|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020). Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020). Looking For

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| LEVELS | REALMS |

|---|---|

| 12. Geopolitical states | MIND/CULTURE |

| 11. Agrovillages | |

| 10. Tribal metagroups | |

| 9. Animal social groups | LIFE |

| 8. Complex multicellular organisms | |

| 7. Eukaryotic cells | |

| 6. Prokaryotic cells | |

| 5. Molecules | MATTER |

| 4. Atoms | |

| 3. Atomic nuclei | |

| 2. Nucleons: protons and neutrons | |

| 1. Fundamental quanta |

In Wilber's understanding, this model shows a conflation of individual (levels 1-8) and social entities (levels 9-12). Where atoms, molecules, cells are distinct entities with clear boundaries, animal and human groups are of a different order. As Volk admits, the boundaries of animal groups are more "fuzzy" than those of individual organisms (p. 121-122). He almost sounds disappointed that complex beings cannot physically merge... (he mentions insects such as ants as an example of this evolutionary impossibility—but also points to certain marine animals which seem to have found ways to do exactly that). This "conflation", however, is easily remedied if we move the upper levels of Volk's model to the "social" column and fill in the empty cells with corresponding values (in bold type):

| INDIVDUAL HOLON | SOCIAL HOLON |

|---|---|

| 12. State-citizen | 12. Geopolitical state |

| 11. Farmer | 11. Agrovillage |

| 10. Hunter and gatherer | 10. Tribal metagroup |

| 9. Animal | 9. Animal social group |

| 8. Complex multicellular organism | 8. Group of complex multicellular organisms |

| 7. Eukaryotic cell | 7. Group of eukaryotic cells |

| 6. Prokaryotic cell | 6. Group of prokaryotic cells |

| 5. Molecule | 5. Group of molecules |

| 4. Atom | 4. Group of atoms |

| 3. Atomic nucleus | 3. Group of atomic nuclei |

| 2. Nucleon: protons/neutron | 2. Group of nucleons |

| 1. Fundamental quantum | 1. Group of fundamental quanta |

What is more, Wilber is aware of the ultimate arbitrariness of the distinction between individual and social:

When atoms combine into molecules, creating new relations and realities in the process, and individual organisms combine into groups and societies—what's the essential difference? Wilber objects to the notion that collectives and societies, or biospheric Gaia, are somehow "higher stages" we "ultimately belong to". According to Wilber, where atoms are parts of molecules, human beings are members of society.

That aside, the distinction between individual development and its social expressions seems illuminating. It doesn't seem to invalidate Volk's model if we slightly reclassify its levels into individual and social levels—though it would interrupt his neat combinatory logic. But more evolved social groups require more evolved group members—so they evolve together.

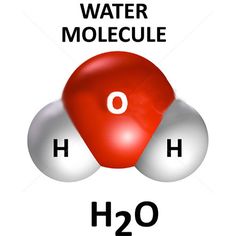

Case Study: The humble water molecule

Where Volk's approach is markedly different from Wilber's is in the description of the way we navigate and move upward through the various levels. Let's take the simplest of examples, used by both Wilber and Volk: the emergence of the water molecule H2O. When two Hydrogen atoms and one Oxygen atom combine into one water molecule, resulting in a new entity with features not seen in its constituting components, Wilber describes this remarkable transformation as follows (in the context of his Twenty Tenets of evolution, under the item "self-transcendence"):

In typical Wilberian fashion, this elementary chemical process is rephrased in an almost mystical-theological frame of reference. Volk, not unexpectedly, takes a more mundane—but therefore more illuminating—approach:

We might pause here on humble H2O, the water molecule. It looks something like a round head (the oxygen atom) with two round ears (the hydrogen atoms) sticking up at two o'clock and ten o'clock, like a simple cartoon. It is polar. Each hydrogen atom's single electron is tugged towards a powerful electron grabber, the oxygen atom, which, when solo, lacks two electrons in its own mandala. Thus, in the overall system of the polar H2O molecule, the two hydrogen ears are positively charged relative to the more negatively concentrated oxygen head.

This polarity gives the potential for weak bonds among water molecules. The hydrogen side of one molecule gets weakly linked to the oxygen side of other water molecules. These so-called hydrogen bonds among water molecules are like ribbons that form and break. Because the hydrogen bonds are weak compared to the tethering of electrons to nuclei in the atoms themselves, the hydrogen bonds play a crucial role: they make water, well, slippery, wet, watery. (p. 64)

Where in Wilber's "explanation" the existence of water seems almost miraculous, requiring a spiritual intervention, in Volk's analysis, the origin of water molecules becomes not only understandable but inevitable. The water molecule has filled its electron shells and has reached a preferred energy-state. Volk uses the phrase "energy repose" (p. 35). The biggest mystery in the Grand Sequence of events seems to be how individualities form collectives, which in turn become individualities in their own right. By allocating collectives to a separate stream of development, Wilber loses the opportunity to clarify these transformations—and he has to resort to mysteries. Indeed, Volk's concept of "combination" might well be a key insight here.

This difference in flavor and substance of these two approaches is exemplary for how spiritual philosopher Wilber and scientist Volk approach the subject. Even though Wilber quotes extensively from scientific sources in the first few chapters of his Sex, Ecology, Spirituality, he puts a spiritual and abstract spin on these scientific findings which make the realities of the various domains of matter, life and mind/culture disappear below the horizon.

COMBOGENESIS AS CROSS-DOMAIN PRINCIPLE

Both authors try to formulate cross-domain principles that hold true across the domains of matter, life and mind/culture. The problem here is to find concepts that are not merely descriptive, such as "emergence", "transcend-and-include", "transformation", but that really clarify something. While it may be true to say that molecules "transcend-and-include" atoms—Wilber's mantra—it doesn't really help us understand how molecules have come to be in the first place. Through a process of transcendence? Emergence? Transformation? This is clearly insufficient to count as scientific explanations. Volk's suggestion is: combogenesis.

So I use the following word: combogenesis. The idea is genesis by combination. The word riffs off the informal term for a small, cooperative jazz group, combo. Why coin the term? Quite simply, I haven't found any current word for the concept I want to discuss.

Combogenesis is the genesis of new types of things by combination and integration of previously existing things. (p. 13)

Tyler Volk

Combogenesis not only creates new entities such as molecules, cells and societies, it also makes available new relations. This is were Volk's treatment excels, in my opinion. What relations are possible for molecules (such as the water molecule mentioned above) that weren't possible for its atomic elements? How do protons and neutrons behave differently from their quark components? How, for that matter, did multicellularity arise from single-celled organisms and what was the payoff of that process? What exactly did agriculture bring to human beings that simple hunting and gathering couldn't provide? What did life introduce in the universe that matter lacked? And what, finally, did culture make possible, that isn't available to less complex animals and physical matter?

The controversy about what drives evolution (at least in the biological sense) is often phrased as "competition versus cooperation". Now we have a third option: combination. Where competition and cooperation are often emotionally charged (and often framed as male versus female), combination is a more neutral term that seems to have a very wide application.

Another intriguing aspect of Volk's model, is his clarification and classification of what has been called the "three big bangs": the atomic, genetic and linguistic explosion that caused the emergence of matter, life and mind/culture in all their myriad forms and variations.[8] Again, theologically or spiritually oriented philosophers would see in this (threefold) explosion of creativity the hand of some higher Being—however abstractly visualized—but a more scientific mind would choose a more mundane explanation. Just as uncountable words can be made by a limited set of letters (think: alphabet), and millions of species evolved due to less than a handful of DNA base pair combinations, so the entire Periodic System of the Elements can be generated using only a few elements: protons (P), neutrons (N) and electrons. Volk coins this cross-domain pattern the "alphakit".

This can be visualized as follows, showing clearly what a mere combination of elements can accomplish (the diagram is not from the book):

| ELEMENTS | COMBINATIONS |

|---|---|

| LINGUISTIC (LETTERS) | T-H-I-S-I-S-A-S-E-N-T-E-N-C-E |

| GENETIC (BASE PAIRS) | A-T-A-C-G-A-C-T-G-G-A-T-T-C |

| ATOMIC (NUCLEONS) | P-N-P-N-N-P-P-N-N-P-P-P-N |

Given his combinatory logic, it is understandable that Volk switches from individual to social dimensions, at a given point in his model. For when the level of complex multicellular organisms is reached—at two-thirds of the Grand Sequence—there's nothing these organisms can combine with, except with similar organisms. Until then, the logic seems to hold firmly. Quarks combine into nucleons, nucleons combine into atomic nuclei, atomic nuclei combine into atoms, atoms combine into molecules, molecules combine into prokaryotic cells, prokaryotic cells combine into eukaryotic cells, eukaryotic cells combine into complex multicellular organisms.

Literally. Not poetically. Not metaphorically. Not as a matter of speech. Not to suggest a mysterious process in the background. Or to hint at the extraordinary complexities of Nature—the standard ways in which Ken Wilber usually argues his point. Volk offers a strong antidote to the essentially anti-scientific sentiments frequently voiced by Ken Wilber.

Here's a good example of the type of rhetoric Ken Wilber is so fond of:

Now, it's really astonishing that universe would do this. Some think that this is some sort of chance, random mutation, but that, in fact, is exactly what it isn't. It's the opposite of chance or randomness.

It's evidence of a force that is pushing against randomness in the universe.

Now, Neo-Darwinian evolutionary theory holds that all these transformations upward were just the result of chance and randomness. But there is no way in hell that the universe went from atoms to Shakespeare [or from quarks to culture] out of random stabs. This is an extraordinarily driven process. (EnlightenNext, 2011, Issue 47.)[9]

Ken Wilber is correct that the stupendous transition from quarks to culture is not a random walk, and that "something else" is driving it, but that "something else" can be explored along religious or along scientific lines. Regarding this question of what actually drives evolution onwards and upwards in all domains, Wilber takes the religious route where Volk offers believable alternatives, that are more grounded in science. For Wilber, every next step in the Grand Sequence is almost a miracle. These feelings are fine, and even Volk has them, but they shouldn't predominate and replace the efforts to find explanations. But Wilber doesn't even try to understand these processes in more detail. Volk does make these same steps, if not inevitable, than at least plausible, and presents them as the result of purely naturalistic mechanisms.

For example, in the domain of physics, it is cosmic cooling and gravity that allow the levels of material complexity and relations to build as a sequence from quarks to atoms. Because of cosmic cooling quanta became nucleons, nucleons became nuclei and nuclei with electrons became the first simple atoms. At a much later time in cosmic history, most of the more complex atomic nuclei were (and are being) forged in the interior of exploding stars—again, environments that facilitate the natural combinatorial potentials of the nucleons on the prior level. (Those complex atoms get their electrons—what Volk calls “exit prizes” (p 51)—as they leave the stars to enter the swirling gases and even planets of the universe.)

In contrast, at the chemical level the much weaker electromagnetic forces take over: atoms with their electrons shells of various sizes find ways to connect, which would be unthinkable in the earliest universe or it's hottest sites. In the biological domain of living organisms, endosymbiosis and cell division are the crucial mechanisms that open the windows to greater complexity. Cell division might actually have started multicellularity by not completing its process, so that cells sticked together. Endosymbiosis was the great and unique event of a merger of two types of bacteria, with one (archaea) becoming the host for the other (bacterium), resulting in organisms that could grow enormously in size and complexity, whereas bacteria alone kept running into unassailable limitations—as they still are today.

At no point does any miraculous or transcendental step occur. This undercuts a major thesis of Wilber's cosmology. For Wilber, every step in the hierarchy is unexpected. For him, each of these transformations can ultimately only be explained by invoking some transcendent/immanent external/internal force (Eros). Volk represents the opposite end of the spectrum: each step has a certain logic and empirical plausibility.[10]

The fine granularity of Volk's levels is evenly distributed between the domains of material/physical, chemical/biological and mental/cultural. These three basic divisions Volk calls "dynamic realms". These are, of course, the realms of matter, life and mind:

The twelve levels form a set of similar phenomena that can be used to seek additional findings. Within the grand sequence, there are three largest-scale, natural families of adjacent levels, designated the dynamical realms: the realm of physical laws, the realm of biological evolution, and the realm of cultural evolution. Common themes shared by the levels within each realm are related to a realm's core dynamics. Within the grand sequence the dynamical realms imply another theme: each realm had a first level, its base level, which can serve to focus further analysis. (p 149)

| REALMS | LEVELS | |

|---|---|---|

| CULTURAL EVOLUTION | LEVELS 10-12 | |

| BIOLOGICAL EVOLUTION | LEVELS 6-9 | |

| PHYSICAL LAW | LEVELS 1-5 | |

From the base levels of each domain, all of its phenomena came about from the overarching dynamics born at its base level (as well as from local dynamics specific to each level). The fundamental quanta established physics and chemistry, the dynamics for the next 4 levels. Prokaryotic cells established biological evolution, the dynamics for the next 3 levels. Tribal metagroups established cultural phenomena, the dynamics for the next 2 levels (so far, but see below).

Playfully switching between the dynamical realms and their levels, Volk notes common themes that illuminate fundamental processes. According to Volk, for example, Darwinian principles of "propagation, variation and selection" are explicitly at work in the two “evolutionary” realms[11] and what cultural evolution adds as special to that common theme is a “dual-tier” PVS in society and the mind. Common themes across realms stand out as well: the origin of eukaryotic cells, combining two different kinds of prokaryota (bacteria and archaea) is paralleled in the origin of agrovillages, where plants and animals are domesticated and integrated into one unity. Both overcame important energy constraints for further growth towards complexity: once the eukaryotic cell was established, complex biological life took off. And once the agrovillages were established, food production and population growth increased dramatically. Their previous stages (prokaryotes and hunter-gatherers) were somehow not able to grab these opportunities.

Speculating about our future Volk suggests we might be on our way to a next level (or even a next dynamical realm?) when we transcend the level of the geopolitical states, and arrive at a situation of "stable relations of nations within the new larger thing" (p. 195). Will "globalization, the Internet and instant news cycle" we are witnessing today usher in the noosphere, Volk asks (with a reference to Teilhard de Chardin)? But his answer is sober: "Given these considerations, we don't seem to be at the new level yet." (p. 198). What will happen to the individual, within these ever-growing spheres of collective life? Will AI get integrated into human life, like the endosymbiosis of the eukaryotes of the past? Are we in the Anthropocene, where we have "humanized" the biosphere beyond any doubt? A planetary world-culture might be "the final level of the realm of cultural evolution" (p. 204). If so, would that be the opening towards a new dynamic level, beyond biology and culture (as we know it)? With these questions Volk leaves the reader to ponder the content of this very, very rich and stimulating book.

Ths is not to say that everything under the sun has now been clarified. Volk fittingly ends with a confession of our (current scientific) ignorance before the mystery:

One point struck me after having spent much time investigating the levels—how they came to be and what they led to. The origins of levels tend to involve some of the largest enigmas to our understanding... For example, the origins of the eukaryotic cell, animals, agriculture, geopolitical states. These enigmas are fields of research unto themselves, fields of waving flowers announcing question upon question from all their petals glistening in the sun of reality. One can stand before these fields in rapture. Entering them is even better. (p. 188)

A CLOSE CORRESPONDENCE - AND A DIFFERENCE

Wilber has never dealt with the material and biological realms in any detail—he took them more or less for granted (atoms, molecules, cells, etc.) and only mentioned them in passing to demonstrate the validity of his "transcend-and-include" philosophy. Refreshingly, Volk does take the trouble to dive deep into these various levels and discovers principles and processes that give us a much deeper understanding. It also casts doubt on Wilber's sweeping statements regarding a universe that is "winding up" due to spiritual principles as of yet undiscovered by science (but envisioned during meditative states).

Wilber's expertise stands out in the psychological and cultural realm, where he sketches the "Stairway to Heaven" ranging from the premodern, through the modern and postmodern phases of cultural evolution, to the most advance mystical stages. A Wilberian keynote is the developmental step to world-centrism, to combat both etnocentric and egocentric tendencies in our current world. These two approaches seem to be complementary to me. Integralists would do well to study authors like Volk who entertain a deep fascination with big pictures but bring in more field-specific expertise, especially when it comes to physics and biology. While not aiming for a Theory of Everything Volk does provide a scientifically believable reconstruction of "how we came to be".

Still, in Wilber's Four Quadrant diagram a close correspondence between Volk and Wilber can be found—that is to say, when we limit ourselves to the Upper-Right (exterior-individual) and Lower Right (exterior-collective) quadrants. Here's the Four Quadrants diagram as it first appeared in Sex, Ecology, Spirituality (1995):

The levels or stages in the Right-Hand quadrants can easily be aligned with Volk's Grand Sequence, as the following table shows:

| TYLER VOLK | KEN WILBER |

|---|---|

| Planetary | |

| 12. Geopolitical states |

Nation/State Early State/Empire |

| 11. Agrovillages | Tribal village |

| 10. Tribal metagroups | Tribes |

| 9. Animal social groups | Groups/families |

| 8. Complex multicellular organisms |

Neural oganisms Neural cord |

| 7. Eukaryotic cells | Eukaryotes |

| 6. Prokaryotic cells | Prokaryotes |

| 5. Molecules | Molecules |

| 4. Atoms | Atoms |

| 3. Atomic nuclei | |

| 2. Nucleons: protons/neutrons | |

| 1. Fundamental quanta |

The match is actually quite close. Except for the lowest three material levels, which are lacking from Wilber's model. Wilber does mention quarks in SES in passing, as the following example shows: "Quarks (and all holons) respond only to that which fits their worldspace: everything else is foreign language, and they are outsiders" (p. 126). For Wilber, interoririty goes "all the way down", for Volk it is "things and relations":

This book is about the progression of an ever-larger nesting of levels of things, from purely physical to biological and eventually to cultural. For that progression to happen, things at all levels have to have relations. And the quanta of the Standard Model do. For us and our quest for a unified narrative with potential rhythms from quarks to culture, here is what we gain from the division of the fundamental quanta into matter-field quanta (which quarks belong to) and force-field quanta: the universe started with a basic creation and apportionment of things and relations. (p. 29)

At the opposite end of the spectrum, we could add a provisionary 13th level (“stable relations of nations” is his phrase when discussing future levels) at the top of Volk's Grand Sequence to complete the match. As you can see in the Four Quadrant diagram Wilber mentions three unspecified brain "structure-functions" (called SF1, SF2 and SF3), which underly the developmental cognitive stages of concrete-operational and formal-operational thought, and of so-called "vision-logic", a post-formal stage of development postulated by some researchers. It is unclear, however, how these conventional brain processes underlying developmental stages would follow the transcend-and-include pattern as they transcend the "complex neocortex"—not to mention brain correlates of meditative states and stages.

All in all, the range of Volk's model exceeds that of Wilber's—it diggs deeper into matter so to speak. Wilber's model exceeds that of Volk when it comes to possible spiritual stages of development—as a spiritual psychologist he has naturally explored the "farther reaches of human nature". But please note, as you can see in the diagram above, spiritual stages of development are not covered by the standard Four Quadrants model, apparently for their lack of clear equivalents in the other three quadrants of neurology (Upper-Right), culture (Lower-Left) and society (Lower-Right).

So the differences between Volk's and Wilbers holarchic models are not so much in the levels they propose—for these are rather uncontroversial and pretty much universally recognized as "major transitions in evolution"—as well as the mechanisms they suggest that cause us to move through these levels. Volk is very informative about the first eight levels of matter and life, providing examples from particle physics, chemistry and evolutionary biology to flesh out the details. Regarding the realm of mind/culture he switches to a collective terminology and focusses on the enlargement of group boundaries. Wilber, in turn, has almost nothing to offer in the realms of matter and life—whenever he references these, he often sounds like a creationist, even if a sophisticated one—but picks up in the realm of mind/culture, where he relies mostly on his extensive knowledge of developmental psychology, sociology and cultural anthropology.

Another difference is that Wilber explicitly makes room for the interior, "other half" or reality, as the Four Quadrants diagram above visualizes. Of course, since this model was designed originally to clarify human consciousness and its many aspects—individual, collective, cultural, social—it might very well be biased towards this level of consciousness. Wilber's model is rather "consciousness-heavy", so to speak. In his view, consciousness, or as he prefers to call it, "interority", goes all the way down to the lowest units of matter science recognizes. Consciousness is an inherent part of the integral universe. According to Wilber, both atomism and holism deal exclusively with the exterior, Right-Hand quadrants. But how to fit consciousness or interiority believably into the worldview of science? Are molecules really electron-hungry? Do unicellular organisms really want to become multicellullar? Did worms really want to be become whales? However, even from a purely exterior point of view it makes sense to acknowledge the long evolutionary history of awareness of some kind—going back to cells, and perhaps even to the atom. But what role exactly does it play in the pre-human stages of material and biological evolution?

Both authors speculate about a deeper logic or abstract principle that is at work throughout all of the levels, from the lowest to the highest. For Volk this is the principle of "combogenesis", in which elements of each previous level are combined to form the entities or "things" of the next level. This combination of elements can be effected through various mechanisms. Atoms may combine into molecules due to electromagnetic forces, but this obviously doesn't work when tribal villages combine into nation states and beyond. Wilber's developmental logic uses the abstract principle "transcend-and-include", in the sense that each higher level transcends the previous ones while including (parts of) them at the same time. Molecules transcend atoms but include them as well (as we saw in the water molecule mentioned above). As to the precise mechanism behind these transformative processes Wilber has a strong preference for quasi-metaphysical speculations, given his frequent use of the phrase "Eros in the Kosmos".[12]

Volk's approach is scientific from start to end. At the very least he is fleshing out both the Upper-Right and Lower-Right quadrants, especially regarding the evolution of matter and complex multicellular organisms like us, which hasn't been covered by Wilber to any large extent. But he also poses a challenge to the dynamic Wilber sees at work in evolution, a supposed "universal drive" towards complexity and consciousness working its way upward in nature and culture. Science has more sobering ways to account for the complexities we find in Nature.

NOTES

[1] Tyler Volk, Quarks to Culture: How We Came To Be, Columbia University, May 2017.

[2] Barry Wood, "Quarks, culture, combogenesis", Science, 19 Jan 2018, Vol. 359, Issue 6373, pp. 281. See: Barry Wood, "A multidisciplinary tour of cosmic history charts the "grand sequence" of existence", blogs.sciencemag.org, January 16, 2018.

[3] John Horgan, "How Quarks Turned into Cultures: Big-picture biologist Tyler Volk talks about his book on How We Came to Be", June 7, 2017.

[4] Tyler Volk, Metapatterns Across Space, Time & Mind, Columbia University Press, 1995.

[5] Interestingly, one of Volk's earlier works dealt with this topic: Gaia's Body: Toward a Physiology of Earth, MIT Press, 2003.

[6] Jeff Meyerhoff, Bald Ambition: A Critique of Ken Wilber's Integral Theory, Inside the Curtain Press, 2010. Chapter 1: Holarchy - 1a: Holons, 1b: The Twenty Tenets.

[7] Frank Visser, "The 'Spirit of Evolution' Reconsidered: Relating Ken Wilber's view of spiritual evolution to the current evolution debates", www.integralworld.net

[8] See for example: Holmes Rolston III, Three Big Bangs: Matter-Energy, Life, Mind, Columbia University Press, 2010.

[9] See Frank Visser, "Arguments from Ignorance: The "Frisky Dirt" Discussion So Far", www.integralworld.net, and David Lane, "Frisky Dirt: Why Ken Wilber's New Creationism is Pseudo-Science", www.integralworld.net

[10] This reminds me of Stuart Kauffman's famous phrase: “We are expected after all”:

Stuart Kauffman: “God, a fully natural God, is the very

creativity in the universe. God enough for most of us.”

If biologists have ignored self-organization, it is not because self-ordering is not pervasive and profound. It is because we biologists have yet to understand how to think about systems governed simultaneously by two sources of order. Yet who seeing the snowflake, who seeing simple lipid molecules cast adrift in water forming themselves into cell-like hollow lipid vesicles, who seeing the potential for the crystallization of life in swarms of reacting molecules, who seeing the stunning order for free in networks linking tens upon tens of thousands of variables, can fail to entertain a central thought: if ever we are to attain a final theory in biology, we will surely, surely have to understand the commingling of self-organization and selection. We will have to see that we are the natural expressions of a deeper order. Ultimately, we will discover in our creation myth that we are expected after all. (Stuart Kauffman, At Home in the Universe, Oxford University Press, 1996, p.112.)

Ironically, Wilber has often pointed to Kauffman as an ally in his resistance to neo-Darwinism:

I am not alone is (sic) seeing that chance and natural selection by themselves are not enough to account for the emergence that we see in evolution. Stuart Kaufman (sic) and many others have criticized mere change [chance?] and natural selection as not adequate to account for this emergence (he sees the necessity of adding self-organization). ("Some Criticism of My Understanding of Evolution", kenwilber.com, December 04, 2007)

But Kauffman is looking for naturalistic principles behind self-organization (soap bubbles forming spontaneously), giving "order for free", not transcendental forces. In Re-Inventing the Sacred (Basic Books, 2010, p. 6) Kauffman explicitly rejected any spiritual explanations for complexity by stating "God, a fully natural God, is the very creativity in the universe.":

Is it, then, more amazing to think that an Abrahamic transcendent, omnipotent, omniscient God created everything around us, all that we participate in, in six days, or that it all arose with no transcendent Creator God, all on its own? I believe the latter is so stunning, so overwhelming, so worthy of awe, gratitude, and respect, that it is God enough for many of us. God, a fully natural God, is the very creativity in the universe. It is this view that I hope can be shared across all our religious traditions, embracing those like myself, who do not believe in a Creator God, as well as those who do. This view of God can be a shared religious and spiritual space for us all.

"Creativity" is of course a slippery term—it can mean anything to anyone. Is it really a Principle/Person/Power or just a suggestive description for what we observe in Nature?

[11] In Sex, Ecology, Spirituality, Ken Wilber warns against holistic approaches that make the biological level (B) paradigmatic for the other two, of physics (A) and culture (C):

Volk seems to do justice to all three domains. Though his centre of gravity is in physics and biology, his focus on animal and human social groups gives him ample opportunities to introduce and discuss language, in- and outgroups, the "unbounded we", "seeing others as potential 'us'" and the expanded cognitive horizon of "mental time travel". Thus, his predominantly externalist approach takes quite some excursions into interiority and intersubjectivity to qualify as "integral".

[12] Frank Visser, "‘Eros in the Kosmos’: Mechanism, Metaphor or Something Else?", www.integralworld.net