TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

SEE MORE ESSAYS WRITTEN BY ANDY SMITH

SAME VALUES, DIFFERENT GROUPS

Why Liberals and Conservatives

Talk Past Each Other

Andy Smith

America today, where political debate is more open and accessible than ever before, is more politically polarized than it has been in decades, perhaps to the greatest degree in its history.

Americans will elect—maybe, re-elect—their President in about five months, and the campaign season is in full sway. Actually, it always is, nowadays. None of the issues being argued over—the economy, health care, immigration, national defense, and so on—is new, nor are the positions on them being staked out by each candidate. Thanks to the internet, political discussions now go on 24/7, in every season of every year.

One might think, naively, that because the internet gives everyone a soapbox, everyone a chance to put his views and their rationale out in the public domain, that some progress might be made towards achieving a political consensus in America. One might expect that since every issue of importance to our lives is subjected to closer scrutiny than ever before, with every idea, claim or argument receiving feedback from dozens, hundreds or thousands of people with somewhat different views, that there might be an emerging consensus on some of them, or at least areas of general agreement. One might hope that because there are, and have been for a very long time, only two major parties in the U.S., that they might by now have taken at least some tentative steps towards resolving their differences.

This does not seem to have happened. If anything, the greater public expression of political views has increased, not decreased, individual differences. While there are undoubtedly other factors at work, it surely is not just coincidence that America today, where political debate is more open and accessible than ever before, is more politically polarized than it has been in decades, perhaps to the greatest degree in its history. Neither party, in the eyes of the other, is willing to work, to compromise, with the other at all.

Writing in Vanity Fair, Todd Purdum notes that

the connecting tissue between the parties has disappeared. For much of the 20th century, ideological affinities between southern Democrats and conservative Republicans, on the one hand, and between urban and northern Democrats and moderate and liberal Republicans, on the other, not only allowed but effectively required cross-party cooperation to get anything important done.

Today there are no such cross-party incentives for cooperation…Barack Obama received not a single Republican vote for his health-care initiative. An analysis by National Journal of roll-call votes in the 111th Congress, which ended last year, found that, in the Senate, the most conservative Democrat was slightly more liberal than the most liberal Republican, and nearly the same was true in the House. That is another way of saying that the extent of the common ground between the two parties is virtually nil.

Why is the gulf between liberals and conservatives so apparently unbridgeable? Traditionally, it has been said that most of their differences come down to the role of change: liberals generally embrace it, conservatives tend to resist it. To the extent this is true, they embody two major drives that are necessary to all living things: growth and self-maintenance. They represent the interplay of these forces on the social level. Liberals are generally more concerned with expanding and improving society, conservatives in preserving and protecting it.

That should tell us right there one reason why America is so polarized. We are in the middle of an enormous transformation now, driven by advances in technology, and the pace of change—political, cultural, and social as well as scientific and technological--is perhaps greater than ever before in our history. This can only exacerbate the tensions between those who favor change and those who resist it, for the stakes are much higher now.

Given these stakes, surely it's important to try to understand this conflict better—that is, to step back and take as an objective view as possible of these two political systems. For the first time in human history, this is actually occurring; political views are not simply being expressed and debated, but studied scientifically. Researchers are seeking to learn why people have such fundamentally different views of change, and how these views lead them to very different conclusions on how to deal with the issues crucial to our lives.

Such studies may or may not help us resolve our political differences. But at the very least, they should help supporters of one view understand those on the other side better. From a purely practical point of view, this understanding should make it easier to appeal to them, or as philosopher George Lakoff (2002) puts it, frame issues in a way that those sympathetic to one view may better see why a different view may be in their interests. I think the most important potential of these studies, though, as with all research, is to help us see our future, or possible futures, more clearly.

Inside the Political Brain

With the development of brain scanning techniques near the end of the last century, neuroscientists could for the first time correlate mental activity, as described by human subjects, with neural processes in specific parts of the brain. Recently, scientists have applied this approach, together with more traditional psychological approaches based on questionnaires, to probe the minds of individuals self-described as liberal or conservative. The results to date, as summarized elegantly by Andrea Kuszewski, suggest some intriguing differences that are generally consistent with what we might expect.

Liberals tend to have a larger and more active anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). This part of the brain is associated with evaluating data, detecting errors or conflicts in information, and finding significance in patterns of stimuli. Most important, the ACC plays a key role in regulating emotions, that is, allowing the brain to find rational solutions to problems without being overwhelmed by emotional reactions to these problems. In other words, to stay calm in the face of challenges. This generally accords with behavioral research indicating that individuals who describe themselves as liberal are relatively comfortable with change, with novelty, with ambiguity, and complexity. It also seems to support observers like Drew Westen (2008), who argues that most Democrats fail to understand the importance of appealing to the emotions of voters.

Conservatives, according to the studies summarized by Kuszewski, tend to have a larger and more active right amygdala. The amygdala plays a key role in emotional responses, and in particular, forming emotional memories of events. Every American in my generation remembers exactly where she was and what she was doing when President Kennedy was assassinated. This is because highly emotional events are much more likely to result in memory consolidation. This process occurs to a large extent in the right amygdala. Conservatives, it turn out, tend to react more emotionally to salient events than liberals, and are more likely to find value and meaning in such emotional events, as opposed to the liberal tendency to find meaning in the weighing and processing of information. In other words, conservatives tend to judge an idea based on the emotional impact it has on them. As Kuszewski puts it, “They would be more likely swayed towards a belief if it touched them on an emotional level.” Again, this resonates with Westen's views.

While there is no question that our views are shaped to a very large degree by life experiences, and especially by our parents, these studies open the door to the possibility that brain differences that are inborn, or at least determined very early in life, may also play a role. Other studies have provided more direct support for genetic inheritance of political orientations (Eaves et al.1999; Hatemi et al. 2011). In fact, the understanding of political views emerging from these studies is that they are determined by major personality traits, particularly, as I suggested earlier, openness to change. There is considerable evidence that major personality traits in general are determined to a large degree by heredity as well as by environment (Robins et al. 2005).

Such studies, though, don't help us to evaluate the truth or the utility of these views, any more than earlier studies locating emotions in the brain told us anything about the value of those emotions, or current studies identifying the neural correlates of particular thoughts or ideas in the brain tell us anything about the meaning of this mental activity. A more relevant question to ask might be: why have these two contrasting views persisted for as long as they have? Human beings have always had conflicts with one another, but the political divide goes much deeper than quarrels about access or ownership of resources. It's really a meta-quarrel, the argument being about the rules that we should have for settling such everyday disputes. It occurs not between strangers, which might be understandable, but among people who share a common background and history, often even pitting family members against each other (a powerful metaphor for political disagreement, as we shall see). Why has it thrived amidst all these factors unifying us?

We're All “Socialists”

To address this question, it's natural to take an evolutionary approach. If we differ fundamentally in our orientation to change, in all its forms, then presumably these attitudes evolved because they provided some function critical to survival. Jonathan Haidt (2012), who has been a pioneer in the study of political views, argues that the key evolutionary event in this regard was the formation of the first human groups, families and tribes. Individuals of course must modify their behavior when they interact closely with others, so one could reasonably say that the formation of groups was the beginning of politics.

Haidt believes that conservatives tend to be more “groupish”—that is, exhibit behavior in support of the group or social organization—than liberals. In his recent book The Righteous Mind, he identifies six general classes of values, or what he calls “moral modules”, which he believes hold the key to understanding the differences between liberals and conservatives. These are care, fairness, liberty, loyalty, authority and sanctity.[1] The first three of these, according to Haidt, are oriented towards promoting individuals, while the last three are associated with strengthening groups. And in Haidt's view, liberals tend to place more emphasis on the individualist modules, while conservatives, while emphasizing the group modules, endorsed all of them to some extent.

Haidt is surely correct when he argues that values such as loyalty, authority, and sanctity emerged during a very early period in our evolution, and played a critical role in maintaining the integrity and stability of the group. However, his equating of liberals with individualism and conservatives with orientation to groups seems too simplistic. Like other researchers in the field, Haidt views the conflict between liberals and conservatives as a battle of groups, with members of one group (the in-group) opposing members of the other group (the out-group). But given that this is so, how can people who call themselves liberal neglect or ignore group values any more than conservatives? If liberals view themselves as members of an in-group, and conservatives as members of an out-group, don't liberals have to value loyalty, authority and sanctity just as much as conservatives do? And in fact, it's easy to provide examples demonstrating that they do.

Consider the liberal support for political correctness, which dictates all kinds of behavior that individuals are supposed to engage in or refrain from. Or affirmative action, which tells schools, businesses and other institutions the kind of individuals they must accept as students, employees, and so on. Or the massive and constantly growing number of governmental regulations that encroach upon every aspect of our daily lives. These are clearly forms of group authority that liberals are more comfortable with than are conservatives. Indeed, it is precisely in response to the liberal preference for this kind of authority that so many conservatives describe the current Democratic administration as socialist—i.e., favoring the authority of the group over that of the individual. Liberals are frequently accused of being socialists or collectivists. When was the last time anyone accused a conservative of being socialist?

Liberal examples of group loyalty are also easy to find. They include solidarity in labor unions, unity in social protests like Occupy Wall Street, and devotion to activist organizations, such as those working on environmental issues. As members of such groups, liberals readily pledge their allegiance, in the form of time, effort, money, and sometimes even their freedom, to achieve the goals of the group. Moreover, liberal causes that go beyond America's borders, for example, movements against war, global warming and poverty, are frequently couched in almost religious terms. Liberals are particularly likely to view the environment as sacred.

Conversely, conservatives frequently favor beliefs that, according to Haidt, are supportive of individuals. Conservatives favor liberty in the form of free markets, in which individuals are allowed to engage in economic transactions with minimal interference on the part of the government or any other form of group authority. The conservative endorsement of fairness is clearly expressed in opposition to high taxes and social welfare, which conservatives view as cheating individuals out of the fruits of their individual labor. When conservatives oppose federal regulations, they are not only striking a blow against authority, but expressing care for the individuals and businesses burdened by these regulations.

So liberals clearly favor values oriented towards groups in some instances, while conservatives sometimes favor values oriented towards individuals. In fact, upon closer examination, the distinction between what Haidt calls individual modules and those that he calls group modules breaks down somewhat. While values such as care, fairness and liberty appear to be targeted to the individual, they also have clear benefits to the group, just as much as loyalty, authority and sanctity do. Caring behavior is of course exhibited by many other animals than ourselves—most higher vertebrates show care towards their young—and evolved in association with the simplest and most fundamental group of all, the family. Fairness probably also has its origins in the family, where each of the progeny has to be treated more or less equally if they are all to survive. Both forms of behavior are crucial to the survival of families and generally to larger groups as well.

What about liberty? There is no question that there is some conflict between any group and its individual members, who often must constrain some of their behavior for the sake of group cohesiveness. Yet liberty also plays a vital role in the survival of groups. A good example is provided by free speech, one of the most fundamental forms of liberty recognized by humans. Speech is a social phenomenon, and very clearly evolved because it increased the stability and cohesiveness of groups. But language is not static; new words and ideas are constantly evolving, and must, if the group is to meet new challenges. Free speech is a strong motivating force for such change.

Conversely, the so-called group modules have benefits for individuals. The authority and loyalty with which conservatives regard local police forces and strict laws against crime are intended to protect individuals, to give them the freedom to walk the streets safely and to maintain ownership of their homes and businesses. The sanctity of marriage provides protection for both partners, particularly traditionally for the woman, against divorce. Likewise, on the liberal side, federal regulations are intended, among other things, to protect individuals against accidents in the workplace or the health effects of pollutants. Loyalty to large organizations like labor unions protects individuals against unemployment. The sanctity with which many liberals regard the environment ultimately means protecting the source of our sustenance.

To summarize, all six of the moral modules that Haidt identifies are in an important sense oriented towards both individuals and groups. They very clearly have, or can have, benefits for both. I will discuss the individual benefits in more detail later, but for now I want to emphasize the ways in which they benefit the group. I think the distinction that Haidt is missing here is the different roles that these modules play in the group. What he calls group modules—authority, loyalty and sanctity—function primarily to stabilize the group, to increase the cohesiveness among its members. They bind members more closely to the group, making it less likely that will choose to live outside of the group, or seek membership in a different group. The so-called individual modules, on the other hand, promote the growth of the group, allowing it to integrate new members, as well as new kinds of relationships between existing members. These kinds of behavior permit the group to change without losing its identity as a group.

This conclusion has two surprising, even counter-intuitive, implications. First, it suggests that whatever the differences are between liberals and conservatives, they involve our relationships to groups. Morality is usually thought of in terms of the benefits, as well as responsibilities, it has for individuals. Haidt, I think, has made an important insight in suggesting that some of our most important moral values are directed not to individuals, but to groups. My claim is that in fact all our moral values are like this, though they do have individual benefits as well. As a corollary, all the policies promoted by politicians, liberal or conservative, are targeted just as much to groups as individuals.

The second implication is perhaps even more unexpected. Earlier I noted that almost everyone agrees that the essence of the liberal-conservative difference boils down to their view of change, which is closely related to growth. Yet now I have claimed that both liberals and conservatives value both change and stability under certain circumstances. If this is the case, what is the key factor distinguishing them?

To address these issues, we must begin by understanding that there are many different kinds of groups that we belong to. Liberals and conservatives, I will argue, view these different groups very differently.

All in the Family

Another author who, like Haidt, contrasts liberals vs. conservatives in terms of individuals and groups is philosopher George Lakoff. In Moral Politics: How Liberals and Conservatives Think, Lakoff argues that these two major political belief systems are guided by different views of the family. Liberals, according to Lakoff, believe society should function as a nurturing, relatively permissive parent, while conservatives regard it as a relatively strict, authoritarian parent. Like Haidt, then, Lakoff sees so-called group values—what I call group-stabilizing values--like authority and loyalty as more the province of conservatives, while individual values—or more accurately, group-growth values--like liberty and care are associated more with liberals.

As I explained earlier, the evidence simply does not support this distinction. Both liberals and conservatives support both kinds of values under certain conditions. However, I believe that Lakoff has put his finger on a key element of both political belief systems. This is the notion that our models, both liberal and conservative, of how society should treat its citizens are based on the family. This is quite logical. The family was the first social organization to evolve, and of course it is also the first social organization that all of us have membership in. Our earliest experiences in getting along with others, in both an evolutionary and developmental sense, were formed by the relationships we have with our parents, siblings, and often, more distant relatives. Given the ancient, enduring history of the family, it is not surprising that we would turn to our experiences here in guiding our life in more complex societies.

In other words, both liberals and conservatives view society, or want to view society, as one big family. They want a society whose members treat each other, as much as possible, as they would their own kin. One way of understanding human history is to say that families gradually expanded to the point where their members no longer knew, were related to or understood each other, and we have been trying ever since to bring them all back into the fold.

The differences between these two political systems lie, I will argue, in how far afield they are willing to go in these efforts, that is, how large a group they will recognize as included within their family. Conservatives view the family/society metaphor almost literally; their vision of society is most comfortable with the family and the local community. They extend it beyond this only with great reluctance. Liberals, in contrast, are quite willing to embrace much larger social organizations, ultimately recognizing a world community.

To understand this, we need only return to the evolutionary view that Lakoff has mined. Human groups and societies have evolved enormously in the tens of thousands of years our species has been in existence, and particularly in the past few thousand years. As I just noted, the first, smallest and simplest group to evolve, one that appeared long before our own species did, was the family. Human families, and those of some other species, particularly some non-human primates, then associated together into larger groups, usually called tribes. The rest of human history can then be described in terms of the development of progressively larger and more complex societies, culminating today in massively populated nations, and even beyond those, an emerging world community.

Conservatives, as we saw earlier, prefer stability, the absence or minimization of change. It is to be expected, then, that they would tend to identify most strongly with the earliest—longest-enduring, most traditional—groups. These include primarily the family and what might be considered the descendant or modern equivalent of primitive tribes, the local community. Liberals, being more open to and accepting of novelty and change, more comfortably associate themselves with the most recently formed—and still very much evolving--social organizations, the nation and increasingly the entire planet.

We can now understand one reason why Haidt believes that conservatives are more group-oriented than liberals. The relatively small, simple social organizations that conservatives are most comfortable with are usually more cohesive and more intimate than large national or international societies. Membership in them is more immediate and obvious. Being a citizen of a nation, or a member of some national organization, does not seem to bond people closely in the way that families and traditional local communities do.

But the latter are in fact groups, and if we view liberals and conservatives in terms of these differing group orientations, many of the differences between them become readily understandable. Consider the examples I mentioned earlier. Liberals respect authority when it emanates—as it does in the case of political correctness and federal regulations—from the national government, or some other group that exists on a national level. Likewise, liberals exhibit loyalty to groups—such as labor unions, or Occupy Wall Street—that extend far beyond any local community, which are in effect national or even international organizations. The environment that liberals increasingly view as sacred is also a truly international society, one composed of not only people but all other species, on the entire planet.

Conversely, when conservatives express these same values, they do so in the context of much smaller groups. A strong police force exerts authority that is limited to a local community. Conservatives favor relatively harsh laws against not only serious crimes like murder, burglary, theft and assault, but also against victimless crimes, like prostitution and drug use, because these forms of behavior, too, are perceived to threaten the fabric of the family and local community. Conservatives show much less interest in laws against behavior that affects larger social organizations, such as corporate crimes and environmental pollution.

Conservatives likewise show greatest respect or loyalty towards the family and the local community, and much less for the national government (as when they oppose higher taxes or governmental regulations). They regard heterosexual marriage as sacred, generally strongly opposing gay marriage or civil unions. Religion, for conservatives, is traditionally a local affair, involving attendance at a neighborhood church.

From this perspective, then, that old political bromide, “everyone wants the same things”, has some truth. Liberals and conservatives do want the same things for society. Where they differ is in their vision of society—the kind of social organization they most naturally align themselves with. Conservatives prefer it to be small and simple, liberals embrace the large and complex.

Plus ca Change, Plus c'est la Meme Chose

While liberals and conservatives differ in the type of group they favor, we have also seen that each can favor change or growth in some circumstances, but stability in others. Growth and stability are generally opposing forces. In any particular situation, either one or the other is favored. What determines which is favored in any particular circumstance, and how is that related to one's political orientation?

The holy trinity of life. To answer this question, we first need to recognize a third major drive that is fundamental to all living things: reproduction. Together with growth and stability or self-maintenance, reproduction makes up a triumvirate of attributes that goes a long way to describing what makes life unique. Consult any biology textbook, and you most likely will find living things defined primarily by their ability to grow, reproduce and maintain themselves.

These three properties are exhibited by cells, by organisms, and by societies of organisms. Let's start with reproduction, the basis of all families. A family is created when two individuals reproduce themselves. As the individuals continue to reproduce, the family grows in size, adding new members. Thus both phenomena, reproduction and growth, are occurring simultaneously.

In the time of our ancestors, who lived in small tribes or communities composed of families, growth was largely measured by an increase in population. Families grew by having more children. Tribes grew by having more families. Consequently, an individual or family's wealth was largely determined by how many children they had. A tribe's wealth or power, likewise, was determined by how many families they included.

In these circumstances, reproduction and growth are basically the same phenomenon. Whether we call it one or the other depends on our perspective. From the perspective of the individual, reproduction is occurring. But from the perspective of the family, growth is occurring.

This same relationship between reproduction and growth occurs at higher levels of social organization as well. How do families reproduce themselves? Their children mature, leave the family, and start their own families. The result is the growth of the tribe or community. A tribe, in turn, might effectively reproduce itself when one or more families split away, forming their own tribe.

So we can formulate a basic social principle that relates growth and reproduction as it largely took place at this time: reproduction at one level of existence constitutes growth on a higher level of existence. Another way of putting this is to say that growth of groups on one social level occurs through an increase in number, rather than size, of groups (or individuals) on the level below them. Families grow larger not by having larger children, but by having more of them. Tribes grow larger primarily not by having larger families, but more of them. Growth of a larger society, at this early time, resulted not from larger communities, but more of them.

What about the third major drive or property of living things, stability or self-maintenance? Let's return to the family, and consider growth on the individual level. As children mature, they become less dependent on their parents, more capable of contributing to the family's needs, eventually taking over many of the roles of their parents as the latter grew older. In other words, the growth of the young balances the decline of the old; new blood replaces the original. In this manner, the growth of individuals stabilizes the family.

The same relationship exists on the next level; growth of families stabilizes the tribe. Families grow by having more children, and they replace older members of the tribe who die. On a still higher level, a larger society composed of multiple tribes or communities, the growth of tribes stabilizes the society.

Now a second basic social principle emerges: growth at one level of existence constitutes self-maintenance on a higher level of existence. Another way of looking at this is to say that when groups reach a certain size, they stop growing and began to multiply, or proliferate. This process begins with the family. When children mature, they leave the family and form new families of their own. Along with the aging of the parents, who eventually are unable to reproduce further, this has the effect of preventing families from growing too large; the excess growth, or size, is diverted into forming new families, or number (which is size on a higher level). Likewise, when tribes reach a certain size—that is, number of families—one or more of these families is likely to leave, forming a new tribe.

We can summarize these two principles in force at this time by saying that reproduction on one level of existence is growth on the next higher level of existence, and is self-maintenance on a still higher level of existence. All three processes normally occur on every level. Individuals grow, reproduce and maintain themselves. So do or can families, tribes or local communities and societies. But any one of these processes, on a particular level, is another one of these processes from the perspective of a different level.

We all have many families. These simple relationships I have just described still exist to some extent in modern societies. But they are greatly complicated by a number of other factors. Two in particular are highly relevant to our understanding of political views.

First, modern societies are far larger and more complex than those of our ancestors. We still have a social system that includes a nested hierarchy, of families, local communities, and larger societies such as the nation. But our relationships to these original groups is somewhat different, and in addition, there are many other kinds of groups present today.

Consider first our relationship to families, local communities and the national society. Our ancestors generally had their most direct relationships with family members. Their relationships with members of the tribe outside their family were more indirect, mediated by their family; that is, two such individuals did not relate to each other as independent individuals, but as members of distinct families. Similarly, if a member of one tribe related to a member of another tribe, this was mediated first by their membership in a particular family, and second as a member of a particular tribe. The higher in the social organization one went, the more indirect the relationship was, that is, the more intervening groups mediating it.

These relationships are preserved to some extent today. For example, as a member of a family, we may be subjected to local ordinances involving property, schools and taxes that impact family units directly, and the individuals within the family only indirectly. We may further be subject to federal laws and regulations that directly affect the community, and only indirectly affect us through a chain of relationships involving the community and the family. The same may be true of our relationship with non-governmental organizations, such as businesses. We may interact indirectly with the local branch of some business through the family, and still more indirectly through the local branch with the national organization.

But in addition to these hierarchical relationships, we all have more direct relationships with higher social levels. For example, when we pay income tax, we are interacting directly with the federal government, as individuals independent of families (except, of course, for married couples filing jointly or with dependents), and the local community. Likewise, some of the laws we must obey are federal, rather than local. We also may interact directly with non-governmental organizations such as businesses, as both consumers and employees, and again, these interactions may occur at levels well beyond the community.

A second major difference in the structure of modern social systems is that we are all members of groups at various levels that exist outside of the family, the local community, and sometimes higher levels. A few examples of such groups existed among our ancestors. For example, when men in a tribe went on a hunting party, they formed a group that was independent of any family. But today we have taken this concept to a vastly greater degree. Anyone can create a group centered around some activity or interest, and recruit others to join it, and such groups may exist at local, national or even international levels. Thanks to the internet, many of these groups are composed of individuals who have never met any of the other members face-to-face.

To add to the complexity, there is enormous overlap among these groups. An individual can be a member of several different groups simultaneously, and in each group may have a different relationship to larger social organizations. Thus as member of a local group, an individual may interact through that group with a larger society, just as members of a local community do. But as a member of a national organization that same individual may directly interact with that much larger society.

Finally, there is another kind of group, or what I would call quasi-group, that plays a critical role in modern societies. This is composed of individuals who have some shared characteristic that distinguishes them from other individuals. For example, minorities, such as women, African-Americans, and gays, each form a distinctive kind of group. So do people below a certain minimum income level, as well as individuals with a physical handicap. We generally refer to groups like these as classes.

Classes are like groups in that they form a fairly well-defined sub-set of the population that can be treated in some situations as different from other groups. But they are more like individuals in that their members are generally not organized around any common goal or purpose. People usually have no choice about what classes they belong to and may not even consider themselves members of a class. And membership in many cases is somewhat arbitrarily defined, as for example, when we say that the poor comprise a class. As we will see, being able to view classes as both individuals and groups is important in understanding the liberal perspective.

Despite this complex web of social relationships, the basic relationship that I described earlier still holds to some extent. Specifically, most of these other groups are capable of reproduction, growth and self-maintenance, in somewhat the same manner as these processes occur within the traditional groups. However, at the level of individuals, reproduction in these newer kind of groups is generally through social processes—recruitment of new members—rather than biological ones. And because individuals may directly join larger societies, the relationships of reproduction, growth and self-maintenance may in effect skip some of the stages they traditionally play out in.

The pill that makes you larger. The second major difference between modern societies and earlier ones is the prominence today of economic growth. As I noted earlier, growth of ancient societies was mostly determined by population. Human beings, and the manual labor they performed, were the ultimate resources.

As time went on, and these early tribes and societies became somewhat larger and more complex, economic growth became more important, but it did not at first disturb the basic relationship between growth and stability. This is because initially population growth and economic growth were closely correlated. If a family had more economic wealth, it could support more children. If a tribe had more economic wealth, it could support more families. If a larger society had more economic wealth, it could support more tribes.

In other words, most of the increased wealth went towards subsistence, to sustaining more people. Just as growth in families replaced the individuals dying out in the tribe, the growth in economic wealth replaced the wealth consumed. So economic growth implied more population growth, but this population was, as before, distributed in families, tribes and larger societies, in each case balanced against deaths and other factors reducing the population.

For a number of reasons, which are beyond the scope of this discussion, this close relationship between population growth and economic growth eventually began to break down. While it still exists to some extent in some places under some circumstances, it is generally not the case in America. For most of our history, economic growth, by various measures, has outstripped population growth. Indeed, economic growth is often defined as wealth or income per capita, conceptually divorcing it completely from population growth. In any case, when politicians of any stripe talk about growth, they are not referring to just population growth, though that may accompany economic growth.

How does economic growth affect the relationships between reproduction, growth and self-maintenance? The issue is complex, and a full discussion of it beyond the scope of this article. But I need to make a few key points. Economic growth can be viewed as the production of material objects, or even of services, which can be reproduced, and therefore grow in number.[2] These products and services may exhibit turnover—that is, products may wear out, or become obsolete, while a service generally is complete within a certain period of time—that is somewhat analogous to death of individuals. So in principle, the same relationships between reproduction, growth and self-maintenance that we saw with populations are possible for economic goods.

A major difference between economic growth and population growth, however, is that the former does not result in the formation of hierarchical groups. As discussed earlier, families are limited in their growth by the reproductive lifetimes of the parents, and further by the fact that when children mature, they leave the family and begin their own families. Likewise, at higher levels of social organization, subgroups tend to split off from larger groups, limiting the growth of the latter and starting a new larger group. The result is that growth at any level tends to be limited or constrained, with much of the increased growth going towards formation of a higher level. Further balance is provided by the fact that people of course die, so that some growth simply replaces this death. As discussed earlier, this is how growth at one level manifests as stability at a higher level.

These dynamics do not necessarily play out with economic growth. This is because there is basically no limit to how much material wealth an individual, a family, or a local community can accumulate. This means that growth at one level, rather than manifesting itself as stabilization at a higher level, may simply be more growth at that level.

For example, suppose a new industry moves into a community, and as a result, many of the families in that community get higher-paying jobs and become wealthier. This economic wealth, unlike the traditional wealth of families—children--does not split off and form new sources of wealth. While some or all of it may eventually be passed on to the children, much of it simply accumulates in the families. So much of the wealth in the community grows not through an increase in the number of families, but by an increase in the wealth of the families. In other words, growth at one level is also growth at higher levels.

This means that economic growth is potentially a highly destabilizing force in societies, and this creates a lot of the conflict in political debate and dialogue. Traditionally, conservatives have tended to be far more pro-growth than liberals. Yet conservatives also favor stability, while liberals favor growth and change. So each side tends to be inconsistent in its view of growth. We will examine this inconsistency in a little more detail later.

However, this is not the end of the story. While I said that economic growth can accumulate indefinitely in individuals and families, there is another force that strongly opposes this tendency, or more precisely, opposes the effects of this tendency. As economic growth proceeds, the social environment is transformed. What is at first a luxury becomes a necessity. Thus as we all know, it's very difficult for individuals or families to survive in modern societies without such relatively recent innovations as telephones, television, cars, computers, internet connections, and other electronic products and services that are growing almost daily. At one point, all of these inventions were just toys that only the wealthiest could afford. Now they are taken for granted; they have become necessities almost as much as the traditional food, clothing, and shelter. The same is true in other areas of technological advance, for example, health care.

This transformation has the effect of discounting or nullifying much economic growth. It is the human social equivalent of what evolutionary biologists refer to as the Red Queen hypothesis, where evolution is understood not to make organisms more complex or better able to adapt to their environment, but simply to maintain their original place in an environment that is continually growing more challenging (van Valen 1973). This creates a stabilizing force. Let me try to explain this by expanding on the Alice-in-Wonderland metaphor.

Imagine an early society in which individuals were able to grow to a much larger size than normal, indefinitely. Instead of five feet tall, as our ancestors might have been at that time, they grew to ten feet, then fifteen, then twenty. This would have the effect of enabling families to grow larger not simply through having more children, but having larger ones. And likewise, a tribe composed of such families would grow through the increased size of these individuals as well. Certainly this larger size, assuming it could be sustained, would have provided our species with much greater power in their relationships with the environment.

Now suppose, though, that everything else in the environment around these societies also grew larger. Animals became larger. Trees and other plants became larger. Bodies of water became larger. If the entire natural environment scaled up in this manner as fast and as much as body size of humans did, there would be no new advantage to human growth. The dynamics of growth would be just as they had been before, when growth of social systems occurred primarily through greater numbers, achieved by reproduction.

My claim is that economic growth is often something like this. While we scale ourselves up, we also scale up the social environment in which we live. In an important sense, we still recognize that growth has occurred; we regard ourselves as “larger” than members of previous generations were. Any economist will agree that America is a wealthier country than it was half a century ago. It has become a matter of faith, for both parties, that each generation should be better off than the previous, and if it isn't (as many argue is the case today), there is a serious problem.

But individual perception of growth or well-being is not based entirely on comparisons with individuals of the past, which for most of us is limited to our parents and possibly to our grandparents. It's based to a large extent on comparisons to the here and now. Consider the scenario I mentioned earlier, when an industry moves into a community and many families become wealthier. I noted that the community may also grow wealthier as a result. But the greater community wealth brings changes with it. Homes become more expensive, partly perhaps because they are larger and better built and furnished, but also because land values have appreciated. The local schools are upgraded, able to hire better teachers and build more modern facilities. Local services like the police force are upgraded or enlarged. Upscale new businesses move in to take advantage of the wealthier clientele. Amenities like parks, golf courses and so on may be developed. And so on.

In order to live in a community like this, to take advantage of its increased wealth, an individual or family has to be wealthier. So much of economic growth at the level of the family becomes self-maintenance at the level of the community. One could of course move to a less wealthy community, and often that is what people do, but if all communities are growing economically, this option effectively becomes closed off. Also, a less wealthy community is likely to have less high paying jobs available.

In summary, while economic growth is potentially disruptive to the traditional, natural relationships between reproduction, growth and self-maintenance, frequently it's possible to view it in a manner in which it doesn't really change these relationships. This should become clearer in the following discussion, where we will see that in many cases growth at one level can be understood as self-maintenance at a higher level. In those instances where the relationship is not so clear, on the other hand, we can see the complicating effects of economic growth.

Two Sides of Different Coins

We are now in a position to reconcile the very widely assumed notion that liberals and conservatives differ on their view of change vs. stability, on the one hand, with the evidence that both can favor either change or stability, under certain circumstances. As we have just seen, growth at one level of existence can often be understood to be the same process as self-maintenance at a higher level. It follows that there is generally no way to advocate one of these processes without advocating the other at another level. What primarily distinguishes the liberal and conservative viewpoints is that liberals emphasize the perspective from which growth is promoted, while conservatives emphasize the perspective from which stability is enhanced.

Thus conservatives usually emphasize the upper level of the stability/growth dynamic, which is always a group of some sort; this is probably another reason why researchers like Haidt conclude that groups are more important to conservatives. Conversely, liberals focus on the lower half of this dynamic, which—for the large societies they identify with--generally involves classes of individuals. In this sense, liberals are indeed more oriented towards individuals. There are some important exceptions to this, but first let's look at the support for this conclusion.

Consider the so-called group modules, what I call group-stabilizing modules: authority, loyalty, and sanctity. As discussed earlier, conservatives understand these values in terms of families or local communities. These are the groups that these values are intended to stabilize. Thus local police forces and strict laws against crime are intended to guarantee the integrity of families and local communities, by preventing forms of behavior that are disruptive to these groups. Conservative sanctity towards marriage obviously promotes stability of the family, making it less likely that it will break up.

All of these values, however, can also be understood to promote growth of the group, or in some cases, individuals on the level below. A family stabilized by marriage, other things being equal, generally facilitates the development of children, that is, makes it easier for them to learn to get along with others. A community stabilized by law and order is one in which families have the space and the resources to grow, both in size and economically. In fact, the relationships are mutually interacting. It's not so much that stability at a higher level promotes growth at a lower level. It's that either one presupposes the other. One could just as well say, for example, that a family whose individual members are growing is more likely to remain stable. Individual growth, within the context of a group, means developing the kind of behavior that allows individuals to form cohesive bonds with each other.[3] To repeat, they are really the same process, simply viewed from different perspectives.

When conservatives advocate these policies, though, they generally emphasize their effect in stabilizing the group, rather than on stimulating growth of individuals or of smaller groups. Thus conservatives support a strong police force and strict laws against crime because these promote law and order, which is just a handy phrase that means stability of the community. They usually do not rationalize these policies by pointing out that they increase the growth of families. Likewise, when conservatives defend the sanctity of marriage, it is largely for the sake of the stability of the family, rather than because it promotes growth of the individual members of the family.

What about liberals? We have seen that they identify more strongly with larger, more complex societies, and accordingly, the values of authority, loyalty and sanctitity that they express are directed to stabilization of these societies. Two examples of liberal authority I mentioned earlier, federal regulations and political correctness, each have the effect of providing more or less universal rules for everyone in society, so that relationships will be smoother, more predictable. Loyalty to labor unions, another example discussed previously, stabilizes these organizations, making them capable of presenting a united front to management. Liberal sanctity towards the environment expresses the desire to stabilize the natural world, at the national or international level.

Again, though, these same values can be understood as promoting growth at the level below, which, I emphasize again, is usually the individual—or more precisely, some class of individuals. Political correctness, for example, is intended to remove obstacles to individuals advancing in the workplace and other areas of life, allowing them to lead more economically fulfilling lives. Federal regulations are designed to protect the health and safety of individuals. Loyalty towards large organizations like labor unions allows them to promote the growth of their individual workers, by agitating for greater income, safer working conditions, and so on. Sanctity towards the environment is associated with changes in individual lifestyles.

Now notice that liberals fairly consistently emphasize the growth-promoting effects of these policies, which is to say, their effects on classes of individuals. When attempting to enforce political correctness, liberals harp on the fact that certain individuals are being treated unfairly, differently from the way others are treated—rather than on the stabilization of society that a standardized set of rules of civility may have. Likewise federal health and safety regulations are rationalized by the protection they offer individuals, not the stabilization of society that results from having uniform standards. When defending the right of workers to organize into unions, liberals emphasize the benefits these unions have on these individual workers, rather than on the need for unity in confronting management. When they express sanctity towards the environment, they tout the benefits to individuals—clean air and water, the beauty of national parks, preservation of natural resources—though there is also considerable emphasis on understanding the need for the earth to find a balance. I will discuss this latter point later.

So the conservative and liberal view of group-stability values are consistent with what we might expect. Conservatives apply them to relatively small groups like the family and local community, and they view them from the perspective of their stabilizing effect on these groups. Liberals apply them to large, complex social organizations, and they view them from the perspective of their growth-promoting effects, which generally occur on the level of individuals or of classes of individuals.[4]

It's also illuminating to consider how each side views the other's policies. Liberals tend to regard strong police forces and harsh penalties for crime as oppressive to individuals. This is because they are taking the perspective not of local community/family, but of large society/class of individuals, and from this point of view, they see primarily the punitive effects on classes of individuals—the poor, the uneducated, minorities-- who are most likely to commit crimes. Conservatives, of course, refer to this as being soft on crime, as caring more about the criminal than the victim.

Conversely, conservatives regard political correctness as threatening to local communities, because they are taking the perspective not of large society/class of individuals, but of local community/family, and from this perspective they see behavior that is disruptive to traditional community behavior. For example, to regard women or gays as full citizens in every respect equal to straight males threatens the sanctity of marriage. Liberals refer to this as being bigoted.

What about the individual or group-growth modules: liberty, care and fairness? The conservative view of these values, again, is at the level of the family or local community. Free markets are intended to promote the growth of individuals and families, by allowing them to accumulate more material wealth. Lowering taxes, of course, has a similar goal, allowing individuals and families to keep more of what they earn. Removing federal regulations, in the eyes of conservatives, also promotes growth of individuals and families, by allowing them to function in their homes, in their businesses and in other areas of life with minimum interference from others.

But at higher levels, including the nation, these same values can promote group stability. Growth of families can stabilize the community, as we have seen, by in effect allowing them to integrate with the transformed social environment brought about by economic growth. In the same way, growth of communities may stabilize a larger, national society.

So from which perspective do conservatives view these values? In this case, the answer may not be immediately clear. Conservatives certainly emphasize growth to a large extent when they advocate free markets and other policies. They also like to sing praises to the greater freedom individuals have in an environment without the “burden” of high taxes and numerous regulations. But conservatives also emphasize the importance of maintaining a stable economic order. The fact that many (though by no means all) conservatives supported a federal bailout of major banks is an indication that, when push comes to shove, they often value stability over the consequences of the free market. For the same reason, conservatives often advocate federal policies that protect businesses.

If there is not a clear-cut preference here, there are two important reasons for this. First, as I discussed earlier, economic growth at the family or local community level may sometimes be manifested as growth at higher levels. To the extent this happens, the conservative has no choice but to support growth, but to emphasize its effect on the smaller groups. Second, even when growth at the lower level does manifest as stability at the higher level, the conservative is forced to choose between two preferences: the small and the stable. Thus it is perhaps not surprising that there is not a clear emphasis on one or the other. I will discuss the issue of economic growth further at the end of this section and also in a later section.

For liberals, in contrast, these same growth modules operate at the level of larger societies, particularly, again, among classes of individuals. A good example of individual liberty championed by liberals is civil rights. Liberals much more than conservatives have pushed for equal recognition of minorities, such as women, African-Americans, gays, and most recently, illegal immigrants. In each instance, they are promoting the growth of a particular social class, and in this sense this policy can be understood as affecting growth of groups.[5] Social welfare, a liberal example of care, and higher taxes on the rich, justified as being more fair, also promote the growth of a class, in this case the poor or moderately well off.

Again, all of these policies can be understood as stabilizing groups on a higher level, including the national society. Granting civil rights to minorities takes idle or discontented individuals off the streets, injecting their energy and talents into the workplace. Social welfare, at a minimum, gives individuals enough money to become consumers, helping to stabilize or even increase economic growth, and some welfare programs manage to put people back to work. Tilting the balance of taxes paid towards the wealthy is another way by which liberals boost consumerism in the economy, the argument being that essentially all the income of the poor goes to immediate consumption, whereas most of that of the wealthy does not.

In promoting these policies, however, liberals consistently emphasize the growth-promoting side of these relationships, which occur at the level of the individual or class of individual. When they advocate civil rights, it's because of the increased economic opportunities for individuals, rather than the greater contributions these individuals can make to society. When they promote social welfare, it's for the benefit of needy individuals, not because a large poor population is disruptive to society. When liberals seek higher taxes on the rich, it's likewise to ease the burden on the poor, not because greater income equality makes for a more stable society.

Again, it's useful to consider how each side views the other. Liberals tend to oppose free markets, because from the point of view large society/classes of individuals, these markets discriminate against individuals who lack the resources, background or talent to take advantage of them. Conservatives have historically been slow to recognize minorities, because from the perspective of local community/family, they find them strange and out of place in the local order.

I want to emphasize that these relationships are not rigid. I'm not arguing that conservatives are completely blind to the growth-promoting effects of the policies they advocate, nor that liberals are ignorant of the effects of their policies on social stability. As I pointed out earlier, conservatives do rationalize free markets in large part by arguing that they promote growth, and they often speak of the greater freedom individuals have in an environment with less interference by the federal government. Likewise, liberals will sometimes argue that providing opportunities for minorities strengthens our institutions (as when women were admitted into positions of political and economic power, as well as in the armed forces), and that eradicating poverty reduces crime.

I believe, though, they do this in large part in order to respond to each other. Conservatives emphasize that free markets will increase growth, as a way of appealing to the economically poorer off who tend to vote liberal. Liberals emphasize that social changes will reduce crime to placate law-and-order conservatives. In addition to these factors, there are others. There has always been a strong streak of individualism in America—immortalized in such slogans as “give me liberty or give me death” “live free or die” “all men are created equal”-- such that probably no conservative politician would rationalize any position sheerly in terms of its benefits to groups, at least not groups beyond the family level. There are still other issues that I will put off discussing until later.

Individual Groups and Collective Individuals

I said earlier that a closer examination of the views of liberals and conservatives may make it easier for each group to appeal to, or at least understand, the other. We saw that a summary of studies of the brains of liberals and conservatives concluded that conservatives are more sensitive to views that make an impact on the personal and emotional level, whereas liberals tend to be more comfortable with more abstract and intellectual reasoning. We can now appreciate that this difference is closely associated with their different preferences for social groups. Because conservatives identify more strongly with smaller, simpler groups, which have fewer members in more intimate relationships, it would be expected they would be more sensitive to the effects of their policies on specific individuals.

For the same reason, conservatives often change their positions on issues on the basis of personal experience. The late William F. Buckley, often considered the founder of modern American conservatism, came to view both gays and AIDS differently when he discovered his long-time friend and fellow conservative Roy Cohn was gay and had contracted the disease. Former Vice-President Dick Cheney, a hard-line conservative, supports gay marriage, an unlikely position that is undoubtedly the result of having a gay daughter. Former First Lady Nancy Reagan and Senator Orrin Hatch, both staunch conservatives who originally opposed stem cell research on the grounds that it violated the sanctity of the human fetus, became vocal supporters of it as a result of personal experiences with people with terminal illnesses (in Reagan's case, of course, her husband) that might some day be cured by this research.

Liberals, in contrast, we have seen are more concerned with classes of people than specific individuals. Indeed, the very presumption that there are social classes—that we can group otherwise diverse, unrelated people according to their gender, sexual orientation, economic well-being, ethnic origins, cultural backgrounds, or some other single common feature—is largely a liberal idea. The liberal identification with large social organizations makes them especially sensitive to classes, because the latter are a major component or sub-group these kinds of groups. Grouping people in classes is one major way in which they can be viewed as more or less directly related to the large society, without the mediation of further groups.

So when liberals advocate growth modules such as liberty, care and fairness, while these are directed towards individuals, they are not directed towards specific individuals. They are referring to a very large class of people—the poor, the unhealthy, women, African-Americans, gays, and so on. Liberal empathy is for the individual in the sense that it is genuinely concerned with all aspects of the lives of these people, not just those associated with their membership in this group or class. But it is nonetheless non-personal in that it is concerned with very large numbers of such individuals, none of whom are or can be distinguished clearly from any of the others. Indeed, liberals are sometimes caricatured by conservatives as loving all humankind, but detesting every Tom, Dick and Harry.

Because of the abstract way in which they view individuals, liberals are much more likely to be persuaded by intellectual arguments, rather than by personal experience. Most colleges and universities in America are hotbeds of liberalism. It flourishes on them in large part not only because students are taught to think rationally and rigorously, making use of all available sources of information, but also because of the ivory tower effect—college campuses, and the professors and students on them, tend to be isolated from the real world—which is to say, personal--consequences of any particular political policy

Size Matters

The differences outlined here may also provide some important insight into what is surely the most frustrating aspect of most political arguments: how liberals and conservatives can consider one specific proposed policy, and come to such diametrically opposed predictions about its outcome. As an example, let's consider what looms as the single most important and divisive issue in the current Presidential campaign: the massive federal debt. The conservative solution to the problem is to reduce taxes, and also to eliminate many federal regulations, actions which they argue will stimulate growth. Liberals believe that a massive government stimulus, that is, injection of further borrowed money into the economy—basically, a form of social welfare—will be more effective in getting the economy to grow. It is no exaggeration to say that the winner of this year's Presidential election will almost certainly be determined in large part by which of these scenarios proves more persuasive to the voters. I will not take sides on this complex issue here, but rather am interested in exploring why the perceptions of the two parties are so different.

Conservatives, because they identify most strongly with relatively small, simple groups like families and social communities, tend to view the effects of policies from the perspective of this level. Specifically, in small groups, the consequences of actions tend to be fairly predictable, proceeding by a simple chain of cause and effect. So if you reduce taxes that a particular individual pays, that individual will have more money to spend. If she is a small business owner, she will have more money to put into expanding or upgrading her products and services. As a consumer, she will spend more on consumption, therefore stimulating more production of goods and services by other businesses. Likewise, if the number of federal regulations on businesses is reduced, this will also save them money. In addition, it will accelerate and streamline production, by avoiding delays and extra efforts that compliance with regulations frequently requires.

The liberal perspective, made from the vantage point of a much larger and more complex society, sees a more complicated scenario. For one thing, many people work for the government, directly or indirectly, at various levels. Many other people work in private industries that depend to some extent on federally-funded programs, for example, those supporting research. Lowering taxes therefore generally requires cutting some jobs, salaries, goods and services, which means there will be reduced consumption, resulting in contraction of businesses. Our tax dollars also support the nation's infrastructure—roads, bridges, public utilities, and so on. Lower taxes may result in a reduction in needed growth or maintenance of this infrastructure, which negatively impacts virtually all economic activity.

The effects of reducing federal regulations are also complicated. These regulations are designed to protect the health and safety of workers and of the general public. Relaxation of these regulations therefore may prove to be costly economically, not to mention in human lives. Some of these costs accumulate gradually, as when air or water pollution is discovered to increase health risks in a community. Some may arrive suddenly and dramatically, as when a gas pipeline here in the Bay Area exploded about two years ago, killing several people and destroying part of a neighborhood. But it is at the very least clear that regulations cannot be reduced or minimized without costs of some sort.

Again, I don't want to oversimplify. Conservative economists are not dummies. They are not unaware of the vast network of relationships that underpin modern economies. But at the very least, the different liberal and conservative preferences bias each towards very different predictions of the outcome of a particular set of policies. Different factors are given different weights or priorities. How much difference this can make will become even clearer when we explore these differences a little further.

The Law of Power

In addition to favoring lower taxes in general, conservatives usually also favor a lower tax differential between the wealthy and the rest of the population; in other words, they think the tax rates of the wealthy should be lowered to values closer to those of the less wealthy. One of their main arguments is that the wealthy are the source of most investment and business startups, and that taxing them higher will thus discourage innovation. In addition, conservatives may sometimes argue that higher taxes on the rich are unfair, in effect penalizing them for being more successful, though this individual perspective is less prominent. Liberals have exactly the opposite view, believing that it is fairer to tax the wealthy more, in effect transferring some of their wealth to people who are more in need.

The conservative view is based on the notion that individuals act more or less independently, so that what they earn is a result of their efforts alone. This belief is highly dependent on a vision of small, fairly intimate groups, where the roles, responsibilities and contributions of each individual are fairly clear-cut. In these relatively simple situations, what each individual produces is or may be fairly strongly correlated with the extent of his efforts.

In large complex societies, the liberal argues, this is not the case. The enormous interdependencies at play make it essentially impossible to assign any contribution or result entirely to a particular individual. We all make use of the effort of others. All of us, for example, benefit from a public school education, and as I noted earlier, a publicly funded infrastructure of roads, communication networks, public utilities, and much more. The success of workers in one private business also depends on the success of workers in other businesses.

It's not just that we all depend on each other, though. It's that the dynamics of this dependency strongly implies vast inequalities in wealth. Studies of the U.S. and some other advanced societies have found that wealth is distributed according to an exponential or power-law (Levy and Solomon 1997; Moss et al. 1999; Dragulescu and Yakovenko, 2001; Sinha 2006). For example, instead of half of the wealth being held by half of the population, as would be the case if wealth were randomly distributed, it is held by half raised to some power, such as one-quarter, one-eighth or one-sixteenth of the population, or some other small fraction, depending on the society. In other words, much of it is highly concentrated in a relatively few individuals.

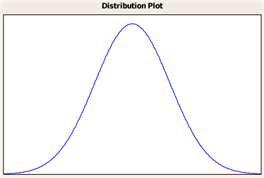

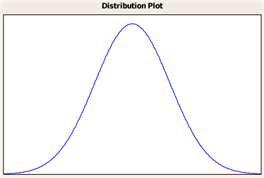

Why do such inequalities develop? The traditional American view is that people succeed because of intelligence, ambition and hard work, admittedly often along with a little luck. But the enormous inequalities in wealth that we see in America can't be explained by individual differences in factors like these, because they are generally normally distributed in the population. A normal or Gaussian distribution takes the form of the familiar Bell curve, with most individuals somewhere near the mean, and relatively few individuals far above or far below the mean (Fig. 1, upper). While this results in significant differences among individuals, these differences are not extreme. One need only consider a commonly-cited example of a quality normally distributed, height in males. The tallest man on earth is perhaps a little more than twice the height of the shortest, and no more than 20-30% taller than the mean height.

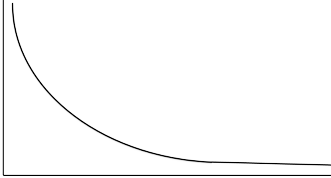

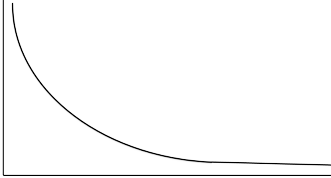

Figure 1. Normal or Gaussian distribution (upper graph); exponential or power-law distribution (lower graph). In each curve, the vertical axis represents number of individuals, while the horizontal axis represents some value that is being measured for each individual (e.g., height, intelligence, income, economic assets, etc.)

In a power-law curve, in contrast, most individuals have a fairly low value (of whatever is being compared), but there is a very long tail, meaning that a few individuals exist with vastly higher values, much higher than those found in normal distributions (Fig. 1, lower). A power-law curve looks something like the upper or right-hand half of a normal curve, but in which the high end or tail has been stretched far into the distance.

What accounts for the great inequalities in wealth, then? Studies suggest that power law distributions of wealth result from analogous distributions of connectivity between individuals and businesses (Hu et al. 2007). It has been well established that most social networks in human societies, involving not only businesses, but personal relations, the internet, as well as many other social phenomena, also are governed by a power law (Barabasi 2002). That is, most people in the network have a relatively small number of links, or connections to others, while a very small number of people have an enormous number of connections. These people, or nodes in the cases of networks not involving people, are responsible for most of the traffic in these networks. They in effect form hubs that connect most of the other people or nodes. In other words, they are the center of most of the action. Whatever is flowing through the network, a far greater share of it flows to and through them.

Thus large societies seem to generate the potential for vast inequalities in connectivity that are not at all apparent in smaller societies. Connectivity, moreover, is clearly closely related to economic wealth. Within any business organization, the individuals with the most power, influence and wealth are those who are connected, via subordinates, to everyone or virtually everyone else. This is what “at the top” means in the traditional inverted pyramid scheme of business organizations. Likewise, the most successful businesses are those that have the most links to suppliers, to collaborators, and to markets and consumers. The more such links, the more power and influence they have, and the more potential for generating wealth.

To summarize, the conservative's view of individuals and their groups is based on a much simpler model than is the liberal's. The conservative view, born out of the experience all of us have in small groups like families, is that we act freely and are ultimately responsible for the consequences of our own actions. This view is the one that most of us are personally probably most comfortable with, which goes some way to explaining the substantial appeal of the conservative view today. The liberal view, consistent with the modern scientific worldview, is that we are creatures of contingency, very much a product of the conditions around us. We don't act freely; our actions are complex responses to complex causes. The analysis in terms of networks I just provided adds further details to this complexity.

Again, I am not trying to take sides here. The analysis I presented here may provide an explanation for economic inequalities, but it does not necessarily support liberal remedies over conservative ones. One might argue, as many conservatives do, that even if inequalities are inevitable, everyone is potentially better off than they were before. But at the very least, I think we must dismiss the traditional notion that there is a close relationship between individual differences and individual benefits.

I also want to add that the “individual responsibility” argument, like almost all positions in politics, is used by both sides, with little recognition by one side of the similarity of the other side's rationale. Conservatives, for example, resent social welfare, because they believe that it is giving individuals something for nothing, that they are living off the efforts of others. This is a prime example of what individual responsibility means to conservatives.

Yet liberals make an analogous argument when they argue that individuals need to make efforts on behalf of the environment—driving cars less, recycling, consuming less—for the sake of the environment. This is what liberals mean by individual responsibility. And just as conservatives think people should work for their material benefits, even if society could give them these benefits free, so liberals believe people should make efforts to reduce their impact on the environment, even if technological solutions could obviate this.

The reason each side has difficulty seeing its view reflected in the other is because the conservative argument is based on our membership in small groups, while the liberal argument is based on our membership in national and international societies. The conservative sees that abdicating responsibility is damaging to the cohesion of the small group. The liberal sees that abdicating responsibility is damaging to the cohesion of the large society.

Why aren't Conservatives Conservationists?