|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Andrew P. Smith, who has a background in molecular biology, neuroscience and pharmacology, is author of e-books Worlds within Worlds and the novel Noosphere II, which are both available online. He has recently self-published "The Dimensions of Experience: A Natural History of Consciousness" (Xlibris, 2008). Andrew P. Smith, who has a background in molecular biology, neuroscience and pharmacology, is author of e-books Worlds within Worlds and the novel Noosphere II, which are both available online. He has recently self-published "The Dimensions of Experience: A Natural History of Consciousness" (Xlibris, 2008). SEE MORE ESSAYS WRITTEN BY ANDY SMITH AN IMP RUNS AMOKThe Promise and the Problems of

|

| Zone | Location in four quadrant model | Type of approach |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Inside of individual interior | Phenomenology |

| 2 | Outside of individual interior | Structuralism |

| 3 | Inside of social interior | Hermeneutics |

| 4 | Outside of social interior | Ethnomethodology |

| 5 | Inside of individual exterior | Cognitive science |

| 6 | Outside of individual exterior | Empiricism |

| 7 | Inside of social exterior | Social autopoiesis |

| 8 | Outside of social exterior | Systems theory |

Pluralism, and examples of their corresponding approaches to knowledge.

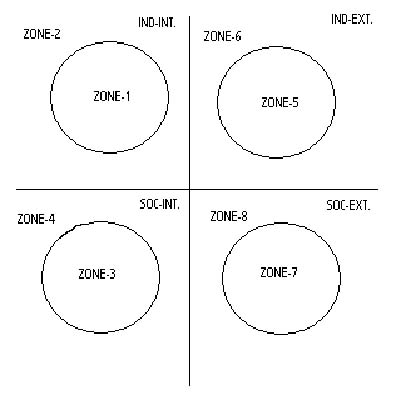

The terminology I have listed in column two of Table 1 corresponds to the zone assignments in Figure 1. However, Wilber's textual descriptions of these zones do not always correspond to the zone assignments in the figure. In fact, a little examination reveals a major inconsistency in his description of these zones.

Consider zone-5. Though it should be an inside view of an individual exterior, Wilber describes it as an “outside view of an inside view of an organism”.[9] What exactly does he mean by an “outside view of an inside view”? Is it the same thing as the inside view of an exterior or not?

To answer this question, we turn to what Wilber calls integral mathematics, which allows us to represent each of the eight fundamental perspectives as a unique product of three binary terms. Two of the terms refer to the quadrant location or position of the holon (interior/exterior; individual/social), while the third term refers to the view of the holon (inside/outside). Each term is described as either first-person (1-p) or third- person (3-p).

For example, Wilber describes zone-1 as 1-p x 1-p x 1p, that is, the inside (or first-person) view (1st term) of an interior (2nd term) of an individual (3rd term), and he designates zone-2 as 3-p x 1-p x 1p, the outside (or third-person) view of an interior of an individual. Notice that this terminology confirms the point I made in the previous section, that in IMP, the outside view of an interior is third-person. This interpretation is made even more certain by the way Wilber describes zone-2 in the text: “start with any occasion or event…then look at its individual form (a first person or 1p), then look at the interior or first-person view of that individual (1-p x 1p)…but do so from an objective, scientific or third-person stance (3-p x 1-p x 1p).”[10]

This passage I have just quoted also makes it very clear—to me, at least—that all zones in the upper, individual two quadrants should have as their final term 1p.[11] This term, unlike the first two terms, is not hyphenated, because it refers not to a view of a holon, but to the holon itself (or more precisely, an aspect of a holon). Zone-5, like zone-1, is in the upper (individual) half of the four-quadrant diagram, and since it is also an inside zone, it seems to me that only one of the three terms used to designate it should differ from zone-1.

Yet Wilber describes zone-5 as 3-p x 1-p x 3p. To be consistent, it should be designated as 1-p x 3-p x 1p, that is, the inside or first-person view of an exterior of an individual.[12] Likewise, Wilber's description of zone-6 as 3-p x 3-p x 3p is also inconsistent with the quote indicating that an individual is to be represented by 1p. It should be 3-p x 3-p x 1p.

So zones 5 and 6 are not described by Wilber in a way that is consistent with the way he describes zones 1 and 2—which is to say, not consistent with the way all these zones are defined in Fig 1. To get more insight into just what Wilber does mean by zone-5, let's examine what he presents as examples of this kind of approach. The one he emphasizes the most is the work of Maturana and Varela on frog vision. They were, he says, “simply trying to reconstruct what was available in the subjective-cognitive world of the frog, but they were still thinking about it in objective terms. It was the inside view of the frog approached objectively.”[13] Wilber also describes Maturana and Varela's approach as biological phenomenology, which is consistent with an inside view that is much like that of zone-1, which he specifically exemplifies with phenomenology. But the inside view of zone-5 differs from that of zone-1, I think Wilber intends to say, because it is largely of exteriors, for Maturana and Varela presumably did not concern themselves overmuch with what the frog was “thinking” but what it was perceiving, that is, its view of the exterior world. This is consistent with representing this approach in the right-hand, exterior quadrants.

If Wilber stopped right there, there would be no problem. (Except that he regards the individual frog—in contradiction to his earlier defining quote—as 3p rather than 1p.) But since he then adds that Maturana and Varela's approach is an outside view of this inside view, it seems to me it should be represented in zone-6, just as structuralism, an outside view of interiors, is in zone-2. Structuralism is in fact also an “outside view of an inside view”, a point I will return to shortly.

Wilber also includes in zone-5 cognitive science. Cognitive science differs from Maturana and Varela's work in that it studies humans rather than animals, but this is not a significant difference in terms of Wilber's model. It is still an individual holon being studied, just a different one. Unlike Maturana and Varela, however, cognitive scientists study not only human perceptions of the world, but also human thoughts and feelings—in other words, interiors as well as exteriors. So now we have in zone-5 not only an outside view of an inside view, but the inside view is to a large extent one that belongs in the left quadrant, not the right. In other words, cognitive science, it seems to me, belongs in zone-2 as well as in zone-6.

Wilber is of course free to define his terms as he wants, but in addition to being inconsistent with his description of other inside zones, his description of zone-5 as an outside view means that approaches in this zone do not bear the same kind of relationship to those in zone-6 as zone-1 approaches do to zone-2 approaches. Wilber points out that zone-2 or structuralist approaches are built from combining the insights of zone-1 or phenomenological approaches.[14] Thus structuralism could not even develop as a form of knowledge until phenomenology in some sense existed. Likewise, zone-6 or empirical approaches should be built from combining the insights of zone-5 approaches. This would be the case if zone-5 were an inside view of an individual exterior, that is, if it described how exteriors appear to a single individual. But empiricism is not built up from combining the insights of cognitive science, in the way that structuralism is built up from phenomenology. Empiricism in fact existed long before cognitive science was developed.

Why then does Wilber define zone-5 in the way that he does? I can only speculate, but I really think mainly because he wants to believe that his four quadrant model is genuinely comprehensive, that it is truly the “theory of everything” he has described it as. Specifically, he wants, on the one hand, to demonstrate that every major academic field of study corresponds to a particular perspective—that it can be neatly placed in one of his eight zones—and conversely, that every perspective, every one of these zones, corresponds to a major academic field of study. But the correspondence is in fact not perfect, so he in effect fudges, by redefining some of his perspectives so that they better fit the actual forms of knowledge currently in use.

To see that this is so, let's begin by considering zone-5 in the sense that it would be consistent with Wilber's description of zone-1. Just as zone-1 is an inside view of an interior of an individual, zone-5 should be an inside view of an exterior of an individual. In other words, it is the immediate experience we have of the exterior world, as contrasted with the immediate experience of our thoughts and feelings that is represented in zone-1. Does Wilber recognize this type of perspective at all? I'm not sure. He may include it in zone 1. Thus as I noted above, he describes zone 1 as “a world arising in your I-space…that…directly and immediately presents itself to your naked awareness…” That description seems to apply to our inside view of exteriors as much as our inside view of interiors.

But if Wilber means to include our inside view of exteriors in zone-1, he does so only by creating numerous problems elsewhere in his model. First, of course, this view logically should be in zone-5. Since the upper right is concerned with exteriors, any inside view of them should be in this quadrant, not in the upper left. We have already seen that Wilber represents the outside view of the inside view of exteriors in the right quadrant, so certainly the inside view itself should be there. By putting the inside view of exteriors in zone-1, he would be separating two kinds of approaches that by any logic belong in the same quadrant. Conversely, he would also be lumping together two kinds of inside experiences that can and ought to be distinguished. Our inside view of exteriors—how the exterior world presents itself to us—is not the same as our inside view of our mental events. This was a major criticism of the four-quadrant model by Goddard (2000): that it failed to distinguish between exteriors, on the one hand, and our view of them, on the other.[15]

Another problem created by putting our inside view of exteriors in zone-1 is that it leaves a gaping hole in zone-5. As IMP now stands, Wilber says zone-5 represents approaches such as cognitive science and biological phenomenology, which are, as we have seen, “an outside view of an inside view”. But if the inside view is in zone-1, then these outside views should be in zone-2, along with structuralism. We have already seen that that is partly the case, anyway, with cognitive science, since its inside view is partly one of interiors. But if the inside view of exteriors also belongs in zone-1, then all of cognitive science as well as biological phenomenology belong in zone-2, together with. structuralism. If the inside view of both is in the same zone, so must the outside view of each share a common zone.

Putting the inside view of exteriors in zone-1 also creates problems for Wilber's treatment of empiricism. He describes this as 3-p x 3-p x 3p, the “outside view of an outside view of an objective organism.” But empiricism is ultimately based on an inside view. As I noted earlier, empiricism combines the inside insights made into exteriors, just as structuralism combines the inside insights made into interiors. So if the inside view of exteriors belongs in zone-1, then empiricism, too, it seems to me, belongs in zone-2.

So if Wilber intends that zone-1 include our inside view of exteriors, his model is riddled with inconsistencies. But the only alternative open to him is to drop the outside view part and regard the inside view of exteriors as a zone-5 approach. We have already seen that he doesn't do this. But suppose he did? Then he would define zone-5 in a way consistent with his definition of zone-6. He would also at least begin to address Goddard's point that there needs to be a distinction made between exteriors and our view of them.

But there would still be inconsistencies in his model. Where would he put cognitive science and biological phenomenology? Since they are an outside view of an inside view, and since the inside view is in zone-5, they should be in zone-6. But not entirely so, particularly not cognitive science. As I pointed out earlier, cognitive science studies the inside view of interiors as well as exteriors. It is the outside view of both. So if the inside view of exteriors is in zone-5, cognitive science, as an outside view, should be in both zone-6, and also in zone-2, with structuralism. It should straddle two quadrants.

And meanwhile, what happens to empiricism? Is it a zone-6 approach? If it is, it would no longer be distinguished from cognitive science. But if it isn't, where else could it be?

All these inconsistencies are bad enough, there are numerous other problems with Wilber's IMP that deserve mention. Note that he regards zone-2, exemplified by structuralism, as an outside view of the interior of an individual. But structuralism, as he explains, is developed by putting together the insights of introspection, which is an inside view of the interior of an individual. So structuralism, like cognitive science, is really “an outside view of an inside view”, of the interior of an individual. In other words, it requires a minimum of four terms to address. The same is true of all his other outside zones, as well as of cognitive science and biological phenomenology, which as we have seen, are outside zones masquerading as inside ones. Since the approaches he gives as examples of these outside perspectives always proceed by in effect synthesizing the data obtained from the corresponding inside view, they all are an outside view of an inside view, and all require an additional term to express.

As I noted earlier (see footnote 8), Wilber cautions us that his use of integral math terms is somewhat oversimplified, and that more terms may be required than he is actually indicating. So the three term designation of structuralism as an outside view of an interior of an individual may be his convenient shorthand for an outside view of an inside view. But if that's the case, his diagram of the zones (Fig. 1) is very misleading, for then all the outside zones are more complicated than the figure indicates; there is no simple outside/symmetry involved as the figure implies. That is to say, the outside view is not outside the same phenomenon that the inside view is inside of. Whereas the inside view is of an interior or exterior, the outside view is of this inside, not directly of the interior or exterior. This may seem like quibbling, but as we have just seen, ignoring this difference is key to allowing Wilber to obscure the critical point that cognitive science and other approaches he puts in zone-5 really belong in outside zones, specifically zone-2 or zone-6. If he were to specify clearly that structuralism and other zone-2 approaches were in fact outside views of inside views, it would be obvious that cognitive science and other zone-5 approaches are outside views in the same sense.

Even with that understanding, however, there are still more problems with the way Wilber relates inside and outside approaches. As we saw earlier, he regards structuralism as a zone-2, outside approach, and he provides as an example of this approach studies in which individuals are asked how they would act in a particular moral situation. Their answers fell largely into three classes, that is, three major types of response to the hypothetical situation; on this basis, the three stage system consisting of preconventional, conventional and postconventional morality was developed. I agree with Wilber that this is an outside, or third-person approach. But no psychologist I'm aware of would consider the simple act of answering such questions introspection, or Wilber's zone-1 approach. If this is an example of introspection, then it's clear that all of us are engaged in introspection most of the time, because we constantly make choices like this in our daily lives.

This example is also inconsistent with Wilber's own definition of the inside of an interior. As we saw earlier, he defines it as that which “directly and immediately presents itself to your naked awareness”, contrasting it with the outside of an interior, which is composed of things “'I' see…in my mind”. The data employed by Kohlberg and other structuralists are by this definition clearly outside, not inside, interiors. They specifically ask their subjects to describe what they “see in my mind”. To the extent that introspection really views the inside of an interior, it generally refers to a much more detailed, moment-to-moment observation of thoughts and feelings as they pass through our mind. I find it questionable whether such observations have ever been used by structuralists to create stage models. Introspectionist data are used by cognitive scientists, but for the very different purpose of understanding how the mind works, not classifying stages of social development.

One Plus Three Make Four

To summarize the discussion so far, we have seen that Wilber's IMP is marred by several major inconsistencies. These inconsistencies all have at their root a confusion over the meaning of inside and outside. Thus we have seen that Wilber first defined (in Excerpt C) the inside and outside of exteriors as exteriors, and those of interiors as interiors, while later changing his view (in Excerpt D and Integral Spirituality) so that inside became essentially synonymous with interior and outside with exterior. In his latest treatment of IMP, in Integral Spirituality, he selectively oversimplifies his definitions of some zones, condensing “outside view of an inside view” to “outside view”. He uses the latter term to describe outside approaches, while the former term is misleadingly used to describe other approaches that are outside in exactly the same sense (cognitive science and biological phenomenology) as inside ones. Even introspection, which is an inside view as contrasted with what he calls outside views, is at least partly an outside approach by the definition of inside/outside given in Excerpt C.

Though these inconsistencies make Wilber's use of IMP look sloppy, I don't believe they are fatal to it. With a little more attention to his definitions, Wilber could probably fit all these approaches into his model. His integral mathematics, with its perspectives of perspectives of perspectives, seems to have a literally infinite capacity to represent approaches to knowledge. Just add more terms.

But the key point I want to make is that he can't include all these perspectives in a quadrant diagram without greatly expanding the number of quadrants. As I noted earlier, this is what both Goddard (2000) and Edwards (2002,2003) have proposed. Their solution to the problem may indeed be an improvement over the original four quadrants, but the result, to my eyes, becomes increasingly more cumbersome. Goddard proposed twelve quadrants. Edwards has proposed a separate quadrant diagram, indeed several such diagrams, for every holon. Theories are not supposed just to represent knowledge, information or concepts. They are also supposed to abstract and simplify them. If hundreds of quadrant diagrams are required to represent various aspects of existence, how much of an advantage do they have over simply using textual descriptions?

Moreover, as Edwards' discussions in particular make very clear, to use the quadrant diagram in this manner means that there is no longer even the possibility of any single diagram that can summarize, however simply and abstractly, all of existence. The four quadrant diagram that Wilber has used to depict forms of life from atoms to humans, which formed the centerpiece of his book Sex Ecology Spirituality and his Journal of Consciousness Studies article, and which appears unchanged in Integral Spirituality, has been rendered invalid. As I have discussed at length previously (Smith 2001c), to view the four quadrants as different aspects or now perspectives of a single holon is incompatible with using the quadrants to represent different levels of holons. You simply cannot do both.

This creates yet another problem with IMP. As shown by the examples he uses to illustrate the various zones (Table 1), Wilber clearly intends IMP to cover the study of social holons as well as individual ones. But the four quadrant diagram that IMP is ultimately based on (Figure 1) does not include social holons. It only represents social aspects of individual holons. So to cover all the approaches that involve the study of social holons, Wilber must jettison the four quadrant diagram completely, and work simply with integral mathematics. Beyond the fact that integral math has its own problems, as I have discussed previously (Smith 2003c), this means that his IMP loses its most important grounding. Indeed, it means that one of Wilber's most central concepts—hierarchy—no longer can be represented by the four quadrant model. In fact, Wilber no longer has an argument that existence is hierarchical. He may say that it is, but his four quadrant diagram does not demonstrate this.

Readers of my work at this site will know that I have long challenged the four-quadrant model, replacing it with a one-scale version. What I want to show here is that the one-scale model can not only represent all of Wilber's eight perspectives—and I believe any additional ones he may come up with—in an internally consistent fashion, but it can do so without sacrificing its ability to represent all of existence as a hierarchy. In other words, the IMP system can remain grounded in a basic, overarching view of life.

Let's begin by comparing the two models. Wilber's four quadrants represent two fundamental distinctions he makes in the properties of holons, between their individual and social aspects and their exterior and interior aspects. The one-scale model does not ignore either of these distinctions, but it represents them in a different way from that of the four-quadrant model.

With regard to individuals and societies, I recognize that they form a continuum of development and evolution—individuals develop and evolve into societies, and vice-versa—so it is not necessary to represent them in different quadrants. Like Wilber, I recognize a distinction between individual and social holons, but they are hierarchically related. That is, not only are individual holons found as lower holons within higher social holons, but social holons are found as lower holons within higher individual holons. In my view, for example, the metabolic networks within cells form a social holon, as do tissues, organs and other multicellular holons within organisms. Thus a social holon contains lower individual holons, and in turn is part of a higher individual holon—and vice versa. The two types of holon alternate thoughout the hierarchy.[16]

This contrasts with Wilber's view, which regards celestial bodies such as stars and planets as the social holons of atoms and molecules, and simple cellular groups such as bacterial colonies as social holons of cells. In this view, social holons are never part of higher individual holons. While individual holons are found within social holons, the four quadrant model does not see their relationship to the latter as hierarchical, but rather as different aspects of the same level of existence.

I have previously discussed at great length some of the problems with Wilber's view of the individual/social relationship (2001b, 2002b). I will not reiterate these, but just add three more:

- Wilber's definition of social holons is inconsistent with recent scientific studies. Complexity theorists have shown that many of the interactions occurring in human societies are characterized by a form of organization known as scale-free networks (Barbasi 2002; Smith 2003a). Scale-free organization is found, for example, in human social, business and academic relationships, and also characterizes to a large degree the organization of the internet (Barbasi 2002). Scale-free organization has also been described at lower levels of existence, in the molecular organization of cells (Jeong et al. 2000, 2001) and in the relationship of neural events in the brain (Equiluz et al. 2005; Archard et al. 2006). These are social holons in my hierarchy model. In contrast, scale-free organization is not found among the members or components of what Wilber considers to be lower level social holons, such as the atoms in stars, the molecules in planets, or the bacteria in prokaryotic colonies.

- Wilber's classification of social holons, as they are represented in the four-quadrant model, is also inconsistent with his own description of them in IMP. Note that in Table 1, above, he provides systems theory as an example of an outside approach to social exteriors. Systems theorists study, among other things, metabolic networks within cells and cell-cell interactions in organisms (see, for example, Kauffman 1993). No system theorist I'm aware of studies stars as a system of atoms, however, or planets as a system of molecules, for the simple reason that individual stars and planets are not systems of atoms or molecules except in an extremely weak and scientifically unchallenging sense.

- Wilber's four-quadrant model, as I noted earlier, cannot actually represent individual and social holons, but only individual and social aspects of holons. Moreover, apparently it can only represent aspects of individual holons, since he now maintains that social holons do not have four quadrants. So though he claims that individual and social holons are not hierarchically related, but in fact exist as different aspects on the same level of existence, he has in fact no way of representing their relationship at all. My model, in addition to representing individual and social holons, also recognizes, and can represent, individual and social aspects of each kind of holon (Smith 2001b,c)

So I see no need, nor even a possibility, of separate axes or quadrants for representing social and individual holons.

Interiors, in my model, also do not require a separate quadrant from that used to represent exteriors. To understand why not, we must recognize that most philosophers make a distinction between two aspects of what Wilber calls interiors. David Chalmers (who in fact is a member of Wilber's Integral Institute) refers to this distinction as the hard and soft problems of understanding mind or consciousness (Chalmers 1997). The soft problem concerns the contents or functional properties of mind, which almost all philosophers and scientists believe in principle if not yet in practice can be understood in empirical terms. For example, what I am thinking right now is a private, interior experience, but it must reflect activity in specific areas of the brain which may be identified. If we knew enough about the mind, most scientists and philosophers believe, we could describe the specific contents of any thoughts in terms of the activity or interactions of specific neuronal networks. So there is no reason why the contents of our thoughts should not be understood to be exteriors, in the sense that Wilber defines this term.

However, most scientists and philosophers accept that there is more to our thoughts and other phenomena Wilber describes as interior, than their content. There is also an ineffable experience associated with thinking, what philosophers often refer to as qualia, or “what it is like” to be someone or something. This is what Chalmers means by the hard problem of consciousness. There is considerable disagreement among philosophers over whether the hard problem is solvable, that is, whether consciousness in this sense can ever be understood in empirical terms. But even those who believe it may be can provide no clues to how this might be accomplished. There is no reason to believe, at the present time, that this aspect of mind or consciousness can be understood in terms of brain physiology, or anything else that might be considered exterior.

Does this aspect of mind therefore need to be represented with a second scale or quadrant? In my view no, because there is nothing hierarchical to be represented. Different holons or forms of existence may differ in the degree to which they have this experience, but not in a hierarchical sense. We cannot say, for example, that the ineffable aspect of the experience of a human individual transcends and includes the ineffable experience of a cell. What transcends and includes is always something that can be expressed in terms of content. For example, we obviously differ from individual cells in our ability to understand and use the kind of language that we do, but this difference, to the extent that it is hierarchical, is one of content. This content is always associated with experience, but in my model, this association is simply understood. That is, any exterior on the one-scale model is assumed to have some degree of experience associated with it. So it is not only unnecessary, but in my view misleading, to represent this experience in a second quadrant or axis.

To summarize the discussion so far, the one scale model recognizes the existence of social holons (as well as social aspects of holons) along with individual holons, and private interior phenomena as well as exterior ones. Moreover, these two features of existence are, in the one-scale model, closely related. Associated with each of the two major kinds of holons, individual and social, are two major kinds of perspectives, corresponding closely to Wilber's first-person and third-person views. Social holons, which are composed of the interactions of many individual holons, have a third-person view (S).[17] Individual holons, on the other hand, may have either a first-person view (I1)[18] or a third-person view (I3). This is because individual holons have a dual existence. They exist to some extent as independent holons, which have a first-person view; but they also exist as members of society, participating in many of its properties, and in this role they have a third-person view.

So Wilber's first- and third-person perspectives are understood in my model as the view from individual holons and social holons (or individual holons in a social context), respectively. As we have seen, he also refers to these perspectives as inside (first-person) and outside (third-person). In my model, this correspondence also holds, but only for individual holons. That is, the first-person perspective of an individual holon is an inside view, and the third-person perspective is an outside view. This is not the case for social holons, for reasons I will explain later (see also footnote 17).

What about the exterior/interior distinction? As I pointed out earlier, as Wilber uses the inside/outside terms, they correspond closely to exterior/interior. Inside in his model is an interior view of an aspect of a holon that itself can be either interior or exterior. Likewise, outside is an exterior view of an interior or exterior aspect.

I define exterior and interior somewhat differently, so that they are genuinely distinct from outside and inside, or third-person and first-person. An exterior is what any holon sees when it looks at holons at or below its own level or stage of existence. Thus when an individual looks at inanimate objects, or other forms of life, or even the physical bodies of other people, he is having an experience of an exterior. He is seeing the holon from above, and this, in my model, is an outside or exterior view. The interior, in contrast, is what an individual holon experiences when it looks at holons above itself. For us, this is primarily society. Since society, in my one-scale model, is hierarchically higher than its individual members, when an individual looks at society, he is looking at it from below, and the result is an interior view.

This may not seem intuitive. The interior is commonly expressed as mind or consciousness, consisting of thoughts, feelings, sensations, and so on, and these are usually thought of as the properties of an individual, not a society. But in my model, almost all mental phenomena—recalling that we are talking about mental contents, not qualia—are social properties. They result from the interactions of many individuals, and we experience these mental contents only by virtue of our membership and participation in society. This view is actually quite consistent with Wilber's postmodernism, which understands all individuals as embedded in an intersubjective matrix of thoughts that shapes all of our experience. We exist within this matrix by virtue of our thinking.

Individual/Social Pluralism

With these basic ideas in place, we can understand all of Wilber's eight perspectives in terms of interactions between individuals and societies. These are shown in Table 2. I will explain each of my terms in more detail below.

| Wilber's Zone | 4-Quadrant Location | Integral Math Formula | Holonic (I/S) terminology |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Inside of interior of individual | 1-p x 1-p x 1p | I1 –> S |

| 2 | Outside of interior of individual | 3-p x 1-p x 1p | S –> (I1–> S) |

| 3 | Inside of interior of society | 1-p x 1-p x 1p* | I3 –>S |

| 4 | Outside of interior of society | 3-p x 1-p x 1p* | S –> (I3 –> S) |

| 5 | Inside of exterior of individual | 1-p x 3-p x 1p | I1–> I |

| 6 | Outside of exterior of individual | 3-p x 3-p x 1p | S –> (I1–> I) |

| 7 | Inside of exterior of society | 1-p x 1-p x 1p* | I3 –> I |

| 8 | Outside of exterior of society | 1-p x 1-p x 1p* | S –> (I3 –> I) |

Table 2. A comparison of the eight zones of Wilber's Integral Methodological Pluralism as represented in terms of his integral mathematics (third column), and as interactions between individuals and society (fourth column). In the integral math terminology, 1p* refers to plural and is used by Wilber in the social quadrants. In his exterior zones (5-8), he would probably use “3p” (or “3p*”) for the final term in all cases, but I have used “1p” as I believe that is more consistent with his interior terminology. In the S/I interactions, arrows indicate direction of observation (subject to object), and subscripts denote first- or third-person perspectives.

Zone-1. As we saw before, Wilber describes zone-1 as the inside of the interior of an individual, and provides as an example introspection. In my model, this type of approach is represented by the independent individual looking at society (I1–>S). Because the individual is in the independent role, the perspective is first-person (I1); and because he is looking at a holon above himself, it is an interior view.

Zone-2. Wilber refers to this as the outside view of an individual interior. It is represented in my system by society (S) looking at the first-person individual looking at society (I1–>S). What does this mean? Simply that society is looking at the results of individual introspection. The independent individual, in examining his mind, looks at society from a first-person view. Society, with its third-person view, then looks at several or more of these first-person views. This corresponds to the “outside view of an inside view” which Wilber apparently intends to mean by zone-2, but which he simplifies as simply an outside view.

Zone-3. This is defined by Wilber as the inside view of a social interior, exemplified by the practice of hermeneutics, when individuals come to a shared understanding of the meaning of language. In my system, this involves individuals in the third-person mode (I3) looking at society. That is, individuals in their role as members of society look at this society.

This definition may seem inconsistent with my earlier statement that the third-person is an outside view rather than an inside view. But recall I said that this was the case only for individual holons. The third-person view of society is an inside view, because the inside of society, like the inside of the individuals making it up, is composed of thoughts and other interactions among these individuals.[19]

Zone-4. My definition of zone-4 follows in a straightforward way from zone-3. Since the latter is represented by third-person individuals looking at society, zone-4 is society looking at these results. Wilber calls this the outside view of a social interior, but as we have seen, it is really an outside view of an inside view.[20]

Zone-5. Turning now to Wilber's right-hand, exterior quadrants, we can understand zone-5 in a manner analogous to zone-1, except that it is concerned with exteriors instead of interiors. I am now representing zone-5 in a way that is consistent with zone-1, as an inside view of individual exterior, rather than as Wilber's “outside view of an inside view”, that we have seen really belongs in zone-2 or zone-6. The inside view of an individual exterior is represented by an individual holon in the independent mode (I1) looking at another holon (I). Since the latter holon must be lower than the observing holon, the dynamics could be more accurately represented as IH1 –> IL), where the subscripts represent higher and lower holons.

Zone-6. Likewise, zone-6 is represented by society (S) looking at this individual looking process. Just as structuralism (or cognitive science), in zone-2, synthesizes the reports of individuals looking at interiors, empiricism, in zone-6, synthesizes the reports of individuals looking at exteriors.

Zone-7. This is described by Wilber as the inside of a social exterior. What exactly does this mean? It should mean the way a social holon or society looks at exteriors. I don't find this notion very coherent, and Wilber's example of social autopoiesis strikes me as evidence that Wilber doesn't, either. Autopoiesis is the name Wilber gives to Maturana and Varela's approach to individual exteriors, but is it really applicable to social exteriors? I think he is inventing the term to fill a gap in his IMP.

If there is such a thing as an inside view of social exteriors, however, I think it is just as adequately represented, in my system, by an individual holon in the third-person mode looking at another individual holon. The third-person perspective is a social one, and since the object of the perspective is another individual holon, the view is of an exterior. While it may seem strange that a view of a social exterior could be represented entirely in terms of individuals, keep in mind that in Wilber's view, societies have no central or unitary consciousness, but basically consist of the sum of consciousness of all their individual members. If this is in fact the case, the only way any aspect of society can be observed from the inside is through individuals. I will shortly suggest, however, an alternative definition framed in terms of society rather than individuals.

Zone- 8. My definition of zone-7 makes more sense when we consider zone-8. This is Wilber's outside view of a social exterior, and exemplified by systems theory. As with zone-4 (see footnote 20), a more accurate representation of the dynamics of zone-8 would note that the society observing must be higher than the society observed. This is because an exterior can only be observed by a holon that is higher than the holon observed. Consistent with this, systems theory generally studies non-human societies, such as assemblies of molecules and cells. To the extent that systems theory is applied to human societies it is done by representing the latter as interactions of physical organisms, which are lower holons in this context.

In summary, the one-scale model can fairly adequately represent Wilber's eight zones or perspectives of knowledge. I don't present Table 2 as the final word on this matter, of course. Some of these definitions may need to be modified, and there are additional perspectives that could be represented. For example, as I suggested earlier, I think cognitive science should be considered a zone-2 and zone-6 approach, in Wilber's terms; that is, it is an outside view of inside view of individual interiors as well as exteriors. But if cognitive science belongs in these zones, what about structuralism, which Wilber provides as an example of a zone-2 approach, and empiricism, which he represents with zone-6?

If we compare cognitive science with empiricism, we see that while both work with the inside view of exteriors, empiricism takes this view at face value to construct its scientific view of the world, while cognitive science uses this view to gain insights into the brain. So while we might represent empiricism as S –> (I1 –> I), as indicated in Table 2, we could distinguish it from cognitive science by representing the latter as S –> [I –> I1 >I]. That is, cognitive science is the outside view of the individual (brain's) view of the inside of exteriors.

With regard to structuralism, as I discussed earlier, I don't think it is based on observations of introspectionists or phenomenologists. Structuralism builds on what I regard as I3 observations, so it might better be represented as S –> (I3 –> S). Then how is it distinguished from ethnomethodology, the zone-4 example? One way would be to reformulate hermeneutics (zone-3), as S –> S, society looking at itself. Theen ethnomethodology would be S –> (S –> S). The same representattions could also be used for zones-7 and zone-8, respecctively. However, the interior quadrant zones, 3 and 4, could be distinguished from the exterior zones 7 and 8, by representing the latter as SH –> (SH –> SL), where SH and SL denote higher and lower societies, respectively. Thus societies can view the exterior of lower societies, but the interior of societies on the same level as they are.

Obviously, these are only suggestions. This is a preliminary classification. What even this brief discussion should make clear, though, is that the one-scale model has the potential to describe all of Wilber's eight perspectives, and indeed many more, in terms of the interactions of individual and social holons. Wilber's integral math, as I suggested earlier, probably can also do so, but it suffers from a lack of precision. The first-person and third-person terms he uses in his formulas have different meanings, as Wilber himself admits (see footnote 8). That is, the first or third-person view means one thing when it is used to distinguish inside from outside, means a second thing when used to distinguish interior from exterior, and still something else when it refers to an individual or society. In contrast, since individual and social holons are precisely defined in my system (Smith 2001b), the perspectives themselves have precise definitions. I regard this as a significant advantage over Wilber's formulation. As we have seen, his changing or inconsistent meanings of outside and inside allow him to make some misleading representations of the approaches appropriate to each of his zones.

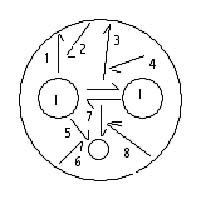

Another major advantage of my representation over Wilber's is that it can include these perspectives in a single diagram that represents the entire scale of existence. As discussed earlier, Wilber's four-quadrant diagram represents individual and social aspects of holons, and so is unable to represent more than a single kind of holon. Fig. 2 shows each of these perspectives as defined in my system, that is, as a specific kind of interaction between individuals and societies. For the sake of simplicity, I have included only a portion of the scale of existence in this diagram, mainly just humans and their societies, but the diagram can easily be expanded to include lower holons, simply by adding more concentric circles. The diagram could also be represented as the more familiar ladder of development, but the radial form allows the interaction arrows to be visualized more easily.

Fig. 2. A diagram showing Wilber's eight zones or perspectives of IMP in the one-scale model. The large circle is a social holon, the three smaller circles within the large circle represent lower holons. The two smaller circles of the same size (I) are individual holons that are members of the social holon, while the smallest circle is a different and lower holon (individual or social). The arrows indicate the perspectives of each zone, as numbered. The I1 perspective is indicated as an arrow (zones 1 and 5) going directly from a single individual holon to another holon, while the I3 perspective is represented as an arrow (zones 3 and 7) going from the interaction of two (or more) individual holons to another holon.

Being able to include these perspectives on a diagram of all existence is not simply a neat trick that allows us to represent a great deal of information in a relatively simple form. Fig. 2 strongly implies that the eight perspectives are not limited to humans and their societies, but could also exist among lower forms of life. All we have to do to visualize them is draw the same kinds of interactions among lower individual and social holons.

For example, consider the human brain, which in my understanding is a society composed of individual neurons. Fig. 2 suggests that individual neurons, like individual humans, can have private or “first-person” experience of both exteriors and interiors. The former type of experience (zone-5) would result from the individual neuron's interactions with lower holons, such as molecules in its immediate environment, or with non-neuronal cells (glia) that it contacts non-synaptically. The latter type of experience (zone-1) would result from the neuron's synaptic interactions with a great many other neurons. It would constitute the neuron's private view of the activity of a large ensemble or network of neurons of which it was a member.

The individual neuron, by virtue of being a member of a very large organization or network of neurons, would also have a third-person view, shaped by its interactions with these other cells. This third-person view would in effect by a property of the entire network, each individual member of which would experience to some extent. This third-person view of the neuronal “society”, derived from the interactions of all its member neurons, in fact is essentially the first-person view of the organism possessing this brain. That is to say, our first person view (I1) is a comprehensive summary of the third person views of all the individual neurons in our brain. It is the view of the entire society of neurons, which from their limited perspective is third-person.

This underscores the lesson that first-person and third-person are relative terms. Whether a view is considered one or the other depends on who is viewing the holon in question. As we move up the hierarchy, what is viewed by an individual member of a social holon as a third-person view is a first-person view for that social holon, and for the higher individual holon that includes that social holon. This higher holon in turn can have its own third person view, which becomes a first person view of a still higher holon that it is a member of. This is another, and I believe much more profound, sense of perspective in the hierarchy.[22]

Wilber of course could also apply his eight perspectives to lower forms of existence, by using a different four quadrant diagram and specifying that it is to describe some lower holon. However, to do this, he has to identify correctly another individual/social relationship—one that is genuinely analogous to that humans have to their societies—and as we have seen, his concept of social holons on lower levels of existence does not do that. This is one of the major flaws in the four quadrant model. Moreover, even if he applied his four quadrant diagrams to the same individual/social relationships that I do, such as cells and the brain, his need to draw a separate four quadrant diagram for each level of existence obscures the relationships that exist between different levels. For example, as I just pointed out, the third person perspective of a society at one level becomes a first person perspective at a higher level, when that society becomes incorporated into a higher individual holon. This kind of relationship can only be appreciated in a schema that can represent multiple levels, and their inter- as well as intra-level relationships, simultaneously.[21]

Conclusions

Wilber's Integral Methodological Pluralism, or IMP, represents a significant expansion of his four-quadrant model, in effect a doubling of the number of quadrants. It has the potential not simply to identify and classify the different ways that we obtain knowledge, but to reveal the limitations of each approach. It can show us clearly what researchers are actually doing (and not doing) when they study some phenomenon. At the very least, it has the potential, extending that of the original four-quadrant model, to help researchers in one area or discipline to understand and better appreciate the contributions of those in another area. At best, it may spur efforts, like Wilber's own, to synthesize these long-incompatible academic fields.

However, as Wilber has presented this new system, I think it suffers from being vague, confused, and/or inconsistent in the way many of its key terms are defined. In particular, his definitions of inside and outside are slippery, not always consistent, and result in some comparisons and characterizations that I find very misleading.

My alternative representation of his eight perspectives, as presented here, is based on a very simple idea. If everything—or at least everything with a perspective—is a holon, then all perspectives should be definable in terms of these holons and their interactions. My starting definitions follow in a straightforward manner from my answers to three basic questions:

- What are individual and social holons? As I have discussed at greater length before (Smith 2001c; 2002a), an individual holon has a mixed hierarchical structure and is able to reproduce itself and (in at least some forms) exist independently, that is, outside of higher social and individual holons. A social holon has a pure hierarchical or holarchical structure and cannot reproduce itself or exist independently of other holons.[22]

- What are exteriors and interiors? An exterior is what a holon sees when it looks at holons or other forms of existence below its level or stage in the hierarchy. An interior is what a holon see when it looks at holons at its own level or higher.

- What is meant by inside and outside? Inside is the view of a holon when it asserts its independence from other holons like itself. Outside is its view when it interacts with other holons like itself.

I have previously used this approach to show that many of the distinctions that Wilber draws in describing the properties of holons are redundant, that these properties can be understood solely in terms of the interactions of individual and social holons (Smith 2003b). The present discussion can be considered an extension of that work,and further evidence that the one-scale model is not only fully capable of representing all the phenomena that the four-quadrant model is, but can do so more economically. Fans of the four-quadrant model may not like this approach, but I hope they respect that in framing the debate in this manner, I have created a large and very visible target. That is, I don't attempt to hide, as I feel Wilber sometimes does, behind definitions that are sufficiently imprecise (or buried in some footnote) to allow easy deflection of criticism on the basis that the critic doesn't really understand what is being said.

Footnotes

1. Integral Spirituality, p. 4. This is not the final version of this book, to be published by Shambhala in August, 2006, but a condensed version titled What is Integral Spirituality? The link to this PDF is available through a search using this title in Yahoo. All of the passages from this book that I quote here are from the condensed version, but all of these passages also appear in identical form in the final version.

2. In the condensed manuscript that I am quoting from, only four zones are identified, with zones-1 and 2 corresponding to the inside and outside views, respectively, in both the individual and social interior quadrants, while zones-3 and 4 similarly cover both individual and social exterior quadrants. However, Wilber has since distinguished individual from social by designating the interior social zones as 3 and 4, and the exterior social zones as 7 and 8. Thus the exterior individual zones become 5 and 6. I use this terminology throughout this article.

3. Excerpt C.

4. ibid.

5. ibid.

6. Integral Spirituality, p. 5.

7. Excerpt D.

8. In an important footnote appearing only in the final version of Integral Spirituality, Wilber cautions us that there are some oversimplifications in his descriptions of IMP, and particularly of integral math (see below), which he engages in for the sake of easier understanding. His discussion here could be interpreted as an indication that inside and outside are not exactly the same as interior and exterior, respectively. However, if one looks at the actual examples he provides of inside and outside views, they do in fact always correspond to interiors and exteriors (the following quotes are from the condensed version, but the exact passages also appear in the final version). Thus he describes zone-2, which is an outside view of an interior, as “an objective, scientific, third-person stance” (p. 17). His discussion of this zone also includes such passages as: “But I can also try to see myself 'objectively', like others see me.” (p. 8), and “But even though you are working with interior realities (1-p x 1p), you are taking an exterior, 'scientific' or 'third-person' view of them.” (p. 19) So his description of an outside view of an interior clearly indicates that outside is exterior.

His description of zone-5, as I will discuss later in this article, is not as an inside view of an exterior, but rather as “an outside view of an inside view” (p. 75). But even here he clearly indicates that outside is an exterior view and inside is an interior view. Thus he describes this perspective as “what was available in the subjective-cognitive world of the frog, but they were still thinking about it in objective terms. It was the inside view of the frog approached objectively.” (p. 76). Equating inside with “subjective-cognitive” clearly defines it as interior, while the use of “objective” to describe outside indicates it is exterior.

Wilber also states, in the same footnote in the final version of Integral Spirituality, that his use of integral math perspectives (such as 1-p and 3-p, see below in this article) is confined to three terms, whereas four or five might be needed to capture fully the zone. He adds that this may make some of his definitions look different from those given in the Excerpts, even though they are not. But as we have seen, even the definitions in Excerpt C and D don't agree with each other. Moreover, as discussed in footnote 11 below, Wilber's more detailed discussion of these terms shows that his definitions have definitely changed from those presented in Excerpt C.

9. Integral Spirituality, p. 75.

10. ibid., pp. 6-7.

11. As far as I can tell, Wilber always refers to individuals in the upper right or exterior quadrant as 3p. This doesn't make sense to me. One of his terms should refer to exterior/interior, and one to individual/social. The exterior view is referred to by 3-p, so the individual should be 1p regardless of whether it is an individual exterior or interior. Of course, it is not 1p in the same sense that a subjective, first-person perspective is, but the point is that he needs one of his terms to refer to the individual/social distinction. He seems to be lumping individual and exterior into one term, but he doesn't do this when he refers to individuals in the interior quadrant. In other words, whether the quadrant is individual or social should be logically independent of whether it is exterior or interior.

As I noted previously in footnote 8, he says that his limiting the number of integral math terms to three may lead to some confusion, particularly if he uses the last three terms of a four term description, rather than the first three terms. If zone-5, expressed in four terms, were 3-p x 1-p x 3-p x 1p, then the last three terms, 1-p x 3-p x 1p, would describe an inside view of an exterior, and be consistent with his description of zone-1. However, as shown in the passage just quoted (cited in footnote 10), his three term description clearly applies to the first three terms.

12. As further proof of Wilber's inconsistency, consider this passage I quoted in the previous section:

This passage specifically describes Wilber's conception of zone-5, in an earlier work. (It was described as zone-3 in this passage, because at that time Wilber distinguished only four zones, the first two in both the upper and lower left-quadrants and the second two in the upper and lower right quadrants. See footnote 2). In this earlier passage, zone-5 is described in a fashion consistent with the other zones. In fact, the passage continues “…(1p x 3p), in both singular and plural forms”, clearly indicating that the first two terms of the zone-5 perspective should be 1-p x 3-p, not 3-p x 1-p (the terms are not hyphenated in the original quote because Wilber had not at that time made the distinction he subsequently makes between hyphenated and non-hyphenated terms).

It was only after Wilber developed his IMP further, that he changed his definition of zone-5. Why did he do this? As I suggest below, probably because the consistent view of zone-5 does not correspond to a major approach to human knowledge. Had he used this consistent view, some approaches would not have fit neatly into his eight perspectives.

13. Integral Spirituality, p. 76.

14. However, even to support this kind of relationship requires a view of introspection that is somewhat different from the way this procedure is usually understood. This point will be discussed later.

15. The reason that the inside view of exteriors receives much less attention than the inside view of interiors is that empiricism has long taken it for granted that this inside view that it in fact depends upon is accurate, that is, that our view of exteriors faithfully corresponds to what exteriors really are. If this assumption is true, there is no need for a special academic discipline devoted to understanding our inside view of exteriors. Understanding exteriors themselves, which is the goal of empiricism, is one and the same as understanding our view of them.

Now as it happens, this traditional assumption of empiricists, which the philosopher Wilfrid Sellars first referred to as the myth of the given, has been challenged by postmodern thinkers (and long before them, though in a different way, by the philosopher Kant). That is, postmoderns deny that individuals can know reality through their senses. So in the postmodern view there is in fact an important distinction to be made between our view of exteriors and the exteriors themselves. Wilber clearly accepts the postmodern critique of the myth of the given. In Integral Spirituality (final version) he devotes a great deal of space to arguing that all major spiritual traditions accept, to their detriment, this myth. Yet as Goddard (2000) pointed out, Wilber never actually makes the distinction, in his four-quadrant model, between a holon's view of exteriors and the exteriors themselves. In this model, there are interiors, which are consciousness or mental events, and there are exteriors, but there is no separate quadrant that corresponds to our view of exteriors. Or, as Goddard more cautiously concluded, either exteriors or our view of them are represented, but not both. In this respect, Wilber's model, I think Goddard might say, actually helps perpetuate the myth of the given, even though Wilber strongly endorses the postmodern view that there is no “given”.

16. More precisely, there are several hierarchical stages of social holons within any individual holon.

17. The reader might ask why social holons have only the third-person perspective. Actually, like individual holons, social holons have both perspectives, first and third, but only the latter is relevant to this discussion. Moreover, the nature of the perspective depends on who or what is looking at the social holon. From the perspective of the individual holon (I3), the perspective of the social holon is third-person, but from the social holon's own perspective, it is first-person (S1). That is, the third-person perspective that an individual holon experiences as a member of a social holon is—when fully realized by the social holon as the third-person perspective of all its members—a first-person perspective. Like an individual holon, the social holon can use this perspective to look at interiors, which would result from its interactions with other social holons, or at its exterior, which consists of other social holons or individual holons..

The social holon also has a perspective that is third-person from its own position (S3). Just as with individual holons, this perspective results from its interaction with other holons like itself, that is, other social holons. This perspective plays a very significant role on lower levels of existence, such as metabolic networks within cells and tissue and organs within organisms. However, it is not very well developed at our level. That is, human societies do not yet recognize themselves to a very large degree as members of a still larger form of organization. I would predict that with continued evolution, this perspective would play an increasingly larger role.

This demonstrates an important aspect of hierarchical relationships that I will discuss further below. The first- and third-person perspectives are relative. Whether a perspective is considered one or the other depends on the holon observing. Generally, when I use them I assume that the holon observing is the individual holon.

18. This is somewhat of an oversimplification. There is probably no such thing as a purely first-person view. Since all of our thoughts, in the postmodern view, are shaped by society, we are engaging in a third-person view whenever we think. In particular, our thoughts involve the use of language, something we only know through our interactions with others in society.

Wilber's reply is that he is defining first-person (which he also refers to as monological) purely in an operational sense, as what goes on in an individual's mind, even if that event is shaped by social interactions.

I'm not going to argue with this claim, though some have (Meyerhoff, 2004). But the issue here is, what exactly is it that we know by acquaintance? Is it the verbal or written reports of a phenomenologist, that he provides to theory-building structuralists or cognitive scientists? No, this is dialogical or intersubjective information. All that we know by acquaintance, so I claim, is contentless experience. This does not really fit into any of his eight perspectives, or we could say, it is within all of them. Anything in any of Wilber's eight zones that is considered knowledge—especally anything that becomes the subject of an outside view—must have content.

Moreover, even if this were not the case, much of what Wilber calls dialogical (intersubjective or third-person) would become monological. For example, any new theory, such as some form of structuralism, may initially exist only within one individual mind, that of its creator. So until that theory is published and transmitted to other minds, it would be just as monological as the thoughts that an introspectionist observes.

The presence in Wilber's zone 1 of social or dialogical aspects in fact reflects a key relation that exists between this zone and zone 2: today's dialogue become tomorrow's monologue. What I mean by this is that much of the socially organized knowledge that Wilber refers to as structuralism, empiricism, and so on, becomes incorporated, over time, into individual minds, where it then shows up as phenomenology. Many of the culturally molded thoughts of people today are a direct consequence of dialogical approaches pursued in the past. Much of what we moderns think was not thought by our ancestors, because they did not have access to much of this cultural knowledge that we have.

So I claim that there is virtually no human form of observation or knowing the world that is purely first-person monological. The very fact that we are embedded in an intersubjective matrix makes it essentially impossible to make any observation that does not have a dialogical aspect. Indeed, this is what being in this matrix means: that we are essentially dialogical creatures. If it were really possible for an individual to pursue a purely monological approach, then that individual would not be embedded in an intersubjective matrix.

For the same reason, introspection is not limited to interiors, either. By virtue of his reliance on language, the introspectionist must observe exteriors, because language—contra Wilber—is partly an exterior phenomenon. I don't simply mean that to use language we must engage in physical, behavioral activities like gesturing, speaking or writing. Language is associated with certain areas of the brain, and undoubtedly individual words and other linguistic constructions are associated with specific networks of neurons. So while Wilber defines introspection as a form of observation directed at the inside of individual interiors, it is neither wholly inside, wholly individual, nor wholly interior.

19. See footnote 17. What we as individuals call the third-person view is the first person view of the society we belong to. This is because society, to the extent that it itself is an independent holon, is composed of many third-person interactions that sum, as it were, to a first-person view. This first-person view, like that of an individual, can see the inside of interiors as well as exteriors.

This relationship holds throughout the hierarchy. For example, what we call a first-person view for an individual is a third-person view for the cells in the brain of that individual. I discuss this later in this article.

20. Wilber provides as an example of a zone-4 approach ethnomethodology. Just as structuralism (or more accurately in my view, cognitive science), in the upper interior quadrant, takes the results or data of introspection of several or more individuals and incorporates them into a larger framework, ethnomethodology takes the results of hermeneutics applied to several or more societies, and incorporates them into a larger, comparative framework. Ethnomethodology, we could say, builds structures of social meaning. Note, however, that a society can only practice hermeneutics and ethnomethodology on societies at its level or lower. That is, it cannot understand the meaning of language in a higher society, and likewise it cannot incorporate a hermeneutic analysis of a higher society into an ethnomethodological approach. Thus zone-4 might more accurately be represented in my system by SH –> (I3 –> SL), where SH and SL refer to higher and lower societies, respectively.

21. As an aside, this provides an answer to Wilber's assertion that societies consist of the interactions of their individual members, rather than the individual members themselves. In Integral Spirituality (p. 77), he says:

I should say that I think this is Wilber's position. I'm not completely sure, because in a stunning display of inconsistency, even by his standards, Wilber adds a few lines later, “The way we put it is like this. A social (sociocultural) holon is composed of individual holons plus their interactions…The individual holons are inside the social holon, their exchanged communication is internal to the social holon.”

I don't know whether the latter statement is his actual position on the matter or whether this is just one more example of his sloppiness as a writer (does anyone at Shambhala bother even to read, let alone edit, Wilber's manuscripts before publishing them?). But Luhmann's view—and Wilber's, if he really agrees with it—results from a failure to appreciate that holons at different hierarchical levels or stages have different views of the same phenomenon. To say that society is composed of the interactions of its individual members is a third person view of the individual (I3). But the society itself, for which this same view is a first-person perspective, in fact sees itself somewhat differently.

Consider the brain. If a neuron has some small amount of awareness—as Wilber asserts, and as I believe may be the case—it could experience itself as part of a vast network of interactions. That is, the neuron has direct connections with dozens, hundreds or possibly even thousands of other neurons, and indirectly, through them, connections with literally millions of other cells. So to the extent a neuron has awareness of being a member of a larger holon, it would understand the latter as composed of the interactions of many neurons. It could not directly experience the larger holon as a brain, as a massive association of neurons like itself.

But a human being, being higher than a brain, can see the latter as composed not only of the interactions of neurons, but also—indeed, lacking the sophisticated observations of science, primarily—as a group of neurons. When we see a brain—as we might in an animal or a person being operated upon, for example—we do not see it as a network of interactions. We see it as a material object. We of course see our own body parts in this way as well, even though all of them are also composed of interactions of cells.

This point is even clearer at still lower levels of existence. Consider a molecule. Is it composed of atoms, or of the interactions of atoms? Both. From our much higher perspective, we conventionally say that a molecule is composed of atoms, but we could just as well that it's composed of the interactions of atoms. Indeed, all of the functional properties of molecules emerge from the interactions of its component atoms. For example, the signal property of an amino acid molecule is its ability to carry two electrical charges (acting as a zwitterion), which allows it to buffer the pH of the intracellular environment. The amino acid can ionize at either of its ends, and this ionization depends on the interaction of hydrogen atoms with oxygen and nitrogen atoms. Likewise, the signal property of a protein molecule is its ability to adopt a highly specific conformation, allowing it to function as an enzymatic catalyst. This conformation depends on the interactions of certain atoms within certain amino acids of the protein.

So we can describe a molecule as both a group of atoms, and as the interactions of these atoms. Either understanding is valid. Likewise, we can describe a multicellular holon such as the brain as both a group of cells, and as the interactions of these cells. Both views are correct, they simply reflect the view from different positions in the hierarchy..

We can say exactly the same thing about human societies or social holons, and now we see the fallacy, or more precisely, the limitations, of Luhmann's view. Are societies composed of individual humans or of their interactions? Both. We—people like Luhmann, for example—tend to see them as interactions, because—like cells within the brain—we are embedded within the society, and experience it primarily through our interactions with it. This is our I3 perspective. But there is a potential perspective—I would say the one adopted by a still higher form of life—that would see human societies as a mass of individuals. Thus societies can be considered to be composed of their individual members or of the interactions of these members.

Though it's not directly relevant to our discussion of different perspectives, I want to add that for Wilber to accept Luhmann's view is yet another manifestation of his inconsistency. As discussed earlier in this article, Wilber gives as examples of lower social holons stars, planets and bacterial colonies. Is a star composed of the “communications” or interactions among its member atoms, as opposed to the atoms themselves? I don't know a scientist who would see it that way. Likewise, no one would describe a planet as simply the interactions of molecules, or bacterial colonies as simply the interactions of bacteria. So Wilber's description of social holons as consisting of the interactions of their individual member holons, rather than of the individual holons themselves, does not apply to many forms of existence that he himself defines as social holons.

22. As discussed elsewhere (Smith 2001b,c), social holons are independent when they first evolve, only losing their independence as evolution proceeds to create a higher individual holon that incorporates them. So human societies, in particular, have a degree of independence that is not seen in social holons of lower levels.

References

Archard, S., Salvador, R., Witcher, B., Suckling, J., Bullmore, E. (2006) A resilient, low-frequency, small world human brain functional network with highly connected associatied cortical hubs. Journal of Neuroscience. 4, 63-72

Barabasi, A.L. (2002) Linked (NY: Perseus)

Chalmers, D. (1997) The Conscious Mind (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Equiluz, V.M., Chialvo, D.R., Cecchi, D.A., Baliki, M., Apkarian, A.V. (2005) Scale-free brain functional networks, Physical Review. 94, 018102

Goddard, G. (2000), Holonic logic and the dialectics of concsiousness : Unpacking Ken Wilber's Four Quadrant Model, www.integralworld.net.

Jeong, H., Tombor, B., Albert, R., Otltvai, Z.N., Barabasi, A.L. (2000) The Large-scale organization of metabolic networks, Nature 407, 51-54

Jeong, H., Mason, S.P., Barabasi, A.L., Otltvai, Z.N. (2001) Lethality and centrality in protein networks. Nature 411, 41-42.

Kauffman, S. (1993) The Origins of Order (NY: Oxford University Press)

Smith, A.P. (2001a) Quadrants Translated, Quadrants Transcended

Smith, A.P. (2001b) All Four One and One For All

Smith, A.P. (2001c) Who's Conscious?

Smith, A.P. (2002a) The Dimensions of Existence

Smith, A.P. (2002b) God is Not in the Quad

Smith, A.P. (2003a) Small World, Big Cosmos

Smith, A.P. (2003b) Wilber's Eight-Fold Way

Smith, A.P. (2003c) The Pros and Cons of Pronouns

Wilber, K. (2002a) Excerpt C: The Ways We Are in This Together. wilber.shambhala.com

Wilber, K. (2002b) Excerpt D: The Look of a Feeling: The Importance of Post/Structuralism. wilber.shambhala.com

Wilber, K. (2006) Integral Spirituality