|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Rolf Sattler, PhD, FLS, FRSC, is an emeritus professor of McGill University in Montreal, Canada. His specialty was plant morphology: the development and evolution of plant form. Besides plant biology and general biology, he taught courses in the history and philosophy of biology. Furthermore, he explored the relation between science and spirituality. In this connection, he taught a course at Naropa Institute in Modern Biology and Zen and participated in several symposia on Science and Consciousness. He published nearly 80 research papers in refereed scientific journals and is the author of several books including Biophilosophy: Analytic and Holistic Perspectives (1986) and an e-book Wilber's AQAL Map and Beyond (2008), published at his website www.beyondwilber.ca, which also includes a book manuscript on Healing Thinking and Being that examines ways of thinking and different kinds of logic in relation to human existence. His latest book that he also published on his website is Wholeness, Fragmentation, and the Unnamable: Holism, Materialism, and Mysticism - A Mandala. Rolf Sattler can be reached through his website www.beyondwilber.ca Beyond

Materialist Science

A Response to Steve Taylor, Frank Visser, and David Lane

Rolf Sattler

We can go beyond materialist science and still remain scientific in one sense or another.

Science has been and can be defined and understood in many different ways. Understanding it in materialist terms as materialist science is only one way among others. Probably for historical reasons, it is the most common way in our mainstream society. In fact, many scientists and laypersons equate science with materialist science. Hence, if it is not materialist, it is not science. Philosophers of science and those who have thought much about science and have practiced it, do not necessarily subscribe to such a narrow view because the philosophy of science appears very rich and complex. Here I want to draw attention to some of these issues as a response to a recent debate on this website concerning spiritual and materialist science [1,2,3,4,5]. I have dealt with the complexity of science much more comprehensively elsewhere [6].

Scientific Explanation and Prediction

Instead of defining science as materialist, science has often been understood in terms of explanation and/or prediction. Thus, a theory is scientific if it allows explanations and/or predictions. Whether the theory is materialist or non-materialist does not matter. As long as it allows explanations and/or predictions it is considered scientific. Besides many materialist theories, there are also non-materialist theories or theories that go beyond matter that yield explanations and/or predictions.

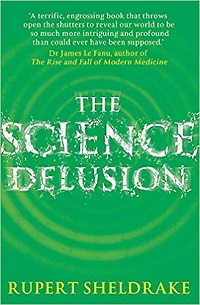

An example is Rupert Sheldrake's theory of morphic fields and resonance [7]. It allowed, for example, to explain and predict that when certain species of animals learn a new behavior it is easier for animals of the same species far away to learn the same behavior [7]. Thus, physical contact or proximity is not necessary. The transmission occurs through morphic fields and resonance. In addition to this phenomenon, Sheldrake's theory allows predictions and explanations for many other phenomena [7]. Materialist science has not yet provided satisfactory explanations for these phenomena. And there are other areas such as consciousness and psychic phenomena where so far materialist science has failed [7,8]. One common response by materialists is that they believe and hope that in the future all of these failures will be resolved through materialism. In this sense materialism has become a belief system, a dogmatic religion or pseudo-religion [1].

Another restriction is David Lane's insistence that “we should fully explore and exhaust physical explanations first” [5]. I prefer openness to faith and David Lane's restriction because openness may lead to greater insight. People who dogmatically insist that all science has to be materialist or that “we should fully explore and exhaust physical explanations first” [5], do not appear sufficiently open to the exploration of alternatives. They may also be unaware of alternatives that work or denigrate them. Let's look at alternative medicine as another example of alternatives to the materialist approach.

Alternative Medicine

One alternative to the common materialist medicine is acupuncture that is based on a subtle energy or vital force called chi. Much healing has been and can be accomplished through acupuncture. Of course, acupuncture does not work for all ailments, but neither does conventional medicine that is based on materialism and mechanism. Thus, instead of engaging in endless arguments for and against acupuncture and conventional medicine, it seems more profitable to consider the two complementary. I find it encouraging that now some medical schools even offer courses in acupuncture. Materialists might argue that eventually acupuncture and Chinese medicine might be completely understood in material terms. So far the foundations of the two a very different because Chinese medicine implies a non-material life-force. Frank Visser [2] wrote that “if we still believed in the life-force, we would not have had DNA.” But we can have both, the life-force or subtle energy and DNA. They need not be seen as mutually exclusive but as complementary. Together they provide a richer view of reality than only one or the other.

Complementarity

In general, materialist science and science that transcends it need not be seen as antagonistic opposites but rather as complementary [9]. Unfortunately, Aristotelian either/or logic is still deeply entrenched in our mainstream culture and science. The extreme consequence of this kind of thinking is “I'm Right and You're an Idiot” [10]. We have to learn to appreciate the value of complementarity. To illustrate complementarity, I used a mountain analogy [11].

With regard to reality, two opposite views have been distinguished. According to one, matter is fundamental and primary and maybe all there is; mind or consciousness may be only an epiphenomenon. According to the other view, consciousness is fundamental and primary, and matter is a derivative of consciousness or may be inherent in consciousness. In the latter case, if matter is inherent in consciousness, the debate about whether matter or consciousness is primary may be transcended. In that case one might also say that both matter and consciousness are fundamental, or matter and consciousness may be aspects of a deeper reality.

Materialist science usually tends to imply that matter is primary or all that exists, whereas non-materialist or spiritual science tends to consider consciousness as primary. Obviously materialist science has been successful in many ways. But it has failed to understand mind and consciousness and many phenomena such as parapsychological phenomena related to them. On the other hand, non-materialist or spiritual science (including science that considers both consciousness and matter fundamental), can understand at least to some extent consciousness and phenomena related to it. If it can enlarge its scope so that it could deal with all phenomena, it would be the most comprehensive science. Although such a science would have transcended materialistic science, it would include its accomplishments.

However, before such a comprehensive science will be developed (if it ever will), it might be best to consider materialist and non-materialist science as complementary avenues towards a better understanding of reality. Together they achieve more than just one alone. This means that with regard to the recent debate on spiritual science (on this website) we may recognize a complementarity of materialist science and spiritual science as conceived by Steve Taylor[1]. Obviously non-materialist or spiritual science may have different versions and those versions again may be considered complementary. Being complementary does not necessarily mean that they are equally valid. One might be more comprehensive than the other. But even a far less comprehensive one might still illuminate some situations with which the more comprehensive one cannot deal [11]. Also, any version may be partially wrong. To be 100% wrong seems nearly impossible, as Ken Wilber remarked.

The Semantic View of Scientific Theories and Laws

In this connection, the semantic view of theories and laws becomes highly relevant. As explicated by Giere [12], according to this view, theories and laws are definitions. The question then is no longer whether they are right or wrong. The question is whether they apply in any particular instance. The more often they apply, the better. But if a theory or law applies only to few instances in which the more comprehensive theory or law does not apply, it is still useful. Again, these theories and laws can be considered complementary. I have given some examples in my essay on Science: its power and limitations [6].

Scientific Methodology

I doubt that anything goes, but from my own experience as a scientist I know that many things go, much more than most scientists can imagine.

Instead of defining science as materialist, it has often been understood in terms of its method, which therefore has been called the scientific method. This method does not specify that science has to be materialist. As long as this method is applied, it is science. The problem is that if you study the literature on the scientific method you will find that there is no agreement what exactly this method is. Feyerabend [13], who knew the history of science very well, even concluded that there is no scientific method and therefore he coined the slogan that in science anything goes.

I doubt that anything goes, but from my own experience as a scientist I know that many things go, much more than most scientists can imagine. The lack of imagination, conservatism and other factors have often been an obstacle to progress. Just look at the history of science. So often fundamental innovations have been tenaciously resisted by the majority of mainstream scientists.

Paul Feyerabend: “Anything goes.”

Paul Feyerabend: “Anything goes.”

And such resistance continues. For example, the medical establishment resists and often actively suppresses alternative healing methods such as energy healing or spiritual healing or even herbal medicine. If a person dies because (s)he was treated, for example, homeopathically, it makes headlines in the press. But at the same time hundreds or thousands die every day in hospitals where they have been treated materialistically. What a double standard and what hypocrisy! Although the person who was treated through homeopathy might have been saved by materialist medicine, some of the people who died while being treated materialistically, might have survived by treatment of alternative medicine. And, indeed there are many successes of alternative treatments, including treatment of some cancers. But these successes are often discounted as anecdotal exceptions by the medical establishment.

Yet taking exceptions seriously is important for an open-minded scientist because the recognition of exceptions has often led to important innovations in science as historians of science are well aware. To ignore or devaluate what does not fit our cherished paradigm, will not help us to advance to a better understanding of reality. But David Lane, who does not subscribe to metaphysical materialism and admits that we may go beyond materialist science, insists “that we won't truly get “beyond” matter until we have fully explored all of its subtleties first” [5]. With this insistence, we will have to wait forever because science, including materialist science, appears open-ended. Thus, demanding full exploration of the materialist approach before we can explore non-materialist aspects of reality appears unrealistic and impossible. It also blocks the way to alternative explorations beyond materialism. Thus, if we have to wait till materialist science will have been fully explored, we shall wait in vain till we die and we will have deprived ourselves of scientific explorations and insights beyond materialism.

Simplicity and Complexity Theories

Another reason that is given in defense of materialist science is “Ockham's Razor.” Frank Visser wrote:

“science should always follow the economy principle (“Ockham's Razor”) which holds that we should first look for the most simple explanation, before introducing more complex principles. Materialism therefore is the first candidate that comes into view” [4].

However, in view of the utter complexity of manifest reality, I would not say “always.” We are at a stage of scientific understanding where complexity theories play a very important role. They seem predominantly materialistic, but they may also go beyond materialism. We are well aware of the influence of the mind (that so far has not been reduced to matter). Think, for example, of the placebo effect. And simplicity (“Ockham's Razor”) seems relative. To a materialist disregarding the mind and just focusing on material objects appears simple, but to a non-materialist simplicity may be seen differently (if he or she is indeed possessed by Ockham's Razor). Thus, in other cultures, accepting a vital force such as chi or prana that pervades the universe, including ourselves, may appear simple and straightforward. Emphasizing and focussing on the material seems a predilection of Western culture and has historical reasons because science in the Renaissance began with the great successes in physics and astronomy, and then the materialist approach was transferred to other areas of research such as the life sciences.

Some Personal and General Comments

I might also add that the indoctrination with materialist science is very strong.

I have learned much about the strength and power of materialist science as well as its weaknesses and limitations because I have worked in academia for 35 years and most of my research and publications in plant biology have been materialist. Only after obtaining tenure could I dare to look a little beyond materialism. So I know from personal experience in the biology department at my university and universities all over the world that I have visited that the materialist approach, a “physics-first approach” [5], has been dogmatically enforced, which has become stifling and “suicidal” for almost any researcher who wants to go beyond it.

By “suicidal” I mean that it would be most unlikely that a researcher who dares to look beyond materialist science could get or retain a position in a biology department and probably other science departments of a university or research institute. Such “luxury” might be possible for rare individuals only after they have obtained tenure and even then the pressure to conform is enormous. Furthermore, it would be very difficult to publish non-materialist scientific research in so-called reputable journals such as Nature or Science that are usually controlled by materialist scientists (editors and reviewers). I am grateful to Frank Visser that (as far as I know) he publishes our contributions to Integral World uncensored.

I might also add that the indoctrination with materialist science is very strong. Students usually are offered no alternatives. I know this indoctrination from personal experience. Because it seems rather subtle, it took me a long time to become aware of it and to then get over it. Subsequently, for many years I taught courses in the history and philosophy of biology. When I retired these courses were cancelled because they were considered unimportant. Maybe they could be taught in philosophy and history departments. In science departments we don't have to waste our time with history and philosophy - so I was told - because the researchers think they know that living organisms are material objects – that is the prevailing mentality. Obviously it is very difficult to go beyond materialist science in such an intellectual climate. It seems there are only rare pockets of openness here and there. But who knows, maybe some time in the future something extraordinary will emerge from these pockets.

In this context, a final comment on David Lane's philosophy of focus and practicality [5]. Although focus has great merits, it can become too limiting and give us a distorted view of reality. If I just focus on one leaf of a tree and don't see the other leaves, I get a distorted view of what is there. Similarly, if I just focus on the material, I get a distorted view of reality. Furthermore, assuming that the material approach is more practical than others may also be distorting and may have negative consequences because of the unnecessary limitations. I agree that it may appear more practical for someone who has been conditioned by materialism and therefore is biased in this direction. But in my life, it has often been more practical to transcend the materialist bias. For example, for me it has been more practical and more beneficial to get treatment from an acupuncturist than from a conventional materialist doctor. And I know many people who have made similar experiences. But I am not against conventional materialist medicine. It too can be very helpful in many cases. Therefore, as I pointed out above, materialist medicine and alternative medicine complement one another. Both appear practical.

Although David Lane emphasizes so much focus on materialist science and its practicality, he refers to Donald Hoffman's interface theory of conscious realism [5]. According to this theory, consciousness is fundamental, can be described mathematically, but cannot be derived from matter (i.e., the brain), which means that physicalism is wrong: space, time, and physical objects do not exist independently of any observer; they are constructs of consciousness and may be compared to icons on a computer screen, which are just symbols for a complex underlying reality [14]. In addition to Hoffman's theory, David Lane also refers to unknowingness. He wrote: “I feel a kinship with Socrates, Lao Tzu, and Nicholas of Cusa, who each professed to a radical unknowingness and how this in turn led them to a free and open inquiry of reality” [5]. That's what we need: free and open inquiry of reality.

Conclusions

We can go beyond materialist science and still remain scientific in one sense or another since science has been and can be defined in many different ways [6]. Materialist science is only one way among all the other ways.

Often, we make a distinction between body and mind, or body, mind, and spirit, or three bodies or energies: the gross, subtle, and very subtle (causal) body or energy. Materialist science admits and investigates only the gross body and disregards the other bodies or energies. But there is subjective and objective evidence for the other bodies or energies [15]. Ignoring or neglecting them leads to an impoverished science and an impoverished society and lives. Instead of distinguishing only three bodies or energies, finer distinctions have also been made. For example, Greene [16] distinguishes four bodies or energies in addition to the physical body. Since they are coupled with information, she refers to inergy. Ultimately, all distinctions may have to be superseded. Thus, Greene notes that the bodies or energies (inergies) form a continuum, and this continuum also represents a continuum of consciousness from selective to universal consciousness.

How science can deal with this continuum remains a challenge. Materialist science cannot do it because it deals only with matter, the gross body and its energy. But even a more comprehensive science has limitations for various reasons [6]. All science, as it uses language or mathematics, fails to grasp reality as it is as Korzybski has so well demonstrated through his Structural Differential:

‘Whatever one might say something‘ is ‘it is not.’ Whatever we might say belongs to the verbal level and not to the unspeakable, objective levels. [17]

Finally, is “spiritual science” a contradiction in terms as Frank Visser [2] concluded? It depends on what is meant by “spiritual” or “spirit.” If “spirit” refers to the ultimate mystery of reality that, as Korzybski and others have demonstrated, cannot be understood through language, then spiritual science seems indeed a contradiction in terms because science uses language and mathematics (a form of language). If, however, spiritual science implies a conceptual representation of spirit, then there need not be a contradiction; then spiritual science can be understood as the exploration of aspects of fundamental consciousness and their relation to the world as it can be experienced and observed.

Notes

[1] Steve Taylor, Beyond materialism. Why science needs a spiritual perspective to make sense of the world, www.integralworld.net. See also his book Spiritual Science. Why science needs a spiritual perspective to make sense of the world, London, Watkins Media, 2018.

[2] Frank Visser, 'Spiritual Science' is a contradiction in terms – A Response to Steve Taylor, www.integralworld.net

[3] David Lane, Understanding matter – Why a spiritual perspective needs science to make sense of the world, www.integralworld.net

[4] Steve Taylor, Misplaced faith – science, scientism and materialist metaphysics. A response to Lane, www.integralworld.net

[5] David Lane, It's a matter of focus. Confusing practicality with faith, www.integralworld.net

[6] Rolf Sattler, Science: its power and limitations, www.beyondwilber.ca

[7] Rupert Sheldrake, The Science Delusion. Freeing the Spirit of Enquiry. London, Coronet, 2012 (also published as Science Set Free). On p. 207 Sheldrake refers to experiments on rats that were conducted at different universities. These experiments showed that rats that learned to escape from a water maze made it easier for other rats elsewhere to learn the same behaviour.

[8] Eben Alexander, Consciousness and the shifting scientific paradigm, Paradigm Explorer 2018/2: 3-8, explore.scimednet.org.

[9] Rolf Sattler, Wholeness, Fragmentation, and the Unnamable: Holism, Materialism, and Mysticism – A Mandala, www.beyondwilber.ca

[10] James Hoggan with Grania Litwin, I'm Right and You're an Idiot. The toxic state of public discourse and how to clean it up, Gabriola Island, B.C, New Society Publishers, 2016.

[11] Rolf Sattler, Complementarity, www.beyondwilber.ca

[12] Ronald N. Giere, Understanding Scientific Reasoning, New York, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1979.

[13] Paul Feyerabend (ed. by E. Oberheim), The Tyranny of Science, Cambridge, Polity, 2011.

[14] See, for example, Donald Hoffman, Reality is a user interface, www.youtube.com, and Ruben Chavez, Rethinking reality with cognitive scientist Donald Hoffman, inkgrowprosper.com

[15] See, for example, William A. Tiller, Science and Human Transformation. Subtle Energies, Intentionality and Consciousness, Walnut Creek, CA, Pavior, 1997.

[16] Debra Greene, Endless Energy. The Essential Guide to Energy Health. Maui, HI, MetaComm Media. See especially Chapters 1 and 9.

[17] Alfred Korzybski, Science and Sanity, New York, The International Non-Aristotelian Library Publishing Company, 4th edition, 1959, p. 409. For an illustration of the Structural Differential see Steve Stockdale, The Structural Differential and the process of abstraction, www.thisisnotthat.com

|