|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Don Salmon, a clinical psychologist and composer, received a grant from the Infinity Foundation to write a comprehensive study of yoga psychology based on the synthesis of the yoga tradition presented by 20th century Indian philosopher-sage Aurobindo Ghose. Jan Maslow, an educator and organizational consultant, has, with Dr. Salmon, given presentations, classes and workshops in the United States and India on this topic. Both have been studying yoga psychology for more than 25 years. Don Salmon, a clinical psychologist and composer, received a grant from the Infinity Foundation to write a comprehensive study of yoga psychology based on the synthesis of the yoga tradition presented by 20th century Indian philosopher-sage Aurobindo Ghose. Jan Maslow, an educator and organizational consultant, has, with Dr. Salmon, given presentations, classes and workshops in the United States and India on this topic. Both have been studying yoga psychology for more than 25 years. The Conflict Between Soul and Ego in the Life of AmericaDon SalmonMy concern is not whether God is on our side; my greatest concern is to be on God's side. Over the past 6 months or so, I've been presenting excerpts from a book by Jan (my wife) and me which explores Sri Aurobindo's Integral Psychology: "Yoga Psychology and the Transformation of Consciousness: Seeing Through the Eyes of Infinity." The excerpts have all been related to the evolution of consciousness. I decided this summer, with all the talk of Lincoln, I would offer an excerpt on a different topic. Hope you enjoy it! The Hidden Spiritual Tradition in AmericaEugene Taylor, historian of psychology and psychiatry at Harvard University, in his book "Shadow Culture," describes a tradition of folk psychology, "an inwardly oriented psychology of spiritual consciousness that has been an integral part of American culture from its very inception."[2] This "folk tradition" has been concerned with the exploration of "different states of interior consciousness," and is "spiritual insofar as its function is the evolution and transformation of personality."[3] Although for much of American history this folk psychology has been spurned by the mainstream culture, in the last half century it has emerged "out of the shadow"[4] into the light, as evidenced by increasingly widespread interest in meditation and other ways of transforming consciousness. Taylor proposes that this tradition of folk psychology represents a fundamental spiritual impulse native to the American Soul. He describes the tradition as fundamentally optimistic, eclectic and pragmatic in nature, involving a "blending of science and religion, spirit and matter, mind and body."[5] And it is an impulse that reverberates throughout the American character—expressing itself as a seeking for freedom from outer authority, the freedom to pursue individual inner experience and to express it within one's community. The yearning for freedom of religious expression and experience was a driving force in the American culture since the founding of the colonies. Religious scholars identify two periods in American history, known as the Great Awakenings, when this yearning became particularly intense. During these times, large numbers of people became involved in a search for immediate inner or spiritual experience, in the process experimenting with new forms of religious ritual. This experimentation took place within the dominant Christian culture. Taylor identifies two subsequent periods of intense spiritual seeking, in which an Asian influence became more prominent.

Empire vs. Democracy—Egoic Self-Aggrandizement vs. Spiritual Self-Determination[8]It is striking—and no coincidence—that America now faces the prospect of military action in many of the same lands where generations of colonial British soldiers went on campaigns... where, by the 19th century, ancient imperial authority... was crumbling, and Western armies had to quell the resulting disorder... Afghanistan and other troubled lands today cry out for the sort of enlightened foreign administration once provided by self-confident Englishmen in jodhpurs and pith helmets. Arrogant, full of self-esteem and the drunkenness of their pride, these misguided souls delude themselves, persist in false and obstinate aims and pursue the fixed impure resolution of their longings. They imagine that desire and enjoyment are... the aim of life...[and] are the prey of a devouring, a measurelessly unceasing... anxiety till the moment of their death. Bound by a hundred bonds, devoured by wrath and lust, unweariedly occupied in amassing unjust gains... they think, "To-day I have gained this object of desire, tomorrow I shall have that other; today I have so much wealth, more I will get tomorrow. I have killed this my enemy, the rest too I will kill. I am a lord and king of men, I am perfect, accomplished, strong, happy, fortunate, a privileged enjoyer of the world; I am wealthy, I am of high birth; who is there like unto me? I will sacrifice, I will give[alms], I will enjoy." Taylor's view of the underlying spiritual significance of the Great Awakenings is not the common one. Religious studies scholar Karen Armstrong, presenting the more prevalent view, sees them as times of "frenzied religiosity."[11] According to Armstrong, it was a period of great societal change, which led many colonists to seek solace in intense religious experience, sometimes taking the form of "born-again conversions."[12] People in revival meetings "fainted, wept, and shrieked; the churches shook with the cries of those who imagined themselves saved and the groans of the unfortunate who were convinced they were damned."[13] Commenting on the dangers of experimentation with such altered states of consciousness, she writes, "Once faith was conceived as irrational, and the inbuilt constraints of the best conservative spirituality were jettisoned, people could fall prey to all manner of delusions."[14] There seems to be quite a disparity between Armstrong's picture of "frenzied religiosity," and Taylor's image of "joyful exuberance and spiritual happiness."

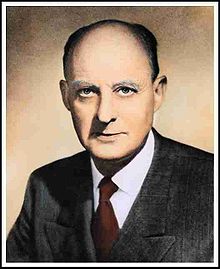

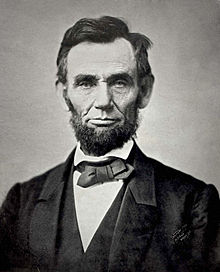

There seems to be quite a disparity between Armstrong's picture of "frenzied religiosity," and Taylor's image of "joyful exuberance and spiritual happiness." Armstrong does suggest, however, that the experience of the First Great Awakening helped pave the way for greater participation in the coming battle for American independence. "The ecstatic experience left any American who would be quite unable to relate to the[highly intellectual]... ideals of the revolutionary leaders, with the memory of a blissful state of freedom. The word 'liberty' was used a great deal to describe the joy of conversion, and a liberation from the pain and sorrow of normal life."[15] From the perspective of yoga psychology, it makes sense that the deeper spiritual impulse Taylor describes would have easily been diverted by the desires and needs of the surface vital consciousness, and significantly distorted by the undisciplined physical and vital mind. As Armstrong noted, "all manner of delusions" may result when an individual opens himself to the intense energies of the inner realm without sufficient preparation. In fact, Taylor is quite aware that the "shadow culture" of "folk psychology" has been a complex mixture made up of many different qualities and grades of consciousness. The yoga tradition has taught for thousands of years that it is crucial to develop a rigorous and astute sense of discernment if one is to navigate safely the domains of consciousness beyond the ordinary waking state.  Reinhold Niebuhr One of the greatest impediments to the development of a calm, clear discernment is the uncritical belief in one's own purity and innocence. As the great theologian, Reinhold Niebuhr writes, "nations, as individuals, who are completely innocent in their own esteem are insufferable in their human contacts."[16] Niebuhr was someone who recognized both the deeper spiritual impulse in American culture as well as the delusions and temptations to which the human being may easily fall prey. Wishing to bring attention to the delusions so that they not subvert the spiritual impulse, he wrote in 1952, "From the earliest days of its history to the present moment, there is a deep layer of messianic consciousness in the mind of America...[coupled with a widespread] inability to comprehend the depth of evil to which individuals and communities may sink, particularly when they try to play the role of God to history."[17] Rather than "claiming God too simply as the sanctifier of whatever we most fervently desire," Niebuhr appeals to us to hold "a sense of modesty about the virtue, wisdom and power available to us...[and] a sense of contrition about the common human frailties and foibles which lie at the foundation of both the enemy's demonry and our vanities."[18] To the extent this discerning awareness has been wanting over the course of American history, the culture (i.e., the collective personality of the nation) has accumulated a very heavy karmic debt. While the spiritual impulse is always mixed to some extent with ego and desire, the tendency for it to be co-opted by the forces of self-interest is especially great during wartime. Looking back on the comments of American leaders during various wars, it is not always so easy to discern where and in what way the deeper impulse has been distorted. For example, in 1917, President Woodrow Wilson, exhorting the American public to enter the fray of World War I, said in an address to the nation, "The world must be made safe for democracy."[19] On its face, this statement alone could be either an expression of American imperialism, or a genuine desire to spread freedom. Wilson continues, "Its peace must be planted upon the tested foundation of political liberty. We have no selfish ends to serve. We desire no conquest, no dominion... We are but one of the champions of the rights of mankind. We shall be satisfied when those rights have been made as secure as the faith and the freedom of nations can make them."[20] As noble and selfless as these declarations appear to be, it is hard to know whether they are as innocent as they sound. There are other wartime proclamations in which it is more apparent that spiritual claims may in part have been a guise for egoistic pride and self-interest. During the Civil War, the Reverend George S. Phillips spoke to Union troops, exhorting them to see themselves as fulfilling a greater mission, one which would "only be accomplished when the last despot should be dethroned, the last chain of oppression broken, the dignity and equality of redeemed humanity everywhere acknowledged, republican government everywhere established, and the American flag should wave over every land and encircle the world with its majestic folds."[21] Even here, one might excuse the reverend's excessively messianic language as an unusually intense but genuine passion for the liberty of all mankind. It seems more likely, however, that his vision of the American flag encircling the globe reflected, at least in part, a desire for American domination and control. An absence of innocence and humility in the following words is unmistakable. They are the words of Senator Albert J. Beveridge in an 1898 speech to the Union League Club, in which he objected to suggestions for bringing home American troops from the Philippines. Beveridge proclaimed that a retreat would be a betrayal of a trust as sacred as humanity... And so, thank God the Republic never retreats... American manhood today contains the master administrators of the world, and they go forth for the healing of the nations. They go forth in the cause of civilization. They go forth for the betterment of man. They go forth, and the word on their lips is Christ and his peace, not conquest and its pillage. They go forth to prepare the peoples, through decades and maybe centuries of patient effort, for the great gift of American institutions.[22] If any doubt remains as to the intention behind Beveridge's piety, consider his response to the assertion that the American involvement in the Philippines was an imperialist venture which violated the spirit of the Declaration of Independence: "[The Declaration of Independence] applies only to people capable of self-government...[not to] the Malay children of barbarism." And he further argues that the invasion had its roots in something "deeper even than any question of constitutional power...[God Himself] has marked the American people as His chosen nation to finally lead in the regeneration of the world."[23] Underlying the birth of the American experiment, there was a profound spiritual impulse, however much it may or may not have been conscious in the minds of the Founding Fathers. At the same time, due to the nature of the human psyche at this stage of evolution, there were also tendencies toward self-interest, greed and power-seeking of all kinds. To the extent America as a nation has repeatedly acted on each of these impulses (spiritual and egoic), the momentum engendered by both types of action has intensified, bringing us to a point of karmic reckoning. On the one hand, the deeper spiritual impulse has grown—not only in America but throughout the world, such that we now have the possibility of a global spiritual awakening. On the other hand, if we continue to be lost in the karmic momentum of ego and self-interest, adamantly asserting innocence of any wrongdoing, we may perish. In his work, "The Irony of American History," Reinhold Niebuhr writes: If we should perish, the ruthlessness of the foe would be only the secondary cause of the disaster. The primary cause would be that the strength of a giant nation was directed by eyes too blind to see all the hazards of the struggle; and the blindness would be induced not by some accident of nature or history but by hatred and vainglory. Abraham Lincoln—Navigating the Conflict Between the Soul's Aspiration and the Desires of the Ego Abraham Lincoln Perhaps few individuals in American history have risen to the challenge of spiritual discernment to the degree exemplified by Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States. Niebuhr, expressing his belief in Lincoln's capacity for genuine humility and discernment, wrote the following commentary on his second inaugural address, "The combination of moral resoluteness about the immediate issues, with a religious awareness of another dimension of meaning and judgment, must be regarded as almost a perfect model of the difficult but not impossible task of remaining loyal and responsible toward the moral treasures of a free society on the one hand, while yet having some religious vantage point over the struggle."[25] At the point he delivered his second inaugural address, Lincoln was feeling the weight of his responsibility to win the civil war and bring the country back from the brink of dissolution. In spite of this, he chose to challenge the claim of religious righteousness that would have conferred upon him authority to accomplish the task as well as the greatest justification for his resolve. And he dared others to do the same: Neither party expected for the war the magnitude or the duration which it has already attained... Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding. Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God's assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men's faces, but let us judge not, that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered. That of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes.[26] Lincoln commenting afterward on how his address had been received, said: I believe it is not immediately popular. Men are not flattered by being shown that there has been a difference of purpose between the Almighty and them. To deny it, however, in this case, is to deny that there is a God governing the world. It is a truth which I thought needed to be told; and as whatever of humiliation there is in it, falls most directly on myself, I thought others might afford for me to tell it.[27] Acknowledging his imperfection as an instrument of the God he aspired to serve, and exercising a rare discernment between the true and distorted spiritual impulse of the nation, Lincoln concluded his inaugural address with these words: With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation's wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.[28] NOTES

|