|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Helen Davis has spent 22 years as a university lecturer researching and teaching business management, organisational psychology and human resources management to line managers and HR personnel studying for their professional qualifications at Masters level. She has had her own business as a management and training consultant, and is also a qualified psychotherapy counsellor. She has an MBA and a Masters degree in Human Resource Strategies, but the material for this monograph has mostly come from the real life experiences of hundreds of line managers and HR professionals she has met and taught over the years. She is now retired and lives in Hertfordshire, UK. She has had an interest in Integral studies since the 90s. Helen Davis has spent 22 years as a university lecturer researching and teaching business management, organisational psychology and human resources management to line managers and HR personnel studying for their professional qualifications at Masters level. She has had her own business as a management and training consultant, and is also a qualified psychotherapy counsellor. She has an MBA and a Masters degree in Human Resource Strategies, but the material for this monograph has mostly come from the real life experiences of hundreds of line managers and HR professionals she has met and taught over the years. She is now retired and lives in Hertfordshire, UK. She has had an interest in Integral studies since the 90s.

APPLYING THE AQAL MODEL TO CHOOSING, TRAINING AND APPRAISING ORGANISATIONAL MANAGERSHelen DavisIntroductionSome of you may recall a recent essay which I submitted to this website entitled 'The Managers We Deserve'. Along with details about how I had applied the AQAL model to the topic of management capabilities and the consequent results, there was much in there about management generally, which may not have been of any particular interest to readers. I have therefore summarised that essay, concentrating purely on the aspects that may be of interest to Integralists. This is what follows: In the course of carrying out research into improving the effectiveness of organisational management in the UK, I investigated the way in which organisations choose the 'capabilities' they require their managers to have; 'capabilities' consisting of knowledge (know-how, know-what, know-why), skills, attitudes and types of behaviours. As a result I applied the AQAL model to the whole subject, comparing the results with advice given in the existing academic and professional literature. The outcomes suggest that organisations could be approaching the topic more effectively. Overview and backgroundWithin the existing AQAL literature on organisations (e.g. Edwards 2008; Morris 2009, Divine 2009; Hunt 2009 and Esbjorn-Hargens 2010,) the UL has come to indicate the personal qualities of any individual working in an organisation, and the UR indicates individuals' behaviours and concrete achievements. The LR indicates the systems and structures that operate both within the organisation and between the organisation and its environment, and LL indicates the organisation's shared values and its overall attitude to change and learning.

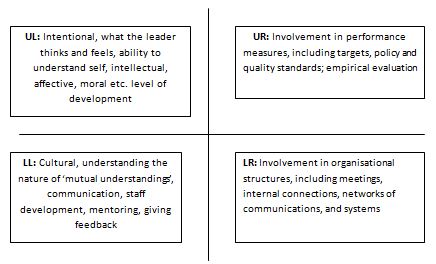

The four quadrants have also been applied to the activities of leaders of organisations as follows:

Figure 1: adapted from Morris, 2009: The Four Quadrants Applied to Leadership

The capabilities needed by a manager for the activities listed in the LL and LR of this diagram could all in fact be represented in the UL and UR, as they would be capabilities that only an individual (in this case 'a leader'), can have. This is not to dismiss collective management capabilities, which I shall return to again below. On the other hand, although most the capabilities desired in its managers as individuals by an organisation are by definition only going to fall into the two upper, individual quadrants, the selection of exactly which capabilities are to be included is likely to be heavily influenced by the conditions and circumstances applying in the two lower collective quadrants i.e. the culture, structure and systems in place within that organisation. For example, an organisation with a culture, structure and processes associated with high performance working (as defined by the CIPD, 2005) would do well to specify good interpersonal skills as an 'input' capability in any new managers it takes on. Integralists know that every quadrant influences every other quadrant. The four quadrants 'tetra-arise' or develop together, as individual attitudes in the UL and individual behaviours in the UR in turn feed back into the collective cultures and structures of the LL and LR. There is a further consideration here, to which the two lower, collective quadrants specifically draw our attention. Organisations usually hire individuals as managers rather than groups or teams, but many organisations have occasion to select management consultants, or have to decide to whom to outsource management. These two options will as much involve a choice, conscious or otherwise, of particular capabilities as selecting one individual does. Furthermore it is not unusual for whole groups or teams of managers to be put through development or assessment centres, again based on desirable management capabilities. It is accepted that a team's performance can be better or worse than the sum of the performance of its members and one of things that a selector might be looking for is that the team as a whole has the ability to cover all the roles necessary for success. Relating the LL to the UL, Ken Wilber has stated (2006) that a culture is simply a reflection of the stage at which the predominant number of people within that stage are at personally. However, most writers on organisational culture, (such as Charles Handy 1993,) are of the opinion that an organisation's culture is affected by more than simply the individuals within it, e.g. the industrial sector within which it operates, the context etc.- in other words, the LR quadrant! And while all members of an organisation shape its dominant culture, it is often the senior managers that determine the overall culture of the organisation, as they have the most power. In view of earlier remarks concerning the 'tetra-arising' of all four quadrants together, one must not forget that organisational cultures will in turn have a significant influence on which people it chooses to become senior managers. One can also see how each quadrant can fulfil another function in this analysis, and that is concerning the areas of knowledge and skill that each quadrant indicates a manager (or leader) might usefully have. In this way the four quadrants can act as a useful 'checklist', as Morris uses them in the diagram above. For example: Does the manager understand the different values and attitudes that individuals can have, and how best to develop each employee's knowledge and skills (UL)? Do they have the ability to successfully performance manage individuals (UR)? Do they understand the organisation's environment, its industrial sector, its internal systems and structures and operate successfully within them (LR)? Do they understand how to manage and develop organisational culture (LL)? Applying the upper left and upper right quadrants furtherUsing the AQAL model, I divided management capabilities into two categories. The first category, those that can be defined as 'upper left' can be called 'input' capabilities. These are the existing capabilities with which a candidate arrives, and which are ready to be applied to any particular job. This category therefore includes the candidate's knowledge, skills, attitudes and personality traits. Some attitudes, personality traits and skills are innate, and are considered by many to be fairly immutable. Other attitudes, traits and skills can be developed, as of course can knowledge. The second category, those that can be defined as 'upper right' can be called behavioural categories. When recruiting, these capabilities are relevant to the assessment and examination of the candidate's likely behaviours in certain situations. When it comes to performance-managing the appointed candidate, it relates to the actual behaviours exhibited and observable. Examples of 'input' capabilities include: knowledge of the sort of work involved; the ability to drive a car; advanced interpersonal skills; a 'can do' attitude; an open and trusting personality. Examples of 'behaviour' capabilities include: managing time effectively; being a good team player; behaving fairly towards all staff; keeping meticulous records; never being late for an appointment. For a long time in the UK the 'input' category of capabilities was considered very important in both the selection of candidates and as the basis for the appraisals and ratings of existing managers. Then there was a shift towards behavioural capabilities. Mostly, in such behaviour-oriented interviews, the candidate is assessed by asking what they've done in certain situations in the past, and/or how they would behave if certain situations occur within the job for which they are applying. The problem with behaviour based interviews is that most intelligent candidates know very well what they should reply to the questions they are asked, even if they have never behaved, nor intend to behave, in the way they describe. Sometimes assessment centres are set up to see what happens when a candidate is placed in a particular situation. This seems preferable, because such an environment is a more reliable test of the candidate's reaction to actual situations. It at least has the possibility of revealing any gap between the candidate's declarations and actual performance. It is more expensive of course, but nothing like as expensive as recruiting the wrong person. One must also bear in mind that some candidates turn out in hindsight to have been very good actors, and this includes certain varieties of sociopaths. It is for this reason that I would include psychometric and other appropriate testing for input capabilities, particularly the innate ones, for all management candidates. This would include screening for undesirable as well as desirable characteristics. Ideally, the assessment process should include tests for input capabilities and behaviours, (and again I would remind readers of the financial and human costs of getting the wrong candidate in post.) There are also serious diversity and equal opportunity issues here. A potential candidate for a managerial post may find that a previous lack of opportunity for demonstrating certain behaviours (that lack of opportunity being occasioned by the candidate's gender, ethnicity etc.) prevents them being judged as suitable for the position, and so a vicious, self-perpetuating cycle operates. If the candidate has the appropriate input capabilities, they could probably pick up the required behaviours very quickly. Given that there is currently a real problem in finding suitable talent for many posts, even with high unemployment, we have another good reason for including input capabilities in assessing candidates (quite apart from the moral arguments). And there is yet another argument for paying close attention to a candidate's input capabilities, especially the innate ones. There is research which demonstrates that if certain innate capabilities are not present in a person, there are various behaviours which it will not be possible to develop in him or her, sometimes not at all, sometimes only over years. This would be borne out by the application of various 'lines of development' theories which could be applied to this quadrant, including Kegan's, Torbert's, Cook-Greuter's and of course, Ken Wilber's. That said, we must also bear in mind that possessing certain input capabilities is not an infallible guarantee of certain behaviours. The same person will behave differently in different situations, depending on the context. So including input and behavioural capabilities in our lists of desirable management capabilities seems to be the best way to proceed here. It is also important to distinguish them, as the preceding paragraphs demonstrate. Very many lists of capabilities, including those drawn up by experts, academic and otherwise, do not make this distinction, which I personally think leads to some very confused thinking and decision-making. Note the difference here between a behavioural capability and an activity: “attending meetings with other managers” is an activity; “communicating well with other managers” is a behavioural capability. Note also the difference between a behavioural capability and a goal. Examples of goals include: increases production by 10% each year; produces certain required information on the 20th of every month; keeps costs within a certain limit on a particular project. The distinction is important. The goals which you want a manager to achieve will determine the activities you expect him or her to carry out, and those in turn will influence the behavioural and input capabilities you will look for in the postholder. So, a word of terminological warning here: Some writers on management refer to behaviours as 'input competencies/capabilitiess' because they result in activities and goals. Activities and goals are referred to as output or outcome 'competences'. This terminology has not been particularly helpful in distinguishing between actual observable behaviours on the one hand, and innate capabilities on the other, which the discussion above reveals as particularly important. Applying the LL quadrant to popular management literature on organisational cultureThe idea of cultural values 'evolving' is standard to the AQAL model. From my own reading, I would suggest that parallels can be drawn between the stages of development described by Wilber/Spiral Dynamics and Harrison's four types of organisational culture (1984, taken up and developed by Charles Handy in his popular textbook 'Understanding Organizations' 1993). Harrison's 'power culture' equates to Spiral Dynamics' warrior stage, his 'role culture' is the equivalent of a traditional culture, his 'achievement culture' (Handy's 'task' culture) is 'modern' and his 'support culture' (which he originally referred to as 'affiliative') is postmodern/pluralist. Harrison does not mention developmental stages, but it is interesting that in a pamphlet for AMED in 1987 he writes about each organisational culture in the same order as they appear in Spiral Dynamics. Application to the LR quadrant: Can a good manager manage anything?No. Or rather, I would say it depends on what level of the organisation we're talking about. This will affect the capabilities needed as specified in the UL and UR quadrants In the UK, there still exists a strange propensity within organisations to promote people to management level because they have good technical skills, without first checking out if they have the appropriate management capabilities. Of course, as a first line manager, technical knowledge is very useful. First line managers are probably the ones who need the most technical knowledge of all managers. But a good salesperson does not necessarily make a good manager of other salespeople. So, when deciding on management capabilities, you will be using the level of that post to decide on the importance of technical capabilities versus that of conceptual, visioning and political capabilities. AQAL's 'lines of development can again be used here to suit individuals to different levels of organisation according to their own personal development. References and BibliographyBeck, D.E. and Cowan, C.C. (1996), Spiral Dynamics, Blackwell Publishing. Belbin, R Meredith, (2010), Management Teams, Why they succeed or fail, 3rd edition, Butterworth Heinemann Cacioppe, R. and Edwards, M. (2005), 'Seeking the Holy Grail of organizational development', Leadership and Organization Development Journal, Vol. 25, No. 2, pages 86-105 CIPD (2005), Developing Managers for Business Performance, A Practical Tool from CIPD Research, accessed 28.9.2011 at www.cipd.co.uk/binaries/Tool_06.pdf Cook-Greuter, S. (2003), Postautonomous Ego Development, dissertation available to buy from Harvard University. Cook-Greuter, S. (undated), Ego Development: Nine Levels of Increasing Embrace, [online], http://www.cook-greuter.com/ (accessed 05/07/09) Divine, L. (2009), 'Looking AT and looking AS the client', Journal of Integral Theory and Practice, 4:1, pp. 1-40. Handy, C.B. (1993), Understanding Organizations, 4th edition, Penguin. Harrison, R. (1987), Organization, Culture and Quality of Service, AMED, SOS Free Stock. Esbjorn-Hargens, S. (2009), 'An overview of integral theory', Resource Paper No. 1, Integral Institute, pp 1-24. Hunt, J. (2009), 'Transcending and including our current way of being', Journal of Integral Theory and Practice, 4:1, pp11-20 Kegan, R. (1982), The Evolving Self, Harvard University Press. Morris, T. (2009), 'En Route to Effective Workplace Leadership: An Integral Novice's Exploration', Integral Leadership Review, January Rooke, D. and Torbert, W. (2005), 'Seven Transformations of Leadership', Harvard Business Review Onpoint, April, accessed at http://www.principals.in/uploads/pdf/leadership/7_sevenvtransformations_of_leadership.pdf on 29 October 2013 Torbert, W. (2004), Action Enquiry, San Francisco: Berett-Koehler Publishers.. Torbert, W and Fisher, D. (1992),'Autobiographical awareness as a catalyst for managerial and organizational development' Management Education and Development, Vol 23, No.3, pp184-198 Wilber, K. (2001), A Theory of Everything, Dublin: Gateway.

|