TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020). Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020). Outgrowing the

|

| YESTERDAY | TODAY | TOMORROW |

|---|---|---|

| Mythic | Rational | Mystic |

| Literal | Anti-Literal | Metaphoric |

| God Everywhere | God Nowhere | God Everywhere |

| Theism | Atheism | Somethingism[4] |

| Creationism | Evolutionism | Integralism |

This developmental scheme allows us to frame various authors who speak out for or against religion in our times. The New Atheists belong to the middle phase of secular rationality. In some cases, such as Richard Dawkins, a strong negative stance towards religion is advocated—as one of his book titles clearly says: The God Delusion (2006). Pro-religion responses have argued Dawkins is attacking not religion as such but merely an outdated form of fundamentalist religion, not the more liberal and even mystical forms. To which he might counter: that out-dated form of religion is still very much and often dangerously present in the world of today—an analysis Wilber would share[5]—so urgently needs to be addressed, if not attacked.

In Integral Spirituality (2007) Wilber introduced the concept of the "level/line fallacy", which is helpful here. If the whole line of religious development is reduced to only one of its stages (the mythic-literal stage) or levels, then both those for and against (this type of) religion have an impoverished view of the field as a whole. Fundamentalists and atheists both agree on the same narrow definition of religion. When they get into a (hopeless) argument, they lock eachother up in a tight embrace.

Many integralists would agree with Dawkins that mythic-literal religion is something of the past, which we need to outgrow, but that other forms of spirituality might be on the horizon, or even already among us now (mindfulness anyone?), which include the advances of science and evolution instead of denying them. So why stop development at the middle, anti-religious phase? Perhaps we can move on to new vistas and futures? Dawkins has not been impressed by critics who argue his theology is not really up to date. In his opinion, no amount of sophistication will save religion, because it promotes belief without evidence.

In Wilber's psychoanalysis, these New Atheists suffer from a "heaven allergy" a denial of Spirit, when they vehemently attack any form of religion.

"The Four Horsemen"

* The New Atheists are Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, Christopher Hitchens and Sam Harris. Not Stephen Hawking. Together they are nicknamed "The Four Horsemen" (FV).

Ironically—and now that we are psychologizing—when it comes to "cherry picking" and "sheer vehemence", Ken Wilber has abundantly shown his allergy towards neo-Darwinism—should we call it "rabid" too, including the "frothing at the mouth"? He has called the standard neo-Darwinian theory "moronic"[6], and exclaimed recently: "the modern theory of evolution is catastrophically incomplete!"[7] How hard is it, really, to repeat a few creationist platitudes to downplay the accomplishments of evolutionary science, without engaging that widely diverse field? What "projected shadow material" is driving Wilber here actually? His fear of a meaningless universe? There clearly is boiling something under the surface here, that needs to be exposed and clarified, before we can have any reasonable discussion. Dead giveaway!

So, I would ask, if the mythic God has failed, why would the mystic God Wilber proposes fare any better? Does Wilber provide new evidence, based on his mystical experiences and/or his readings of other mystics? Has he really included evolutionary science into his integral metatheory, or, as I have extensively argued, misrepresented its basic tenets? How solid is "evidence" of that type? Can we say anything with confidence about reality based on experiences that are by definition ineffable?

GOODBYE GOD

In his recent book Outgrowing God: A Beginners Guide (2019) Richard Dawkins returns to the topics of God and evolution which he has covered in previous works, but in a language that should appeal to the younger generations.[8] The book is divided in two parts: "Goodbye God" and "Evolution and Beyond". We wil leave Dawkins' dealings with orthodox religion for what it is. (And yes, Noah comes along, and the interesting story of how two thousand years before that story was written tales of a flood and an ark already existed—there was the Babylonian legend of Utnapishtim, which in turn comes from the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh—everything is there, including the rainbow and God's promise never to do this again.)

Regarding the existence or non-existence of God, Dawkins repeats his favorite argument that, given the large number of gods in the various religions, what makes you think that your own god exists and all others don't? Why not take the small extra step and deny existence to your own god as well? Are not all theists atheists when it comes to other gods? Is there any reason to think you were born in a religion that happened to worship an existing God?

For him all of the Old and New Testament is a mix of history, legend and mythology, created by the unreliable oral traditions that passed on these stories. But he concludes on a positive note:

So we've dealt with the Bible as history. It mostly isn't. And we've dealt with the Bible as myth. Much of it is, and there's nothing wrong with that. Myths are rightly valued. But there's nothing to single out the biblical myths as any more valuable than the myths of [other religions]" (p. 70)

Hardly the rabid anti-spirituality you would expect from him following Wilber's advice!

Discussing the Old Testament as a source of morality, Dawkins tells the numerous stories of etnic cleansing, human sacrifice and sexual abuse. Be it the story of Noah's Ark, the ordeals and sufferings of Job, Abraham's sacrifice of Isaac, and many others, they tell us of a jealous God, who is hardly an ethical role model ("The Lord is a jealous and avenging God"). Dawkins even draws parallels between the Promised Land story and Hitler's demand for Lebensraum. If that sounds horrible, it is: "When you cross the Jordan into Canaan, drive out all the inhabitants of the land before you." (Numbers 33:52) These divine commandments echo until our own times in the religiously inspired claims to occupy land in the Middle East.

Taking into account that most of Christian theology was furnished by St Paul, who preached the doctrine of Original Sin and the consequent need of an atonement, Dawkins exposes with obvious delight the illogical and repulsive idea of a God unable to forgive his people without torturing and killing his only Son (being Himself at the same time!). He comments: "The doctrine of atonement, which Christians take very seriously indeed, is so deeply, deeply nasty that it deserves to be savagely ridiculed." (p. 89). So no metaphorical or mystical re-interpretation here….

Even more illuminating, Dawkins points to the curious role played by Judas, the disciple who betrayed Jesus, and is considered by most Christians to be the villain of the piece. But wasn't the whole point of the divine scenario that Jesus had to die, in order to suffer for our sins? But no, for centuries the Jews have been blamed for "killing Jesus", by many Christians from Luther to Hitler, as if that wasn't exactly what God had demanded—resulting in ages and ages of anti-Semitism and all its horrors until this very day.

And if you think the New Testament does any better in providing us ethical guidelines, he says, think twice:

So, although the Old Testament is richer in sheer numbers of horror stories than the New, you could say that the central message of the New Testament [the atonement] is a strong contender for the grim distinction of being the most horrific of all. (p. 89-90)

Delusions, indeed. And very harmful at that.

Clearly we don't need a God to be good, according to Dawkins—least of all the jealous and vengeful God of the Bible. The Ten Commandments supposedly give us ethical guidelines for our current world, but when commenting on them one by one, Dawkins is less than impressed. The most important one, "Thou shalt not kill", he considers to be "almost too obvious". Funny that Jehovah did not see any problem in killing people of other tribes. For all Christian nations, in situations of war, these ethical rules can be relaxed, even if two Christian nations are at war with eachother!

This is the God we need to outgrow, Dawkins concludes at the end of Part One. Especially because the times have changed, and we now think differently about a whole lot of ethical questions. We no longer allow for stoning, or slavery, or killing civilians in wartime. We have moved on. Perhaps we have progressed morally. We now have our own morality, and science, our conscience and common sense.

Is Dawkins making it himself too easy by focusing on the mythic God of the past? Are there other options? Do his views have implications for the proposed mystic God/Spirit of the future? Shouldn't he, in other words, outgrow his atheism? Has he ever meditated?[9] My feeling is that he doesn't feel the need to explore these dimensions. Nature and science are for him an endless source of wonder. It would, indeed, be wonderful if more and more people in this world are able to embrace this science-based rationalistic and humanistic worldview. "The Religion of Today".

To summarize, for Dawkins, all religion is myth, and he adds, that's fine as far as it goes, but it can't compete with science as to its truth claims. For Wilber, mythical religion is just one among many, one step of a whole ladder, and the post-rational, mystical forms of religion have truth claims of their own, that surpass both those of myth and science. That is a huge knowledge claim.

As a teaser for Part Two (on "Evolution and Beyond") Dawkins adds:

But you might still cling to belief in some kind of higher power, some sort of creative intelligence who made the world and the universe and—perhaps above all—made living creatures, including us. (p. 141)

EVOLUTION AND BEYOND

Indeed, it is the very complexity of nature that is often used by religious thinkers (both from the mythical and the mystical variety) to argue for the existence of precisely such a "creative intelligence", "some kind of higher power"—Ken Wilber included. Again and again Wilber has used examples from biology to claim the failure of science to explain their complexities. And consequently, to argue that there is a real need to postulate an "Eros-in-the-Kosmos", which produces matter and consciousness.

Integral students are making it too easy for themselves to say: "we no longer believe in such a mythic God, so Dawkins should educate himself about spirituality and development." They also need to confront Wilber's claim of superior knowledge.

Make no mistake, Wilber has often aligned with creationists to argue against neo-Darwinism, and in favor (against these very creationists) of a mystical, Spirit-driven view of evolution. As he has often said, these creationists (or Intelligent Designers) are correct about the failures of science to explain complexity, even though he disagrees with them, quite strongly in fact, about their proposed solution (i.e. the mythic God of creation).

He has not taken the trouble to investigate if evolutionary science itself has perhaps moved on beyond the confines of Darwin (and Dawkins)—such as in the field of evo-devo. Nor to what extent the Darwin-Dawkins paradigm is perfectly capable of explaining adaptations. Creationists typically allow for certain variations, but up to a certain taxonomic level. Wilber is no exception, though he never gets specific. And only by getting specific can we have an intelligent conversation about this.

It's like there is a kind of Spirit-Matter slider, and all evolutionary authors set it differently. Theists will set it closer to the Spirit-end, and materialists will set it to the opposite end. But even theists allow from some random variation, in which Spirit is not involved. And even materialists allow for processes other than random chance.

No, Wilber means mystical business when he exclaims: "the modern theory of evolution is catastrophically incomplete!" And in The Religion of Tomorrow he claims, even more pretentious, to have a theory of evolution that is superior to that of science:

And in the same volume he explicitly states that, in his understanding, evolution itself is evidence for Spirit:

As I have pointed out in other essays, Wilber doesn't understand the paradox that evolution can happen even given the Second Law, and that evolution is not only a matter of "chance mutation", but also of selection and a lot of other mechanisms recognized by science as well. And that "evolution" in the physical domain is governed by other than biological forces, such as cooling and gravity. To make up for this, he sees it all as driven by a generic, unspecified drive of Eros.

Note also the happy-go-lucky style of argument, so typical of Wilber, "this can easily be seen as yet more evidence of creative Eros or Spirit-in-action"... Easily? Really?

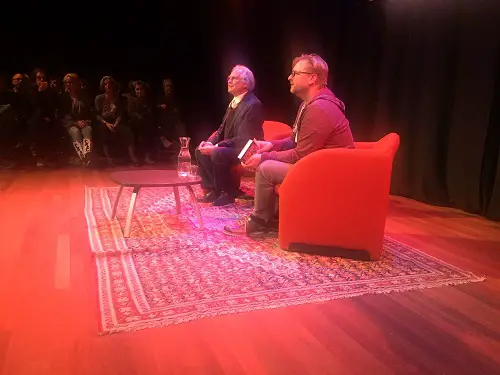

Dawkins, of course, disagrees with all these sentiments. He is the true champion of extolling the virtues of the Darwinian explanation of biological complexity. As he recently said during the book presentation of Outgrowing God in The Hague, which I attended: "Charles Darwins idea of natural selection is ridiculously simple and ridiculously powerful. It explains the complexity and the diversity of life."

The second half of Outgrowing God is a superb defense of the Darwinian approach to evolution, against all those "Somethingists" who want to retain some form of God.

A chameleon catches a fly with his elastic tongue.

What always strikes me when reading Wilber is his complete lack of interest in how nature actually works. The only reason he mentions biological topics (eyes, wings) in his works is to support his spiritual view of evolution. He could not care less about how camera eyes or birds wings have actually evolved over millions of years. The difference between Dawkins and Wilber couldn't be starker. Dawkins spends five pages on how the long and flexible tongue of a chameleon is able to catch an insect! This love for detail and respect for the wonders of nature Wilber simply lacks. And the consequences are huge. For he resorts to abstract and mystical speculations about evolution that lack any scientific validity.

To impress the reader with the enormity of the challenge for science to explain nature's complexities, Dawkins proceeds with giving examples as diverse as the camouflage behavior of the octopus, the human eye, the human brain, the Hemoglobin molecules in your blood, metabolic processes happening in a single cell, etc. It's done on purpose:

Awe-inspiring complexity. Once again, it seems to demand a master designer. And once again, later chapters will show that it doesn't. That's quite a challenge; and the purpose of this chapter, to repeat it, is to show how big the challenge is. Before we step up to answer it. (p. 163)

Read "Eros" or "Spirit" for "master designer" and he's talking to Wilber. And Wilber—like all creationists—extols the complexities of nature as evidence for some kind of Spirit, a self-organizing or self-transcending drive. These terms are vague enough to allow for both a materialistic and a spiritual interpretation.

Creationists like to play the complexity-card. Science tries at least to meet the challenge of explaining this complexity. "Every so unsuccessfully" boasts Wilber. That remains to be seen and can only be concluded after carefully investigating the field.

Now Wilber would say: "but surely there has to be some sort of Spirit behind it all? It can't all be the result of blind chance!" He should carefully listen to Dawkins:

It's completely obvious that animals and plants don't come about by random chance.… Whatever is the true explanation for all the millions of animals and plants, it can't be luck. We can all agree about that. So, what's the alternative?

Unfortunately, at this point many people go straight down the wrong path. They think the only alternative to random luck is a designer. If that is what you think, you're in good company. It's what almost everybody thought until Charles Darwin came along in the middle of the nineteenth century. But it's wrong, wrong, wrong. It isn't just a wrong alternative: it's no alternative at all. (p. 174)

And why not? Explaining complexity by design requires an explanation for the Designer. Or Spirit. Which can by definition not be given. Is it therefore not true? No, but it is not a good scientific theory. Because it is a top-down solution.

Through example by example Dawkins proceeds to demonstrate, that evolution can work itself from the bottom up, taking "steps towards improbability", evolving functionality, by tiny changes (gene mutations). And as long as favorable mutations are passed on to the next generations, evolution can proceed, without any guidance or plan.

And he clarifies the level at which things are really happening:

Evolution consists of changes in the proportions of genes in populations. What we see from outside is changes in bodies and behaviour as the generations go by. But what is really going on is that some genes are becoming more numerous in the populations and others less numerous. Genes survive, or fail to survive, in the population as a direct result of their effects on bodies and behaviour, only some of which are visible to us. (p. 184)

A lot is accomplished in nature by self-organization, or as Dawkins calls it: "self-assembly". Now these are terms that are easily misinterpreted, as has been done by Wilber. He has co-opted these terms and linked it to a spiritual metaphysics, as if there is a spiritual drive towards self-organization in the cosmos at large, and in the biological domain in particular. But the opposite is in fact true: self-organization happens, not by being "driven" (then it wouldn't be self-organization anymore, would it?) but all "by itself". These processes can be understood and are non-mysterious.

TAKING COURAGE FROM SCIENCE

— Richard Dawkins

Dawkins closes the book by two chapters, one on the question if being social and religious has evolutionary roots (the answer is yes), and one on how we move from here into the wider field of cosmological science. If God is no longer needed to explain the complexity and diversity of nature, does the same apply to the cosmos? Again, many cultures thought the cosmos has a divine origin ("for, how else…"), but we should again think twice. One thing we have learned from Dawkins: if God is proposed as explanation for the cosmos, then God itself requires an explanation. Which is never forthcoming.…

Hence atheism. And it was Darwin who gave us the confidence that science can tackle seemingly insurmountable problems, such as the origin of species, in a non-question begging way. In the final chaper "Taking Courage from Science", Dawkins reminds us how counter-intuitive scientific discoveries often have been (and are) and how they have been met with incredulity ("You can't be serious!", he quotes John McEnroe) before they finally got accepted.

Here are some of them[10]:

- A heavy and a light object will hit the ground at the same time, when dropped from a height.

- The moon is weightless and continuously falls down towards the earth.

- The earth moves around the sun, at high velocity, instead of being at the center of the universe.

- The continents actually have moved, and still move around the surface of the earth.

- You and the chair you sit on consist mostly of empty space.

- Not a single atom in your body was there when you where a child.

This is Dawkins' final message:

Science regularly upsets common sense, and can even be frightening. We need courage to face up to it.

And far more often than it is bewildering or frightening, scientific truth is wonderful, beautiful. You need courage to face the frightening, bewildering conclusions of science; and with the courage comes the opportunity to experience all that wonder and beauty. The courage cut yourself adrift from comforting, tame, apparent certainties and embrace the wild truth. (p. 263)

Some scientific ideas even he finds scary. Or too early to tell if they are true:

- When you travel with the speed of light, you would not grow old.

- Some quantum events happen only when you take a look at them.

- In the Many Worlds hypothesis, there are trillions of alternative worlds.

- Our universe might be part of a much larger Multiverse of universes.

- There was a time the universe was small beyond all contemplation.

- The fundamental constants of physics seem fine-tuned for life to arise.

Some of these theories might lend new evidence for the idea that there's a divine presence behind it all, but predictably Dawkins concludes, to always resist such a "transcendental tempation":

It's a tempation that should be sternly resisted.… Importing a god into the reasoning doesn't solve the problem. It simply pushes it one stage back. It is a crashingly obvious non-explanation. (p. 272-273)

Isn't science wonderful? If you think you have found a gap in our understanding, which you hope might be filled by God, my advice is: "Look back through history and never bet against science." (p. 275)

NOTES

[1] Ken Wilber, The Religion of Tomorrow: A Vision for the Future of the Great Traditions - More Inclusive, More Comprehensive, More Complete, Boulder, Shambhala, 2017.

[2] Richard A. Hunt. (1972) "Mythological-symbolic religious commitment: The LAM scales", Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 11(1), 42-52.

[3] Andrew M. Greeley, "Comment on Hunt's "Mythological-Symbolic Religious Commitment: The LAM Scales", Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, Vol. 11, No. 3 (Sep., 1972), pp. 287-289.

[4] A term coined by the Dutch atheist political columnist and molecular biologist Ronald Plasterk. Plasterk has come to appreciate the difference between this vague spirituality and militant fundamentalism. The Dutch term is "ietsisme". There is not yet an English Wikipedia page for it, but Wiktionary.org calls it "Somethingism: an unspecified belief in some higher force." and "Ietsism: an unspecified belief in an undetermined transcendent force." That would match perfectly with Wilbers "Eros-in-the-Kosmos", an unspecified cosmic drive towards complexity and consciousness.

[5] In The Religion of Tomorrow he estimates that 60 to 70 percent of the population is at the ethnocentric, mythic-literal stage of development (p. 321).

[6] Ken Wilber, The Religion of Tomorrow, Shambhala, 2017, p. 219. See also: David Lane, "Ken Wilber and 'Moronic' Evolution: The Religion of Tomorrow and the misunderstanding of Emergence", www.integralworld.net, 2017.

[7] Ken Wilber and Corey De Vos, "Kosmos: An Integral Voyage", www.integrallife.com, July 16, 2019. See also my initial response: Frank Visser, "Does Every Outside Have an Inside?, Ken Wilber's Strained Relationship to Science", www.integralworld.net, July 2019.

[8] Richard Dawkins, Outgrowing God: A Beginners Guide, Bantam Press, 2019.

[9] Actually he has. In a recent podcast "Making Sense" (#174) with Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris tried to seduce Dawkins to try some mediation exercises. It didn't work out. As Dawkins said afterwards, he "didn't see the point of it." Nov. 4, 2019.

[10] These discoveries all belong to the external world. Wilber would add the following "interior discoveries" belonging to an "internal universe":

- Consciousness goes all the way down, to the level of atoms (pan-interiorism).

- The mind-body problem can only be resolved in non-dual contemplation.

- Enlightenment is the ability to stay conscious even in deep dreamless sleep.

- It is possible to stop all the known brain waves in deep meditation (video).

- In our deepest being we are one with, and even identical to the Supreme Mind.

- Evolution from atoms to humans is driven by a self-transending "Spirit-in-action".

Are these interior hypotheses also waiting to be confirmed? Dawkins has a word of caution here, and a challenge:

A word of caution, by the way, before we go on. Galileo, Darwin and Wegener proposed daringly surprising ideas and they were right. Plenty of people propose daringly surprising ideas and are wrong, crazy wrong. Courage isn't enough. You have to go on and prove your idea right. (p. 269)