|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

SEE MORE ESSAYS WRITTEN BY ANDY SMITH

IS GOD IN

THE GARBAGE?

A Critical Appraisal

of Adi Da's Philosophy

Andrew P. Smith

"The Dawn Horse Testament…is one of the very greatest spiritual treatises, comparable in scope and depth to any of the truly classic religious texts. I still believe that, and I challenge anybody to argue that specific assessment."

-Ken Wilber[1]

Can both of these views of Adi Da be correct? Can he be both a saint and a sinner, a highly evolved person [with] some very serious human character flaws?

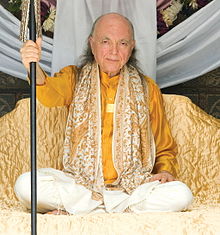

Of all the men and women claiming to be gurus who emerged in the West in the 1960s and 1970s, none has evoked a wider range of feelings, opinions and interpretation than Franklin Jones, at that time known as Bubba Free John. Indeed, he may go down in the history of spiritual seekers as one of the most controversial figures of all time. Man of a thousand names—I believe Adi Da is the current one—he was once considered by many (and still is by some) to be the most highly evolved or realized person on the planet. As evidence for that, his supporters point not simply to the dozen of self-published books in which he claimed to lay out a radical new teaching, but the magnetic effect his immediate presence had on his followers, some of whom—like Ken Wilber and Alan Watts—were and are highly sophisticated scholars and seekers themselves.

Adi Da Samraj, 2008

Adi Da Samraj, 2008

To many others, however, Adi Da is one of history's great frauds. His teaching methods—involving an unusual mix of authority and liberty, ascetic practices punctuated by wild orgies—became the focus of media attention in the mid 1980s,when the revelations of former disciples began to suggest a pattern of widespread and intentional abuse. Women came forward claiming they were forced to become sexual slaves, making themselves available for Jones' needs. Others testified of pressure to donate all their money and possessions to Jones' organization. There were complaints of being discouraged, if not forbidden, from leaving the group. The emergent picture of Da was as just another cult figure, using his charm and his words to satisfy his desires for sex, money and power.

Can both of these views of Adi Da be correct? Can he be both a saint and a sinner, a highly evolved person who nevertheless has been unable to overcome some very serious human character flaws? Ken Wilber thinks so, and in fact uses Da as Exhibit A in his case that spiritual development is not necessarily even, but evolves through a number of different streams, with progress in some often greatly surpassing that in others. In this view, which resonates very closely with my personal experience, it's quite possible for someone to be profoundly intimate with a higher state of consciousness, while remaining relatively much less developed in other areas of life. Indeed, given how difficult the process of meditation is, we should perhaps expect such inconsistencies. As Castaneda's don Juan said, this path makes one more vulnerable, more susceptible to the demands and pressures of ordinary living. How much greater are these pressures on someone who would try to show others the path to these higher states?

That being said, I don't find Wilber's explanation—as sensible as it is—entirely satisfying. Adi Da, after all, long ago claimed to have finished his spiritual journey, arriving at or a realizing a state in which:

I noticed that 'experience' ceased to affect me. Whatever passed, be it a physical sensation, a vision, or a thought, ceased to involve me at all.[2]

Taking him at his word, I don’t see why he should have had any trouble at all in changing his behavior when it became clear that such changes were needed if he were to continue his stated aim of bringing enlightenment to others. Nor am I swayed by the argument that the cosmic consciousness which, according to him, descended into his body-mind at birth, simply made a bad choice, and became stuck with a man with some serious problems, which said consciousness, upon rediscovering itself, may have no longer identified with, but neither had any power to alter. The Franklin Jones who existed before his enlightenment, about which we are given quite a bit of information, does not strike me as an exceptionally difficult vessel in which to carry the consciousness of God (given that anyone can carry it, an issue I will take up very shortly). Fallible and imperfect like any other man, for sure, but not, it would seem, a particularly dangerous or a particularly foolish individual. Those characteristics of Jones emerged only after he claimed to have realized God, and became accepted as a teacher.

So the question remains: is it really possible for someone to develop this unevenly? The entire issue, of course, rests on the assumption that Da has or had contact with a very high state of consciousness, to a degree very rarely found in others, and this is what I want to examine here. I have never met Adi Da, and can't judge the impact of his immediate presence on others. To those who found value in this personal contact, I can say nothing. But his written words, which have impressed Wilber and quite a few others, are there for anyone. What evidence in them can we find for a man of exceptional realization?

I am the Way

The Dawn Horse Testament, as the quote from Wilber above suggests, is usually considered one of Da's best books. It not only contains a fairly detailed presentation of his ideas, but is written in the kind of language and style one usually associates with the great Oriental classics of the past. Unlike standard Western philosophy, which rather intentionally erects some barriers between author and audience, there is a directness in Da's writing here, an attempt to speak right to the heart of everyone. The treatise begins with a statement of purpose, the goal of both teacher and student:

I am here to give you visions of 'I am.' If you realize God as 'I am', you will realize your self, as you are. Even I am only you, as you are, displayed before you, appearing to be an other, until you recognize me and awaken from the illusion of your conditional self.[3]

Da is obviously using the term "I" not in the sense that it is ordinarily understood—as a specific individual person, separate from others—but to refer to a state of being in which all sense of alienation and separateness has been transcended, in which one experiences a complete oneness with all of existence. This is a much greater and glorious I, and by using the term in this way, Da is presumably trying to shock the student, who comes to the teaching with the more traditional understanding of "I", into comprehending the much vaster possibility open to him.

This is not an original idea or approach, as anyone at all familiar with spiritual literature understands; Da is following a very old and venerated tradition in using "I" in this manner. The problem, though, is if you adopt this approach, you have to be consistent. You can't use "I" in some places to mean the all-embracing cosmic consciousness, while in other places intending it in the more conventional sense as the ego or body-mind of a particular individual. Yet Da does in fact seem to do this. Consider this passage:

I am here to Complete the Great Tradition of mankind. I Am the all-Completing Adept, the First, Last, and Only Adept-Revealer (or Siddha) of the seventh stage of life. I Am the seventh stage Realizer, Revealer, and Revelation of God, Truth, and Reality…I Am the Ultimate Demonstration (and the Final, or Completing, Proof) of the Truth of the Great Tradition as a whole. Until I Appeared, there were no seventh stage Realizers within the Great Tradition of mankind. I Am the First and the Last seventh stage Adept to Appear in the human domain (and in the Cosmic Domain of all and All). It is neither possible nor necessary for another seventh stage Adept to Appear anywhere, because I have Accomplished My necessary Work everywhere.[4]

This passage, to me, reads as a statement not about, or at least not entirely about, some all-transcendent consciousness, but about Franklin Jones, a specific individual. For if "I" is to be understood as a cosmic identity, how can it refer to a "realizer within…mankind"? How can it be equated with an "adept" that can "appear" anywhere? If "I" is beyond all human concepts, including those of space and time, how can it be "the final, or completing, proof", "the first and the last" of anything?

Now there is a limited sense in which any genuine teacher may exist as two kinds of "I"s (the extent of these limits will be discussed a little later). On the one hand, he may be realizing a higher state of identity beyond his individual nature; but on the other hand, he does live and act in the ordinary world, and in some situations has to be related to in this way. But the above passage (and many others like it to be found in Da's works) blurs this distinction, and it seems to me is very likely to confuse followers. It sends the message that the individual body-mind of the teacher is what is to be sought—and since one individual body-mind can hardly become another (at least not in my experience, and surely this is not goal of the spiritual path), it encourages a worship of something external to the self, rather than a realization of something that transcends the self. In other words, it creates a cult, a charge frequently leveled at Da by his detractors.

One criticism of passages like these, then, is that they represent bad teaching—they have the potential to lead students in the wrong direction. But what does such writing say about the author's state of being? To many of Da critics, the above passage is evidence of a rather raw, untranscended egotism. Da appears obsessed with the fact that he has not only realized a very high state of awareness, but that he is the only person in the history of the earth to have done so. If he were really completely realized, would he constantly refer to himself the man as something special, glorifying the particular body-mind that had transcended itself? Would there be any necessity for doing this? If he no longer identifies with an individual body-mind, why should he care whether others recognize this body-mind as having accomplished something no one before him has? Shouldn't the power of his insights, if they are genuine, be sufficient to convince others to follow him?

This may be a valid criticism, but the problem actually goes much deeper than this. One could always give Da the benefit of the doubt and argue that he's simply being truthful—he really is the most highly evolved person of all time. And since he is completely beyond and unaffected by ordinary human thinking, feeling and experiencing, he has no need, as others might, to appear modest and humble about this. (As he might put it, that's just another form of seeking). He's just telling it like it is, period.

But there is precisely the nub of the problem: how can that be the way it is? How can someone who has realized the highest state of being even have any connection with any individual human being? How can any being, at one and the same time, be identified with all of existence, and yet also be associated with one particular form of lower existence? This, to me, is one of the most obvious, critical and yet least recognized flaws in Da's philosophy (though he is hardly alone in falling into this error).

To appreciate this problem, we have to have some understanding of existence as a series of levels. Da's teaching itself conveys that point, which I will discuss later, but as most people familiar with his works will be aware, Ken Wilber has gone much further with the idea. Wilber has developed a hierarchical model of existence in which each level transcends and includes that below it (Wilber 1995). The hierarchy or holarchy (nested hierarchy) begins with atoms, molecules and cells, passes on to organisms, including human beings, and extends to still higher forms of existence that transcend the human level.

In Wilber's model, every form of existence, or holon, has both an external form, such as the body of an organism, as well as interior experience, or consciousness. Given this view, we might well ask how any particular holon, such as a human being, is able to access several different levels of consciousness—for example, the ordinary state as well as higher states (and also lower states). Wilber has addressed this question at length, making distinctions among such terms as structures, states, levels and the self-system (Wilber 1998, 2000; see also Smith 2000a). However, it seems to me that we can bypass a lot of this discussion, and just make the point that there are two answers to this question, a strict one and a loose one. The strict answer is that no holon can access more than one type of consciousness. For example, while it is true that human beings regularly descend into sleep (which I, though apparently not Wilber nor Adi Da consider a lower level of consciousness), the "I" present during sleep is not the same "I" present during the waking state. This "I" identifies with a different set of brain structures and activities, and thus represents a different exterior as well as interior holon. Likewise, while some human beings may access higher states of consciousness, the "I" in this state is also not the same as that in the ordinary state. So strictly speaking, it simply is not possible for a holon to access more than one state of consciousness, or interiority. What really happens is that the sense of self moves from one state to another, in the process coming to identify with a different holon. I think Wilber would agree with this.

This strict interpretation of the relationship of holon to interiority, however, does not rule out the possibility of a higher state of consciousness being associated (as opposed to identified) in some manner with a lower form of existence. We can imagine an individual who identifies with a higher state of consciousness, but who is still associated with the physical body of a human being. This person would not have the ordinary state of consciousness that most people have, including the identification with thoughts and feelings, but that does not preclude the possibility of his functioning much as though he did. This type of double identity is commonly referred to in the spiritual literature as "in the world, yet not of it." It is the association with a particular individual body-mind that keeps the person in the world, but it is the identification with a higher-order state or holon by which he realizes an existence that is not of the world.

However—and this seems to be much less commonly appreciated—there are almost certainly limits to this kind of relationship. That is, while a higher consciousness may be associated with a lower form of life, the degree to which the lower is below the higher—the holarchical distance, so to speak, between higher and lower—can't be indefinitely great. Why not? Consider the situation on lower levels of the holarchy. Is it possible for an atom, say, or a molecule, or a cell to be associated with a higher level of consciousness, such as that of a human being? If it were possible, then a human being, even while remaining in the ordinary human consciousness, should be able to maintain an association with a particular atom, molecule or cell. Even as I move about in a world incomparably beyond the comprehension of my individual cells, I should be able to communicate with the latter, by remaining in some kind of association with one of them. The situation is exactly analogous to that of an individual who identifies with a transcendent state of consciousness, but is still able to function in and relate to the ordinary human world.

To the best of my knowledge, there is no evidence for this kind of relationship. There may be occasional reports of people claiming to have experienced their individual cells or even molecules, but quite apart from the dubiousness of these claims (I seem to notice that the descriptions closely match the person's intellectual concepts of what a cell or a molecule looks like)[5], it does not seem that the person can function or be aware of existence on both levels simultaneously. That is, while I don't entirely rule out the possibility that a person might have an experience in which the level of a cell within the body is realized, I think she would have lose ordinary consciousness to do this.

This is not to say, however, that human beings can't maintain any kind of association with forms of existence lower than their own. We are able to communicate to some extent with other organisms, as well as with very young and less developed members of our own species. The reason we can do this is because even though we are aware of a world beyond their understanding, we still maintain a connection with lower-order holons within ourselves which exist on the same plane of existence as these lesser developed forms of life. Thus we can communicate physically and perhaps emotionally with a baby, or a dog. We can move and feel in ways that they can relate to. When we do this, we are in their world, yet not of it; we have an association with it, yet an identity beyond it.[6]

In conclusion, examination of the levels of existence we are most familiar with suggests that there are definite limits to how far below its own position of identity a holon can maintain some meaningful connection with other holons. Without going into details, which I have discussed elsewhere (Smith 2000a), I believe that this limit is one full level of existence, as I define levels. That is, an atom in principle might be able to identify with a cell of which it is a part; a cell in principle might be able to identify with a very simple organism of which it is a part.[7]

If we apply this reasoning to higher levels of the holarchy—and in the absence of any direct evidence against it, I see no reason why we shouldn't[8]—we come to the conclusion that while human beings may be capable of identifying with a level of existence beyond our ordinary one, it's very unlikely that they could identify with any levels beyond that. That is, to identify with such levels, one must go so far beyond our ordinary consciousness that there could be no awareness remaining of an association with a particular individual human body-mind. Some support for this is offered by the reports of mystics apparently losing all touch with worldly existence in certain states (Underhill 1961; O'Brien 1964; Peers 1989; Furlong 1996), though there are of course other interpretations of these reports.

In any case, the point I want to conclude this section with is that any state a human being identifies with, while still able to function as a human being in relationship to other human beings, strikes me as a relatively low one, on the vast cosmic scale. If Adi Da can perform as a teacher and in other ways as a recognizable human being, I don't see how he could be in touch with the highest possible level of existence. If he is, then this highest level is not so very far away after all, and the cosmos according to Da is a much poorer place than many of us have been led to believe.

"The inevitable signs that will and must appear"

In a recent interview conducted by Frank Visser and Edith Zundel, Ken Wilber was asked how his writings, and particularly his model of holarchy, answered questions such as: "what happens to beginning meditators, what ordeals do advanced meditators have to face?"[9] I can't imagine a more important issue for anyone writing about spirit to concern himself with, but Wilber dodged it:

the way that I work is to try to provide the most generalized map possible, because the specific details can only be filled in by concrete practice, usually with an experienced guide in a particular tradition. The same is true whether studying Zen, cooking, gardening, mathematics, or car racing. It would be silly of me to try and give all those details, when most of them are experiential, not theoretical.[9]

I find this response of Wilber's quite curious. If he were a world authority on cooking, I imagine he would have quite a bit to say about experiences such as the colors, tastes and aromas of various foods. The fact that these are all private experiences, that there are a huge number of different kinds of these experiences, and that individuals may differ significantly in the nature of these experiences, doesn't mean that they can't be the subject of some fairly general discussion. The reason they can be, of course, is because all of us share certain nervous system structures, which set some broad limits on our sensory experiences, and ensure that there is a great deal of commonality among them. If one accepts the premise that the nervous system is also involved in some way in meditation—and Wilber does, as I do—it's reasonable to believe that there are also limits and commonalities, albeit perhaps broader ones, on the kinds of experiences we can have as we meditate.

Even if Wilber wanted to confine himself to purely theoretical, non-experiential matters, however, there's still an awful lot he could say about cooking. He would surely write at great length—and in great detail—on where food comes from, how it is prepared and cooked and served, and so on. Obviously, it's more difficult to describe experiences of a higher state of consciousness, when we haven't all shared them as most of us have shared the sensory experiences of food, but as in the latter example, that still leaves room for plenty of work that is both theoretical and concerned with details. To take one example I have discussed in detail elsewhere (Smith 2000b, 2001c; see also below), there is much to be said about the role of energy in meditation, a theoretical issue that is greatly informed by the details of individual experiences. These details lead to some very fundamental and I believe universal generalizations.

Be that as it may, Wilber has a right to choose what he writes about. He has never claimed to be a teacher, and has no obligation to provide any specific information that might help meditators. Adi Da, however, does claim to be a teacher, so he does have such an obligation. If he is to have any credibility in this role, at least with me and I would hope with others, he has to confront such questions. How does he respond?

The Dawn Horse Testament, which Wilber admires so greatly, would seem to be a good place to start. But I had to read quite far into it—past pages and pages of Da's personal history, and generalities about his system—before there was any mention of such details, of what meditators are actually supposed to experience (beyond, of course, the oneness with existence of the final state). In fact, I was nearly halfway through before Da even got around to explaining what meditation, according to him, is.

The section began with Da's drawing a distinction between two kinds of experiences or perceptions that human beings have—direct, sensory perception and conceptual thought. Like almost all of Adi Da's work, this point is not original—the distinction goes back at least to Descartes, and is widely if not quite universally accepted by philosophers today[10]. But again, like much of his writing, the distinction is an important one, and is explained fairly clearly. Having made it, Da then goes to great lengths to emphasize that meditation should focus on the former:

The effort to avoid or escape conceptual thinking…is a futile strategy…the effort to stop conceptual thinking only intensifies the self-contraction…conceptual thinking…is truly transcended only through the real ordeal of self-observation…and radical transcendental intuition of the native condition…in and as which the body-mind-self and all of its conditioning relations are arising…

You can transcend the conceptual mind…by observing, understanding, and transcending the act of self-contraction, to the degree that you relax into simple, experience (or merely perceiving and feeling)…you can transcend all perceiving…by utterly not knowing.[11]

As these passages imply, a key term in Da's teaching is what he calls "self-contraction". According to him, this is the fundamental problem that meditation has to overcome:

This primary activity, this contraction, is the root and the support and the form of all the ordinary manifestations of suffering…this contraction, this '"avoidance of relationship" is, fundamentally, a person's continuous, present activity.[12]

Da, and his remaining supporters, seem to believe that this concept of self-contraction is a unique and original aspect of his teachings, an idea not found in any of the spiritual classics. That may well be true, but is it necessary? In the above passages, Da draws a distinction between, on the one hand, stopping thought, and on the other hand, such processes as self-observation, relaxation, simple experience, not avoiding relationship. In my experience, all of these processes, including stopping thought, are the same—or if one likes, we could say they are different facets or views of the same process. To do any one of these things is to do all the others. It may not always appear that way to the beginning meditator, who at one point may have the experience of trying to stop some thought, at another point trying to relax her body, at another point being aware of her surroundings, at another point realizing a connectedness with others, but anyone who proceeds very far on the meditative path, I submit, will soon realize these are all of these experiences or efforts occur together. At that point, distinction is no longer made, and the experience of meditation is the experience of doing all of those things simultaneously.

I agree very much with Da that the root of it all is "a person's continuous, present activity"; this very nicely summarizes what the mediator is trying to transcend. But because of numerous interconnections among different parts of the body-mind, it's quite possible to transcend this activity by focussing on a single aspect of it, such as conceptual thought. In Gurdjieff's teachings, with the emphasis on different centers in the brain, this point is made especially clear (Ouspensky 1961). Virtually every activity of a person involves thinking, feeling and movement, and by trying to stop (or observe—again, it's the same process) thought, one transcends all other aspects of the activity as well. The body is so constructed that virtually no movement, for example, can occur without some thought and feeling being generated as well—even the slightest movement is preceded by some desire, and accompanied by some thought, as anyone with long practice in self-observation can attest.[13] Thus one can't stop the thought without also transcending the movement and the desire. An approach through any one faculty leads to all of them.

So while I find Da's description of the meditative process fairly accurate—and in basic agreement with the way many, many other people have understood the process—the notion of self-contraction seems to me to be excess baggage. It simply isn't needed. Perhaps he means it as a general term that covers all the different manifestations that are being transcended as one meditates—fair enough. But as a guide to a beginner, I believe it's likely to be more confusing than helpful. It isn't necessary to go looking for self-contraction; it's only necessary to stop thoughts as they arise. If one does that, simple experiencing and all the rest will follow.

What about the experiences of meditators? What does Da say here? In The Dawn Horse Testament, not a great deal that strikes me as very specific, and what he does say, again, is for the most part not original. He talks a great deal about "energy currents" moving down and up the body, which are experienced

By breathing and feeling the Divine Energy in the frontal line of the body—Down through the head, then the region of the throat, then the region of the physical heart, then the solar plexus and abdomen to the bodily base…When this descending practice is full, engage the circle in the ascending or spinal line, calling on Grace at the "ajna" door (or the brain core, deep behind and above the brows).[14]

There are many other passages like this scattered throughout the book, which describe how energy moves through various paths or centers of the body (particularly the heart and the brain), and relating these movements to various stages of awareness. Anyone familiar with the Hinduist gurus that were a major influence on Da will recognize the similarity of these energy currents to kundalini, the so-called snake of power that the meditator is to become master of. Da may position them a little differently, but I find the overall idea very much the same.

How accurate or useful is this idea? In my experience, the meditator can indeed feel energy flowing up and down the body under certain circumstances. But I would describe it a little differently from the way Da and his teachers have. In the first place, it is not nervous system-associated energy, passing directly through the brain and spinal cord. It is chiefly muscular tension energy, which is gradually released as one becomes more aware. As pointed out earlier, one aspect of meditation is relaxing the muscles of the body, and as this is done, energy that was trapped in wasteful tension in these muscles is released. As it is released, the muscle of course feels different, and the result is sometimes the experience of a wave of release that can travel up and down the body, particularly the musculature of the back (which has the largest muscles, and which is most frequently the site of excess tension). It may appear to be moving through the spinal cord, and later to the top of the brain, but in my experience it is largely if not entirely a surface phenomenon.

If one is meditating in stillness and quiet, conditions under which one is generally maximally aware of inner sensations, it's easy to become preoccupied with this feeling. One may make a big deal out of it, mostly because there isn't much else going on. But if one is meditating in the flow of life, the movement of energy has many other, much more interesting, manifestations. We gradually learn that everything we do affects both the level and the quality of our awareness, and that this happens by altering the movement of energy through various centers of the brain. We experience these movements not as physical passages through a series of channels or chakras, but as rapid, dynamic changes in our thoughts and emotions. This is where ordinary life and its demands interface with the higher life and its demands, because both compete for the same energy.

As I have discussed in detail in my book Illusions of Reality (Smith 2000b), there are in fact several important relationships between meditation, awareness and energy which I believe constitute universal principles. These include:

- meditation is a process of gaining energy; this gain in energy always exactly parallels the increase in awareness;

- we gain energy by stopping thoughts; every thought requires energy, and when we stop a thought, this energy becomes available to us;

- the available energy is stored in the brain, first in a temporary or labile form, which is accumulated relatively rapidly but which can be lost (as when the body requires energy for its activities); then much later and more slowly in a permanent form which is not lost;

- the rate at which we gain energy through meditation is normally linear, and for any particular activity we are engaged in while meditating, constant;

- the rate of energy gain differs when we are engaged in different activities while meditating; it's greatest when we are still and quiet, and least when we are engaged in physically demanding activities, such as walking, running, etc.;

- under conditions in which we are regaining a level of energy previously attained and lost (because the energy was only temporarily stored), the rate of gain is not linear but asymptotic, and may for short periods of time greatly exceed the fixed rate at which a new level of awareness can be attained.

Though these principles are all quite general, they were derived from years of meditating under many different conditions, that is, while engaging in many different kinds of activities. Thus I think they provide a good example of how a theoretical understanding can be extracted from "experiential details". These details, the specific thoughts and impressions that occur during meditation, are going to vary greatly from individual to individual as well as from time to time for any one individual, and really are not relevant to any other individuals. But they make up patterns that are not simply of great theoretical interest, but are critical to any meditator, as they determine what, when, where how and why we do the things we do.

I have found no information like this in any of Da's works. The Knee of Listening is a spiritual autobiography, containing a fairly detailed account of his years prior to the moment when, so he says, he realized enlightenment. What does he describe here? Visions of religious figures; acute pains in parts of his body when a chakra or energy center "fell off"; the feeling that his body was taken over by his teacher, among other things. These are the kinds of phenomena so many people want to hear about, and apparently believe are typical fare on the way. In my experience, they aren't. They are much more likely to be the product of an overactive, and wishful, imagination. More typical experiences are crashing, when one drops through an enormous range of awareness levels in a very short period of time, experiencing states one previously ascended through; greatly expanded sensory, emotional and mental experiences, triggered when huge amounts of meditatively accumulated energy suddenly flow into certain centers in the brain; karma chains, in which we observe very clearly how any action is accompanied by certain thoughts, which lead to still other actions and other thoughts; confusion, when one has no idea where one is, what one is doing, or even who one is; and the theater of selves, when one identifies simultaneously with several different personalities, who are often in great conflict with one another.

On what basis can I assert that these experiences are genuine? Well, for one thing, some of them interface with ordinary experiences that can be verified (unlike, for example, visions of the Virgin Mary or the feeling that someone else is occupying your body). For example, the amount of energy that we lose when we crash or experience a sudden decrease in awareness correlates very closely with ergonomic measurements of the amount of energy required for the particular activity we are doing at the time—the more energy required, the greater the loss of awareness (Smith2000a,b). The greatly enhanced experiences of the world do not offer visions of something no ordinary person can see, but just much clearer or stronger visions of what everyone sees. The existence of multiple selves or personalities, again, is not a secret. It's been commented upon by numerous psychologists and other cognitive scientists (Minsky 1985; Berne 1996; Ramachandran 1998); it's just something that ordinary people are very infrequently aware of.

Perhaps most important, however, these experiences are very reproducible, and with persistent observation can be shown to have definite causes. They occur in certain situations, as a result of certain practices, certain activities, and certain stimuli. By observing these phenomena again and again and again, one comes to understand these conditions very intimately. Surely if meditation is a teachable or communicative discipline, if one meditator can say anything at all useful to another, such reproducibility is essential.

Da's experiences, however, seemed to be unpredictable, occurring at any time, with very little relevance to what came before or after. The ultimate example of this is his sudden enlightenment. Why did he experience this on the particular moment and day that he did? He can offer no explanation at all. It just happened.

I submit that when a meditator realizes the next state of consciousness, she knows exactly why—she is very much aware of everything that led up to it, and why it occurs when it does. In fact, as one travels the spiritual path, one learns to measure her awareness with great precision, so that in fact she always knows where she is in relationship to where she is going. There is a persistent belief—going back at least to Buddha, and fed by much of the Zen literature—that enlightenment occurs in a flash, that it may happen at any time, and that sometimes it even requires very little practice. Today, this is often expressed in the notion that enlightenment is an accident, and that the purpose of spiritual practice is just to make us more accident-prone.

I cannot encourage people strongly enough to reject this view. Enlightenment is not an accident; it's the consequence of a very long and very difficult intentional practice. There are to be sure chance elements in the process, particularly in the circumstances that lead us to seek higher consciousness in the first place. [15] But once one truly begins, there is no life that is less accidental, where less is left to the role of chance events. A scientist, an artist, a scholar, a businessman, anyone leading an ordinary life can begin that life with a particular aim, and end up doing something he never would have imagined. This is simply because all such lives are motivated by desire, and our desires, and our perceptions of how best to satisfy them, constantly change. A genuine meditator does not become diverted in this way, because he is struggling with desires, not following them. Acutely aware of the effect of everything he does or interacts with on his state of awareness, he plans his life very carefully. The vulnerability that we develop—in which we can be profoundly affected by events and circumstances that people in the ordinary state of consciousness are not even aware of—makes this care essential.

Evolution at all levels occurs according to certain laws and patterns, which can be learned and understood by persistent efforts. At our own level, we know that newborn children do not develop physical, emotional or mental maturity overnight, and that when it does arrive, it does not do so suddenly or capriciously. It takes a certain length of time, and while there is some individual variation, no one is spared many years, and many ups and downs. This is not to say that there can be no novelty or surprise in the process. Children frequently make sudden discoveries, such as the ability to perform some physical act, feel some emotion, or grasp a new concept. The same can occur on higher levels, and such discoveries surely account for most if not all of the sudden "enlightenment" experiences reported in the literature. But just as full maturity is not a sudden, all-or-nothing event—not there one moment, there the next—so enlightenment is much more accurately viewed as something we realize slowly and gradually.[ 16]

If You Want to Go to Heaven, Do it in Seven

While an understanding of the meditative process, and the experiences it furnishes, should be the central focus of any teacher, many of them also attempt to develop a larger context in which meditation takes place—in other words, a worldview. This is most common among contemporary teachers, living in our highly scientific world, but even much earlier mystics generally had some kind of map of existence, which provided a notion of where one was and where one was trying to go. Adi Da's worldview is summarized in his teaching of the seven stages of life, a series of levels of development. This worldview, clearly, is not original. It resembles in some respects Gurdjieff's seven types of men (which itself borrowed heavily from still earlier teachings), with the first three stages representing the physical, emotional and mental development that all normal humans pass through, and the higher four stages various levels of consciousness beyond that of ordinary humans. Da's system also offers a far less detailed account of the lower stages than Ken Wilber's model (Wilber 1980).

Nevertheless, Da's model might be expected to be of particular interest in light of his claims for intimate acquaintance with higher states of consciousness. If he, and he alone, has passed through all the stages beyond humanity, perhaps he can provide us with insights into them not available through other sources. Let's look at his descriptions, beginning with the fourth stage, the first one above the mental level which is ordinarily the highest that humans attain. According to Da, this fourth stage features

Yielding of the total body-mind-self to ecstatic (or self-transcendent) communion with the transcendental divine source-condition…true fourth stage practice goes beyond religious conventions (wherein the divine is considered to be outside and apart from the separate self)…The passage through and beyond the fourth stage of life depends on self-transcendence…[17]

That the next state of consciousness involves transcending our current one is only to be expected. What one might wonder, at this point, is if the fourth state involves transcendence (of the ordinary self), what do the higher states involve? Transcendence of still higher selves? Keeping this question in mind, let's move on to Da's description of the fifth state:

Spontaneously free of necessary identification with the gross body and its relations and conventional limitations of waking consciousness (including the verbal mind and the outer-directed actions of the left of verbally dominated hemisphere of the brain)…The fifth stage process tends toward the temporary and transitional realization of conditional or fifth stage nirvikalpi samadhi…[18]

Here there is a further description of the process of transcendence, but nothing that I can see to distinguish it from the transcendence of the fourth stage. Of course if one transcends the ordinary self, one no longer identifies with the "verbal mind". But why couldn't one say the same of the fourth stage? Moving to sixth stage, we are told, is

Awakening to the transcendental self…identification with the individual or separate conscious self, prior to or apart from body and mind…[19]

Yet again, the description reads, to me, much like the fourth and fifth stages. There is a transcendence, a going beyond identification with body and mind, but it is not obviously clear, from this passage, how this transcendence differs from that of the lower stages. Da does provide further descriptive details of these stages that I have not quoted here. For example, they are discussed in terms of the energy currents previously mentioned. As one progresses through these stages, these currents move progressively higher up the nervous system, and through the top of the head. I find such discussions inaccurate as well as unhelpful for any understanding of how these higher stages are related to the lower. Still further, he seems to equate the fifth stage with dreaming sleep, and the sixth with deep sleep. Almost all scientists and psychologists view the states of sleep as lower, not higher, than our ordinary waking consciousness, and given the abundant evidence that many lower organisms experience them, it's difficult to take Adi Da's position here seriously (see Smith 2001c for further discussion of this point).

One way of viewing Da's higher stages that seems to be consistent with his descriptions of them is that while stages 4-6 all involve transcendence, in all of them this transcendence is incomplete; the degree of completion increases with each stage, but only becomes total with the seventh and final stage. This interpretation is supported by several passages in which these earlier stages are described as having fleeting, temporary experiences of the divine. Indeed, Da takes great pains to emphasize this in his discussion. This view of these stages as a partial realization is also consistent with Da's claim that it is not really necessary to experience them, at least completely; it's possible to bypass these stages to some extent, and go more or less directly to the seventh.

However, if this is the case, then these stages don't sound like stages in the same sense that the first three are. It is certainly not possible to skip the physical or emotional stages on the way to the mental stage. So the relationship between the first three stages, on the one hand, and the last four, on the other, seems quite different, and whether each should in fact be called a stage in any meaningful sense is called into question.

There is also a problem with Da's treatment of the lower stages, taken by themselves, a problem also found in Wilber's model, as several critics besides myself have pointed out (Washburn 1998; Goddard 1999; Smith 2000a; O'Connor 2001). In Da's and Wilber's models, each stage or level is supposed to transcend the level below it, but the relationships of the lower human levels to each other are not like this. The emotional level does not transcend the physical, nor does the mental level transcend the emotional. In true transcendence, a higher holon does not simply contain lower ones, but integrates them, and as both Wilber's and Da's models make very explicit, the third or mental stage, as the culmination of ordinary human existence, does not in fact integrate the lower two stages. Both these writers emphasize that people in the ordinary state of consciousness are not fully integrated. This only comes later, with development into higher levels. As I have discussed at length elsewhere (Smith 2000a), the relationship of the physical, emotional and mental stages to one another is better described as transforming rather than transcending. There clearly is a level beyond our ordinary one in which transcendence does occur, but Da's model does not make it very clear, to me at least, whether this takes place at stage 4, or only at the culmination at stage 7.

In conclusion, I don't find Da's seven stages very helpful as a guide or map to higher realms. Obviously it's difficult to describe stages or levels above our own in verbal terms, since these stages are supposed to transcend the verbal body-mind. But at the least, these stages should be related to one another and to lower stages in a way consistent with what we know about the latter. In particular, every new level of existence should be associated with a new self—not just a more frequent or more permanent realization of the highest self—and some sense of the self's limits should be apparent. Da's descriptions of these stages do not convey this information to me.

One reason delineating the nature of these intermediate selves is so important is that it makes it possible to build a meaningful bridge between science and spirit—one of Ken Wilber's major stated aims. One of the commonest criticisms of this project is that spirit, as Absolute, is completely beyond content or form, and therefore seeking it can have nothing in common with science (Erdmann 2001). Regardless of whether this is a valid criticism or not, there is a very effective answer to it. The next level of consciousness, which is all any spiritual seeker on earth should really be concerned with, is not the Absolute. It transcends the body-mind, and is beyond all verbal descriptions, and is ineffable, and so on, and so on. But if it is not highest level, it is not the Absolute, and therefore seeking it can at least in principle be understood in terms of a method that has something in common with science. Recognition of this simple but often overlooked point could go a long way towards defusing much of the antagonism of many philosophers and scientists to a possible synthesis of religion and science.

"The Way that I Teach"

However one feels about the truth and the profundity of Da's writings, there is little argument that the way he put his ideas into practice, through his teachings, was flawed, at best ineffective for most people, at worst highly destructive of human lives. However, some appreciation of the context in which he began teaching is important. At that time, in the early 1970s, spiritual practice was considered by most people to be associated with a very straight-arrow, mill-to-the-grindstone, ascetic type of lifestyle. This attitude was not universal—Gurdjieff's teachings clearly pointed to another way, as did Castaneda's writings—but the Eastern traditions that most influenced Da emphasized the path to higher consciousness as withdrawal from the everyday world, not engagement with it. At this time, thousands of Westerners were retreating to Indian ashrams, where they were taught to discard their possessions and live simply.

Da's "crazy wisdom" approach challenged this, or at least had the potential to do so. Though as I said earlier, I never met him nor participated in any way in his community, my understanding is that he was attempting to show people how to detach from their desires not by avoiding their objects, but by confronting them. Da's approach in this respect strikes me as a little like that of Gurdjieff, whom I greatly respect as one of the most visionary thinkers as well as powerful teachers of all time. Like Gurdjieff, I think, Da recognized that the name of the game is detachment, and there are many methods and lifestyles besides asceticism that can promote this process.

To be successful, however, one must be master of not simply realization, but of living in the ordinary world. Gurdjieff displayed this mastery to a far, far greater degree than Da. He spent many years wandering through the Orient, at a time and in places where visiting temples of knowledge was not a simple matter of dropping in or accepting an invitation. Gurdjieff never depended on his followers to support him or his organization, but showed a genius as a businessman. He lived through the Russian Revolution and two world wars, moving through areas where even the boldest adventurers might have hesitated to go. And perhaps most important, Gurdjieff had a much more realistic understanding of his limits as a teacher, far broader than Da's limits though these were. He never proclaimed that he was for everyone. On the contrary, he often went of out of his way to discourage people from seeking him. Only someone with an enormous talent he intentionally doesn't use can understand how difficult this is.

Da, moreover, was not simply much less skilled than Gurdjieff at living in the world, but violated the first rule of teaching: live by example. Don't ask students to do what you won't do. While at least some of his students were pressured to give up wealth and material possessions, Da lived royally. While they were advised—in a long chapter in The Dawn Horse Testament—to live monogamously and to give up sexual orgasm for the most part[20], Da accumulated a harem. Regardless of whether or not one believes Da was completely beyond his body-mind, and that therefore he could live any kind of lifestyle without affecting his spiritual development, surely a teacher has an obligation to show his followers how their lives are to be led.

The hypocrisy involved has been the subject of much discussion and criticism of Da, and I don't intend to add to that here. I want instead to point to another potential flaw in Da's approach to teaching that has has been largely ignored. An important idea introduced by Gurdjieff—which is now widely appreciated in many other areas of life—is that teaching is not a one-way process; the teacher gives, but also gets. In Gurdjieff's system, this idea was presented in the metaphor of a stairway. As one develops, one climbs a series of steps, and in order to go up the next step or stage, the individual has to bring someone below his level up to her current step.

This idea is based, to at least some extent, on a still more fundamental principle in Gurdjieff's system: reciprocity. In Gurdjieff's view of the cosmos, every form of existence is engaged in a process of interacting with other forms; put most bluntly, everything must eat or consume in order to survive, but everything in its turn is also consumed. The teacher-student relationship is also a form of reciprocity; indeed, in Gurdjieff's view, knowledge is a kind of substance, like everything else, and so its transmission has to involve the simultaneous reception of some other substance. Thus it isn't just that the student is morally obligated in some way to give something to the teacher in return for the lesson. In the Gurdjieffian view, there is no choice. Nothing can be transmitted in a one-way manner; the act by which one person makes certain knowledge available to another person necessarily involves receiving something.[21]

Adi Da shows no sign of appreciating this kind of relationship, at least not in the books of his that I have read. In his view, very apparently, the teacher knows not simply more than the student, but everything there is to know. He is beyond learning anything. Therefore, teaching cannot be a two-way process, but is simply a means by which he encourages others to realize what he has realized. Again, even if we were to give Da the benefit of the doubt, and assume he has attained the ultimate level of realization, surely there should be room in his philosophy for a more dynamic teacher-student relationship with lesser-realized teachers.

Conclusion

Descriptions of this kind are very clearly those of someone who has withdrawn from everyday life.

Though I have been quite critical of Adi Da's philosophy here, I don't want to leave the reader with the impression that I have no respect for it. He clearly is highly intelligent, widely read, and most important, intensely motivated to search for the truth. A great deal of this truth shines forth in his writings, not just in what he says, but in the way he says it. He has been astonishingly productive, and when you add to this his (mostly former) ability to gather around himself and motivate other people, I don't think it's excessive to call him brilliant. I wouldn't even debate too strenuously Ken Wilber's assertion that The Dawn Horse Testament is comparable in many respects to some of the great spiritual classics of the past. I believe the power of Da'swritings is based far more on his ability to express ideas he picked up from others than on his unique personal experience,but such retelling is certainly a valid element in a spiritual classic.

This assessment, however, says more about my judgment of these earlier treatises than of Da. Like Da, these classics are very good at singing the praises of a higher state of being that transcends our own, of filling our eyes and ears with its splendors, and with reasons why we should want to realize it. But like Da, relatively few of these classics can say very much about what people actually experience in the process of going from "there" to "here". Again and again they fall back on visions, on voices, on bodily pains and contortions, and on energy currents that traverse anatomical paths unknown to science. Descriptions of this kind are very clearly those of someone who has withdrawn from everyday life, and become rather obsessed with the goings-on of an inner world. As Laurence LeShan pointed out a quarter of a century ago in what I still regard as one of the wiser books on (beginning) meditation, when the human mind is forced to endure a period of boredom, it often becomes very creative at entertaining itself (LeShan 1974).

Lost to so many of these early pioneers, and I think to Da, is that the same process that goes on while on the mat must continue, in exactly the same way, when we carry on with the rest of our lives. The benefits and effects of sitting meditation, whether performed for the twenty minutes a day favored by the Maharishi Institute or the two and half hours a day advised by Da, do not somehow magically "carry over" to the rest of our lives, unless we continue to meditate at these times. If we do, some of the richest imaginable experiences open up to us, experiences that extend our knowledge of the ordinary world and the body-mind as well as what lies beyond them. These experiences, surely, are the key to developing universal principles of meditation, and creating meaningful maps to the higher realms, maps guided by the essence of the scientific method even as they lead us to areas that science itself can't penetrate.

Footnotes

- The Case of Adi Da (1996). This is available at the Shambhala website, www.shambhala.org

- The Knee of Listening, p. 243.

- The Dawn Horse Testament, p. 87. In this text, words that ordinarily would not be capitalized often are. In all the quotes presented here, I have followed the usual rules for capitalization, rather than Da's.

- Quoted at the Daism Research Index site: http://lightmind.com/Impermanence/Library/knee/frank-01.html

- I think, for example, of Capra (1976) claiming he could see the dance of subatomic particles, or Pert (1997) claiming she could observe molecules in her body. Actually, even if humans could have direct experience of molecules or cells, they probably would not appear the way they are scientifically described. Our scientific descriptions of lower forms of life constitute the way they appear to our human consciousness, or would appear if we could see holons this small. But when we experience a holon on its own level, we do not and cannot use our ordinary human consciousness. We must perceive it in the same way that other holons on this level perceive themselves.

- We can also communicate with lower holons within our body, such as individual organs Through certain forms of yoga and other practices, it may be possible through practice to develop a high degree of intimacy with these organs. I do not believe, however, that it is possible to become intimate with individual cells within our bodies in this way. I have seen no convincing evidence that a yoga adept can affect the function of a single cell in his body.

- The evidence for this, briefly, comes from the nature of the emergent properties holons can take on as they become part of higher-order holons. An atom that is part of a molecule may have properties not found in atoms that are not part of molecules, because the former type of atom can participate in the emergent properties of the molecule. As molecules become increasingly more complex, the emergent properties of their component atoms can likewise increase. The limit to this emergence, however, is at the cell. Atoms in cells can have their most complex properties. It no longer matters whether the cells themselves become part of still higher forms of life; the component atoms of these cells are no more complex or emergent than atoms found in cells that exist autonomously.

From this evidence, we can conclude that the cell is the highest form of life that an atom can in any way participate in, and presumably have any awareness of. Any higher form of life has no effect on its properties or its functions, and therefore it should not have any awareness of it. The same argument can be made with respect to a cell and an organism; an organism is the highest form of life that a cell can participate in. In each case, a full level above the holon in question sets the limit.

The reader might wonder why, if cells can develop in this way up to the level of the organism, humans could not maintain a connection with individual cells. The answer is that (in my model of holarchy) humans do not actually exist at the level of simple organisms. Because humans are members of societies, and in fact participate in the emergent properties of those societies (just as atoms participate in the properties of molecules, and cells in the properties of tissues and organs), they are situated more than a full level above the existence of cells. A cell might be able to identify with a very simple, asocial organism.

- Some people might claim that as awareness of higher states of existence increases, so does awareness of lower states. That expanding consciousness carries with it the power to go in both directions of the holarchy. In the limit, there is awareness of everything. The problem with this point of view is that it implies there should be no holons with any limits to awareness. If the highest form of consciousness can maintain complete contact with any and every individual, for example, why are not all humans enlightened? Are two separate consciousnesses inhabiting every bodymind?

- "On the Nature of a Postmetaphysical Spirituality. Response to Habermas and Weis" Interview with Ken Wilber. wilber.shambhala.com

- For a discussion of the relationship of these two types of perception in the context of holarchy, see Goddard (2000); Smith (2001a,b).

- Dawn Horse Testament, pp. 279-280

- The Method of the Siddhas, p. 110.

- There may be a few exceptions to this. Not all thoughts are the result of some desire (see Smith 2000b).

- Dawn Horse Testament, pp. 179-180.

- How ironic that this is the one aspect of the spiritual process that so many New Agers believe is not the result of chance. There is a very widespread myth, apparently deriving from Carl Jung's notion of synchronicity, that one is led to the spiritual path through a series of apparent coincidences. As far as I can tell, proponents of this view are confusing the notion that everything is connected and therefore ultimately related to everything else with the very different idea that two particular events have a special meaning exclusive of other events.

- This is not to say that complete awakening is not a profound event. Da described his enlightenment as a rather ordinary discovery, not really a big deal. In one sense, I would agree. No bells or horns or flashing lights. By the time one reaches this point, one has endured so much for so long that one is well prepared for it. It's shock value has been to some extent discounted. On the other hand, a boundary is crossed. The next state of consciousness (whatever that corresponds to in Da's scheme; see the following section) brings with it freedom from physical death. No matter how how much one develops before this point, one is still mortal. So realization of this state is profound. If the path up to this point is a form of gradually dying, realization of the next state is actual death.

- Dawn Horse Testament, pp. 202-3.

- Dawn Horse Testament, p. 204.

- Dawn Horse Testament, pp. 206-7.

- The notion that sexual orgasm, particularly by men, wastes or eliminates bodily energies, is another idea Da has borrowed more or less wholesale from others. I really don't understand it; it strikes me as the kind of conclusion that could be drawn only by someone with a poor understanding of the relationship of awareness and energy. Does sexual orgasm involve using energy that could otherwise go to increasing awareness? Yes, but so does every human activity. Ejaculation uses less energy, for example, than walking three or four steps, or talking for 10-15 minutes (or, for that matter, extended foreplay). As for eliminating vital body fluids, this is a perfectly natural and healthy process. Evolution has selected for mammalian males that can and usually do frequently copulate, and if they don't, the fluids they build up are likely to cause health problems. While I wouldn't discourage someone from experimenting with techniques for preventing orgasm discussed in The Dawn Horse Testament, this experimentation should be done with great care, and no one should do so because he believes abstinence is necessary to spiritual development.

- The two-way relationship between teacher and taught could be rationalized in an additional way. If we observe the development of consciousness up to our own current level of humanity, it's clear that it has a very close relationship with social organization. That is, the particular characteristics of modern men and women that distinguish them from people of the past—their intellectual, emotional, moral, etc. development—clearly depend on being members of very large and complex social organizations. It seems, therefore, that new levels of consciousness cannot emerge and be realized by human beings apart from a parallel emergence of new forms of social organization. Application of this idea to higher levels, beyond our own, implies that a certain number of people have to advance to a certain stage before a consciousness capable of being realized by anyone is possible.

References

Berne, E. (1996) Games People Play (New York: Ballantine)

Capra, F. (1976) The Tao of Physics (Boulder, CO: Shambhala)

Da, A. (1985) The Dawn Horse Testament (San Rafael, CA: Dawn Horse Press)

Da, A. (1992a) The Knee of Listening (San Rafael, CA: Dawn Horse Press)

Da, A. (1992b) The Method of the Siddhas (San Rafael, CA: Dawn Horse Press)

Erdmann, M. (2001) "Brahman Reduced to Sensory Science" http://groups.yahoo.com/group/Integral-ION/

Furlong, M. (1996) Visions and Longings (Boston: Shambhala)

Goddard, G. (1999) "Airing our Transpersonal Differences" www.integralworld.net/goddaard.html

Goddard, G. (2000) "Holonic Logic and the Dialectics of Consciousness" www.integralworld.net/goddard2.html

LeShan, L. (1974) How to Meditate (Boston: Little Brown)

Minsky, M. (1985) The Society of Mind (New York: Simon and Schuster)

O'Brien, E. (1964) Varieties of Mystic Experience (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston)

Ouspensky, P.D. (1961) In Search of the Miraculous (New York: Harcourt, Brace Jovanovich)

Peers, E. A., ed. (1989) Interior Castle (New York: Image)

Pert, C. (1997) Molecules of Emotion (New York: Touchstone)

Ramachandran, V.S. (1998) Phantoms in the Brain (New York: William Morrow)

Smith, A.P. (2000a) Worlds within Worlds, www.geocities.com/andybalik/introduction.html

Smith, A.P. (2000b) Illusions of Reality (www.geocities.com/andybalik/tmm.html

Smith, A.P. (2001a) "Quadrants Translated, Quadrants Transcended" www.geocities.com/andybalik/QT.html

Smith, A.P. (2001b) "Who's Conscious?", www.geocities.com/andybalik/wc.html

Smith, A.P. (2001c) "Footprints in the Sand" (www.geocities.com/andybalik/footprints.html)

Underhill, E. (1961) Mysticism (New York: Dutton)

Washburn, M. (1998) "The Pre/Trans Fallacy Reconsidered", www.thineownself.com/washburn.html

Wilber, K. (1980) The Atman Project (Wheaton, IL: Quest)

Wilber, K. (1995) Sex, Ecology, Spirituality (Boston: Shambhala)

Wilber, K. (1998) "A More Integral Approach" in Ken Wilber in Dialogue (Rothberg, D. and Kelly, S., eds.) Wheaton, IL: Quest, pp. 306-367

Wilber, K. (2000) Integral Psychology (Boston: Shambhala)

|

Andrew P. Smith, who has a background in molecular biology, neuroscience and pharmacology, is author of e-books Worlds within Worlds and the novel Noosphere II, which are both available online. He has recently self-published "The Dimensions of Experience: A Natural History of Consciousness" (Xlibris, 2008).

Andrew P. Smith, who has a background in molecular biology, neuroscience and pharmacology, is author of e-books Worlds within Worlds and the novel Noosphere II, which are both available online. He has recently self-published "The Dimensions of Experience: A Natural History of Consciousness" (Xlibris, 2008).