|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Keith Martin-Smith worked for Integral Institute from July 2006 until August 2007, when he left to pursue his own work. His collection of 12 short stories the Mysterious Divination of Tea Leaves, and Other Tales, a collection of “Integral” fiction, has been published by O-Books and is available through Amazon. Keith currently lives in Boulder, Colorado, where he teaches Kung Fu and Qi Gong, and works as a freelance writer. You can learn more about him and his work at www.keithmartinsmith.com. See also "Art, Postmodern Criticism, and the Emerging Integral Movement". Keith Martin-Smith worked for Integral Institute from July 2006 until August 2007, when he left to pursue his own work. His collection of 12 short stories the Mysterious Divination of Tea Leaves, and Other Tales, a collection of “Integral” fiction, has been published by O-Books and is available through Amazon. Keith currently lives in Boulder, Colorado, where he teaches Kung Fu and Qi Gong, and works as a freelance writer. You can learn more about him and his work at www.keithmartinsmith.com. See also "Art, Postmodern Criticism, and the Emerging Integral Movement".

On the Future of Art

|

|

|

| "Fountain", Duchamp | "Piss Christ", Serrano |

The Big One Turns into the Big Three

Fountain and Piss Christ have roots that go back many hundreds of years. To make this task less daunting, let's start with Gothic art in pre-Renaissance Western Europe, and take a quick tour through the territory that brought us into the 20th Century, where works such as Fountain and Andy Warhol's Campbell soup labels have become accepted as “legitimate” art. (Let me note that for reasons of length many complex ideas in this essay had to be greatly simplified. Art history, for instance, has been reduced to 3 major periods, whereas it is far more accurate that there have been dozens of “major periods” of art, which can only be very roughly collapsed into 3. A book about this topic will have the space necessary to make some important distinctions not appropriate to this essay. )

Like just about everything else, art evolves and changes through time, building upon the success, insights, mistakes, and innovations of what came before. In pre-Renaissance Western Europe, there was a single church based out of Rome, which everything served. Educated people were educated by the Church for the Church, and the first Western university, in Bologna, was founded in the 14th Century to serve the Church, not to challenge it.[3] “Science” basically consisted of re-proving Aristotle's ideas and integrating them into Church doctrine. “Philosophy” as we know it today did not exist — theologians of various kinds all worked to integrate ancient knowledge with biblical truths, but those biblical “truths” were not questioned. Another way of saying this is that intellectuals and artists of the day were largely fused with the ideas of the Church and Bible — there was no reflection on whether or not the Bible was true, there was only reflection on how to integrate both ancient knowledge and new knowledge with the absolute certainty of biblical truth.

You could say that today there are three grand areas of study: Art, Morality, and Science — the Big Three, according to the American philosopher Ken Wilber. These three now-separated areas of human study were actually fused into a single Truth for much of the early to late Middle Ages — at least until the Renaissance began to pry them into separate spheres of understanding and study. I will come back to this to explain it more fully in a moment.

Art

Art, as anyone who has visited a pre-Renaissance wing of any museum has seen first-hand, was done exclusively to glorify God, the saints, and biblical truths. The art is often unsigned, and there is no deviation from the theme of God, saints, and Bible until the 15th Century. Art was not an expression of an artist's experience, or their version of 'truth', or their subjective take on Church “truth”. Art was simply fused with the absolute certainty of biblical truth as expressed by the Holy Roman Catholic Church. Art was done to glorify God, and for no other purpose.

Science

Scientific truths also had to reflect the mythological Christian understanding of the world. Physical ailments, for example, were considered caused by spiritual deficiencies, and so Western “medicine” progressed little if at all for over a thousand years. The body, as presented by the Bible, was considered a hindrance to the liberation of the spirit. One needed to deny bodily impulses like lust if one was to get to heaven, and the earth itself was considered a corruption compared to the bliss and perfection of heaven. This fusion of science and mythic religion can be best seen, perhaps, when Galileo told the Inquisitors that all they needed to do was look through his telescope to see for themselves that moons orbited Jupiter — demonstrable proof that the Earth could not be the center of the universe — and the Inquisitors famously replied something along the lines of, “We do not need to look, for we already know what is there.” They “knew” because the “truth” of the Roman Catholic dogma was absolute for them, and any “fact” that contradicted Church teaching had to be wrong. We see same sort of circular reasoning today with Fundamentalists who maintain the earth is 6,000 years old because the Bible says it is. They must dismiss or explain away any facts that contradict their mythological understanding of the world — facts must serve mythology, and no fact will ever, ever change their mind. So in pre-Renaissance Europe, science and art were either derived from or forced to conform to religious truth.

Morality

Morality also existed only as it applied to the Bible. All moral and ethical truths were traced back to the Bible for justification, and as a result things like slavery, capital punishment, vicious corporal punishment, torture, and rape had a solid moral foundation. Executions for trivial offenses were common (for as little as stealing and adultery was based on Exodus 21:16). The murder of “witches” was inspired by Exodus 22.18, “Thou shall not suffer a witch to live.” The morality of a law was simple: if it could be traced to the Bible, it was “moral” and “just”.

It is very, very important to note that in pre-Renaissance Europe there was not a grand conspiracy in which the Church suppressed thought and brain-washed people into believing a certain way — active suppression of scientists like Galileo and philosophers like Bruno did not occur until the Renaissance was well underway centuries after gothic art had faded into the hyper-realistic artwork and the larger-than-life artists who made it. Suppression only began when people and cultures began to drift (differentiate) away from a fusion with the Roman Catholic's version of “truth”, which began softly in the 14th Century before turning into a roar 100 years later.

Art as a Movement of Differentiation

A truism: Art reflects the culture and the worldview of the person who makes it. 14th Century Gothic art in the West, showing two-dimensional saints and other religious figures with elongated faces and bodies, were meant to portray certain religious truths symbolically. 14th Century Europe only had a worldview capable of seeing that kind of art — something like Duchamp's Fountain or Picasso's Guernica would make absolutely no sense and, far from being condemned, would have simply been ignored. To be understood, those works demanded a level of differentiation that simply was not present in 14th Century Europe. The reason is the Big 3 (art, science, morality) were, as we have seen, still fused into a single idea — science and art and morality all served God, and God was, in essence, the Church.

Western Europe, after nearly 700 years of the “dark ages” following the fall of the Roman Empire, began to organize itself in the12th Century. By the 15th Century, more and more thinkers were beginning to question the assumptions of the Church, and to differentiate art, science, and morality. In the realm of art, in the early 15th Century Leon Battista Alberti and Filippo Brunelleschi, “invented” perspective in painting, changing art forever. Suddenly the viewer was at the center of the work, and within 100 years of this Martin Luther, John Calvin, and Henry VIII were all using newly differentiated ideas of nation and religion and morality to radically challenge the Church. Christian Humanism, starting with Petrarch in the 1300's, quickly became the dominant philosophy driving the differentiation of art and science away from religion and morality.

This culminated with the great discovers and insights of the Renaissance, which supplanted the mythically-bound logic and science of the High Middle Ages with the beginnings of a true revolution in human thought:

Within the span of a single generation, Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael produced their masterworks, Columbus discovered the New World, Luther rebelled against the Catholic Church and began the Reformation, and Copernicus hypothesized a heliocentric universe and commenced the Scientific Revolution….Man was now capable of penetrating and reflecting nature's secrets, in art as well as science, with unparalleled mathematical sophistication, empirical precision, and numinous aesthetic power….He could defy traditional authorities and assert a truth based on his own judgment… Polyphonic music, tragedy and comedy, poetry, painting, architecture, and sculpture all achieved new levels of complexity and beauty.[4] [italics are mine, for emphasis]

Science, art, and morality were becoming less and less fused with a biblical truth, and more and more differentiated from one another. Science began to ask questions about Truth, art questions about Beauty, and morality questions about Good — but all of these questions were asked while essentially ignoring the truth claims of the Bible. Learning about the True, the Beautiful, and the Good outside of religious dogma became the ultimate intellectual human pursuit.

Painting continued to be the defacto visual record of human events, but after the 15th Century was marked by an attempt to get closer and closer to Truth — Realism — to capture reality “as it really was” independent of a Biblical god. And likewise in philosophy, religious truths continued to fall to scientific and rational ones, through Newton and Darwin in the sciences, and Descartes, Voltaire and Kant in philosophy. But everyone was pursuing the truth, not a better version of it. Newtonian philosophers didn't believe they had a better “version” of the truth than the Church, they too believed they had “the” Truth (emphasis on the capital “T”), and often viscously attacked religion and its proponents. In art, science, and morality, the “Truth” was being sought “out there” in the world, where it could be “proven” to be absolutely true. (It would take postmodernism to show the futility and impossibility of any quest for a singular truth, and Integralism to make sense of the whole picture, which we'll get to shortly.)

Realism in Art

Figure 1.0 Realism

Aesthetic Beauty is…

- Absolute and fixed

- Real, & outside the artist

- Independent of culture

- Independent of human view

From the Renaissance onward, the arts had been consumed with Realism, which assumed an absolute and fixed aesthetic value independent of the artist. Artistic works were judged harshly against this fixed standard, so that many works now considered “classics” were either openly ridiculed or utterly ignored. [Melville's Moby Dick, as but a single example, sold less than 3,000 copies and was almost universally misunderstood before sliding into obscurity until rediscovered in the 1920's.]

Realism continued in various forms right through the early 20th Century, and is still with us today in many forms. At its height, though, it included not only visual arts but also music, literature, sculpture, architecture, and dance. Realism matured with the invention of the novel (by Flaubert), and mastery of Realism in literature was achieved with Joyce (with Dubliners), Crane, and other writers. Of course, there were many subgroups under the banner of Realism from satirists (like Pope and Swift) to Romantics (like Wordsworth and Coleridge), but all still belonged under the broader banner of Realism. They were all trying to capture the world “as it really was”. For instance, the Romantics believed Truth was emotional while the Rationalists believed is was logical, but the underlying assumption of figure 1.0 was the same for both camps.

Modernism in Art

Figure 1.1 Modernism

Aesthetic Beauty is…

- Absolute but subjective

- Real, & inside the artist

- Dependant on culture

- Shaped by human view

It is no coincidence that Realism in art went into its death throes right around the time photography became well known in the mid-19th Century. Photography did what art never was able to do — it actually did capture things “as they really were”, removing any subjectivity the artist might put into their work. There really was an “objective” world a photograph could capture free of any interpretation. And then an interesting thing happened — within 50 years art became all about subjectivity in almost every domain in which art could be expressed, from music to architecture. Think about that: within 50 years of the widespread use of photography, art gave up any pretense of being “objective” at all, and instead threw itself into the power of the subjective experience. Realism continued on (and is still used today), but it was no longer the avante garde, cutting-edge expression.

While photography officially killed Realism, its end had begun much earlier, in philosophy. With Realism (as with much of the philosophies that supported it), people assumed a reality “out there” that humans “discovered” through reason, science, intuition, and logic. But beginning powerfully with the philosopher Immanuel Kant, this idea of a reality “out there” began to fall apart. Kant said:

…the order man perceives in his world is an order grounded not in that world but in his own mind: the mind… forces the world to obey it's own organization. Man can obtain certain knowledge of the world not because he has the power to penetrate and grasp the world in itself, but because the world he perceives and understands is a world already saturated with the principles of his own mental organization.[5] [italics are mine]

In other words, it was assumed before Kant that there was an exterior world we, as humans, could “report” on. What we saw and thought reflected a world “out there” “as it really was”. Rationalists like Descartes and Leibniz assumed that mathematics and the rational foundations of science were eternal and fixed — they were, somehow, “out there” waiting for human discovery.

Kant turned that idea on its head, and showed that we can never prove a world outside of human perception and interpretation. We can, he said, only see what our senses and intellects allow, which might be far different than the way things “really are”. All humans, after all, are subject to the same prejudices of biology and conditioning, in the broad sense of those words. Maybe Ralph Waldo Emerson summed up this position best, “What we are, only that can we see.”

Another way to phrase Kant's observation is that humans once again differentiated — this time, from the idea that there was a fixed Truth “out there” waiting to be discovered. First it was assumed that the Bible was true and “out there”; then it was assumed that Rationality and Objectivity were “out there”. Kant showed that both positions were impossibly naïve.

Art soon began to explore this very idea of subjectivity in intuitive mediums in Modernism, which unfolded as Nietzsche talked about the death of god and the brutality of religion, Marx questioned the very foundations of Western culture, Freud discussed our hidden agendas, Einstein described how space and time were non-absolute, and more and more artists and philosophers came to see the shadow side of the Industrial Revolution — child labor, working conditions that seemed to turn free men into near-slaves, appalling environmental ruin, the stratification of society. Modernism as a movement rejected the fixed and absolute aesthetic value of Realism, but it also assumed its own singular truth — the truth and the power of subjective experience. Artists took themselves as seriously as ever, as evidenced by the thoughts and works of Whitman, Elliot, Joyce, Salinger, Manet, Stein, Woolf, Yeats, Lawrence, and Picasso, just to name a few. Modernism championed the power of the artist's subjectivity over Realism's objectivity, believing aesthetic value was something subjective inside the artist, who could touch in with that experience and find a beauty whose power and insight could easily blow apart conventional ideas about what art was “supposed to” be. The power of art moved inward, from being “out there” in the world to being “inside” of the artist's own subjective experience. The same was happening in philosophy, in political theory, in economics, in the formulation of psychology, and in many other areas of human study.

Modernist art, which came to its greatest heights in the first half of the 20th Century, included “dissonant and atonal music, impressionism, surrealism, and expressionism in painting, literary realism, the stream of consciousness novel… [These works of art] seemed to open the imagination to a subjective world of experience ignored by the official cultures of societies that [were still] trying to hold onto traditional religious imagery and morality.”[6]

Modernism concerned itself with serious, existential themes. It assumed the true artist was also a true revolutionary, provocateur, intellectual, and philosopher bent on exposing a deeper, more grand and sometimes more dark truth. Artists like T.S. Elliot, Hemingway, Faulkner, Whitman, Joyce, Salinger, Manet, Stein, Yeats, Lawrence, Dickenson, Monet, Woolf, Picasso, and Salinger seemed larger than life because of how seriously they took themselves and their craft. And it worked — the early 20th Century boasts an awesome explosion of artistic insight and execution, not seen since the Renaissance, as artists in all areas — literature, theater, music, painting, sculpture, architecture — addressed life with the power of their subjective experience, expressed through a supreme confidence in their abilities. But Modernism's reign was a short one, and within half a century of its widespread acceptance, it was already being eclipsed by the next great movement in art and philosophy — postmodernism.

A Very Brief History of Postmodernism

We have seen how Modernism placed subjectivity at the core of its values. But Modernism, like Realism, also assumed that the artists' subjectivity was absolute and that it was real (see Figure 1.2). Postmodern thinkers took the next logical step, or the next logical differentiation, and took this idea to its conclusion: there was no truth “out there”, but there also was no truth “inside” either — truth was constructed by culture and imposed on people. There was no singular “truth” that all of us should know — objective or subjective.

Frederick Nietzsche is considered to be the first true postmodern philosopher, and for good reason, for it was Nietzsche who told us, very convincingly, there were no facts, only interpretations. Richard Tarnas:

Nietzsche [set forth the] relation of will to truth and knowledge: The rational intellect could not achieve objective truth, nor could any perspective ever be independent of interpretation of some sort. This was true not just for matters of morality, but for physics, too, which was but a specific perspective and exegesis to suit specific needs and desires. Every way of viewing the world was the product of hidden impulses. Every philosophy revealed not an impersonal system of thought, but an involuntary confession. Unconscious instinct, psychological motivation, linguistic distortion, cultural prejudice — these affected and defined every human perspective. Against the long Western tradition of asserting the unique validity of one system of concepts and beliefs [over another] — whether religious, scientific, or philosophical — that alone mirrors the Truth, Nietzsche set for a radical perspectivism: There exists a plurality of perspectives through which the world can be interpreted, and there is no authoritative independent criterion according to which one system can be determined to be more valid than others.[8]

Figure 1.2: Postmodernism

Aesthetic Beauty is…

- Arbitrary and non-fixed

- A construction of the artist

- Created by culture

- Determined by human view

Welcome to the postmodern world: reality, whether one thinks of it as subjective or objective, is nevertheless entirely constructed and arbitrary. The implications this had in the art world were profound, as we will see. One might begin to see now how Fountain was indeed making a powerful statement about our assumptions of what “art” is and what it isn't.

Postmodernism in art followed quickly on the heels of modernism; born arguably with Duchamp's Fountain in 1917, it nevertheless did not come into true maturity until the 1960's. Postmodern art mirrored the insights of Nietzsche: the rejection of the very idea that truth or beauty can ever be captured, or that any standards at all can be used to judge art. Postmodernism rejected the grand narratives that can be seen running through so much of modernist art, since those narratives assume a “truth” that can be discovered and expressed to an audience.

Literary irony and camp seemed to capture the sensibility of the time [the 1960's] rather than the seriousness of the modernist search for the alienated soul and the essence of reality…the idea of the avante-garde, of art as the most serious and truthful of cultural occupations, was increasingly abandoned, most famously by Pop Art in the work of Andy Warhol. The heroic distinction between high and low, fine art and commercial art, the truth-seeking avante-garde and the superficial, commercial marketplace was…abandoned in an anti-heroic embrace of pop culture.[9]

With this move, the self-important seriousness of the artist became self-parody. The larger-than-life artist became someone worthy not of respect but rather deserving derision. The artist as revolutionary became a joke, as did the very idea that something like “high” art could even exist. And soon enough the person spray-painting t-shirts at the beach was considered as much of an “artist” as the person whose work hung in the MOMA.

What was happening? Remember we discussed how, from the Renaissance onward, intellectuals were largely consumed with discovering the True (in science), the Good (in ethics/morality), and the Beautiful (in art). Postmodernism saw, correctly, that the True, the Good, and the Beautiful were largely constructed by culture, totally subjective (in the eye of the beholder), and not “true” in any objective sense of the word — Aboriginal art might use very different standards of what is “beautiful”, and who, the postmodernist asked, are we to tell them what is “really” art? Nietzsche, Marx, Freud, Einstein, Heisenberg, and many others presented so many powerful objections to “objectivity” existing at all that it was not long before a whole series of postmodern thinkers pushed these ideas to their conclusions.

For the postmodernist, truth and beauty and morality are something merely constructed, bound by culture, hemmed in by psychology, framed by gender, driven by economics, warped by language, distorted by the powerful, tied to the patriarchy and the domination of nature, and totally relative always. Only the naïve or those who wish to dominate believe in any kind of cross-cultural (or inherent) truth, cross-cultural (or inherent) beauty, cross-cultural (or inherent) morality, or a hierarchy of any kind. Saying something “is better than” something else to a postmodernist is interpreted as you unconsciously assuming a “truth out there” free of your own prejudices, which has been shown to be an impossible task. Therefore judgments of any kind (good, bad, better than) are considered the height of oppressive ignorance, the imposing of arbitrary standards onto someone else's “truth”.

Differences in Deconstructive and Constructive Postmodernism

To repeat: postmodernism as a whole tells us there are no cross-cultural absolute truths outside of biological/physical ones (for example men cannot, in any culture, give biological birth). As an example of how far-reaching this worldview can go, a deconstructive postmodernist might argue that gorillas are protected more passionately than reptiles only because they remind us of us. It is our own unconscious narcissism that makes us value them more than a shellfish or insect, not any inherent or innate value in gorillas themselves. Wanting to save gorillas instead of reptiles or insects or shellfish shows only your own bias towards things more “like you”, and not one thing more — they would argue gorillas and people and gnats are all equally “evolved” in the sense all three have had 4.5 billion years or so to develop. And this is true, sort of. A deconstructive postmodernist would stop here, and conclude that therefore gnats and shellfish and humans were of equal value. They deconstructed the ways we place value on things, and leave them in an undifferentiated heap of “everything/anything is as good as everything else.”

There is, it is worth noting, another important truth buried in this postmodern observation, one the constructive postmodernist would pick up: they would agree with the deconstructive postmodernist in the above paragraph, but add an important additional truth: Humans do indeed tend to unconsciously value things that demonstrate more complexity or more differentiation from the environment. We tend to intuitively realize that a gorilla is more complex than and more differentiated from a bacterium or, to make it even more obvious, a rock. Even though gorillas and gnats and humans and even rocks have all evolved for 4.5 billion years, there is a difference of complexity between them. Constructive postmodernism sees that a rock shows less complexity than a bacterium that shows less complexity than goldfish that shows less complexity than a human being — in other words, it sees a natural (not imposed) hierarchy of complexity. And so we do indeed tend to value greater complexity. And humans do indeed often equate greater complexity with greater value. This is why we often protect more passionately creatures that come closer to sharing our own complexity/depth (our children versus our pets, or our pets versus our plants). Constructive postmodernism, it is worth noting, is also the beginning of the Integral worldview, which we'll get into shortly.

The Positive Impact of Postmodernism

Before we go on to discuss where postmodern theory went too far, I must note how hugely important and beneficial postmodern thought was been. The positive impact of postmodernism has literally filled dozens of textbooks and I will, therefore, only briefly touch upon them here. Because postmodernism attacked the idea of a single truth, it followed that systems of oppression became suddenly much more visible. It's no coincidence that institutional racism, sexism, ageism, and many other “isms” came to be exposed in the decades after postmodern philosophers first began to write, eventually leading to a whole series of laws in the West to try and correct them. As but a tiny example, for the first time people began talking about how American history as it was taught was largely the perspective of the white, Anglo-Saxon males who had conquered it, and left out the very, very different perspectives of the Native Americans, people of color, women, and other marginalized groups. Clearly this is still something very much engaged in today, and clearly it is a hugely important, direct benefit of the insight and — dare I say — truth of the postmodern position.

Postmodern Art: Why Irony is So Important

All of this exposition was necessary so we can understand what is important to the postmodern critic, so we can therefore understand why Serrano's Piss Christ or menstrual fluids in beakers can be considered, by the postmodernist, legitimate art.

In the world of the postmodernist, truth and beauty in art are mere constructions, mere fabrications. They believe the very idea of truth and beauty imply a single standard of judgment, something that postmodernism rejects. Think of it this way: aesthetic beauty (the beauty of appearance) to an Australian Aborigine might be very different than a New York City playwright's which might be very different than a ranch hand's in southern Texas, which might be very different from yours. Postmodernism points out that any assumed standard for beauty is just that: an assumption that basically imposes its standards on everyone. And since art relies on aesthetic beauty as a major component of its appeal, that leaves the postmodernist with a real problem: what is attractive? What is art? Since art can no longer be judged on culturally constructed ideas of beauty, what is left? For postmodern art, irony is one of the only ways to express oneself that don't create direct contradiction — to mock and shock are what great postmodern art primarily does.

For the critics who praise postmodern art, value also comes through the scale of irony in a postmodernist piece. They look to see how deeply a piece of art pierces the collective consciousness and how much damage it does to the edifice of "established" culture. This helps to explain why Fountain is so highly praised — it went to the heart of the exaltation of art and, pun intended, pissed all over it. Guernica, on the other hand, is about Spain's experience during civil war under Franco as the Second World War closed in all around — something that is perhaps less relevant to a critic born in America when Jimmy Carter was in office.

Irony and its scale of impact, then, are very important in postmodern art. Another measure of value the postmodern critic uses is that the work in question be different – so long as an artist is different than the establishment their work gains automatic points. Critics see it as “daring to” stand apart from the “dominating” culture — menstrual fluids in beakers nailed to a wall as a kind of feminist protest against patriarchy, or so I assume. Beauty and truth? For the postmodernist, beauty and truth really can't exist, so for them beauty becomes the irony itself. Most of us have been to modern museums of art, and seen the rather dull geometric shapes painted onto canvases that are, at best, mildly interesting. These museums bore or confuse most of us, which is why they struggle to continue to exist and most would go out of business if it were not for wealthy benefactors. Much of the work inside their walls speaks to the head, to the postmodernists who “get” their irony and finds it attractive. But most of us agree that a triangle painted on a black canvas, or ink blots thrown across a wall, have nothing whatsoever to say to the heart, to the person looking for an emotional or even spiritual connection to a work.

Postmodern art's real power comes from forcing the receiver of the art to question their assumptions about what “art” is, about who and what and how art is created, and how it is received. Beauty and truth are left to antiquity, to the naïve who still believe in cross-cultural truths. In that sense Fountain can be said to have achieved success — it forced viewers to question, and often angrily dismiss, the work because it challenged their assumptions, destroyed their sacred cows, and in so doing influenced the next two generations of artists profoundly. And in this Duchamp's brilliance is simply without question. The question remains, though: is it art, or is it really something else?

Before we get to that, let us summarize: postmodern critics give points for irony, points for having a scale of impact, and points for coming from a different member of society (preferably no white heterosexual males, please). Fountain scores on irony and scale of impact; Serrano's Piss Christ scores on all three counts. Since the postmodernist finds irony itself beautiful they therefore consider Piss Christ and Fountain “art”. And yet if we remove shock, neither of these works offer any other evocative emotional response, because neither Fountain nor Piss Christ has any inherent beauty at all, which is why so many of us don't understand how these things can be considered “art”. Postmodernism, as we saw through our gorilla example, rejects inherent beauty and innate value as impossibilities — leaving them in a most peculiar and rather self-neutering place when it comes to judging how beautiful and valuable a work of art should be.

So the very questionable and very dull things we find in modern museums of art are, in fact, art to the postmodernist even if not for us, we must admit. But we can also admit that there can and should be better standards for art beyond irony, scale of impact, and social status of the artist. We must look once again for the Good, the True, and the Beautiful, if not in an absolute, at least in a relative way, for some things are relatively better or more true or more beautiful than others, even if all are indeed relative.

The Shadow of Postmodernism: Paradox, Flatland, and Narcissism

Let's take a look at the shortcomings of postmodernism a little more clearly so we can see where and how the Integral movement attempts to correct them. The great philosopher Huston Smith:

Relativism [the main tool of postmodernism] holds that one can never escape human subjectivity. It that were true, the statement itself would have no object value; it would fail by its own verdict. It happens, however, that human beings are quite capable of breaking out of subjectivity; were we unable to do so we would not know what subjectivity is…a dog is enclosed in its subjectivity, the proof being that it is unaware of its condition. If Freudian psychology declares that rationality is but a hypocritical cloak for repressed, unconscious drives, this statement falls under the same reproach; were Freudianism right on this point it would itself be no more than a front for id-inspired impulses. There is no need to run through the variations of relativism that arise from other versions of psychologizing, historicizing, sociologizing, or evolutionizing. Suffice it to say that few things are more absurd than to use the mind to accuse the mind, not just of some specific mistake, but in its entirety. If we are able to doubt, this is because we know its opposite; the very notion of illusion proves our access to reality in some degree.[10]

So too with art: it does not follow that judgments, standards, or ranking artwork are impossible, as Huston Smith so grandly points out. As Shakespeare said, therein lies the rub: postmodern critics fail to see that just being ironic and having impact isn't enough to make something art. To use only the postmodern criteria for art creates a flatland, where there is no way to deem anything “better than” anything else — everything is left in an egalitarian swamp where everyone gets a gold star for trying to be an artist, and everyone can be an artist if they want. Using irony just means you're on the “in” — you “get it”, which does, in fact, make your work a little better than grandma's painting of ducks in winter.

The postmodern critic stands over the deconstructed cannon of literature and art, and smugly pronounces “genius is dead”. Irony and mediocrity, freed from standards, are now able to dance happily into museums, performance halls, poetry slams, student textbooks, and all manner of narcissistic and mundane artistic expressions. Am I overstated this point? Go to a modern museum like the one in Denver, and when you see a giant ashtray full of cigarette butts (by Damien Hirst), ask yourself if you're in the presence of art or not.

|

| "Party Time", Damien Hirst |

And so I don't exclude literature, I would ask if anyone can really say they understood, much less enjoyed, slogging through Joyce's Finnigan's Wake or Pynchon's Mason & Dixon. These works, like so much of postmodernism, involves an intellectual slight-of-hand that passes off obscurity as insight and device as genius. Like giant ashtrays, they rely on the flatland of postmodernism to even be considered “art”, and not impenetrable excursions into the artist's self-indulgence.

It is using irony as the main criteria for judging art that is leading so many cutting-edge artistic institutions to cope with falling membership and declining interest — art has become an inside joke about an inside joke that fewer and fewer people are interested in hearing. Pynchon and DeDillo write primarily for postmodern critics and for lovers of postmodernism, but the rest of us, who think creative work should aspire beyond irony, find it flat, boring, and trite.

Postmodern Criticism of Established Art

As Ken Wilber once quipped, if you don't have the brains to build a building you can still burn one down. And postmodern criticism has, for too long, relied on burning down buildings, on deconstructing, as its primary tool. They have made their point. They have shown us a powerful truth. But the whole of art and literature, spanning thousands of years of human history, is more than just fodder for a fire. The classics are studied, still, not just because they were written by dead white men and current living white men want to perpetuate that power base. It is true that most pre-19th Century forms of art assume a single point of view, a single truth that was tied to an often-pretty-horrible-reality for a marginalized group or groups. Yet there is often a hugely important insight and staggering genius in the “classics” — to not study them institutionally borders on the self-destructive. The fact that most cultures in the past gave certain kinds of people more privileges than others to engage in art is an important fact worth studying, but it is also largely beside the point — it does not detract from the insights and genius of pre-19th Century pieces anymore than calculus is any less true because a white man (actually two white men), who were part of the patriarchy, invented it.

The Death of Postmodernism

In the final analysis, postmodern art has substituted aesthetic beauty with irony. And so it hugely confuses social commentary with art. It proudly announces that Genius is Dead, and mocks and deconstructs the very things it does not have the talent or the insight to create. All manner of ridiculous things are possible with this philosophy and, indeed, all manner of ridiculous things have been imposed on us. Some of you will recall an “artist” who put fish into a blender, and invited passersby to blend them to smithereens. What about this? Is this art? It certainly sparked a lively debate about the topic that, by and large, only served to further confuse the issue for just about everyone involved. I'll go ahead an answer it once and for all: it's not art, not even to the postmodernist — it is, at best, a grotesque social commentary, a gimmick designed to make people reflect on some cultural ideas. But art? No, not even by the standards of postmodernism we have already established — it shocks, yes, but it isn't ironic in any sense of the word.

The postmodern movement made a solid contribution by taking modernism to its logical conclusion; it serves us well by pointing out that all standards of judgment are based at least in part in some kind of cultural bias; it legitimately freed up unconscious and conscious systems of oppression that favored art from one kind of group over another kind. And it correctly pointed out that absolute standards in art, morals, or science are impossible — the standards themselves are not fixed and evolve, along with everything else in the known universe.

But while all these points are true, they can be taken to a point of self-contradiction and self-parody. For while it's accurate to say no standards can be held in a fixed manner, it is also accurate to say that some things can be relatively more true, more good, or more beautiful than other things, even if we can't speak about these things being rooted in an absolute. In fact, the very statement “there are no absolutes” is itself a statement that purports to be true for all cultures in all times in all places always — it cannot be true, because it violates its own stance.

The discoveries of the genetic component of disease, for instance, are more true than the mythologies of ancient medicine, which operated on ideas of bodily humours. Or in science, the idea that the earth rests on turtles “all the way down” is less true than the idea that the earth is in orbit around the sun — these are not equal “myths” of the universe at all. In morality, the idea that “all people are created equal” is better than the idea of “an eye for an eye” or “white males have the right to vote and own property,” or “slavery is morally just because the Bible says it is.” In art, Guernica is more beautiful than Fountain or Piss Christ, which actually have no intrinsic beauty at all.

|

| "Guernica", Picasso |

And so with this information, we move forward into the next great movement in art, not backwards to Modernism (“subjectivity is absolute”) or backwards further still to realism (“reality is absolute”) but forward, through the truths of postmodernism but away from its self-contradictions. In the place of postmodern flatness is a movement that once again believes art can be grand, inspirational, magnificent, emergent, and capable of speaking to most people, not just the hyper-educated elite. A new movement that believes the artist need not be an angry social outcast or critic or indifferent raconteur, but once again a revolutionary. Warhol, Litchenstein, and Pollock are dead, Serrano's mediocrity has been exposed in his banal commercial work, Thomas Pynchon and Don DeDillo continue to write for a singular audience who enjoy inside jokes about inside jokes. Let us turn the page, and leave these artists where they belong: in history books.

Beyond Postmodernism

So what, then, lies beyond postmodernism? Well, if postmodern insight centers around deconstructing unconscious meaning and imploding the very idea of an absolute, then the next movement would integrate that insight into a larger and more comprehensive understanding.

We've seen the insights of postmodernism, and its shortcomings. If we start with its insights (“all truths/art/morality are relative and context-dependant”) but reject its self-contradictions (“all truths/art/morality are equally socially constructed and therefore equal”), we have the beginning of the next wave of thought: integral, which can be defined as “being an essential part of something; without missing parts or elements.” We might add onto the true part of the postmodern statement: “most truths/art/morality are relative and context-dependant — and some are more true and less subjective than others.”

We can agree with postmodernism that all standards are arbitrary, that all criticism and all art (and morality and ideas of “truth”) are largely reflections of the culture in which they arise, and that all of us are largely immersed in our own subjectivity. But there are degrees of immersion — some of us are merely the products of our culture and not aware of it (the jingoistic American), but others (like many artists) are aware of their culture and because of this they can reflect upon it and criticize it! In other words, they are more differentiated from their culture than a child, or a bigot. No one can be entirely free from their culture, but we're not all equally blind either. So all of us are immersed to some degree in our culture, and have varying degrees of blindness around how we create meaning.

But we cannot stop there, for that leaves us with half of a truth — and it paralyzes us when it comes to criticism. In short, Integralism continues as we have seen, and says that some things are more true, more good, and more beautiful than others. It once again ranks, judges, and imposes a hierarchy onto things — but it does so without resorting to an absolute/unconscious standard of judgment. As I said before, the idea that science is just another myth among many is ridiculous, for it is more true that the earth orbits the sun that it is that the sun orbits the earth, or that the earth rests on the backs of turtles. In 1,000 years, there might be a truth that is far greater and more comprehensive than the earth orbits the sun. A sliding scale of relative truths.

| Physical | Cultural Organization | Worldview | Artist Expression | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Less Complex/ More Fundamental --> More Complex/ More Significant |

Atom Molecule Bacterium Plant Dog Ape Homo-Erectus Homo-Sapiens |

Survival Clan Ethnic Tribe Feudal Empire Nation-State Corporate State Value Community Global Community |

Animistic Mythical Mythic-Rational Scientific-Rational Pluralistic Holistic Integral |

Mythic-Literal Realism Modernism Postmodernism Integral |

It is VERY IMPORTANT to note that these hierarchies are value-free — that is, we can no longer unconsciously value greater complexity without knowing that we're doing just that. So complexity and value are not necessarily the same, but they certainly can be. I would argue that the postmodernists are unconsciously valuing greater complexity, without having any idea that's what they're doing (why else would they believe what they believe if it wasn't better than what others believed?).

Now, this same idea applies to art and art criticism. Some things are indeed more beautiful than others, depending on what standards are used. Is the Mona Lisa more beautiful than the afore-mentioned “artist's” work of fish in blenders? Of course it is, unless your only standard for “art” is “controversy”, in which case the mutilated fish are more “beautiful”.

|

|

| "Mona Lisa", Leonardo da Vinci | "Fish in blender", Marco Evaristti |

Integralism agrees with postmodernism on many key points, including:

- The aesthetics of art is not absolute or fixed

- Meaning is context-dependant (in other words, there is no meaning in-and-of-itself, but only in-context with something — viewer, culture, artist's state of mind, etc.)

- Irony and humor can be a powerful part of art

- Standards of judgment are immersed in the culture in which they arise

- “Good” art can cause the viewer to question their assumptions about a number of things, including their assumptions about what makes “art”

- Reality is made up of many points of view and many perspectives, and none are absolutely “correct”

- The “dominant” group needs to take efforts to ensure it is not intentionally or unintentionally excluding marginalized perspectives/people

- Art criticism is very problematic if it does not “own” its assumptions about what is and is not “art”

Integralism disagrees with postmodernism on this:

- Complexity and skill of execution can and do exist, and are the single most important things to consider in judging art

- Judging and ranking art is not “impossibly one-sided”, or synonymous with marginalizing the work, the artist, or the culture in which it arose

- Art arises out of and exists as part of the artist, the culture, and the viewer equally

- Standards are needed and necessary to judge something “good art”, “bad art”, or just plain “not art”

- These standards can avoid becoming dogmatic by having them explicitly stated by the reviewer/critic

- Reality is made up of many points of view and many perspectives, and none are absolutely “correct” but some perspectives have greater depth/insight than others

- Likewise, meaning/beauty are constructed but some constructs are more true than others (as Ken Wilber says, “Hamlet” is not about a troupe of girl scouts no matter how one interprets it or in what culture)

- Aesthetic beauty is both in the artist (subjective) and in the culture (objective)

- Irony/humor are not the same as aesthetic beauty; conflating them allows social commentary to pass as artwork. Art must also possess complexity and skill of execution.

- The “dominant” group needs to take efforts to ensure it is not intentionally or unintentionally excluding marginalized perspectives/people — but it does not necessarily need to reject its own (admittedly relative) standards of aesthetic value

- Grand narratives are still possible, since even postmodernism claims to be “more true than” modernism — Integralism states explicitly it is more true than postmodernism, but acknowledges there will be future movements/insights more true than it

- It is possible to ethically and honestly judge any work of art, so long as one acknowledges what criteria they are using and what standard they are holding to work to (this is an important point, and unpacked with some examples below)

| Realism | Modernism | Postmodernism | Integralism |

|---|---|---|---|

Aesthetic Beauty is…

|

Aesthetic Beauty is…

|

Aesthetic Beauty is…

|

Aesthetic Beauty is…

|

The meaning of art is…

|

The meaning of art is…

|

The meaning of art is…

|

The meaning of art is…

|

Integral Art

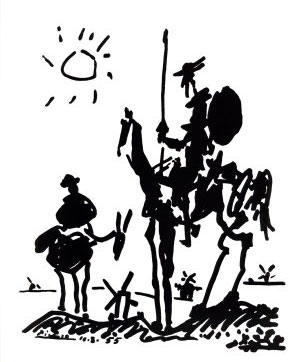

What is Integral art? Integral art comes down to a demonstration of complexity and the skill of execution. Which doesn't mean it has to be explicitly complex — Picasso's drawing of Don Quixote, for instance, is simple, but its simplicity demonstrates the incredible internalized knowledge of the artist. It is both complex and skillful despite the fact that it is a “simple” line drawing. Just as Modern art is “beyond” Realism, so too Integral art must be “beyond” postmodernism. This can only be determined on a case-by-case basis. Is Don Quixote a “modernist” work? Yes, it is. But why?

|

| "Don Quixote", Picasso |

Four things must be considered when evaluating artwork:

- the artist him or herself and what they think the work is (prevents critic projection)

- the cultural view of the artwork — aboriginal art in Brazil versus Serrano in NYC

- the artwork itself

- the viewer's response

If you look at any one of these things alone, it is impossible to determine with much accuracy what's going on in the artwork. Ken Wilber, for instance, is quite brilliant and complex-of-thought, yet as far as I know has little talent with a paintbrush (sorry, Ken). So if he draws a stick figure he says is “integral”, #'s 2, 3 and 4 would all dictate that the work actually lacked complexity and skill of execution — and therefore isn't art — even though the man himself maintains that it is.

Integral art rejects one of the single most limiting factors of postmodernism — that standards, judgments, and qualitative distinctions are impossible. Integral art does not embrace modernism (which would be moving backwards), and assume a single truth (the artist's subjectivity), but rather sees a continuum of sliding truths, sliding contexts, sliding meanings. These, though, do not land the artist and the critic and the viewer in aperspectival madness, but rather orient them to an important insight: there is no SINGLE standard for great literature, great art, great music, etc. But there are some standards, and some are better than others even if all of them are relative in their own way. So, as a terribly obvious example, an accountant banging on a drum in a drunken fit is clearly not music, and even more clearly requires far less talent than composing an opera. It is a difference of complexity and of skill of execution.

Integral art once again makes a distinction between “high” and “low” art, rejecting the postmodern fusion of the two. Is a Daniel Steele novel the same as a Richard Powers one — both are simply fiction, and who are we to determine which is better? No — a Richard Power's novel has greater complexity and greater skill of execution, both of plot and of character, and therefore deserves to be viewed with greater care and yes, with greater value, at least from an Integral perspective. If your criteria for “high” art were “entertainment”, then the Danielle Steele novel might score higher, but the Integral critic would reject this definition of “high” art as inadequate.

How complexity is executed is also a matter for criticism and judgment — Joyce's Ulysses is a difficult and complex book and open to debate, but his last work, Finnegan's Wake, is an impenetrable mess. Complex, yes. Executed skillfully, no. So the value judgment (“an impenetrable mess”) would consider it, essentially, “bad art”. Does that mean a Danielle Steele novel is better than it? It might, or it might not. There is no set “formula” for any of this.

So by these standards we can see that the Integral artist and critic can come to make meaning once again, and come to make critical distinctions that are based on more than the limited breadth of postmodernism.

Integral Art Criticism

The trouble with postmodern criticism is that it still does what it criticizes others for: namely, it either imposes its own standards onto all artwork (that they be ironic, etc.) or it refuses to offer any intelligent criticism at all, neutering its own stance. Clearly neither one of these approaches is effective or helpful in picking good artwork to study, review, anthologize, etc.

Readers interested in more detail might note Ken Wilber's comments on the state of art criticism:

“[All] artwork exists in contexts with contexts within contexts, endlessly…and each context will confer a different meaning on the artwork precisely because all meaning is context-bound: change the context, you elicit a different meaning. Thus all…[postmodern art analysis] theories — representational, intentional, formalist, reception and response, symptomatic — are basically correct; they are all pointing to a specific context in which the artwork rests…the only reason these theories disagree with each other is that each one of them is trying to make its context the only real or important context…” [11]

Integral art criticism offers reviews of artwork in two ways. It first ascertains what sort of criteria the artist and the artist's culture expect of “art”. So in other words it would review Realist work using the criteria of Realism, Modernist work using the criteria of modernism, and postmodern work using the criteria of postmodernism. Its “value judgment” would make explicit what it was using to determine something as “good”, “not so good” or just plain “bad”. It would do this rather than subject all artwork to the same set of standards. And of course this also can work when reviewing artwork that comes from outside of the reviewer's culture — one would first find out, for instance, what the criteria for “good” artwork is in, say, Afghanistan, and then attempt to review the work within the cultural guidelines of its mother country. The book The Kite Runner therefore passes the test here, and could be considered “good” local art if one considered pre-Soviet Afghanistan's artistic culture. Most importantly, the Integral critic would make their bases for judgment explicit, so that the reader would be able to agree or disagree with the reviewer's assumptions before they offer positive or negative criticism.

However, this is not enough. The work must also be judged according to the standards of the reviewer's culture — in much of the English-speaking world, this would mean a novel, for instance, would be expected to have a strong plot, strong characters, clear narration, and may use various literary devices such magic realism (a postmodern invention), stream-of-consciousness writing (a modernist invention), etc. And so Kite Runner once again passes the bar, and rightfully satisfies Western critics. Kite Runner is, basically, a work of Realism, and by the standards to that kind of art, it succeeds very, very well. It is not an Integral work of art, meaning it does not build intentionally (explicitly or implicitly) upon the strengths and weaknesses of postmodernism.

As another example, let's move to the much-maligned Piss Christ. An Integral critic would note of Serrano's Piss Christ that it does, in fact, constitute art for a postmodernist, but for a postmodernist only. For Piss Christ, as we have already discussed in detail, offers only irony, a good scale of impact, and an artist outside the mainstream — hallmarks for “good” postmodern art. But the Integral critic might point out that it offers little complexity (rather obvious social target — religion) and offers little skill of execution. So it is decidedly not-integral, and by the standards of Integral art, is not art at all but rather tepid social commentary.

This essay is meant to be an overview of these topics, a simple starting point that attempts to nudge us out of postmodernism and onto the next great wave of art and its criticism. It is my hope that more capable minds than mine will begin a lively debate on these topics, and help to further define art and art criticism for the 21st Century.

References

[1] Douglas Cruickshank, "The FBI's new secret weapon: Snide prose", www.salon.com

[2] "Duchamp's urinal tops art survey", news.bbc.co.uk, December 1, 2004

[3] University of Bologna, Wikipedia.org

[4] Richard Tarnas, The Passion of the Western Mind, (New York: Ballantine Books, 1991), p. 224

[5] Ibid., p. 345

[6] Lawrence Cahoone, From Modernism to Postmodernism, An Anthology (Cambridge, Blackwell Publishers, 1996), p. 7

[7] The Passion of the Western Mind, p. 370

[8] Ibid., p. 370

[9] From Modernism to Postmodernism, p. 8

[10] Huston Smith, Beyond the Post-Modern Mind, 2nd Edition (London, Quest Books, 1989), pgs. 217-218

[11] Ken Wilber, The Eye of Spirit, (Boston, Shambhala Publications, 1997), pgs 112-113

Links (in order of appearance)

- Marcel Duchamp - Fountain

- Picasso - Les Demoiselles d'Avignon

- Picasso - Guernica

- Campbell - Soup labels

- Serrano - Piss Christ

- Leon Battista Alberti

- Filippo Brunelleschi

- Petrarch

- Damien Hirst - Giant Ashtray

- James Joyce - Finnigan's Wake

- Pynchon - Mason & Dixon

- Marco Evaristti - Fish in a blender

- Picasso - Don Quixote

- James Joyce - Ulysses

- Khaled Hosseini - The Kite Runner