|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Andrew P. Smith, who has a background in molecular biology, neuroscience and pharmacology, is author of e-books Worlds within Worlds and the novel Noosphere II, which are both available online. He has recently self-published "The Dimensions of Experience: A Natural History of Consciousness" (Xlibris, 2008). Andrew P. Smith, who has a background in molecular biology, neuroscience and pharmacology, is author of e-books Worlds within Worlds and the novel Noosphere II, which are both available online. He has recently self-published "The Dimensions of Experience: A Natural History of Consciousness" (Xlibris, 2008). SEE MORE ESSAYS WRITTEN BY ANDY SMITH Why It MattersFurther Monologue with Ken WilberAndrew P. SmithKen Wilber's four quadrant model is in many ways a culmination and summary of his theoretical work over the past twenty-five or thirty years, a map of existence he offers as a grand synthesis of human knowledge of all kinds, scientific, scholarly and spiritual. But as I have argued in great detail in a book and in a series of articles (Smith 2000a-c, 2001 a-i), the model has serious flaws. Among other problems, it defines levels of existence inconsistently; it ignores important classes of lifeforms or holons; it fails to take into account certain well-documented forms of evidence; its view of societies and social relationships is logically inconsistent; and its view of consciousness or interiority is either inconsistent or incoherent. While acknowledging certain problems with my own model (Smith 2001c), I strongly believe it's both far more consistently conceived as well as more faithful to well-established evidence. Wilber has not yet responded to any of my criticisms, which doesn't greatly surprise me. Part of the reason, I'm sure, is that he has his hands full with other critics, particularly much better known and more widely read ones. He simply doesn't have the time to answer everyone who has differences with him. But I also realize that Wilber has far too much invested in his four-quadrant model to entertain major changes to it now. This investment is not just the time and effort that went into developing the model, which continues to grow and be modified over time. The Integral Institute which Ken and some others recently founded has been set up explicitly to promote the four-quadrant model. To admit at this point that the model has substantial flaws might seriously undermine the Institute's rationale. One might well ask why his model needs any further promotion. In a recent interview (Wilber 2001), Ken said that a major purpose of the Integral Institute is to make academia more aware of his ideas, so that graduate students and other young scholars don't have to justify why they want to apply these ideas to their particular areas of interest. Since Frank Visser tells us that Wilber is the most widely translated academic author in the world, it's hard for me to believe that any resistance his followers encounter in universities is due to academics' lack of familiarity with his work. I doubt very much that there is a major philosopher, pyschologist or social scientist on the planet who has never heard of Ken Wilber, though probably a large majority of scientists are not familiar with his work. Certainly his books are just as much available as those of any other author read by students and professors across the country. So the Integral Institute's focus on promoting the views of a single thinker, no matter how seminal he is, strikes me more as that of a business trying to establish its product as the dominant one in the marketplace than of academics engaged in free discussion of ideas. Though I very much appreciate Ken's efforts to raise awareness of holarchy as perhaps the central organizing principle of existence, and to bring spiritual concepts into all areas of life, I'm a little astounded at the Integral Institute's presumption that certain basic issues have been settled, and are no longer subject to debate.[1] It's one thing to use the considerable power of a nonprofit organization to promote recognition of higher consciousness, quite another to apply that power to a particular individual's theories related to higher consciousness. One can accept the existence of higher consciousness, and maintain a spiritual practice designed toward its realization, without accepting everything that Wilber says. This is the key distinction that the Integral Institute seems to be blurring, implying that if you believe in the importance of spirituality then you should buy the entire Wilber package. All of my material critical of Wilber's model is available online, and I see no point in going over these arguments again. Very few people have tried to criticize them, and I believe I have adequately rebutted those who have. What I will do instead is address the significance of this debate. Many of those who are following this argument may wonder if it's really that big a deal. Ken Wilber has his model of the holarchy, I have mine. Neither model is very much concerned with the details of existence, the kind that concern scientists, psychologists and other scholars. The models are mostly just ways of arranging everything, and may seem to be largely a matter of personal preference. Does it really matter whose model we follow? I believe it matters for the same reason that the Integral Institute believes it matters: because models help define the questions we believe are important, the areas of research that we pursue. Every model makes certain predictions, which it's the function of further research to test. Just as significant if not more so, and generally much less appreciated, every model also rules out some areas of inquiry--either directly by claiming they are unimportant, irrelevant or even nonexistent, or indirectly by ignoring or not recognizing them. So what I want to do here is compare the implications of my model with those of Wilber's in several critical areas. Though this discussion will require some resurrection of earlier arguments and criticisms, I will try to keep these as brief as possible. I will also draw on material from a book I'm currently writing, The Dimensions of Experience, which is referred to here as simply in preparation.

The Evolution of SocietiesLet's begin by contrasting Wilber's view and mine on the social dimension. In Wilber's model, social holons, such as human societies, are ranked neither higher nor lower than their individual members, but are considered just a different aspect of life at a particular level. In my one-scale model, societies are always higher than their individual members. While any society and its members are represented on the same level of existence, societies form higher stages within this level. Wilber's view, as I have discussed in detail elsewhere (Smith 2001e), suffers from a major inconsistency, which becomes apparent as soon as we ask just what social means. On the one hand, he says that every holon has a four-fold nature, which includes a social dimension. So it appears that the social is just another feature of any holon which, from a different point of view, appears as an individual. On the other hand, Wilber makes a distinction between individual and social holons, representing one type in one quadrant of his model and the other type in another quadrant. In doing so, he implies that not all holons, after all, have a social nature; some holons are individual, some are social. The result is a conflation of two different definitions of social: on the one hand, it's defined as a universal aspect of every holon, but on the other, as a particular kind of holon. Both of these views can't be correct. There simply is no holon which, viewed from one perspective, is an individual, and viewed from another, is a society. I may have both an individual nature and a social nature, but my social nature is not the same thing as the society of which I'm a member. Wilber's description of the social is not only logically inconsistent, as has been noted by others as well as by myself (Goddard 2000), it also fails to address the actual evidence. If every holon has a social as well as individual aspect, we would expect that every form of existence would exhibit a strongly social nature. But this is clearly not the case. There are many kinds of organisms, and many kinds of cells, that do not form societies, and which exhibit a very minimal set of interactions with any other form of life. At the very least, this means that the four quadrants, fundamental and universal though they're supposed to be, are not equally developed for all forms of life. Every form of life has an individual exterior and interior, but not every form, it seems, has a social aspect. This point is obscured in Wilber's four-quadrant graphic, which shows an example of a society or social holon at every level of existence, but which fails to emphasize that there are many holons on every level that do not form societies.[2] This contrasts very starkly with the fact that holons on every level do have both exterior and interior aspects.[3] My model, in contrast, not only can handle this fact of life, but accounts for it explicitly. It's built into the very construction of the model. Every level consists of several stages, and on any level, the lowest stage is represented by asocial holons, those that exist more or less autonomously of higher forms of life. As holons emerge that interact socially, they form social holons, higher stages on this level, with each stage consisting of interacting holons of the stage below it. This model thus not only predicts that every level has holons with no social organization, but shows how they are related to other holons. As I have discussed elsewhere (Smith 2001e), this model can also clear up Wilber's logical inconsistency in the definition of social. In my model, every holon--social as well as individual--has both an individual and a social dimension or aspect. These aspects are defined explicitly in terms of higher vs. lower relationships on the single scale. Though there are other ways to resolve this inconsistency, they all apparently involve making the four-quadrant model still more complex, adding new quadrants or dimensions (Goddard 2000). Most important, though, the one-scale model provides a simple rule for understanding how social holons are created from individual holons, and how social holons evolve into still higher social holons. This rule is stated as follows: on any level of existence, higher, social stages are formed by the interactions of individual holons. The greater the number and complexity of these interactions, the higher the resulting social holon. So whenever individual holons interact, by definition a higher stage is formed, or is in the process of being formed. With this general background, let's now address a particular issue, and see how the two models handle it. Consider the relationship of different societies to each other. How are modern Western societies, for example, different from those of developing countries? This is obviously a very timely issue, of critical interest to everyone on our planet, where not a day goes by without strife and tension between these societies. On some days, such as Sept. 11, 2001, the tension may rise to truly astronomical levels. According to Wilber's model, and mine (Smith 2001d), societies can be ranked according to their position in the holarchy. Some are considered higher, more evolved, than others. I realize this is a very sensitive issue for many people (DiZerega 1999; Edwards 2001), and that this position can be used to justify Western dominance of non-Western societies. However, at the very least, I think most people will agree that societies can develop and pass through stages, and that these stages tend to occur in a certain sequence.[4] The theory of Spiral Dynamics, popularized by Don Beck and enthusiastically supported by Wilber, identifies about 8-10 such stages (Beck 2000). If we accept this idea, or indeed any view of social evolution, a critical question, obviously, is how a society passes from one stage to the next. Ken Wilber's model, as far as I can see, has no substantive answer to this question. Wilber and Beck can provide an endless catalog of descriptive details of each stage, but nothing in the way of meaningful dynamics (rather ironically, given the name of this theory) that might help us, for example, predict when, where and which societies might begin to change. Wilber and Beck do say that any stage of society reaches certain limits, which can only be transcended by evolving into a higher stage. But history is full of examples of societies that, upon reaching certain limits, did not evolve further, but simply achieved stasis, regressed to a lower stage, or became extinct. Reaching some kind of limits, therefore, may be a necessary cause of further social evolution--I for the most part agree with Wilber and Beck that it is--but it clearly is not a sufficient cause. In my model, in contrast, the answer to this question, or at any rate an answer, is implicit. In this model, as I just observed, societies are ranked according to the number and complexity of the interactions of its members. Therefore, as societies evolve, these interactions increase and become more complex. This understanding immediately allows us to predict some of the forces that are likely to play a major role in social evolution. One such force would be increasing population, because that not only increases the number of interactions between people in a society, but makes it likely that the complexity of interactions will also increase--as when, for example, groups begin to coalesce within this society, as interacting units composed of many people. The larger the population of a society, the more difficult it is for everyone to interact with everyone else without such intervening groups. A growth in population by itself, of course, will not ensure that a society evolves to a new stage, nor can we point to a simple relationship between population size and complexity. But population growth is definitely a force making evolution more likely. When such growth suddenly explodes, my model says, the probability of emergence of a new stage increases. A second force that increases the complexity of interactions among people is developments in communications technology (or indeed, in any form of technology, regardless of what it's called, that increases social interactions). The emergence of the printing press, telephone, radio, television, personal computer, internet, and so on (as well as cars and airplanes), have all been associated with rapid social evolution in the West, precisely because they increase not only the number of interactions any one individual can have with other individuals, but also the kinds of interactions. Without going into details (see Smith 2001d, i), we can distinguish between direct, face-to-face interactions, and many different kinds of indirect interactions (e.g., the kinds of interactions that occur between people through their participation in mass media). In contrast, many non-Western societies which until recently lacked or trailed in the development of such technologies have evolved much more slowly. Still another major force in social evolution is certain developments in political organization, such as those that promote democracy. Democracy not only allows people greater freedom to interact with other people, but demands such interactions. If no one person or small group of people is to have most of the authority and decision-making power in the society, then institutions must emerge that decide how this authority will be distributed. The formation of institutions within a larger society, again, increases the number and the kinds of interactions among individuals. People in institutions must interact with other people at multiple levels, again, greatly increasing the complexity of the process. These forces, and others that also promote greater social interactions, don't operate completely independently of one another, of course. They often enhance one another, as for example when new forms of technology promote political changes, or population growth induces development of new technology. The essential point, though, is that the concept of increasing social interaction provides a focal point for research in this area in a way that Wilber's model does not. It allows us to move beyond pure description--which it seems to me is mostly what Wilber's (and Beck's) model is about--and identify forces or causes of change. In fact, as I have discussed in detail elsewhere (Smith 2000a,c), and will touch upon later in this article, this understanding provides us with the basis for a view of evolution that incorporates all three of the major theories or classes of theories of evolution recognized by most scientists today--Darwinism, cultural evolution, and complexity theories. In saying this, I don't mean to denigrate the work of either Wilber or Beck. Beck, in particular, is a man of action who does not simply theorize but has played a very active role in social change around the globe. Wilber's Integral Institute, notwithstanding the criticisms I have of its theoretical basis, is similarly trying to go beyond words and engage society. I have great respect for people who don't simply talk about change, but who immerse themselves in the process. But whatever lessons they have learned from practice, both continue to emphasize description over process.

The Relationship of the Social to the InteriorLet's now bring the concept of interiority into the discussion, and its relationship to the social. In Wilber's model, interior properties of holons, like social properties, are represented by a distinct quadrant. As with the individual-social relationship, the exterior-interior relationship is not a matter of higher vs. lower, but of different properties or aspects of a holon existing on the same level. In the one-scale model, in contrast, the interiority of any particular holon is generally represented as being higher than its exteriority.[5] In fact, for individual holons that are members of social holons, their degree of interiority is directly related to the ranking of this social holon. This is because, in my model, interiority (to an extent that I will qualify later) is understood as what a holon experiences as it participates in the social holons of which it's a member. Thus the interior experience of people today results from their participation in the modern societies they live in. The interior experience of people of earlier societies resulted from their participation in the somewhat simpler social arrangements they were embedded in.[6] This understanding makes it possible to bring interior experience onto the same scale of holonic properties as exteriors. It also enable us, again, to account for an important observation that Wilber recognizes but which his model can't explain or provide any insight into the causes of that the interior experience of holons develops in parallel with that of social holons of which they are members. In Wilber's model as well as mine, the higher the social holon of which people are members, the higher their interior experience (or again, for people who object to ranking societies, we can just say that every type of society is associated with a different type of interior experience). Thus modern people, according to Wilber, have cognitive functions not exhibited by people of two thousand years ago. The latter, in turn, were more cognitively developed than people of ten, twenty or fifty thousand years previous. Why? How do human beings acquire these new mental and emotional properties or abilities, and why is it that they always closely parallel social development? To answer this question, we first need to recognize that the differences between ourselves and people of simpler societies are probably not as great as Wilber has commonly implied that they are. DiZerega (1999) has pointed out that studies of people of less-developed societies show that they are just as capable of rational thought as members of large Western societies. Similarly, Pinker (1997) argues that the tasks people of prehistorical eras had to perform in order to survive--hunting game, growing crops, making tools, and so forth--required just as much ability to reason and engage in abstract thought as moderns exhibit in their everyday lives. Edwards (2001) insists that people of indigenous societies often exhibit a kind of intelligence as well as ethics lacking in Westerners. To these arguments based on behavioral observations or conjectures can be added the point that while Wilber's four-quadrant model associates a different type of brain with every type of society, the differences he proposes are purely hypothetical. They have yet to be detected scientifically. In fact, it is the universal view of scientists that human beings who lived as long ago as 50,000-100,000 years were the same biological species as those of today, possessing anatomically identical brains. In light of this evidence, as I have argued elsewhere (Smith 2001a,c,g), Wilber's separation of different societies and their members into distinct levels of existence, implying that their differences are as great as those between say, an organism and its cells, or a cell and its molecules, is highly problematical. The relationships between these "levels" and the lower ones in his holarchy are very different, one of numerous examples of inconsistencies in his model. In my one-scale model, in contrast, different human societies represent different stages all within a single level of existence. Like cells in a tissue, or atoms in a molecule, members of different societies are physically and biologically virtually identical. Thus relationships on different levels are consistent. Nevertheless, I agree with Wilber that there are significant differences in interiority between modern people and those of earlier societies.[7] But if their brains were virtually identical to ours, what accounts for these differences?[8] Again, it's the number and complexity of interactions between people. The more complex a society in which people live, the greater the complexity of interactions they have with other members of this society. It's these interactions, as I noted above, that determine an individual's interior experience, because this experience results from looking at, or perceiving, these interactions. The same brain, embedded in a more complex social environment, will experience more complex forms of interiority. Therefore, interiority and sociality will always evolve together. They are indeed different aspects of the same phenomenon or process--a point that Wilber tries to make with his concept of a four-fold nature for holons, but which my model actually elucidates. It explicitly tells us what this connection between the two is. I return to this point later in this article, using specific examples to illustrate how interiority is related to sociality. One important implication of this view for future research should be obvious. If we want to understand how the interior experience of people of a particular society evolves, we should analyze the kinds of interactions they engage in with other people. There is very little that studies of brain structure, no matter how detailed a molecular investigation is performed, can tell us. Though my one-scale model is sometimes criticized as being overly reductionist, and giving short shrift to interiority, in fact here it places much less emphasis on individual, exterior structures than Wilber's does. Because Wilber views his four quadrants as equal, he often seems to presume that studies of each quadrant are equally important in addressing any phenomenon ("All Quadrants, All Levels"). In my model, where distinctions between exterior and interior, and individual and social, are made within a single scale, one does not necessarily take this approach. My model also also has very different implications for how we go about defining differences in interiority between people of different societies. As I noted earlier, there is some evidence that people of earlier or simpler societies were or are just as capable of rationality as we are. This presents a major problem for Wilber, who claims that modern societies are so different from earlier ones as to transcend them as genuinely new levels. In my model, in contrast, where different societies form different stages on the same level, the differences in interiorities are not so much actual as potential. They result largely from their social environment, and can quickly change when that environment changes. This has important implications for how we, as anthropologists or as historians, study people of other societies. The key here is to determine not what people can experience--for example, whether they are able to perform as well on simple tests of logic or arithmetic or ethics as people of another society--as what they do experience. One way to approach this might be to determine the reactions people have to a certain kind of event in their lives, an event that we can agree ahead of time is of major and universal significance to all people. Consider the death of a loved one, for example, and the effect it has on the deceased's survivors. There are many kinds of reactions they could have, including 1) thoughts that the deceased is now in heaven or some other pleasant place; 2) memories of the deceased's life, experiences one shared with that person; 3) thoughts of what the deceased contributed to society; and 4) concerns of the future, and how one is going to live--emotionally or economically--without that person in one's life. Though people of any society may be capable of responding in all these ways and others to a death of someone close, if interiorities really do differ with society, we would predict that some types of responses would be stronger, and more common, in some societies than others. This kind of analysis, much more than any test of abilities, would be the way to define and distinguish such differences. It would provide a glimpse into interiorities as actually manifested in members of that society, as opposed to what they can potentially manifest when situated within a different, more modern society.

IntersubjectivityTalk of social interactions and interiority should lead us directly to the concept of intersubjectivity, which has the potential to unify them. Intersubjectivity is a key idea in modern philosophy that Wilber has discussed at some length in several of his books (see Hargens 2001b for an excellent discussion of Wilber's views in this area). Ken's treatment of this subject, it seems to me, is a good illustration of both one of his great strengths as a theorist, and one of his weaknesses. The strength is that he takes a concept that has been previously been developed by other thinkers, and shows that its scope can be greatly extended. Thus while intersubjectivity conventionally refers to relationships between human beings, and particularly those that result from our use of language, Wilber argues that it also is manifested in non-linguistic forms, and that it can apply to other, non-human forms of life or holons. In fact, Wilber sees intersubjectivity as a universal principle in the holarchy, with the kind or kinds that we humans experience just a particular example of a more general phenomenon. To a very great extent, I accept Wilber's reasoning. I think it's a major accomplishment of his to integrate this postmodern insight, as he puts it, with holarchical thinking. However, the weakness that I feel Wilber exhibits here (and as we shall later, in other areas as well), is that in his desire to make his four-quadrant model as comprehensive and inclusive as possible, he applies the notion of intersubjectivity in a very sweeping manner. Thus he asserts:

Intersubjectivity [is] woven into the fabric of the Kosmos at all levels...[it] is true not only for humans, but for all sentient beings as such.[9] I think this is going a little bit too far. As far as I know, to support this claim, Wilber has mostly pointed out that other mammals also exist within an intersubjective framework:

Since humans and dogs share a similar limbic system, we also share a common emotional worldspace ("typhonic"). You can sense when your dog is sad, or fearful, or happy, or hungry...Of course, this is not verbal or linguistic communication; but it is an empathic resonance with your dog's interior, with its depths, with its degree of consciousness, which might not be as great as yours, but that doesn't mean it's zero. Dogs and wolves, however, are still fairly intelligent creatures. What about lower organisms, such as invertebrates? What about single cells? Can we really argue that they, too, share an intersubjective space? What would intersubjectivity mean for such creatures? At least two problems are raised here. First, it should be obvious that intersubjectivity presupposes social interactions. In order to "share" any kind of "worldspace", there have to be other forms of life to share it with. But as I noted earlier, there are many forms of life that have virtually no social relationships at all (see also Smith 2001h; Smith, in preparation). For example, green plants, as well as non-photosynthetic groups such as fungi, are basically individuals unto themselves. Though they may interact in certain ways with other members of their species, this interaction is not just far more rudimentary than the interactions of higher vertebrates; it is of a completely different kind, not involving (so I claim) any kind of subjectivity on the part of the interacting lifeforms. The most basic social interaction of any kind--the foundation upon which all other social relationships (within members of a single species) are ultimately built--is sexual reproduction. Not all plants reproduce sexually, however, and though most do or can, this interaction involves no active participation on the part of the lifeforms. The interactions take place at the gamete (that is, cellular) level, and the gametes are brought together by forces completely beyond the immediate control of the plant, such as insects and wind. This process, to be sure, is shaped by evolution, by natural selection, which involves a kind of interaction between members of one species as well as of other species, but I think it would be very difficult to argue that evolution provides an intersubjective framework from which individual subjectivities of specific individuals arise.10 The same point is illustrated almost as well by the most primitive invertebrates, such as Poriferans (sponges) and Coelenterates (coral, jellyfish, Hydra). Though some of these species live in colonies, the latter are extremely simple forms of social organization, resulting mostly from the rather unremarkable physical fact that reproduction tends to create a large number of individuals of one species that live in the same place (just as we find certain plants of the same species growing together in grasslands and forests, for example). Also as with plants, these simple invertebrates often reproduce asexually, and if they reproduce sexually, they do so by producing gametes that are released into the aquatic environment in which they live, finding each other without the need for copulation. Furthermore, such organisms have little of the structural or exterior equipment needed to interact with other members of their species. Sponges have no nervous system, while Coelenterates have a decentralized neural net and sensory receptors that respond primarily to variations in intensity of such modalities as light, touch and certain chemical substances. This mode of perception will be discussed further later. As I have argued elsewhere (Smith, in preparation; see also Smith 2000a; Smith 2001e), such lifeforms exhibit (to an almost complete degree in the case of plants, to a lesser but still very significant degree in the case of the simplest invertebrate organisms) what I call zero-dimensional experience. It's zero-dimensional because it makes no distinction between self and other. The organism experiences itself as the entire world. While every lifeform has to interact with the environment--to obtain nutrients, for example, and often to avoid predators--in these lifeforms the interactions are minimal, and are usually achieved at the cellular rather than the organism level. Thus plants, sponges, and many Coelenterates are sessile, and feed passively, taking their food as it comes to them rather than pursuing it. So I claim that whatever awareness or interiority such organisms have (and like Wilber, I believe all forms of existence have some interiority), to a large degree it does not distinguish between the organism itself and its surrounding environment. In summary, then, there are lifeforms that have virtually no active, subjective interaction with other members of their species or even with their environment, and which therefore cannot possibly, by any definition of the term I know of, be embedded in any intersubjective relationships. Furthermore, lest anyone think such lifeforms are a rare exception to the general rule, let me add that they are found at every level of existence. Not only are there very primitive, asocial organisms on our level of existence, but there are primitive, asocial cells on the level below it, and primitive, asocial atoms on the level below that. Examples of such cells are many unicellular organisms, and examples of such atoms are inert varieties like helium and xenon. According to my model, these lifeforms, too, have zero-dimensional experience, not distinguishing between self and other. So one objection I have to Wilber's claim that intersubjectivity is found everywhere in the cosmos is that sociality, which is a prerequisite to intersubjectivity, is not found everywhere. In fact, the bottom or fundament of every level of existence is made up of asocial holons which make no self/other distinction and which therefore do not exist within an intersubjective framework. So every level of existence has a portion into which intersubjectivity does not penetrate. Intersubjectivity can only emerge when fundamental holons begin to associate into social holons, forming the higher stages of the holarchy. The second objection I have is that among the majority of lifeforms that do exist within intersubjective structures, these structures are very different from the kind we live within. A detailed explanation of this problem is beyond the scope of this article (see Smith, in preparation), but the argument can be sketched very simply. An essential feature of our experience of the world, a fundamental strand in our intersubjective framework, is the dimension of time. We have a very well-developed sense of time, which allows us, among other things, to perceive both other organisms, including other members of our species, as well as other objects, as having a permanent existence. For example, we believe that a certain tree exists (as well as trees in general) even when we are not actually experiencing the tree directly. We have this belief because we are capable of experiencing the tree not only in space but also in time. We carry this experience around with us even when there are no trees physically present. Because we do, we not only believe in the existence of trees when we aren't experiencing them, but our experience of them even when we actually do see them is at least partly of this permanent belief. For even when we seem to be "directly" experiencing a tree, what we are actually experiencing is a concept of one. Wilber puts it this way: It is not that there is experience on the one hand and contextual molding on the other. Every experience is a context; every experience, even simple sensory experience, is always already situated, is always already a context... So the human intersubjective framework is created almost entirely of experiences, or concepts, of phenomena that we are not actually experiencing directly.. Even when we seem to be experiencing objects or events directly, we really aren't, in an important sense. And to reiterate, we can have these concepts only because we are capable of experiencing phenomena over time. Without a sense of time, there is no understanding of other objects or organisms as having a permanent existence. But many lifeforms have relatively little sense of time. They do not have much experience of other organisms or objects as existing when they are not in direct contact with them. How do we know this? The traditional test for a sense of time is the ability to learn and remember. It's true that many invertebrates, including some fairly simple ones, have been shown to exhibit certain rudimentary forms of learning, such as habituation, and classical or operant conditioning (Peeke et al. 1965; Evans 1966; Ratner 1972; Ratner and Gilpin 1974; Haralson et al. 1975; Taddei-Ferretti and Cordella 1976; Lockery et al. 1985; Debski and Friesen 1985; Sahley and Ready 1988; Karrer and Sahley 1988; Johnson and Wuench 1994). This suggests that they may have some concept of external objects or events that affects their perception or experience of them. But the same studies, and numerous ones that have failed to demonstrate many kinds of learning, also indicate that such concepts, if we may use that word loosely, are far less developed than our own. Invertebrate learning studies have to be designed with some care, just because the ability of these lifeforms to learn is so limited. In other words, in these organisms, the relationship of subjectivity to intersubjectivity is much weaker than it is for us. It's not just that subjectivity or interiority is much weaker in these lifeforms, a point Wilber and I are in complete agreement on. It's that whatever subjectivity there is is far less dependent on, or created by, intersubjective relationships. To state a more general point that I discuss in more detail elsewhere (Smith, in preparation), the higher in our level (or in any other level) a lifeform is, the greater the degree to which its subjectivity is molded by intersubjective relationships. This goes back to the point I made in an earlier discussion, that higher stages within levels are characterized by more interactions among individual holons, for it is in fact these interactions that constitute the intersubjective network or structure (a point I will discuss further shortly). So in addition to there being some lifeforms on every level that have no intersubjective relationships, the degree of intersubjectivity among those that do varies substantially, according to the position of the lifeform on the level. I think this is an important modification of Wilber's views. To reiterate for emphasis, it's an oversimplification to say that subjectivity (or interiority) and intersubjectivity both increase as we move up the holarchy. While subjectivity does increase, intersubjectivity increases only within any particular level. When we move to a new level, there is initially no intersubjectivity; it's gradually created as the level develops. And the lower, weaker forms of intersubjectivity found on every level are characterized by a much weaker input into the subjectivities that constitute, or emerge from, them. In conclusion, then, I have two major objections to Wilber's claim that intersubjectivity is found everywhere in the holarchy. Both of these objections, the reader will note, stem directly from differences in our models of holarchy. My model, as I discussed earlier, distinguishes between stages and levels, and defines stages in terms of increasingly complex social organization. Thus even within any level of existence, there is a holarchy of lifeforms, some ranked higher than others. Furthermore, a key distinguishing feature of this holarchy-within-a-level is dimensionality. Higher lifeforms on any level exist in more exterior or structural dimensions than lower forms, and also in their interior or experiential features. These differences in dimensionality, in turn, are a key to a more detailed understanding of intersubjectivity. This view a) recognizes the limits as well as the extent of this phenomenon; b) illuminates just how intersubjectivity differs in different lifeforms; and c) though not discussed here, provides us with a key tool for understanding how these different degrees of dimensional interiority evolve (Smith, in preparation). Before concluding this discussion of intersubjectivity, I want to address another aspect of Wilber's view of it, which again I believe reflects limits of his model. This is the relationship intersubjectivity has with subjectivity. I just argued that in the lower stages of any level, this relationship is weaker than it is for higher stages. But what is this relationship like in general? Exactly what is it that becomes stronger as we move up any level of existence? According to Wilber's postmodern insight, intersubjectivity is ontologically prior to subjectivity. That is, individuals do not create intersubjective relationships, but on the contrary, individuals are themselves created by an intersubjective structure or matrix that precedes them:

One of the great discoveries of the postmodern West is that what we previously took to be an unproblematic consciousness reflecting on the world at large...is in fact anchored in a network of nonobvious intersubjective structures. Sean Hargens, a follower and interpreter of Wilber, explains the relationship of intersubjectivity to subjectivity further:

[T]he subject is embedded in a field of relationships and...both subjects and objects arise out of that field...I'm created by you and others (in a shared background context) before we even engage. Two claims are being made here: 1) intersubjectivity is ontologically prior to subjectivity; and 2) the matrix or structure or field that constitutes or creates intersubjectivity is not accessible to the subjects, i.e., we can't actually experience or be aware of this structure. These claims are closely related, perhaps are just one claim, because to say that a structure or field is ontologically prior to our individual subjectivity seems to imply that we can't directly know this field. Described in this way, intersubjectivity has, to me at least, a mysterious, almost magical, quality to it. If it's ontologically prior to our individual subjectivities, where did it come from? How was it created? And would it continue to exist in the absence of these subjectivities? Hargens, in an article contrasting Wilber's views on intersubjectivity with those of Alfred North Whitehead, further explains:

But for Wilber, the intersubjective space is more than just an acknowledgment of the objective nature of a subject-subject interaction. Wilber sees the intersubjective space as the background that gives rise to the subject, regardless of whether it entered as an object. After all, as Wilber explains, "as the new subject creatively emerges, it emerges in part from this intersubjectivity, and thus intersubjectivity at that point first enters the subject as part of the subject, not as an object-that-was-once-subject." This is the key point: the subject is actually composed of aspects of the intersubjective space, even before it prehends anything (e.g., other subjects as objects). Thus there is a dialogical relationship between the subject and intersubjective spheres even before the monological relationship between the subject and object occurs. To illustrate this point, Wilber gives the example of someone being at a post-conventional stage of morality. At this stage of moral development, an individual will have thoughts arise within that space (of moral development), but the structure of this post-conventional stage was never an object. However, this stage of development does form part of the structure/space from which the new subject arises moment to moment. Therefore, this structure enters "the subject as prehending subject, not as a prehendedobject that was once subject."[11] Let me try to reinterpret this notion a little. In fact, in the following discussion, I will attempt to accomplish two objectives,simultaneously. One, I will provide examples of intersubjectivity as they occur on lower levels of existence. And two, I will use those examples to illuminate the relationship of intersubjectivity to subjectivity in general. For while there may be truth to Whitehead's claim that:

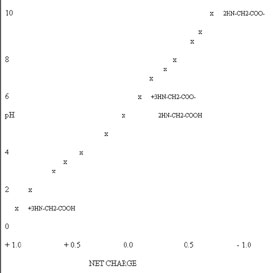

if you want to know the general principles of existence, you must start at the top and use the highest occasions to illumine the lowest, not the other way around. it's also true that we can often see a phenomenon better on a lower level, where we have a more objective relationship to it. I argued earlier that lifeforms experience their world in different degrees of dimensionality, with the lowest holons on any level realizing zero-dimensional experience, in which no self/other distinction is made. Let's now consider an example of one-dimensional experience. On our (mental or behavioral) level, this kind of experience is exemplified by some fairly simple invertebrates such as Annelids (segmented worms), Nematodes (round worms) and primitive Gastropod Molluscs (snails and slugs). These organisms are the lowest ones to have bilateral symmetry, in which an anterior/posterior distinction is made, and they are capable of making intensity discriminations among certain stimuli, such as light, touch and some chemical substances. Thus as I have discussed elsewhere (Smith, in preparation), these organisms perceive their world as a one-dimensional axis, on which they are situated. The same kind of experience is found on lower levels. Consider the physical level, consisting of atoms and molecules. As I mentioned earlier, zero-dimensional experience is typical of inert atoms like helium, which do not form chemical bonds with other atoms. Like zero-dimensional organisms, they have no social or communicative relationships with others of their kind.[12] This is also approximately true for reactive atoms, those that do form chemical bonds with other atoms, when they exist in the free or unbonded state.[13] However, as soon as reactive atoms bond and form molecules, the next stage on the physical level of existence, full one-dimensional experience emerges . Consider an amino acid molecule, a fundamental component of all living cells (Fig. 1). Notice that the molecule is both linear and asymmetrical, or as chemists say, polar. It has a different group of atoms at one end from the group at the opposite end. The polarity of the molecule becomes even more pronounced when one or both ends carry an electrical charge, as a result of gaining or losing a hydrogen ion (H+). 2HN-CH2-COO- +H+ —> 2HN-CH2-COO- OR +3HN-CH2-COO- +H+ —> +3HN-CH2-COOH Fig. 1. An amino acid can exist in several different charge states, carrying positive and/or negative charges. An amino acid molecule, therefore, should experience itself as one dimensional, able to discriminate the world differently at its two ends.14 This is analogous to one-dimensional organisms, that have an anterior and posterior end, and which can discriminate their environment in front of them from that in back. These two ends of the amino acid can in fact behave like rudimentary sensory receptors, sensitive to the pH in the medium (see Fig. 2). The amino or nitrogen end (H2N - +H3N) detects pH values in the range of 9-10. If the pH is above 10, the amino group will lose a hydrogen ion to form H2N. If the pH is below 9, the molecule will gain a hydrogen ion to form +H3N. The carboxyl end (COOH), on the other hand, will gain a hydrogen ion when the pH is below about 2, and will lose a hydrogen ion when the pH is above 3.

Fig. 2. Variation of net charge on an amino acid (as indicated by "X"s) with pH. As explained in the text, this relationship allows the amino acid, and some atoms within it, to detect the pH, and also allows some atoms to detect the charged state of other atoms within the molecule. Notice that this is an intensity discrimination, quite analogous to that made by primitive invertebrates. The amino acid distinguishes different concentrations of hydrogen ions, a one-dimensional form of perception. The concentration of hydrogen ions varies along a single axis, just as sensory stimuli such as light do, and the amino acid can determine where on this axis the concentration lies. This is a one-dimensional experience. So far, we have considered the amino acid molecule as a whole. But its one-dimensional experience is also realized by some of its component atoms. Consider the oxygen atom that hydrogen interacts with at one end of the amino acid (the carboxyl end). As shown in Fig. 1, the oxygen atom sometimes carries a negative charge, when it is not interacting with a hydrogen ion, and sometimes does not carry a charge, when it is interacting with hydrogen. What determines whether it does or does not? The pH of the surrounding medium, as noted earlier, but also the ionization state of the nitrogen atom at the other end. As can be seen in Fig. 2, the oxygen atom will have a negative charge when a) the pH is greater than 10; or b) the pH is between 3 and 9, and the nitrogen atom at the other end of the molecule is protonated. Conversely, oxygen will carry no charge when a) the pH is below 2; or b) the pH is between 3 and 9 and the nitrogen is not protonated. Therefore, the oxygen atom a) can also make an intensity discrimination, determining the pH or hydrogen concentration of the surrounding medium; and b) has information about the state of the nitrogen atom at the other end of the molecule. It experiences not only what is going on at its end of the molecule, but also what is going on at the other end. Thus the oxygen atom, like the amino acid as a whole, has one-dimensional experience. We can say that it has this experience because it participates in the one-dimensionality of the amino acid molecule. It's only possible for an individual atom like oxygen to have one-dimensional experience when it's bonded to other atoms within a molecule. Its association with these other atoms allow it to have higher-dimensional properties that would otherwise be unrealizable for it.15 This most rudimentary example, far removed from human beings interacting by means of language or other forms of communication, makes an important point about the relationship of intersubjectivity to subjectivity. If we buy into the premise that even atoms and molecules have experience, or interiority, the amino acid is clearly the intersubjective structure in which oxygen and other atoms function. It's analogous to the intersubjective structure formed by a group or society of one-dimensional organisms. Even before it becomes part of this molecule, the oxygen atom can have experience, but upon bonding to the other atoms, the nature of its experience clearly changes. It goes from zero-dimensional or partially one-dimensional to fully one-dimensional. Its experience also becomes intersubjective because--as is the case with higher level organisms--it engages in communication with other holons of its kind, and its own experience of self is shaped to a large degree by this communication. That is, how the oxygen experiences itself--as an atom capable of gaining or losing a hydrogen ion--changes when it interacts with other atoms. Just as one-dimensional experience on the physical level emerges with simple molecules, one-dimensional experience on the biological level emerges with simple tissues, or groups of cells. We can find examples of such tissues in almost all organisms; for example, nervous ganglia, which function as a primitive brain in many invertebrates, and carry out various lower-level functions in vertebrates. A ganglion consists of several thousand or more highly interconnected cells, which act as a unit in receiving inputs from sensory organs or other neurons, and/or in transmitting messages to effector organs or other neurons. Like an amino acid, a ganglion has polarity; it may receive input at one end, and transmit output at the other, or it may do only one or the other, at one end. A ganglion is also capable of intensity discriminations. When it receives sensory input, for example, it responds according to the degree of stimulation. Individual neurons within a ganglion may likewise participate in these one-dimensional properties. Recordings from individual cells often reveal that they can make intensity discriminations, altering their firing pattern in response to changes in the stimulus coming into the ganglion. Likewise, such cells have information about the activity of other cells, changing their activity in response to changes in activity in other cells. Such higher properties result, just as they do with atoms in the amino acid, because the neurons are able to communicate with one another, and thus receive information that would otherwise not be accessible to them. In summary, intersubjectivity results whenever fundamental holons--atoms, cells or organisms--join together into higher-order social or intermediate holons. The latter form the intersubjective structure--a network of highly connected fundamental holons--that gives rise to new properties of higher dimensionality. In the case of one-dimensional structures, these properties include the ability a) to make intensity discriminations amongcertain stimuli in the environment; and b) to interact with other fundamental holons at a distance, i.e., which are not physically adjacent to itself. Higher-dimensional social holons have higher-dimensional properties, which can also be experienced by their component individual holons. Notice that we now have a clearer idea of not only what an intersubjective structure is, and its relationship to individual subjectivities, but also why it is ontologically prior--and experientially inaccessible--to the individual subjectivities. This simply reflects the fact that social holons are higher than their individual components. The molecule, which in my model is a social holon, is higher than the atom; the tissue is higher than the cell; and human or animal societies are higher than their individual members. Wilber recognizes that lower order holons in general can't perceive or experience the nature of higher-order holons, but as I discussed earlier, he maintains that social holons (as he defines them) are not higher than their component individual holons. Yet as this discussion should make clear, it's precisely because social holons are higher than individual holons that the intersubjective structure is not experienced or "prehended" by the latter. Wilber is being logically inconsistent when he maintains, on the one hand, that intersubjectivity is ontologically prior to subjectivity, and on the other hand, that societies are not higher than their individual members. Societies, if not identical to the intersubjective structure, are obviously very closely related to them; the two are on a holarchical and ontological par. The one-scale model, by emphasizing this point, helps illuminate the relationship of intersubjectivity to subjectivity.

The Limits of the IndividualAnother area where my view of the relationships between exterior and interior, and individual and social, leads to very different implications from Wilber's is perhaps of the most interest and relevance to those who follow Wilber: it concerns how we are to understand how individuals can develop to a higher state of being. As noted earlier, Wilber views the individual and the social as "two sides of the same coin", neither higher than the other. This tends to promote or encourage what I consider to be a false view of individual power and individual action. Let's see how this comes about. Most theorists recognize that a primary criterion by which we distinguish the holarchically higher from the lower is the presence of new, emergent properties. Thus molecules have properties not exhibited by individual atoms, cells have properties not observed in molecules, organisms have properties beyond those of their cells, and so on. Now it's patently obvious that societies also have such emergent properties, ones not found in their individual members, so by this criterion (and others), as I have argued elsewhere, we must regard societies as higher than their members (Smith 2000a; 2001 a,c). Wilber and his supporters, to counter this argument, must take the position that while societies do have some properties not found in their individual members, the reverse is also true. Individuals have properties not found in societies. As an example, they point to great visionaries who have shaped the destiny of societies (Goddard 2001). The implication seems to be that while societies are beyond us in some respects, we are beyond them in others, so neither can be said to be higher than the other Now even if we ignore the obvious asymmetry still exposed by this reasoning (any society has many properties not found in any of its members; only rare individuals are alleged to have one property not found in the rest of society), this assertion ignores the vast amount of social influences on any individual. No scientist, artist or even mystic lives in a vacuum; their methods as well as results depend critically on a wealth of interactions from other people. Furthermore, just because one individual, on rare occasion, may come to some experience, accomplishment, or idea that no one before has, it does not mean that this realization is not a social property as much as an individual. In fact, there are very few properties that all individuals in a society have. There is rather a continuum, beginning at one end with properties that are universal or nearly universal (e.g., the ability to walk, use language and feel certain basic emotions) to less common abilities (run a four minute mile or understand string theory) to unique or nearly unique abilities (Shakespeare's plays; Einstein's theories). There is no apparent justification for selecting properties at the far end, and saying that they are strictly individual accomplishments. There is no rule saying that social properties have to be manifested in every member of society, or even in most members. Yet Wilber's four-quadrant model strongly implies that individuals can have properties that are, so to speak, "separate but equal": independent of society yet on the same level.16 This view, applied to the goal of realizing higher consciousness, leads to the notion that this involves to a large extent a purely individual effort. It may be partly why Wilber has been criticized for not emphasizing more what has been called the social or collective aspects of spirituality, practices that involve directly relating to others (Edwards 2001). However, the symptoms of Wilber's view of the individual lie deeper than this. Wilber may not emphasize the social aspects of spirituality as they are commonly conceived, but he does recognize them. His model certainly has room for them, and permits others to develop the implications. What he does not recognize--and he has a great deal of company here, which has helped to maintain his view unchallenged--is the extent to which spirituality involves the social dimension. It is generally far more important than the individual dimension. This is an extremely common misunderstanding, I believe. Even people who celebrate compassion, charity, good works, and other activities directed towards helping others believe that there is a major individual aspect to spirituality. After all, when we withdraw to meditate--perhaps even doing so in a lonely retreat--isn't it all about the individual? A self trying to realize a higher Self, to be sure, but for the time being just an individual self? The answer is no. Meditation is the struggle with our thoughts and desires, and most of these represent bonds, constraints, placed upon us by virtue of our membership in societies. This means that no matter how withdrawn from direct interaction with society a meditator may be, she is still very much engaged with it. There are, to be sure, individual elements that arise or can arise during meditation. If one fasts, for example, the struggle is directed against a desire that is in principle purely asocial. And there are spiritual paths--from Christian self-flagellation to Hindu fakirs--that emphasize the struggle against such basic desires. But even in such extreme cases, the struggle is not confined to such desires, because any human being has other, socially-derived desires--from simple one such as the need to talk to more complex ones involving specific experiences made possible only by society--and these will eventually come up, not only when one is not directly confronting a basic desire, but even during such ordeals, as one adapts to the stress of denial. Ken Wilber, to his great credit, recognizes this--it's what his Integral Psychology or Practice is all about--even if he does not in my view recognize how much these other desires result from our being situated in social holons. Meditation, then, is the struggle is not simply with oneself, but in a very profound sense with the entire world. This is why meditation is so extraordinarily difficult, why it is impossible by all ordinary human standards. Because we are not just testing our own, personal limits. We are up against something almost incomprehensibly vaster than any individual self. Gurdjieff was one of the very rare teachers who seemed to understand this, who emphasized that the nature of this relationship may even place limits on the number of people in any era who can realize higher consciousness (Ouspensky 1961). That so very few other teachers or mystics have even suggested the possibility, but seem to assume that everyone can realize a higher state of awareness, surely speaks to how underappreciated is the relationship of meditative efforts to social constraints. As far as I know, no investigations of meditation are attempting to explore this area. While Wilber has cited data indicating that relatively few people realize higher states of awareness (Wilber 1998)17, there seems to be little or no effort directed to answering the question of why this is so. Yes, meditation is very difficult, but why is it difficult? What's going on? Elsewhere (Smith 2000c) I have pointed out that meditation is a process of acquiring energy, and that there are limits to how fast this process can occur. But in addition to limits on the rate of the process, there may also be limits on how often the process can take place. It's my claim that social constraints are a major factor in these limits, that any kind of society can only support, or tolerate, a limited number of people in a higher state of awareness. I have discussed some of the reasons for these limits elsewhere (Smith 2000a).

Interior/ExteriorOne of Ken Wilber's strongest and most insistent criticisms of modern knowledge, including most of science and philosophy, is that it ignores the interior properties of existence, the capacity holons have for experiencing the world. His four-quadrant model addresses this problem by making the distinction between interior and exterior properties of holons, at every level of existence. According to him, every holon has both aspects, and neither can be reduced to the other. I have already pointed out that my model differs in that interiority to a large degree is not distinguished in this way from exteriority. The two are found on the same axis. What's my rationale for this? Surely we have to begin this discussion by defining just what we mean by interior properties. Anyone who has read much of Wilber can be forgiven for not being sure what his definition is. When he contrasts interiors with the exteriors that science studies, he seems to be equating the former with consciousness (at least on our level of existence), and more specifically to what philosophers refer to as qualia, the purely experiential properties or "hard problem" of consciousness (Chalmers 1996). If this is indeed what Wilber means by interiority, I believe his distinction is valid. Though some philosophers and probably most scientists think that consciousness in this sense is ultimately explainable in terms of physical and biological processes--exteriors in Wilber's model--no one has been able to develop a theory or model of any kind that demonstrates how such a relationship is possible. Indeed, this problem is so intractable that panpsychism, the long discredited belief that consciousness or awareness in some sense is a fundamental property of all forms of existence, even the lowest, has been making a comeback among an important minority of philosophers, precisely because it suggests a way out of this dilemma (Lockwood 1991; Chalmers 1996; Griffin 1998; Sprigge 1999; Seager 1999). Though a discussion of this topic is beyond the scope of this article, panpsychism, at least in some forms, appears closely allied with Wilber's view of an interior/exterior distinction that is maintained throughout the holarchy. So one could say that mainstream philosophy is beginning to catch on to some of Wilber's ideas. However, that Wilber's view of interiority is not limited to consciousness in the "hard" sense is suggested by other discussions in which he uses the term in a broader way. For example, in Sex, Ecology, Spirituality, he describes interiority as being exemplified by the difference in the experience of two people in a foreign country, one who is familiar with the language, and one who is not. While certainly these two individuals will have different interior experiences, I don't believe that this example captures the essence of the hard sense of consciousness. To appreciate this, we need only observe that the activities of neural structures--what Wilber clearly defines as exteriors elsewhere--contribute to whatever differences the individuals experience. Most scientists and philosophers-- including Wilber, I think--would agree that in principle if not in practice we could identify these structures, and by stimulating them appropriately recreate the experience of understanding a foreign language. This doesn't prove that these neural processes cause the experience, because it can always be argued that there are other factors involved that we aren't aware of. I agree with Wilber that all we can say here is that the neural processes are correlated with the experience (I will discuss the concepts of corrrelation and cause further later). But this kind of thought experiment does strongly indicate, I think, that these neural processes, these exteriors, cause the differences in experience that the individuals have. In other words, I think Wilber has it backwards here. None of the differences in experience between these two individuals in a foreign country reflects consciousness, or interiority, in the hard sense. Consciousness in this latter sense, it seems to me, must be the same for the two people, indeed for any two people. That is, if we subtract out, so to speak, all the differences contributed to by exterior structures--the differences in the sounds that the two individuals pay attention to, the differences in the way they process the sounds they hear, the differences in recall of certain memories and other forms of knowledge, and so on--what exactly are we left with? We are left with just experience, nothing more, nothing less. This is consciousness in the hard sense, the slippery but very real phenomenon that eludes all attempts to explain in terms of physical and biological processes.18 Further confusion, or at least vagueness, arises when Wilber applies the term to lower levels of existence. At this point, it's not clear that he is equating it with any form of consciousness. Sean Hargens' reading of Wilber is that he is is in basic agreement with Whitehead's view of lower interiors as prehensions, in which a subject prehends or "touches" an object (Hargens 2001a). But without getting into a discussion of Whitehead, a very difficult philosopher to understand, it seems to me that Wilber again falls into the habit of describing interiors in ways that sound very much like exteriors. Thus he defines the interior of a cell as "protoplasmic irritability," and that of an electron as a "propensity to existence". Most scientists would say that these phenomena have been or can be explained in terms of physical processes. Wilber also says of atoms that they have

depth, and therefore they do share a common depth. And a common depth is a worldspace, a worldspace created/disclosed by a particular degree of shared depth.[19] Perhaps I'm missing something, but what I read in that statement is just that atoms share certain properties, therefore these properties constitute a space. The fact that these properties are "depth" is meaningless to me, because Wilber has not defined depth except in terms of other words that are approximate synonyms for interiority, consciousness, or the like. He seems to be going in circles here. Thus Hargens concludes rather soberly: Wilber admits that when you try to describe the interiors of the lower levels you cannot make any strong claims as to what they consist of; he just wants to acknowledge that they are there. Well, I do, too, but I can't blame others for not agreeing with me if I not only can't prove that they're there, but can't even say what these things are like that I claim are there. Finally, as though to make sure that all possible bases have been touched, Wilber announces that consciousness is in fact everywhere: "in the conventional or manifest realm, consciousness appears as all four quadrants". Frank Visser, with the evident approval of Wilber, puts it this way: "consciousness is not completely dependent on the four quadrants for its existence but uses them to express itself."[20] If we are to say that consciousness is expressed in all four quadrants, then it seems to me we are using this term differently from the way philosophers and scientists commonly mean it (hard or soft sense)--or alternatively, we are adopting a form of idealism, in which consciousness creates what we understand as the material world. Is there any way we can make sense out of all these blind-men-and-the-elephant descriptions of interiority? In my model, I distinguish between the functional or "soft" aspects of consciousness and the experiential or "hard" aspects. This distinction is accepted by a very large consensus of philosophers and scientists, I think, and those who do are virtually unanimous in their belief that the functional aspects can and ultimately will be explained in terms of molecular and cellular processes in the brain--in other words, what Wilber calls, sometimes but not at other times, exteriors. If we accept this claim, then there should be no problem in representing these aspects of consciousness, or "soft interiority" to speak loosely, on the same scale or quadrant with holons that Wilber always refers to as exteriors--atoms, molecules, cells and so on. This is precisely what my one-scale model does. As I noted earlier, interior qualities of this kind are combined with exterior structures. As also pointed out before, this way of arranging things draws attention to the fact that interiors at any particular stage are not simply correlated with particular exteriors, but bear certain relationships to them, some of which are known and which I have discussed earlier here and elsewhere, and some of which remain to be elucidated. This does leave out, however, the hard aspects of consciousness, which philosophers usually refer to as qualia. The way the one-scale model handles these is to postulate that there is an ultimate or ground consciousness, as Wilber would put it, which is accessible to every holon to just the degree that it has evolved in the holarchy. This view of consciousness, it seems to me, has some affinity with the previously quoted interpretation of Wilber's view: "consciousness is not completely dependent on the four quadrants for its existence but uses them to express itself". That is, I agree that consciousness uses the holarchy to express itself (or perhaps it would be better to say it expresses itself in holarchy). But having said that, why do we need four quadrants? Why not just say that consciousness expresses itself in the exterior forms of holons, and to the extent that it does so at every level, the holon experiences consciousnessness or interiority, in the hard sense? We could speak of two axes or quadrants here, but since the degree of interiority in this sense parallels the degree of development of exteriors, there doesn't seem to be any need to. Thus we have more interiority than other mammals, which have more than invertebrates, down to cells, and so on. I mean this is in a rigorously quantitative sense. I think we can, in theory, say just how much or how many times more conscious we are than other forms of life, an idea found in Gurdjieff's work (Ouspensky 1961) that I discuss at length elsewhere (Smith, in preparation). This view of interiority, like Wilber's, is open to the concept of panpsychism, the belief that all forms of existence, even simple matter, has some consciousness, however dim. But whereas most panpsychists would probably claim that the highest forms of consciousness--our own and whatever levels are beyond us--are built up from below, through evolution of dimly conscious matter to more conscious life and still more conscious mind, in my model consciousness comes from above. That is, rather than saying that consciousness or interiority is an inherent property of matter, I would say that what is inherent is the expression of a certain degree of ultimate consciousness. Wilber and his followers ought to be symapthetic to this view, because it explicitly rejects the idea that higher forms of existence evolved from nowhere or nothingness. The higher is always present, and evolution is seen as a gradual return. In concluding this section, I want to point out another apparent logical inconsistency in Wilber's model. As noted earlier, the four-quadrant model posits that interiors and exteriors are different aspects of the same holon, and therefore any particular interior/exterior pair exists on the same level. In my model, interiors are frequently (though not always) higher than exteriors. This follows from the arguments that 1) social holons are higher than their individual holon members; and 2) the interiority of individual holons, when they are found within social holons, often shares much of the latter's properties, through participation of the kind I discussed earlier. Elsewhere (Smith 2001g), I have discussed many arguments against Wilber's view of interiority and exteriority's being on the same level. Here I want to point out that--just as we saw in the previous section with regard to the social/individual relationship--Wilber elsewhere maintains a position that clearly contradicts his own view. This is illustrated in the following quote from Hargens: the relationship between mind (concepts) and body (feelings) [is] one of "transcend and include," where mind transcends and includes body...Wilber agrees and points out that this is another way of saying that the subject contains the object (thesenior level contains the junior level) but the object does not contain the subject (the junior level doesnot contain the senior level).[21] We all seem to agree that subject = mind transcends and includes the object = body.[22] Why, then, is there any problem in understanding that interiors are higher than exteriors? Isn't the subject an interior, and the object an exterior? How much clearer a statement of this relationship can one have? Do Wilber and his supporters actually listen to what they are saying?