Edwards' scheme? I believe it must be interior, because he does say that interpretation is an interior property, and interpretation involves thinking. So does value formation.

He: If I understand you correctly, you're saying that you, Edwards and Wilber all have different views of interiority is.

I: Exactly. Everyone talks about it, but no one really defines it. Now of course one might argue that almost any definition of interiority is acceptable if one uses it consistently, but this is what I claim neither Wilber nor Edwards does. We have already seen that neither of their views is consistent with a definition of interiority based on empirical access. Edwards' view is not consistent with this, because he believes that empirical investigation can reveal information about interiority. Wilber's view is also inconsistent with this, because we have seen that thoughts and feelings can in principle be accessed empirically, yet Wilber considers them interiors.

He: Edwards might argue that his view is consistent with some other definition of interiority.

I: It's my claim that there is no such view. In fact, a careful reading of Wilber and Edwards reveals that each of them has a view of interiority that is inconsistent, in a complementary way, with that of the other. Edwards' view is designed to overcome the inconsistency in Wilber's view, but it does so at the price of introducing another inconsistency which is not present in Wilber. In other words, each sees part of a problem but not the whole problem.

He: Explain.

I: Their differences center on the definition of behavior. This is the key battleground. Wilber believes that behavior includes not just outer action, such as physical movement and emotional expression, but also inner action, thoughts and feelings. This is consistent with the argument I just presented, because all of this activity is accessible, in theory if not yet in reality, to empirical observation by another person. But then he calls all of this behavior interior, rather than exterior. Why does he do this? Because he is thoroughly committed to the view that thoughts and feelings are interior. He recognizes that something about them is not accessible to science--what I'm calling experience-- but does not, apparently, see that their content is in theory accessible. Since thoughts and feelings are interior for him, then in order to be consistent, outer activity or behavior must also be interior.

He. With the end result, that for Wilber, exteriors are only physical structures. That is all that is left when all behavior is moved over to the left quadrants.

I: Exactly. And Edwards correctly sees that this is a problem, that exteriors are not being given their full due. Edwards begins his challenge to Wilber by noting that outer behavior, like physical movement and emotional expression, is an exterior property. It is accessible to empirical investigation. This aspect of his argument I agree with. But Edwards, unlike Wilber, fails to see that behavior also includes thoughts and feelings. At least this is the impression he gives, because as I said earlier, he considers values as interior properties, yet values clearly involve thinking and feeling. Because thinking and feeling are processes that go on inside the organism, and science has not yet developed the methodology for accessing them, Edwards regards them as interior. But he is inconsistent here, for as we have seen, thoughts and feelings are, in principle if not yet in reality, accessible to empirical investigation.

He: Part of them is so accessible. But part of them is not. As you said, the experiential aspect is not. And in fact, Edwards defines the singular interior as the experiential or existential "I".

I: Yes, but his cultural "I" is quite different. He defines that by putting values and meaning in the left hand quadrant. He doesn't say that much of what we call values and meaning belong in the right hand quadrant.

My claim is that the only way to settle this argument in a completely consistent manner is to recognize, like Wilber, that behavior includes thoughts and feelings, and also to recognize, like Edwards, that behavior is exterior. When we do that, all behavior goes into the right quadrants. Not just physical movement and emotional expression, but also the content of thoughts and feelings.

He: Leaving interiors as just experience.

I: For want of a better word. Philosophers use the word qualia. Interiority, as I understand it, is not the experience of anything in particular, but just experience.

This, by the way, is why my one-scale model seems to ignore interiority. It isn't that I don't recognize it. It's that I see it as something very different from any particular exterior quality. It doesn't need a separate quadrant, because it is understood to be associated with every exterior property or holon. A particular value, for example, is not an interior. It has interiority associated with it.

He: I'm beginning to think you're quibbling again.

I: No, the difference is very significant. It's my claim that what gives any thought, feeling, value, interpretation, etc., its specific character is its exterior, not its interior. The interior is just the experience of that specificity.

As I have argued before, this is easiest to see with a very simple experience, like the sensation of red. There is clearly an exterior aspect of this sensation; neurophysiologists can explain the color to some extent in terms of processing of light stimuli by certain neural pathways. This explanation accounts for the specificity of red. We can explain, in terms of neurophysiology, why red is different from blue, for example, What we can't explain is why we have the actual experience of red or blue. This is the interior, and in my view, it is not a specific quality at all.

He: This has been a rather long digression. We started out debating whether integral math had any real usefulness. You argued that it probably didn't, since first person views could never really be equal. Your claim is that differences between first person views are always settled ultimately empirically, even when values and meaning are brought into the picture. I think I see a problem, though. If all content of the mind is in principle open to empirical investigation, and interiority is just an experience, then why can you see no possiblity of a--

I: This has been a very stimulating discussion. Gotta go, though.

He: One last question. So you see no future for integral math?

I: I will just say I have no idea where it's going.

He: Now Ken, I'm sure, can agree with you there.

Footnotes

- Wilber, K, (2003) Excerpt C: The Ways we are in this Together. Intersubjectivity and Interobjectivity in the Holonic Cosmos wilber.shambhala.com See Appendix B. An Integral Mathematics of Primordial Perspectives. All quotes from Wilber are taken from this.

- Edwards, M. (2003) Through AQAL Eyes, Part 7. "I" and "Me" and "We" and "Us" and "You and "Yous". Sorting out Kenís Holon of Mixed Perspectives. http://www.integralworld.net/edwards8.html Unless otherwise noted, all quotes from Edwards are from this.

- Edwards, M. (2003) Through AQAL Eyes, IV. Where Ken Goes Wrong on Holons. http://www.integralworld.net/edwards8.html

- Goddard, G. (2000) Holonic Logic and the Dialectics of Consciousness http://www.integralworld.net/goddard2.html

- Wilber, K. (1989) Eye to Eye (Boston: Shambhala)

- Smith, A.P. (2001) Different Views www.geocities.com/andybalik/Hargens.html

- Smith, A.P. (2003) Small World, Big Cosmos www.geocities.com/andybalik/network.html

|

Andrew P. Smith, who has a background in molecular biology, neuroscience and pharmacology, is author of e-books Worlds within Worlds and the novel Noosphere II, which are both available online. He has recently self-published "The Dimensions of Experience: A Natural History of Consciousness" (Xlibris, 2008).

Andrew P. Smith, who has a background in molecular biology, neuroscience and pharmacology, is author of e-books Worlds within Worlds and the novel Noosphere II, which are both available online. He has recently self-published "The Dimensions of Experience: A Natural History of Consciousness" (Xlibris, 2008).