TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

As Wilber stated in " Bodhisattvas are going to have to become politicians", over the years his thinking has inevitably lead to a political theory. As early as Up from Eden (1981), he wrote about "Republicans, Democrats and Mystics", thus looking for a third way compared to the two generally accepted political options in America, which acknowledges the dimensions of depth and psychological growth. In his more recent work, the political dimension is increasingly coming to the fore, see for example The Marriage of Sense and Soul (1998) and the foreword of volume VIII (available at wilber.shambhala.com) of The Collected Works of Ken Wilber. In this essay, Greg Wilpert explores some of the implications of a political theory which takes Wilbers scheme as point of departure. (FV) Dimensions of

Integral Politics

Gregory Wilpert

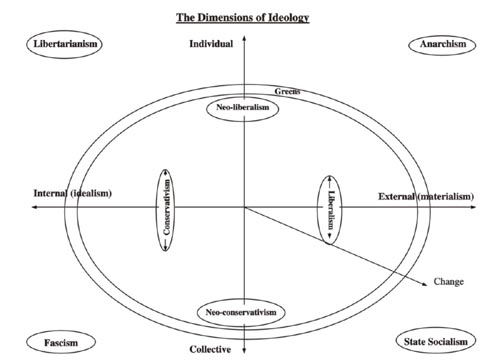

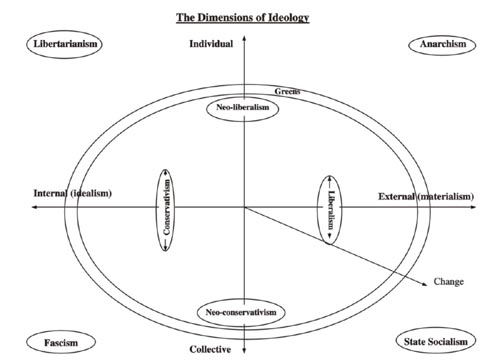

The following is a sketch of how one might map political ideology. On

the basis of this map, I will point to the direction in which integral

politics would lead. This mapping of political ideologies is based on Wilber's

general framework and agrees to a large extent with his political analysis,

particularly as he outlines it in his introduction to Volume 8 of his collected

works. As a matter of fact, Wilber's analysis of ideologies follows a very

similar schema. Still, there are some important differences of emphasis,

which are probably based on my more leftist political commitments. So as

to keep things brief I will assume that readers are familiar with Wilber's

overall theoretical model.(1)

I identify five dimensions of political ideology, in which one can position

all major ideologies. Of course, when making such an analysis, one must

keep in mind that no belief system, no matter how internally consistent,

will fit perfectly within this logical schema. This analysis is merely

intended to give an idea as to how political ideologies relate to each

other and where one might look for an integral politics, one which respects

the truth content in all ideologies, as Wilber would say.

1st Dimension: Causation

The first dimension is one which Wilber calls causation. It is essentially

the dimension that stretches from left hand (internal) to the right hand

(external) in Wilber's overall scheme. That is, some ideologies believe

that internal (or cultural) factors are the primary causes for making society

what it is. This is basically the approach that falls in line with idealist

philosophy, such as Hegel's. I thus call this side of the first dimension's

spectrum idealism. The other side of the causation spectrum is be materialism,

the belief that it is the external or material/observable conditions that

make our society what it is.

2nd Dimension: Unit of analysis

The second dimension is the ideology's unit of analysis and corresponds

with Wilber's upper and lower quadrants, which stretch from individual

to collective. Some ideologies believe that the individual is the more

significant unit of analysis, while other ideologies believe that it is

the collective, which is the more important unit of analysis.

Using just these two dimensions already gives us a two-dimensional map

of how ideologies relate to each other. Roughly speaking, contemporary

liberalism, as found in the Democratic Party, represents a materialist

approach to politics in that contemporary American liberalism generally

believes that social problems can be solved by changing the material conditions

in which these occur. For example, poverty would be resolved through income

redistribution. Conservatism, on the other hand, as represented by the

Republican Party, believes that internal factors or the cultural belief

system cause social problems. Poverty, according to conservatism, would

thus be solved through a better cultural value system. The liberal and

the conservative camps are internally divided along the second dimension

outlined here, in that within liberalism there is a tension between those

who believe the individual is the one whose integrity needs to be maintained

and those who believe that the collective is more important. The same goes

for conservatism.(2)

Extremes

In its extreme forms, the materialist outlook takes the form of socialism

because it argues that all major injustices in our society are caused by

our economic system. As our economic system is a capitalist one, all extreme

materialist perspectives are basically anti-capitalist and are usually

socialist insofar as they do not propose for society to go back to a pre-capitalist

type of economic system. An individual materialist outlook tends towards

anarchism (or anarcho-socialism), in that anarchism (at least in its anti-capitalist

forms) sees the individual as being the primary unit of analysis whose

integrity needs to be respected. Anarchism is thus anti-state as well as

anti-capitalist. An extreme collectivist materialist outlook would be state

socialism because of its anti-capitalist orientation in its materialism

and in favor of collective organization in the form of the state.

The idealist perspective usually, but not always accepts capitalism

as an economic system because it does not see the economy as a system as

being the cause of social problems. It does, however, sometimes see capitalism-the

belief system-as a problem in that the ideology of capitalism promotes

individualism and greed. The extreme collective idealist perspective is

best represented by fascism in its belief that the cultural value system

is what needs to be changed in order to improve society. The collectivist

aspect of this ideology implies that the state or some other organized

form of the collective has a priority in maintaining the cultural order.

An individual idealist outlook would be libertarianism because this ideology

is anti-statist (collectivist) and sees social problems as the result of

an individual's values.

Other ideologies that fit into this two-dimensional model are neo-liberalism

and neo-conservatism. Neo-liberalism represents an attempt to take liberalism

back to its roots in economic liberalism, where the individual is of primary

importance and the material vs. ideal outlook is of secondary importance.

Neo-liberalism is quite pro-capitalist and in its individualist orientation

close to libertarianism, but it is slightly different in that in contrast

to libertarianism tends to see economic success or failure in both idealist

(individual values) and materialist (systemic) terms. Similarly, neo-conservatism

tries to take conservatism to its roots in its emphasis on the collective,

an emphasis that is equally concerned with material and ideal causation.

Many neo-conservative intellectuals were originally Marxists and never

completely lost that part of their analysis that saw the economic system

as a problem. Their switch to conservatism meant placing more emphasis

on cultural (internal) factors than the Marxists did.

3rd Dimension: Form

If we follow Wilber's philosophical outline, we also have to take into

account the level at which any ideological belief system finds itself.

This represents the third dimension of political ideologies. Here we are

basically talking about the level at which we can locate an ideology's

moral and cognitive system. In other words, some ideologies see the world

from the perspective of an egocentric level, others from a membership level,

and yet others from a universalistic level. Nationalistic ideologies, for

example, see the world from the membership level, where the national in-group

is privileged over everyone else. As Wilber points out, liberalism generally

resides on the universalistic or rational level, while much conservatism

tends to be on the membership level.

The Greens/Ecologists

Another important ideology, which I have not mentioned yet, is the belief

system of the green or ecology movement. This movement's ideology defines

itself more on the basis of its cognitive and moral level than on the basis

of its unit of analysis (individual or collectivity) or its analysis of

causation (external or internal). That is, the green/ecology movement tends

to take a holistic view that integrates humanity and nature. This perspective

roughly corresponds with Wilber's centauric or vision-logic stage. The

reason I diagram the green ideology in a circle spanning all four quadrants

is that while all green ideologies have this centauric perspective in common

(or at least try to, although all too often in its flatland version, as

Wilber points out), the individuals who share this perspective come from

all four parts of the diagram. The green movement(3)

is currently very divided between libertarian greens, who support capitalism

and individual liberty, anarcho-greens, who oppose capitalism as well as

the state, eco-socialists, who oppose capitalism but support statist policies,

and the eco-conservatives, who believe that a correct cultural value system

is needed.

I refer to this third dimension of ideology as the "form" of the ideology

in order to contrast it with the fifth dimension of ideology, which is

"content."

4th Dimension: Change

The fourth dimension is change. That is, following Wilber's conception

of the depth and levels of reality, some ideologies argue for progressive

transformative change, others prefer regression, and some no change at

all. Wilber's analysis of our flatland culture figures quite importantly

here because our contemporary culture has practically eliminated any political

ideologies that argue for transformative change. One of the very few ideologies

that supports transformative change is Marxism, in that it argues that

capitalism is merely one stage in the development of society and that anyone

who is concerned with the full development of humanity should fight for

the next stage, which would be Communism according to Marx.

(4)

Thus, the type of change an ideology desires can be, to use Wilber's

terminology, transformative in that it seeks to move society or individuals

from one level of development to another, translative, in that it seeks

to maintain society or individuals at their current level, or regressive,

in that it seeks to move society or individuals to an earlier developmental

level. As stated earlier, practically all contemporary ideologies are translative--"flatland."

A further twist in this dimension of ideologies lies in the proposals

for how change is to come about. This distinction applies primarily to

transformative ideologies, but could also apply to others. Some argue that

change ought to come about via detailed proposals for how to do things

better. This approach has frequently resulted in the criticism that such

planned change will almost inevitably lead towards authoritarian disaster

because one is planning what people should or should not do. This is particularly

the criticism that has traditionally been leveled against Marxism (although

inappropriately, as Marx never laid out what communism should look like)

and Leninism (appropriately because the soviet system did try to force

everyone to accept its vision of the good society). The alternative to

planned change is change via critique. That is, instead of proposing how

things should be done, this perspective argues that it is better to say

how things should not be done or how they are being done poorly. The task

of finding a better way of doing things is supposed to evolve more or less

out of the specific circumstances themselves and are merely guided by critique.(5)

A main representative of the negative or critical approach to social

change is Theodor Adorno (and Jacques Derrida to a certain extent too).

Adorno argues that planned social change (he would refer to it as "positivistic")

ends up in totalitarianism and instead counter-proposes a "negative dialectics"

that finds progressive social change through negation rather than affirmation.

I believe that the negative or critical approach to social change has

a very strong case. I do not think that it is a coincidence that so many

of the prescriptive models did indeed end up in totalitarian social constructions,

despite the best intentions of their founders. I suspect this is also generally

the reason why people find it so easy to accuse Wilber of totalitarian

tendencies (with which I completely disagree with). His system is to a

large degree predicated on the attempt to outline what the higher levels

(at least of consciousness) would look like. In recent times there has

been a backlash against the purely negative or critical approach to social

change, especially now that there are practically no prominent prescriptive

models of how to organize society. The result of all this critique without

vision has been cynicism--a certainty that everything humans have to offer

is somehow flawed, that humans are basically evil, and that there is nothing

anyone can do about it. As a result, I believe it is important to balance

both the negative and affirmative approaches to social change. One might

call this approach "critical positivism" or "critical dialectics".

5th Dimension: Content

This last dimension is not so much a dimension of ideology but an attempt

to highlight that all belief systems have a unique specificity that cannot

be reduced to the previous four dimensions. That is, a belief, an idea,

a perspective, a moral commitment, has aspects to it that are unique and

that one cannot categorize the way the other four dimension's aspects are

categorizable. For example, anti-semitism is a racist or ethno-centric

belief that was part of the Nazi ideology, an ideology one can classify

as having an extreme collectivist analysis, an internal explanation for

causation, and that took the mythic form. However, the fact that this ideology

identified Jews as its particular target is the result of a unique historical

constellation and has nothing to do with the ideology's location in this

scheme. I am inclined to say that the content of political ideologies is

just as important as its formal structure when we are trying to make sense

of the role ideologies play in our politics. (6)

Integral Politics

Ultimately, an integral politics that follows in Wilber's footsteps

is a politics that takes each of the dimensions (or as Wilber phrases it,

quadrants and levels) seriously. This means in practical terms a recognition,

first, that causation is both internal and external: both our cultural

value system and our social institutions equally shape our condition. Second,

that our analysis needs to honor both the collective and the individual:

human life is not possible without the collective nor without the autonomous

individual. And third, that fulfilling our human potential means exhausting

each level of development and then moving on to the next. Clearly, this

outline is much too general for a practical political program. One cannot

develop practical politics out of logical abstractions, but only in relation

to a concrete social and historical analysis. But that is the topic for

another paper (or book).

Endnotes

1. Of particular relevance here are Wilber's Sex,

Ecology, Spirituality; A Brief History of Everything; and Marriage

of Sense and Soul.

2. This two-dimensional model is basically the same

as the one Wilber outlines in his Introduction to Volume 8 of his Collected

Works. Another theorist who has the same model is Lawrence Chickering (1993)

in his Beyond Left and Right.

3. Having grown up in Germany, I am actually much

more familiar with the German green movement than with its US counterpart.

So what I say here might not quite apply to the US. Still, considering

that the German green movement is one of the strongest in the world, it

is legitimate to use this movement as an example of green ideology.

4. By Communism Marx did not have in mind state socialism

as it was implemented in the Soviet Union. Instead, he believed a Communist

society to be a society in which "the full development of each is a condition

for the full development of all," and where all of society's benefits would

flow "to each according to his needs and from each according to his ability."

I am in substantial disagreement with Wilber's

interpretation of Marx. Well, to be fair, Wilber says he is talking about

Marxism and not Marx. But Wilber's readers, who know about Marx only through

what he writes, will get a view that has been distorted by "vulgar" Marxism.

Wilber says that Marx was only concerned with the material realm and reduced

all human activity and productivity to this realm. In other words, according

to Wilber, Marx was merely concerned with the physio-sphere. This is true

to an extent, in the sense that people need to eat before they can philosophize.

But Marx' primary concern was with finding higher forms of social organization

through the critique of the capitalist economy and the blockages in evolution

that it creates at the level of the physio-sphere.

5. I would like to note here that there is fundamental

parallel between social critique and meditation. Both techniques are meant

to deconstruct, preserve, and raise to a new level ("Aufhebung" is what

Hegel called this). The difference between the two is that while meditation

is for individuals, social critique is for society. The basic principle

is similar so that one can call social critique a form of social meditation.

6. I think that Wilber's entire system too easily

leads to an analysis where the formal structural qualities take precedence

over the unique and historical. In other words, that form takes precedence

over content, even though one is not possible without the other.

|