TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Truth, Beauty

and Fluidity

Robert Kernodle

We are water-based creatures of a water-based world. Water is our most common connection.

Is truth a thing? Is beauty an object?

Demanding that either idea conform to rigid boundaries might have caused some modern thinkers to reject them both. What a tragic demise for art! Even more, a tragic demise for the human senses! Most of all, this denial of beauty has been a tragic contradiction, because such denial is as rigid a boundary as the boundary being denied.

Any attempt to treat ideas as hardened shells seems doomed this way. Opposing sides of an idea shell develop, fail to mesh, and this failing enacts itself as the only common ground. “Agree to disagree” is the hallmark plea. A better way to share the world might loom before us; it always has. We only need to focus on the most basic observations to see it.

The Solid Trap

Consider that an unspoken bias has fashioned much of modern thinking, a bias so ingrained that we have embodied it into an unconscious reflex. This reflex has dominated how we conceptualize anything and everything. Call it the “solid bias” or “encapsulating bias”. This “solid bias” has caused two main actions: (1) defining categories, and (2) demolishing those categories, only to deny any category an honored place. In the first action, separate conceptual spheres came into being, juxtaposed like marbles in a bag. In the second action, all conceptual spheres exploded into an amorphous mass with no connecting dynamic to relate anything to anything else meaningfully.

Marbles or amorphous mass? Which treatment of categories should we choose? At first, there seems to be no other choice, and this first response has prolonged the dilemma of modern artistic thinking.

Power of the Sphere

The worldview guiding our most advanced culture has grown from the shape of a sphere. This geometrical form secretly rules how we establish ideas. From numbers, to atoms, planets, and stars, we unknowingly assert spherical boundaries to focus our attention. We further define these spheres by imagining voids in between them.

This worldview has encouraged a mindset of defining everyday, useful words as hard-bounded spheres (atoms of thought, so to speak). The word, “art”, itself has suffered from this atomic mindset, a mindset that revolutionary thinkers tried to pulverize by obliterating conceptual spheres altogether, offering no effective organizing replacement. This pulverizing of categories has left artistic conceptualizing in an angst-filled, impotent position (or non-position) of not committing to any sense of beauty, even less to any sense of shared beauty. Shared beauty recently became a lie, and, ironically, this lie became the new truth.

Atomizing reality is not the problem, however, because conceptualizing within boundaries is the very nature of human consciousness. A hardened shell of a skull surrounds a soft, flexible brain, whose mental functioning mirrors its anatomical form. Concepts themselves are spherical encasements of thought born of visual transmissions through circular orbs (eyes) relayed to a brain rigidly encased. In a sense, we see our skull's sphere-like reflection and our eye's circular frame in everything we label.

Between Spheres

The problem, then, might lie in applying circular boundaries exclusively, without considering equally the motion between them. The invisible flaw might be in not stepping back often enough to see that spheres form particles of a fluid, and fluid laws apply in creating shapes, patterns, purpose and meaning.

Why, at a particular time in history, did “universal truth” and “universal beauty” fall out of favor? A decisive campaign deemed these as impossible. Yet the phrases themselves and our ability to continue uttering “truth” or “beauty” echoed a universal grasp of what they might mean. How could we deny beauty and truth, if first we could not retain this deep, shared understanding of what they might be? How could we argue against their universal nature, unless we admitted to their possibility, against which we might argue universally? How could we speak of our disagreement, unless we agreed on how to speak at all? Something shared has been going on all the while. Discord has had a universal instrument, and that instrument has been the human body.

The Body's Depth

Any claim (or even refusal to make a claim) must presume that we have a common understanding of the words in use. We, therefore, share the medium of words. We share a common bodily structure from which these words erupt. Our bodily structure (by many reasoned accounts) developed from the ocean, common ancestor to all life, as we know it. The human body is 70% water; the Earth's surface is 75%. We are water-based creatures of a water-based world. Water is our most common connection. Words bubble out from our body's water-based structure. Similar life giving currents course through our veins. Similar anatomical motions and kinesthetic behaviors flow from our limbs. We recognize one another as being of the same humanity. Perhaps a significant number of us have lost touch (literally) with the truth of this humanity.

What Truth Is

One definition of “truth” is “what is real”. What is real is the fluid nature of body, life and world. More profoundly, this truth extends beyond our shared bodily structure and past our immediate terrestrial surroundings. Modern science reveals that 99% of the visible universe is plasma, the so-called “fourth state of matter”, which acts like a fluid. In other words, the whole universe seems to be fluid. Truth stares us in the face from the stars to the sea. Little wonder why we find seascapes and starry nights so beautiful. Who does not marvel at oceans and skies? Fluid beauty, thus, follows from fluid truth.

The whole, connected truth is that a fluid universe created solid skulls in bounded bodies whose minds became obsessed with their solidity. Once trapped in solid obsessions, primal fluid creatures longed for primal flowing freedom. As a result, they burst from categorical boundaries, demolishing solid concepts into turbulent conceptual goo devoid of common currents. Fluid mind overlooked the truth that solidity arises from fluidity and returns again, only to arise yet again in a defined solid form related to the whole.

Polarity is not Static

The fault of modern thinking has been in choosing to ignore one aspect of reality exclusively in favor of another, then rejecting that aspect in an unconscious reflexive rhythm to go the other way. Such thinking has converged only on one conceptual pole at a time, when (in truth) reality oscillates between two poles, requiring a similar conceptual rhythm to grasp it. In other words, in our search for, or rejection of truth, we have been too one sided. Modern aesthetic theory, therefore, has not rejected beauty so much as simply misunderstanding it from the start.

The problem, again, is in those spheres that we have implanted so well in our ways of thinking. When we fail to maintain concepts as solid, impervious spheres, we reject concepts. Even more, we eventually reject the concept of “concept”, which itself is the most constricting concept of all (that is, the concept disabling all other concepts except itself).

Suppose, though, that concepts never have been such impervious spheres. We were mistaken in thinking that they ever were. Suppose that concepts form like whirlpools and bubbles from a fluid of perceptual possibilities; they stabilize in relationships with one another, subtly exchanging intervening materials like soft cells with pervious membranes, adapting, evolving, dissipating, and reforming with deep resonances constantly recurring throughout eternity. Suppose that the true geometry (the primitive geometry) of beauty is non-Euclidean, non-linear, and somewhat buried in complexity like a strange attractor, where classical forms are special cases of those attractors revealing their sensory effects. How humane it feels to speculate that our classical sense of beauty arose from such fluidity.

Perhaps at a critical place in art history, we trapped ourselves in our heads, loosing touch with the fluid, organic body from which the head extends. While trapped in the head and its conceptual categories, we gradually lost touch with a physical, sensual body whose perceptions originally informed our ideas about beauty. Increasing societal compartmentalizing, atomizing and quantizing enabled further fragmenting of body from its senses of self and world. Breaking out of this new perceptual prison was the survival instinct of a body trying to reclaim its whole self. Alas, the effect was that of a severed head, too far separated from the body feeding it. The body now ran about like the proverbial chicken with its head cut off, staggering in confused denial of previous categories, stumbling in blindness of its now headless self, completely dissected from the sense of beauty that first infused it. Such has been the seemingly debilitating offshoot of the atomic mindset. As useful as it has been for organizing our control of nature, it also has been instrumental in disintegrating our deep connection to nature.

Feeling the Flow

Whether we think of nature as Earth, the cosmos or God, nature produced the human body. The human body produced language. Language arose from shared harmonies of the body and from the need to communicate or repeat these harmonies. Song and dance emerged like drops of sweat on the shared flesh of being. Proportions of this nature-born body found their way into architecture, the structures that contain or nurture bodies. Rhythms resonant with this nature-born body found their way into drums, music and ceremony. These proportions and rhythms ultimately came from our common birthplace of water, which in turn came from a cosmic place very much like water—the universal fluid plasma.

So powerful is the human intuitive grasp of fluid, that most of the world's religions base their creative myths on it. How universal! That separate cultures could arrive at this same conclusion in their most primal beliefs is remarkable. The body in touch with itself, thus, knows its most basic self as fluid. The body's mind, if fully connected (not completely severed), threads this fluid intuition through all its perceptions.

On the other hand, if we are to atomize the body preferentially, then we must concede that the world's stuff is 99.999999999999 % empty space. This is the immense smallness of conceptualized atomic particles and the immense supposed void in between them. How strange it feels to our senses to commit to a proposition saying that our physical selves are actually empty, that our very skin is mostly not there. How could we possibly find truth or beauty in such emptiness?

At this point, we might refer to Eastern philosophy for an answer. The Buddhist saying, “Emptiness is form, and form is emptiness”, seems fitting here. Such a saying certainly strikes a chord of approval in our modern acceptance of language enigmas. But how does this really help a mind's body tangibly struggling for purpose in a world laid meaningless and abandoned by beauty?

Consider what has both form and formlessness in one: the same fluid that the world's religions offer. Consider what has both concentrated centers with vast spaces in between them: a fluid mass, speckled with vortices and other formations spawned within its continuity.

Einstein flirted with this sense of things in making matter, time and space more malleable, but did he take it far enough? Quantum theorists sometimes spoke of a foam-like foundation of reality (if they uttered the term, “reality”, at all), but did they fall short of admitting that their math merely mapped a more fully liquid existence? Is all the 99.999999999999 % of atomic space another sort of fluid? Is quantum foam actually froth on a smoother fluid still? And what about the latest, “dark matter”—matter that we know is there but cannot sense? By denying our physical senses their equal consideration in this matter, are we letting a more beautiful idea slide right past us?

Reawakening the Senses

Elusiveness often is the way of beauty, to exist under our noses, and only in an instant reveal itself. “Alethea”, the ancient Greeks called it, is the sudden revelation of truth, reality, beauty for what it is and can only be. Such beauty (out of view) flows all around us, until circumstances align to unveil it. Such beauty becomes visible to bodies wholly opening up and receiving tactile perceptions released from the skull's encapsulating control. Such beauty transmits through our inner fluid's knowledge of itself.

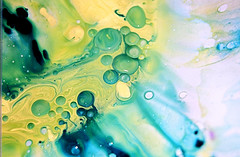

A person need only drop oil on water to see nature's most basic beautiful forms emerge. Circular globs float for a moment with space in between, not unlike atoms, stars and planets floating in their respective “voids”. These liquid circles are cousins of the very spheres that can concretize our conceptions. Displace them by adding more liquid and colored pigments, then observe. Amazing things start to happen. Unplanned curves and compositions present themselves. Tiny streams, filaments, blobs, bubbles and island-like formations arise amidst spontaneous color gradations. Bubbles, recall, are none other than spheres that form in fluids! What bursts and further disrupts them into disorganized ugliness soon reorganizes the mixture into new organic patterns that human eyes newly judge as beautiful. A beauty more complex than mere spheres, thereby, arises. A medium more complex than mere space between these spheres, likewise, unfolds.

Not every appearance of this medium is equally beautiful, however. Even in this greater complexity, anything and everything does not count as beauty. There seem to be best complex shapes, best complex colors, best complex designs that the human body knows by feel. The rules of beauty's full complexity reside in the body's fluidity and engage through the body's visceral senses.

So what is this sense called “beauty” that our bodies intuitively grasp? How are we to think of such a sense, if not in solid terms? Beauty cannot exist in a void between the solids -- this is basic contradiction. Since existence cannot even exist in a void, a void must be a substance too, in order to be at all. A sense of beauty, thus, must have tangibility, a substance that it touches, or physicality, … not a solid or bunch of solids, but a fluid continuity. Beauty must exist in the body's chemistry, perhaps as a certain shape of wave or wave train pulsing through our life's liquidity. Beauty is organization that comes to bear on all fluid beings. Beauty is a shape deep in substance's motion, a ripple, not a static thing— forms or patterns of change itself that strike a common chord in its varied entities.

But how can something moving somehow be the same in separate identities? The answer, once again, lies in seeing truth as fluid reality. Nothing that is real is completely separate, from the very beginning. All is one of the same liquidity. Each different expression of this sameness stands in relation with every other expression of it. Like waves of different lengths, like blobs with different shapes, all of reality's patterns float and contort in the same fluid mass of eternity. Beauty is a best relationship between these patterns and human perceptions. Beauty is not a “thing”, but a “then”, not a “what”, but a “when”. It is when liquid bodies (well attuned) sense their harmonic alignment with the greater cosmic sea.

|