|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Cross-posted from the RFK Action Front blog, dated June 2009. The blog is inspired by Robert Kennedy: "My goal is to imagine a world where Bobby Kennedy is still alive and to ask the question, What Would Bobby Do? when it comes to the most pressing political issues of our age." Posted with permission of the author.

Understanding evolutionStephen Jay Gould vs. Ken WilberToby RogersGould undercuts not only Wilber's understanding of evolution but the ENTIRE THESIS of Sex, Ecology, Spirituality.

I believe Ken Wilber's Sex, Ecology, Spirituality: The Spirit of Evolution is perhaps the best spiritual treatise ever written. Ever. In human history. Better than the Bible, better than the Torah, better than the Koran, better than the Bagvagita (as frequent readers of this blog will know, I find those other sacred texts rather woeful so perhaps that's not the best comparison). Published in 1995—Sex, Ecology, Spirituality (SES) benefits from the wisdom inherent in modernity but I believe it is also better than any of the modern spiritual treatises (Tolle, Chopra, Chodron) that have been put out over the last few decades as well.

SES represents one of the most ambitious intellectual undertakings ever attempted. Wilber's approach goes something like this: he argues that within any academic discipline (chemistry, sociology, psychology, economics, etc.) there are a generally agreed upon set of facts—and there [are] topics on the edges of the discipline that are still subject to dispute and disagreement. In Sex, Ecology Spirituality, Wilber attempts to take the generally agreed upon facts—from EVERY discipline—and map what we know to be true—from the Big Bang, until today. As I understand it (and this may just be my read, not Wilber's intention) the unspoken hope in creating this map is either to reveal God (if we plot enough data points does it show us the outline of God perhaps—like a sort of constellation of stars?) or point to God (the universe seems to be going in THIS direction so that must point to the Omega point of human existence). Wilber's map, also know as the 4 Quadrants, looks like this:  It won't make sense until you read the book. Regardless of where you come out in terms of his conclusions, I think you'll find that the 4 quadrant map is extremely cool. But (you knew there was a But coming right?) there's something very strange that happens when you talk to people who are into Wilber's "integral theory":

"Our impression that life evolves toward greater complexity is probably only a bias inspired by parochial focus on ourselves." —Stephen Jay Gould

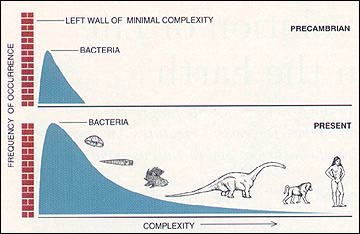

Now some of this may just be professional jealousy. Wilber put this brilliant tome out into the marketplace of ideas and it's natural that some folks would try to knock it a bit—in the hope that some of his greatness might rub off on them through association. I'm sure some of that is going on—but I don't think that's the whole story. I really think SES is a case where the WHOLE is greater than the sum of the parts. Wilber constructs this elaborate house made up of plywood understandings of the various parts that make up the whole. And that's probably fine—the house is beautiful—and it's the most beautiful house on the block. The world needs generalists and the world needs specialists—and they are two different kinds of people.  Stephen Jay Gould (1941-2002) Recently, I started reading Stephen Jay Gould, because I felt like I wanted to better understand evolution, evolutionary biology, and evolutionary psychology. And in a few short sentences, Gould undercuts not only Wilber's understanding of evolution but the ENTIRE THESIS of Sex, Ecology, Spirituality. Gould is not writing in reply to Wilber—he's just writing about the evolution of life on earth, but he comes to every different conclusions than Wilber. I want to chew on a few quotes and then talk about what all of this might mean [you can read Gould's whole piece here] [1]: One might grant that complexification for life as a whole represents a pseudo-trend based on constraint at the left wall but still hold that evolution within particular groups differentially favors complexity when the founding lineage begins far enough from the left wall to permit movement in both directions. Empirical tests of this interesting hypothesis are just beginning (as concern for the subject mounts among paleontologists), and we do not yet have enough cases to advance a generality. But the first two studies—by Daniel W. McShea of the University of Michigan on mammalian vertebrae and by George F. Boyajian of the University of Pennsylvania on ammonite suture lines—show no evolutionary tendencies to favor increased complexity.  PROGRESS DOES NOT RULE (and is not even a primary thrust of ) the evolutionary process. For reasons of chemistry and physics, life arises next to the "left wall" of its simplest conceivable and preservable complexity. This style of life (bacterial) has remained most common and most successful. A few creatures occasionally move to the right, thus extending the right tail in the distribution of complexity. Many always move to the left, but they are absorbed within space already occupied. Note that the bacterial mode has never changed in position, but just grown higher.

Moreover, when we consider that for each mode of life involving greater complexity, there probably exists an equally advantageous style based on greater simplicity of form (as often found in parasites, for example), then preferential evolution toward complexity seems unlikely a priori. Our impression that life evolves toward greater complexity is probably only a bias inspired by parochial focus on ourselves, and consequent overattention to complexifying creatures, while we ignore just as many lineages adapting equally well by becoming simpler in form. The morphologically degenerate parasite, safe within its host, has just as much prospect for evolutionary success as its gorgeously elaborate relative coping with the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune in a tough external world.... Then this: Although interesting and portentous events have occurred since, from the flowering of dinosaurs to the origin of human consciousness, we do not exaggerate greatly in stating that the subsequent history of animal life amounts to little more than variations on anatomical themes established during the Cambrian explosion within five million years. Three billion years of unicellularity, followed by five million years of intense creativity and then capped by more than 500 million years of variation on set anatomical themes can scarcely be read as a predictable, inexorable or continuous trend toward progress or increasing complexity. And then my favorite quote: Sigmund Freud often remarked that great revolutions in the history of science have but one common, and ironic, feature: they knock human arrogance off one pedestal after another of our previous conviction about our own self-importance. In Freud's three examples, Copernicus moved our home from center to periphery, Darwin then relegated us to "descent from an animal world"; and, finally (in one of the least modest statements of intellectual history), Freud himself discovered the unconscious and exploded the myth of a fully rational mind. Wilber's entire thesis rests on complexification—on the idea that the increasing complexity we see in evolution points us towards God. And here Stephen Jay Gould, one of the world's leading experts on evolution, in just a few short sentences says, 'nope, evolution likes simplicity just as much as complexity.' Oftentimes we look at a theory on paper—and it just feels right and so we become passionate about it.

Look, I don't know who's right, Gould or Wilber (and I imagine some integral theorist out there has found a way to harmonize the two)—but it is alarming to say the least to see Gould, one of the world's experts on evolution look at the same data—and come away with the opposite conclusion (from Wilber). I just want to make two notes about this:

I think there's great food for thought in the dissonance between these two writers.

So again, I don't know who's right or wrong on this issue of the evolutionary merits of complexity vs. simplicity—but I think there's great food for thought in the dissonance between these two writers. I think it also suggests that the next great spiritual work won't be the product of any one person. Increasingly, even the world's smartest person is no match for Google and the modern world's capacity for parallel processing. What would SES look like as a collaborative project with each of its pieces written by the experts in each particular field? Would the thesis still hold or would we end up with a very different map of the universe? [Said slightly differently would it be possible to MAP all of the knowledge on Wikipedia—and if so, what would it tell us?] UPDATES#1: I see that that others have plowed this path before I had (which of course, I should have figured out BEFORE I start writing this post). But if you google: Stephen Jay Gould and Ken Wilber, you'll find lots of interesting further reading. #2: I actually find Stephen Jay Gould's writings on "non-overlapping magisteria" to be unhelpful. So I think Wilber is right to whack him on that.[2] NOTES[1] Stephen Jay Gould, The Evolution of Life on Earth, Scientific American, October 1994. Text available at: http://brembs.net/gould.html [2] See: Ken Wilber, Introduction to Volume 8 of The Collected Works of Ken Wilber (The Marriage of Sense and Soul / One Taste, Shambhala, 2000, p. 2), paragraph: The Relation of Science and Religion. Text available at: wilber.shambhala.com (Note added by Frank Visser).

|