|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Andrew P. Smith, who has a background in molecular biology, neuroscience and pharmacology, is author of e-books Worlds within Worlds and the novel Noosphere II, which are both available online. He has recently self-published "The Dimensions of Experience: A Natural History of Consciousness" (Xlibris, 2008). Andrew P. Smith, who has a background in molecular biology, neuroscience and pharmacology, is author of e-books Worlds within Worlds and the novel Noosphere II, which are both available online. He has recently self-published "The Dimensions of Experience: A Natural History of Consciousness" (Xlibris, 2008). SEE MORE ESSAYS WRITTEN BY ANDY SMITH TERRITORIAL CLAIMSA Further Reply to TorbertAndy SmithAn article by Bill Torbert ["Six Dimensional Space/Time"] was recently posted on the Integral World site, in which he proposes that we understand human experience in terms of six dimensions, including not only the familiar three dimensions of space and one of time, but two additional dimensions of time [see Table 1]. Since I have also written extensively on understanding experience in terms of dimensions, including three of time[1], Frank thought I would be interested in Bill's article, and asked me to comment on it. I made some criticisms of it that Frank passed along to Bill. Bill, in turn, replied that I had misunderstood or misinterpreted much of his views.

Table 1 - Six Dimensional Space/Time according to Torbert

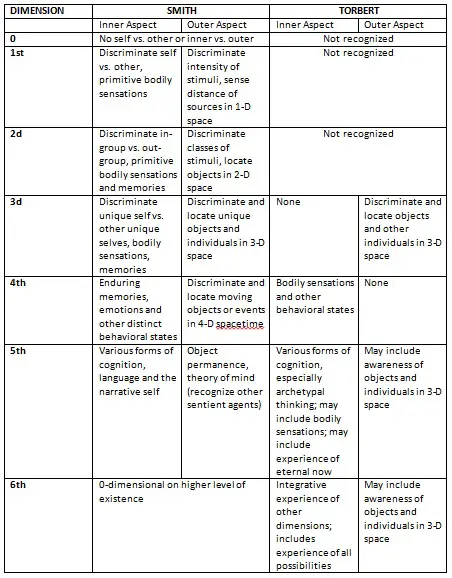

My initial response to Bill's article was brief, as I was simply giving Frank my impressions following a quick reading. I did not feel anything more was demanded, given that the article is just an overview of his ideas, and does not develop the arguments in detail. Prompted by Bill's response, though, I will now provide a somewhat more detailed critique, using as a starting point that response. Timely Action and Timeless ActorsBill's reply begins:  Bill Torbert In his first contemptuous paragraph, he claims I ask no new questions and that 'everyone knows what the questions are.' Wish it were so! The question that I have been asking throughout my career, and that no other social scientist has focused on in its moment-to-moment practicality and existential methodological challenge, is a question implicit in any attempt to practice from a late action-logic integral developmental perspective, but not one that other developmental colleagues have seriously taken up (the French philosopher Badiou takes it up most explicitly, but at a highly abstract level). This question, which in the article I call the aim of human development is: what action is timely now? This is a question that can never be answered once and for all, either philosophically or empirically, but rather can come to inform our daily awareness, contemplative turns, and actions more and more deeply as we gradually recognize its power to transform us and the interactive situations in which we each participate. These are the questions I was referring to, as found in Bill's original article: The 'four-territory' construct or axiom gives us access to a multitude of fundamental questions, if we use the idea to do existential, living inquiry in the present moments of our lives. How can we cultivate the spacious awareness of all four territories of experience more often? How might we accept feedback from ourselves, others, and the sheer object-ing objectivity of the outside world that would show incongruities between our intent, plan, action, and effects on the outside world? How might we cultivate relationships with others that give them equal access to such spaciousness within themselves? Relationships, that is, not of uni-directional, unilateral power, but of mutually-respectful and potentially mutually-transforming power? Relationships that encourage a trustworthy testing of the validity and the transformational learning value of feedback among us? How can we gradually cultivate an ongoing balancing among our first-person passions, our second-person compassions, and our third-person dispassions? How can we learn to act in ways that are increasingly uniquely crafted to be situationally timely for this event, from the diverse perspectives of oneself, the others present, and the larger social/natural container(s) 'holding' us? So the questions he asks include how can we “accept feedback from…others”; “cultivate relationships with others” that are “mutually-respectful and potentially mutually-transforming”; engage in “transformational learning”; and “ongoing balancing”…Seriously? These questions are new? They strike me as exactly the same questions, or kinds of questions, that people in the human potential movement have been asking for a very long time. And I could say the very same thing about questions he raises or implies later, in his sections on time, when he says, e.g., that “some of us feel bored”, “we don't know what to do”, “our …fantasies are…disconnected from…reality”, we must decide “which priority to follow”, and so on. And yes, I do understand that all these questions are asked in the context of timely action, of “existential, living inquiry in the present moments of our lives”. And I suppose Bill honestly believes that means he is asking these questions in a different way from the way they've been asked before. Well, maybe I've become jaded from all these New Age salesmen—Erhard, Chopra, Wilber, and on and on and on—but it all sounds very much the same to me. Tap into potential you never knew you had. Improve your relationships with others. Balance your diverse interests. In other words, trying to link spiritual practices to human development. I really don't see that Bill is doing anything different here. Sure, his language is a little different, but everyone uses different language. You have to in order to distinguish yourself from the competition. For example, consider this passage from the section on the sixth dimension: Over a period of decades, I discovered first that, when planning a future meeting agenda, or class, or consulting intervention, if I 'forced' strategizing by creating agendas from outlines of decisions to be made, the subsequent meetings tended to be relatively lifeless events. On the other hand, if I could nurture an alert, relaxed state within myself, then a kind of meditative, creative imagination suffused with color and feeling would develop and produce a sense of the energetic shift necessary at the core of whatever work was in the offing. In a kind of waking-dreaming, I would find myself spontaneously immersed in imagining myself and others interacting in the forthcoming event. Taking notes of these 'process-thoughts' would generate an agenda consisting of exercises to help us think and decide things together. These agendas were both an exploration and a joy to enact, challenging me to generate 5th and 6th dimensional awareness during the event, and seeming to encourage others' creativity and the production of inspiring results to which we were deeply committed. Only after some time did I develop the patience—not to accept the first creative offering, leave the state, and craft a result—but rather to remain in the open, listening state and experience the “rain of possibilities.” My experience of this 6th dimension is, I am quite sure, minimal and inadequate to its full timely and timeless spaciousness. I include this short discussion of the 6th dimensional rain of potentially timely possibilities only as a small effort to help others' future action inquiry. Translation: Rather than preparing for a meeting by creating a rigid, pre-conceived agenda, I have found it more fruitful if I remain somewhat flexible, imagining myself actually in the meeting and in this way anticipating what others might say. The agenda I eventually form from this process seems to be more effective in encouraging dialogue and bringing out the best ideas in all of us. Does one really need to bring in the 6th dimension to come up with that insight? Can't one come to the same conclusions just from observations of human behavior, without any theorizing at all? Preparing for a future event by imagining it is a very old trick, well known even before the human potential movement began. Also well known is the effect of relaxation on creativity, of letting unconscious processes take over. Isn't the attempt to explain these in terms of the sixth dimension just a catchy way to dress up what happens? Bill may be an excellent communicator and facilitator, he may have developed an uncommon ability to help others formulate and articulate ideas that they find helpful in their lives. But none of this necessarily provides support for the concept of higher dimensions. I imagine that without this concept, he could be just as effective as he is now. So to conclude this part, I think it's one thing to propose a theory of experience involving dimensionality, which I also have done, and quite another to claim that it will help people live better lives, which I don't. Like most scientists, I have a deep belief that the more we know, the better off we will be, but I generally don't venture beyond this. I don't have anything against people who do, but I feel that most of them are simply using some theory as a way to make their ideas seem more different from everyone else's than they actually are. Moreover, when one brings in the notion of higher forms of consciousness, of spirituality, meditation, and so on, there is an additional potential problem. This problem was raised by Conrad Goehausen a while back, which I discussed in a mostly favorable light in my article Aeternum per Tempore. Basically, the argument both of us are making is that human development is a side effect, and should not be the goal, of spiritual practices. I think this point is often lost among followers of Gurdjieff/Ouspensky (mentioned in the original article by Bill, and whom I myself have been deeply influenced by), who certainly emphasized the importance of human development, but mostly I believe as a way of ensuring that spiritual practice was balanced. Today, in contrast, the connection seems to be made more as a way of attracting followers. If you want to sell something, you have to make it look good to potential buyers, and that means promising to them that the wants and needs of their ordinary lives will be fulfilled in some manner. Meditation is the process of awakening. Awakening will not necessarily make one a better person, by any of the various ways that that term is understood. It will not necessarily improve your relationships with other people, make you more balanced, enable you to be more efficient at your job, or make a lasting contribution to the human race. It would be wonderful if it accomplishes some or all of those things, but its success is not measured by any of them. Its success is measured by awakening. Period. What Goes with the Territory?In his recent reply, Bill states that I have misunderstood his argument about dimensions: I don't know what led Andy to conclude in his second paragraph that I understand the four territories of experience in reverse order from him (perhaps the association of lower numbers with territories that I later show represent higher dimensions?). In any event, a more careful reading will show, we do not disagree about this. Yes, the association of lower numbers is what threw me off, and particularly this statement in his original article: My first mathematical intuition is that the proper number to associate with each “territory of experience,” is 0 for 'bare attention,' 1 for thinking, 2 for inner sensation, and 3 for outside world. When one is writing about dimensions, and applies the numbers 0,1,2,3 to four territories that one previously describes as inhabiting different dimensions, what does one expect the reader to conclude? Bill even explicitly says that the outer world is one of three-dimensional space, and 0 is a reasonable way to describe a fundamental awareness. Why wouldn't a reader--literally--put 1 and 2 together, and infer from that that these other numbers refer to the dimensionality of the territories? Why else would there even be a discussion about numbers? Now to be fair, Bill does go on to say later that the territories beyond the external world are all composed of temporal dimensions: A question that arises is: what kind of dimensions do the other three more inward territories of experience re-present? My second mathematical/ ontological/ epistemological intuition is that the universe we can potentially experience and at least partially know is organized in six dimensions So my bad, he does associate the other territories with higher dimensions. My apologies for missing this. But I don't think it's too difficult to miss, given that a) he originally associates these territories with lower numbers, without ever emphasizing to the reader that these numbers are not meant to correspond to dimensions; and b) he doesn't follow the statement that the universe of experience involves six dimensions with an explicit statement that each of these territories is associated with a dimension of time. Even after re-reading the above passage several times, I felt left hanging. Yes, there are territories of experience beyond the external world, and yes, there are six dimensions to experience, but they aren't connected immediately and emphatically. Rather, the explicit connections are made later, buried in a lot of discussion: while all moving animals and humans have a rudimentary sense of the fourth dimension of temporal duration that is specifically associated with the second territory of experience—our own inner sensation of ourselves, still or in movement. Just as the experience of the first dimension of time is especially associated with the embodied awareness territory, so the experience of the second dimension of time is especially associated with the archetypal thinking territory. And even here, he isn't emphatic. Rather than stating “the fourth dimension is associated with the second territory”, he alludes to it, as if it's already understood, when he says “the fourth dimension that is specifically associated with the second territory”. We're supposed to know something that we in fact to that point have not been told. His discussion of the fifth dimension is also somewhat confusing, because prior to the above passage connecting it to the third territory, he says: This five-dimensional experience of time and space seems to touch and integrate all four territories of experience at once—the noumenal (0), the archetypal (1), one's present embodiedness (2), and the outside world (3).[3] It also seems to embrace the fourth dimension of duration without disconnecting from the present, sometimes revealing our life's journey as if in a single lightning flash. This passage states that five-dimensional experience integrates all four territories—not only the preceding or lower territories of the external world and sensations, but also the apparently higher noumenal. This is not what one would expect of dimensional worlds, and is unlike the four-dimensional experience, which is not said to integrate anything. To be consistent, four-dimensional experience should be said to integrate three-dimensional experience with durational time, while five-dimensional experience integrates four-dimensional experience with the second dimension of time. And the confusion doesn't end there. There is a further problem with his presentation of the fifth dimension. Earlier in the article, Bill describes the third territory as “the ongoing thinking of these thoughts I am writing.” This description implies that it applies to all kinds of thinking, just as the second territory applies to all kinds of sensations. And if this model were to be a fairly complete account of human experience, this is just what one would expect. But in the section on the fifth dimension, he describes it as “especially associated with the archetypal thinking territory”, and further says that we have “very occasional, fleeting experiences of this kind of time”. If we have only fleeting experiences of the fifth dimension, clearly the latter can't be associated with common, ordinary thought processes. In fact, nothing in his discussion of the second dimension of time suggests that it has anything to do with ordinary thought processes. This implies that a major aspect of human experience is missing from the model—and of course, adds to confusion that can easily lead a reader not to interpret the higher territories as being associated with higher dimensions. Finally, nowhere in the section on the sixth dimension does he actually say that it corresponds to the fourth territory. The word “noumenal” never appears in this section. He says or implies that it integrates all four territories, as we would expect it to do, but as we have seen, he also says that about the fifth dimension. So to summarize, while I now understand that Bill is associating the higher territories with higher dimensions, I think he could have and should have been much clearer about the connection. Not only does he not state this connection emphatically at the outset, but his discussion of the fifth dimension creates some confusion over whether it's associated with all kinds of thinking, or only certain forms of it. I'll also point out that Frank, I assume, also read his original article and my original response, yet Frank apparently did not see any problem with my interpretation of the higher territories associated with lower dimensions. My mistake did not jump out at him. The Dual Aspects of ExperienceA lack of clarity in associating sensation and thinking with higher dimensions is not the only problem, though. I don't feel that Bill provides a coherent explanation for why these territories even should be associated with higher dimensions. I have already pointed out that his description of the experience of the fifth dimension as fleeting makes it seem very different from ordinary thought. He seems to regard it as some kind of peak experience, but in that case he lacks an explanation for exactly where ordinary thought fits in his scheme. There are further inconsistencies. He identifies the second territory with sensations, and says these are associated with movement, and thus the first dimension of time. I think it's arguable that many sensations are experienced with very little sense of time. But even more important, the sense of time does not emerge with this kind of experience. Time is an intimate part of all of our experiences of the external world, where living and non-living things are constantly changing or in motion. This has major implications for how all the territories he identifies are understood. Here is what I think Bill is missing. All dimensions of experience are associated with both the external world and with inner processes such as sensation, emotions or thinking. For example, four dimensional experience is associated with awareness of bodily sensations—as when Tinbergen's herring gulls perform a specific behavior pattern—but also with experience of the outer world, when they recognize the behavior pattern of another gull as sending a specific signal to them. The two go hand in hand. Ability to experience an extended dimension of time is critical to both. The same point applies to five-dimensional experience—which, as an apparent major point of disagreement with Bill, I don't regard as an occasional event, but the normal state of human cognition. The inner aspect of this experience is manifested in thinking, language, and other cognitive processes. But it also has an external aspect, manifested in object permanence, the ability to understand that objects continue to exist when they aren't in our immediate awareness. While object permanence is a critical component of language, an inner aspect of five-dimensional experience, it also affects the way we experience the outer world. It has been very well documented, for example, that much of our experience is not the result of immediate stimuli, but rather has been pre-constructed from memories, from expectations about what the external world should look like. We carry around in our heads frameworks that automatically come into play when we, e.g., walk into a room, interact with some object, or encounter another person. This is a direct result of having experience of what I call a second dimension of time, and again, it goes hand in hand with the inner aspect. Moreover, it follows that just as the higher territories are associated with external as well as internal experience, so are the lower territories associated with internal as well as external experience. Thus three-dimensional experience not only accesses a three-dimensional environment, but is generally closely related to the ability to identify oneself as a unique individual. This is the inner aspect of three-dimensional experience. In my system, there are also two-dimensional and one-dimensional forms of experience[2], and these, too, have an inner or subjective aspect as well as an outer or objective aspect. The inner aspect of two-dimensional experience is the ability to identify oneself as a member of a group or social organization[3]. The inner aspect of one-dimensional experience is the ability to distinguish self from other. This contention that all experience has both an external or objective aspect as well as an internal or subjective aspect is supported by a large body of evidence, discussed in detail in my book The Dimensions of Experience. But it also follows logically from an understanding of the basis of experience. In order to experience an outer world, an organism has to have a nervous system that responds to external stimuli. Any nervous system that can respond to external stimuli can also respond to internal stimuli. Moreover, the way it responds to external stimuli—the number of dimensions it can access--is determined by the organization of the nervous system[4], so it follows that this organization will also determine the way it responds to internal stimuli. So external and internal experience go hand in hand, and are determined and limited by the same principles of organization. So I think Bill oversimplifies when he describes the lowest territory as the external world, and when he describes the other territories as “inner” or “more inward”. This same view very frequently leads people to regard spiritual practices as oriented towards something inner, distinct from the external world. Higher dimensions and spirituality are just as much associated with the outer world as with the inner world. This was a point often made by Gurdjieff/Ouspensky. They never regarded meditation as just sitting quietly and focusing on breathing or inner images, but living in the world while trying to become more aware of it. Bill's writing certainly suggests that he has some appreciation of this. While he describes the first territory as apparently entirely external, and succeeding territories as largely if not entirely internal, he emphasizes the possibility of integrating them, so that at least an individual is clearly capable of experiencing both the external world and internal events together. But how does this integration occur? I find Bill quite vague on this. Early in his original article, he gives an example of experiencing the three territories simultaneously: I am also experiencing frequent moments when I am aware of the seashore outside the train window, the sensation in my fingers as I type, and my thinking, all at once. This is described as a common experience, and in this passage, as I noted before, he's viewing ordinary thought processes as the third territory. But later, when he discusses the fifth dimension, and associates it with only some thought processes, his view of integration also changes, to one of a rare, peak experience: almost all of us have very occasional, fleeting experiences of this kind… it is always now, the eternal now. The experience of this moment—of, say, mutual, loving intimacy with this person—is all we want and have ever wanted. 'Time' feels full. We are in no rush whatsoever to get anywhere else. No doubt experiences like these occur, and reflect some integration process, but what I think deserves far more emphasis is that integration of the different territories is going on all the time, even in our most ordinary, mundane experiences. The key to it, I contend, is that experience at every level/dimension is both external and internal. It isn't just that thought allows us to understand the external world differently, as a different dimension (though it can and does do this). It's that thought redefines what we experience as the external world, providing it with the same dimensionality as thought itself. In other words, for the most part we do not actually ever experience a purely three dimensional world external to ourselves. I think even most scientists and mathematicians, who ought to know better, miss this point. Much like the proverbial fish that is so accustomed to the water it's immersed in that it doesn't recognize that this medium actually exists, all our experience of the world is so permeated with time that we don't recognize what an enormous difference that time makes. In fact, my claim is that we experience a five dimensional world, in which three dimensional objects and living things have a permanence to them. We don't see or understand them in some always-changing/never-changing now (which would have to be the case if experience of the three dimensional world were devoid of any time), but as objects that are existing and sometimes moving or changing over a finite period of time during which we observe them (the fourth dimension), and which have existed before this and will continue to exist after this (the fifth dimension). When you return to your home in the evening after a day at work, it doesn't suddenly pop into existence. It's part of a world that was there before you got there, and that's how you actually experience it. This permanence is provided by concepts that are not simply added to an object after we experience it, but are part of the actual process by which we experience it at all. With some possible exceptions, we are incapable of experiencing the world except in this manner. This is primarily how the three dimensional world is integrated with higher dimensional experience. Lower organisms, which lack these concepts, do not see the world in this way. Though in one sense they must experience much the same world we do, being aware of the same objects, other organisms and environment, their experience when encountering them must be quite different without these concepts as part of their makeup. As I alluded to above, there may be some exceptions to our experience of the external world as five-dimensional. In moments of great stress, for example, when lower, non-cognitive or instinctual brain processes become prominent, we may have a somewhat purer experience of three dimensions, less integrated with time, certainly less integrated with the second dimension of time. Young children, particularly pre-language, almost certainly also experience the world in this fashion. And certain types of brain injuries or pathologies may also compromise our ability to experience the world in this fashion.[5] Experiencing vs. Understanding TimeImplicit in the preceding discussion is a critical distinction--between experiencing a dimension and understanding it—that I want to say a little more about. In my initial reply to Bill, I said he misunderstands how critical the experience of time is to humans. In response, he says: My attempt there and later in the article was to highlight how much more robust our competence in durational time can become than most of us imagine. Competence, in this context, means understanding, not experience. This is clear from the statement in the original article that drew my criticism: by adulthood a very high proportion of us come,—through stories, relationships, and more formal types of education—to gain a rudimentary competence in dealing with the fourth dimension. Virtually all of us gain a sense of what an hour is or a week and how to get to a meeting on time, as well how to name and negotiate general behavioral patterns over time (e.g. the beginning, middle, and end of a project). This is true, but this competence is not a matter of experiencing first-dimensional time, but of understanding it through concepts, which is to say, being capable of experiencing what I call the second dimension of time.[6] We generally do not and cannot experience a week as a week, but we are nevertheless capable of understanding what a week is. Likewise, in order to assign times to appointments, let alone to keep them, requires having certain concepts. Experiencing the first dimension of time—simply a linear flow of time, as evidenced by changes in ourselves and in the world around us--does not require any concepts at all. A child or a higher vertebrate is just as capable of doing it as we are. It's the fifth dimension that distinguishes us from other animals, and to a much more limited extent, from each other. It allows us to quantify time, to give names to different periods of time, and in this way to order our lives according to time. Bill adds: I agree with Andy that children and animals begin gaining this competence earlier than adulthood. He is wrong of course that an ability to maneuver through durational time is universal; a small proportion of humans are ill or disabled. I think the claim that experience of time isn't universal is silly. Yes, one can always find pathological cases that disprove the assertion that any statement about our species applies one hundred percent. Do we all have five fingers on our hands? No. Do we all have 206 bones in our body? No. Do we all even have a complete cerebral cortex? No. For all practical purposes, anything that is considered a defining feature of the species is universal, and that certainly includes our experience of time. To repeat, differences among individual humans are in the understanding of concepts of time, and as far as duration goes, I would say those differences are pretty minimal. Virtually all adult humans, at least those educated in the modern world, understand that time stretches back and in the future essentially infinitely. To summarize and conclude, Bill Torbert proposes an understanding of human experience involving six dimensions, three spatial and three temporal. I also believe six dimensions are necessary to understand experience, though there are some major differences between our views. Beyond these differences, I think Bill needs to be clearer in how he understands the relationships between these dimensions and our actual experiences. The reader may find helpful the following table that compares my view of dimensions to Bill's (as I understand his):

Table 2 - Comparison of the Dimensional Models of Smith and Torbert

ENDNOTES

REFERENCESDeutsch, D. (1998) The Fabric of Reality. New York: Penguin. Sacks, O. (1988) The Man who Mistook his Wife for a Hat. New York: Touchstone. Smith, A. (2008) The Dimensions of Expericence: A Natural History of Consciousness. Xlibris, Corp.

|