|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

THE NATURAL THEOLOGY

OF

BEAUTY, TRUTH,

AND GOODNESS

STEVE MCINTOSH

To the Readers of IntegralWorld.net:

I have enjoyed this website for many years, and it has been most interesting to follow its evolution. And I can fully understand the frustration that many have expressed about the shortcomings of some of the integral movement's leaders. Criticisms are certainly appropriate in many cases, and in my new book I do advance a number of critiques of Ken Wilber's work. But even though I am not directly associated with the Integral Institute, I do continue to identify myself as Wilber's alley and supporter. And this is because, like most of you, I believe that the integral worldview represents our civilization's best hope for progress. Thus I contend that as integralists it is our cultural duty to try to build cohesion within the integral movement and to exhibit a sense of ownership and commitment to this emerging new worldview. This integral perspective is bigger than any one person's philosophy, and so I hope that the opinions and scholarship on this website will continue to evolve in a way that demonstrates this truth.

Frank Visser was kind enough to invite me to contribute something from my book. But rather than simply providing an excerpt, I want to share my latest work, which takes the form of an integral spirituality lecture I'll be giving to a variety of audiences in the next few months. Much of this material can be found in my book, but this 60 minute lecture script (which is designed to be accompanied by an illustrative power-point presentation) represents a revised and updated summary of some of the new thinking that I'm attempting to bring to the field. I also offer this piece on integral spirituality to try to counterbalance the focus on “integral politics” that has resulted from the recent interview of me in What Is Enlightenment? Magazine.

So thanks for considering my plea for solidarity among integralists; this is a pivotal moment in human history, and by working together and continuing to focus on the positive potentials of this emerging new worldview, we can make a real difference.

Steve McIntosh,

October, 2007

INTRODUCTION

This is a presentation about how the values known as the beautiful, the true, and the good play a central role in the evolution of the universe. We'll be considering this ancient and venerable triad of values from the perspective of integral philosophy to see how beauty, truth, and goodness actually serve as attractors of evolutionary development that pull evolution forward “from the inside” through their influence on consciousness.

In this presentation, we will be examining what is coming to be known as the “Cosmogenetic Principle.” The Cosmogenetic Principle is a description of the overall character and shape of the process of evolutionary development that can be recognized in each domain of evolution's unfolding. In other words, as we come to recognize evolution in nature, self, and culture, we can begin to detect certain overarching principles that tie these diverse domains of evolution together and show the larger contours and currents of evolution as a whole.

As we will explore, there is a master systemic pattern that configures all forms of evolutionary development, and as we come to better see and understand this pattern, it can help us in our efforts to improve the human condition by acting as agents of evolution. And as I hope to show, the values of beauty, truth, and goodness are an essential aspect of this Cosmogentic Principle, and an important key to what might be called “the physics of the internal universe.”

I've used the term “natural theology” in the title of this talk in order to emphasize how values in general, and these primary values in particular, demonstrate the reality of spirit in an unmistakable way. However, the natural theology of beauty, truth, and goodness is not to be confused with other, earlier forms of natural theology, such as arguments from design. From my perspective, integral natural theology is found in the direct experience of spirit that is common to every spiritual path; it does not rely on the authority of spiritual teachers or texts. Integral natural theology seeks to discover the movement of spirit in the world within the immediacy of our own experience. That is, within the exquisite pleasure of beauty, within the exciting wonder of truth, and within the warm glow of loving-kindness, which accompanies all experiences of authentic forms of goodness.

The thesis of this presentation is that the primary values of beauty, truth, and goodness can be expansively understood as the actual directions of evolution. And understanding where evolution is headed is, of course, a central inquiry for a philosophy that defines itself in evolutionary terms. But questions about of the directions of evolution's unfolding are not just relevant to integral philosophers; properly understood, these questions relate to every situation in which the need for improvement can be recognized. And as it now becomes increasingly necessary for humanity to participate in guiding cultural evolution toward a more positive future, knowledge of evolution's essential methods, techniques, and directions is of critical importance.

VALUES AND EVOLUTION

Although cosmological and biological evolution may be apparently driven by mechanistic processes, cultural evolution is clearly driven by humanity's quest to improve its conditions. And this quest for improvement is itself driven by that which people consider to be valuable.

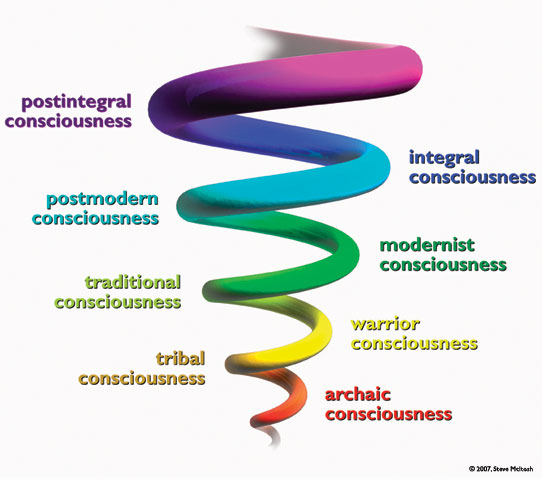

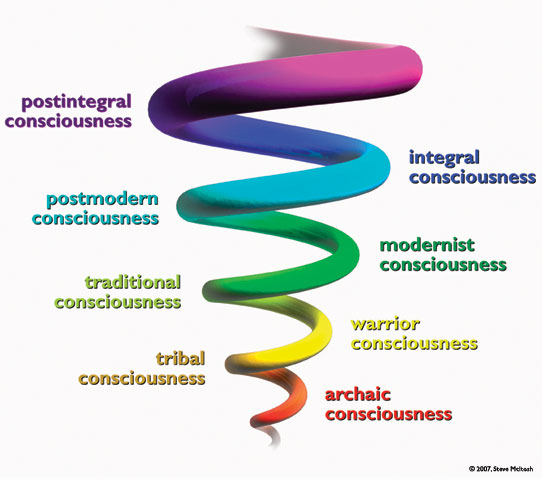

This is especially evident when we consider the importance of values from the perspective of the spiral of development. Integral philosophy's understanding of the spiral shows us how each stage of consciousness constructs its worldview out of agreements about values. These value agreements generally arise out of the struggle to find solutions to the problematic life conditions faced by those who participate in a given worldview. Each stage of culture thus develops a discrete set of values that are tailored to its location along the time-line of human history. This is one reason why values are “location specific” — as life conditions change with the progress of cultural evolution, that which is most valuable for producing further evolution likewise changes.

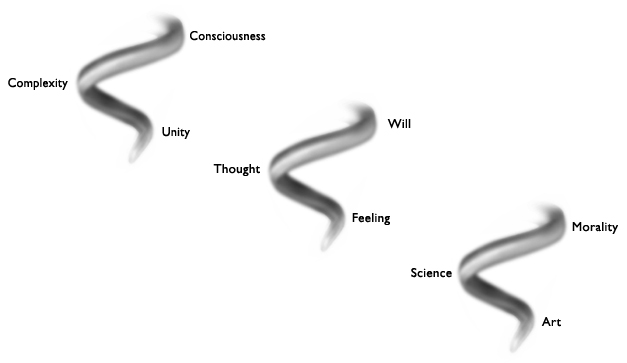

The spiral of development in consciousness and culture

The spiral of development in consciousness and culture

So each stage of the spiral can be understood as an “octave of values”, or a discreet bandwidth of values that exists within a larger evolutionary spectrum. Each of these worldview structures maintain their organizational integrity by using values as the energy-like source of their systemic metabolism in a manner similar to the way the external systems of evolution use physical energy. And when we begin to see how values share certain properties with energy, we then begin to recognize how values are naturally organized in a holarchy. And at the apex of this holarchy are the primary values of beauty, truth, and goodness.

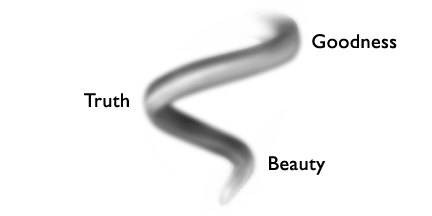

BEAUTY, TRUTH, AND GOODNESS — THE PRIMARY VALUES

The beautiful, the true, and the good — these are the fundamental values that have been recognized since antiquity as the intrinsic qualities from which all values are essentially derived. Just as a million shades of color can be mixed from three primaries, so too can a million shades of quality be traced back to these primary values.

The first writer to associate the beautiful, the true, and the good together, and to exalt these three as primary was the famous Greek philosopher Plato. And since Plato in the 4th century B.C., this triad of terms has continued to impress itself upon the minds of thinkers down through the centuries. This is not to say that all the proponents of beauty, truth, and goodness have been followers of Plato; some have discovered the significance of this triad through decidedly non-philosophical methods. But whether they are arrived at through intuitive inspiration or rational deduction, these three terms keep showing up in the writing of a wide variety of notable luminaries, including thinkers as diverse as Immanuel Kant, Sigmund Freud, Albert Einstein and Mohandas Gandhi. Even the Encyclopedia Britannica acknowledges the significance of this ubiquitous trio, stating that:

Truth, goodness, and beauty form a triad of terms which have been discussed together throughout the tradition of Western thought. They have been called “transcendental” on the ground that everything which is, is in some measure or manner subject to denomination as true or false, good or evil, beautiful, or ugly.

In addition to philosophers, scientists, and politicians, many mystics and spiritual teachers have also championed the idea of these three essential “windows on the divine.” This list includes Rudolph Steiner, Sri Aurobindo, Thich Nhat Hanh, and even Osho Rajneesh. For example, Sri Aurobindo describes what he calls “three dynamic images” through which one makes contact with “supreme Reality.” These are:

- The way of the intellect, or of knowledge — the way of truth;

- The way of the heart, or of emotion — the way of beauty; and

- The way of the will, or of action — the way of goodness.

Aurobindo comments further that “these three ways, combined and followed concurrently, have a most powerful effect.” [1]

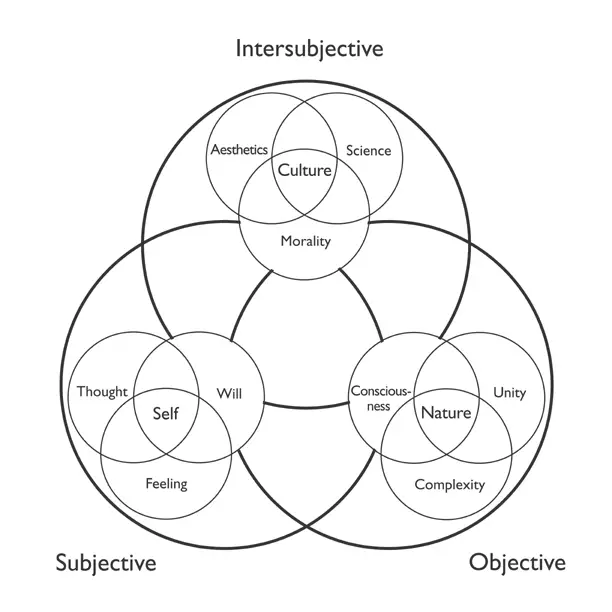

The triad of beauty, truth, and goodness has also garnered considerable attention from the founders of integral philosophy itself. Alfred North Whitehead devotes a significant portion of his book Adventures of Ideas to the discussion of the primary values, which he calls the “eternal forms.” Likewise does Ken Wilber acknowledge the priority of the beautiful, the true, and the good by connecting them with the three main “cultural value spheres” of art, science, and morals, which he further equates with the subjective, objective, and intersubjective domains of evolution, respectively.

Now, of course, the idea of any kind of “primary values” drives deconstructionist postmodern academics crazy. For them, values are arbitrary interpretations imposed by establishment power structures, so the proposition that there are three fundamental values is the height of idealistic pretense. After all, beauty, truth, and goodness are just conceptual categories, just abstract words that point to nebulous ideals that perhaps everyone can agree about, that is, until you actually get specific. There is certainly no “hard proof” that all human values can be captured and expansively described using these three concepts. But there is a remarkable degree of “consensus evidence” about the special significance of beauty, truth, and goodness.

So you may ask, why is this? Why not exalt “wisdom, compassion, and humility,” or any other group of lofty ideals? Well, I think the reason that beauty, truth, and goodness have received continuous veneration is because they correspond to some very deep intuitions about the way the universe works. As I'm about to argue, the primary values are essential descriptions of the primordial influences at the heart of all evolutionary development. And if this is true, then there are some very good reasons for the remarkable agreement about this specific triad of values.

There have certainly been many attempts by philosophers to provide concise definitions of these concepts. Thomas Aquinas defined beauty as: “unity, proportion, and clarity.” Whitehead defined truth as: “the conformation of appearance to reality.” And Kant defined goodness by reference to the “categorical imperative,” which says: “Act according to those maxims that you could will to be universal law.” However, like spirit itself, the values of beauty, truth, and goodness cannot be easily defined in abstract terms apart from the situations in which we experience them. And compounding this definitional difficulty is the fact that these values are evolving and changing along the dialectical trajectory of the spiral of development wherein each new octave of values arises in partial antithesis relative to the values that came before.

However, even though exactly what is beautiful, true, or good, is defined specifically (and often conflictingly) by each successive stage of development, the overall valuation of the general directions of the beautiful, the true, and the good remains a common feature of each level. In other words, the values of beauty, truth, and goodness act as compass headings for the improvement of the human condition, regardless of the assessor's psychic location. Even though each stage of development has its own version of what is valuable, we can see how the spiral as a whole does act to define the overall trajectory of evolving values for both the individual and the culture. So regardless of the “internal location” of a person's consciousness, we can identify something that is beautiful, something that is true, and something that is good from their perspective. Within the consciousness of every level, the general directions of evolution tend toward more pleasurable feelings, truer thoughts, and decisions that consider the welfare of larger and larger communities.

According to Plato and Whitehead, we can observe within the universe a certain “Eros,” which has been defined as “the urge towards the realization of ideal perfection.” And in our consciousness, this Eros of evolution — this hunger for greater perfection — is stimulated by the eternal images of the beautiful, the true, and the good, which spur us onward and upward and inward into increasingly more evolved states.

But in order for beauty, truth, and goodness to have this consciousness raising effect, these values have to be practiced and lived out. Indeed, the practice of the primary values actually serves to energize our consciousness by providing input and throughput for its systemic metabolism. Like electricity, values are not static or absolute, values are “alive, free, thrilling, and always moving.” And recognizing the energy-like quality of values shows us how their practice is best approached as a kind of circuit by which their experience is taken in and given out.

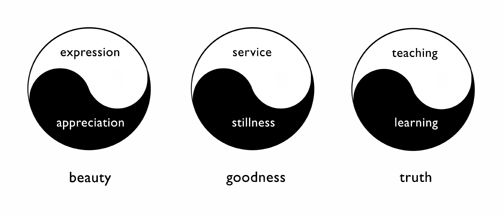

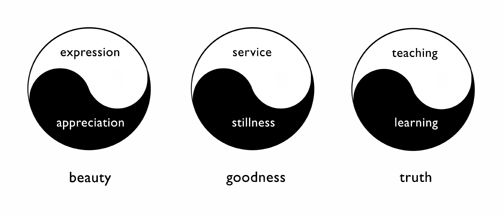

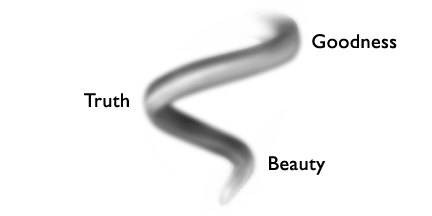

The giving and receiving practices that enact

The giving and receiving practices that enact

the primary values' circuits of experience.

We metabolize truth by the practice of learning and teaching, we metabolize beauty through appreciation and expression, and we can fully experience the spiritual nutrition of goodness through the practices of service and stillness.

The practice of truth involves the discernment of that which is most real in what we experience. Truth is like a light that illuminates the potential for progress, giving us the power to see how things really are, and thereby to improve any situation by making contact with actual conditions. The practice of beauty involves feeling the pleasure and delicious satisfaction that results when our emotions become entrained to the vibrations of universal unity found in nature and in certain forms of human art. Beauty provides a fleeting glimpse of relative actual perfection. According to Whitehead, “beauty is the final contentment of the Eros of the universe.”

And like the practices of truth and beauty, the practice of goodness can also be understood through the giving and receiving rhythm of service nurtured by stillness. Service is a way of communicating goodness to another person. But service doesn't have to be about volunteering at the soup kitchen; the spiritual practice of service also includes all the ways that we can teach truth and express beauty. And we can receive goodness directly from its source through the spiritual experiences provided by contemplation, meditation, prayer, and worship; practices which might be collectively characterized as forms of stillness.

In my experience, the ideals of beauty, truth, and goodness represent philosophy's finest hour — these are the concepts by which philosophy makes contact with the spiritual and helps to define the way forward from a middle ground in between science and religion. The concept of the primary values of beauty, truth, and goodness is a conceptual cathedral. And these concepts do produce spiritual experience in the way that they name and describe the “eternal forms” by which the “gentle persuasion” of evolution enacts the universe's essential motion of consciousness seeking its source.

So it is from this perspective that we can perhaps begin to see how these primary values, these glimmers of relative and fleeting perfection, are truly the comprehensible elements of Deity — some of the most direct ways that we can experience the movement of spirit in the world.

OK, so with this background in mind, we'll now explore how these distinct aspects of perfection, these attractors of evolutionary development, actually shape the character of evolution in its “three big” domains of nature, self, and culture.

EVOLUTION AND THE IDEA OF PROGRESS

So first I have to ask you: has evolution made any progress in the last 13.7 billion years? Have things gotten any better since the Big Bang? Has there been progress in matter from the isolated atoms of hydrogen gas to the blue jewel of planet earth? Has there been progress in life from single-celled prokaryotes to self-conscious human beings? Has there been progress in culture from archaic human survival bands to the 21st century's global civilization?

To my mind these are, of course, absurd questions. But amazingly enough, today most scientists vehemently deny that evolution is moving forward. The idea that evolution represents progressive development is dismissed as a quaint Victorian notion that has now been thoroughly disproved by the neo-Darwinian synthesis, which has shown how undirected forces, blind and unintelligent, are the sole causes of the order we see in the universe. Advocates of scientism generally eschew the idea of “higher” or “lower” forms of evolution, claiming that such ranking involves a value judgment that has no part in the scientific discourse. Yet even as they maintain that science cannot make value judgments about higher and lower, scientific luminaries such as Stephen Jay Gould are perfectly willing to claim the status of “science” for their value judgment that there is no value in evolution.

However, there are a few outspoken scientists who are willing to admit that “advancing complexity” as an unmistakable form of material progress in evolution. Here's a quote from well-known scientific materialist E. O. Wilson, who states this case as follows:

It is, I must acknowledge, unfashionable in academic circles nowadays to speak of evolutionary progress. All the more reason to do so. In fact, the dilemma that has consumed so much ink can be evaporated with a simple semantic distinction. If we mean by progress the advance toward a preset goal, such as that composed by intention in the human mind, then evolution by natural selection, which has no preset goals, is not progress. But if we mean the production through time of increasingly complex and controlling organisms and societies, in at least some lines of descent, with regression always a possibility, then evolutionary progress is an obvious reality. [2]

Yet even this grudging admission of the progress of increasing complexity reveals the narrow orthodoxy of the modernist fundamentalists who pose as the high priests of our society's truth. As a result of scientism's quasi-religious commitment to the metaphysical principles of materialism, we can see how anything in the natural world that points to a spiritual influence, such as progress in evolution, is downplayed, belittled, attacked, and dismissed.

However, scientists who have achieved a more postmodern center of gravity are less influenced by these materialistic biases, and are thus generally more willing to recognize the marvelously progressive nature of evolutionary development. One such scientist is Ervin Lazslo, who writes:

In evolution there is a progression from multiplicity and chaos to oneness and order. There is also progressive development of complex multiple-component individuals, fewer in number but more accomplished in behavior than the previous entities. Evolution does go one way rather than another, and keeps on going that way as long as it does not come into conflict with basic physical laws. … We cannot see how evolution could fail to push toward organization and integration, complexity and individuation, whatever forms it may choose for realization. [3]

This quote by Laszlo brings out another aspect of evolutionary progress that cannot be adequately described as increasing complexity, and this is countervailing force of increasing integration or unification. As evolution advances and organisms become more complex, this accumulating complexity results in an increasing interdependence among the system's components. In other words, for a system or structure to maintain its integrity as it becomes more complex, it must become more unified — each part of the system must work together with a large number of other parts, and together with the system as a whole.

For example, a squirrel is a more unified system than a starfish. We can cut off the leg of a starfish, and not only will the starfish grow a new leg, but the old leg will grow a new starfish. However, if a squirrel is deprived of one of its legs it will not fair as well. And this is because mammals, being more complex systems than mollusks, require greater degrees of systemic unity for their existence. The parts of the system are more interdependent — each part is absolutely necessary for the proper functioning of the system as a whole.

But it is, perhaps, predictable that scientists have tried to characterize the advance of evolution as simply an increase in complexity because their primary tool is analysis. Science goes about understanding the complex world by breaking it down into its parts, by analyzing a system through its components. Science is good at recognizing and analyzing complexity, so it naturally sees complexity as “the fundamental principle of the development of pattern.” But science is not as good at recognizing unity as it is at recognizing complexity. And this is because recognizing unity is primarily the job of art, and not the job of science.

As another example of increasing unity in evolution, consider the artful unity of the higher mammals. What makes the higher mammals more evolved is not just their greater complexity, but also the way they exhibit greater unification. Cats, for instance, are not just more complex than frogs, they are also more graceful, more refined, more elegant, and more beautiful. And these expressions of feline beauty arise more from the singularity or unity of what it is to be a cat than from any attributes of a cat's evolutionary complexity — the grace is not in the parts, it is in the coordinated functioning of the whole. So we can see that as material evolution advances, its forms exhibit not only greater complexity but also greater unity — not just more “partness” but also more wholeness.

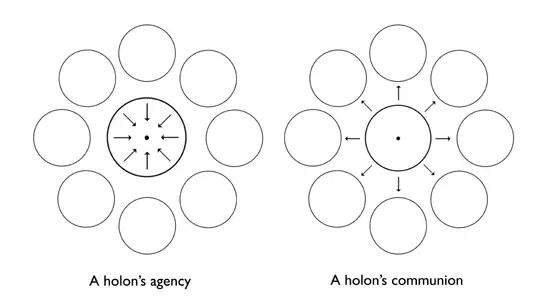

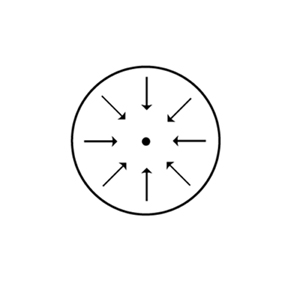

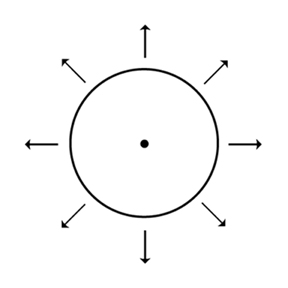

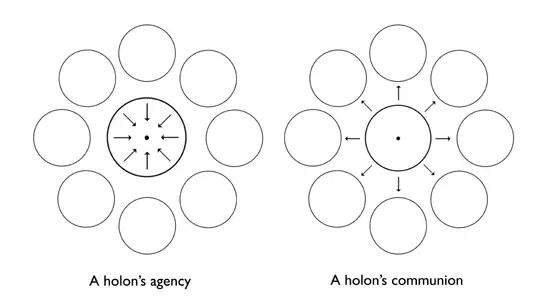

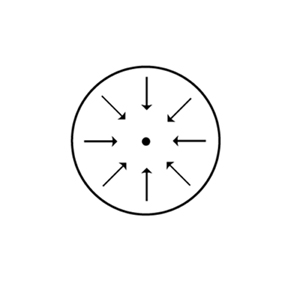

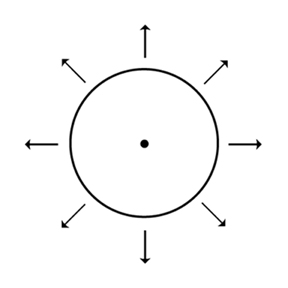

The way evolution functions through the interpenetrating forces of unity and complexity becomes particularly evident within the understanding of evolutionary development provided by the theory of whole/part systems or holons. The theory of holons states that every evolutionary system exhibits what Ken Wilber calls “agency and communion.” As illustrated below, each whole/part holon is an autonomous whole in itself — this is its agency, its drive toward self-unity or wholeness; yet every system is also a part of a larger system — this is its communion, its drive to participate in a greater complexity beyond itself.

Holonic agency and communion

Holonic agency and communion

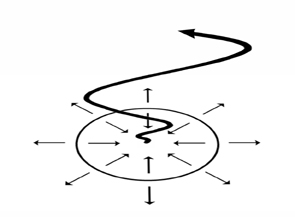

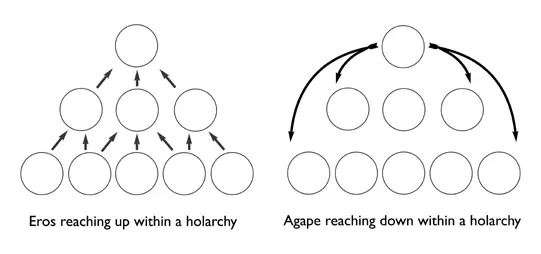

According to holonic theory, not only can we see these drives toward unification and complexification within each individual holon, we can also see the manifestation of these forces within multi-level hierarchies of holons known as holarchies. And within every holarchical system can be found the twin drives which Wilber calls “Eros and Agape.” As illustrated in this next diagram, Eros is the tendency of every systemic level to “reach up from the lower to the higher,” and Agape describes the tendency of higher-level holons to “reach down from the higher to the lower.”

Holarchic Eros and Agape

Holarchic Eros and Agape

These twin drives of holons and holarchies reveal the way that evolution advances through the combined processes of differentiation and integration, complexification and unification, or put simply: transcendence and inclusion. That is, complexity or differentiation is the direction of transcendence, and unity or integration is the direction of inclusion. Even though these processes can be intermittent and nonlinear, and even though they are always subject to pathology or regression, they have nevertheless managed to produce our bodies, our minds, and this marvelous world we call home.

However, in our consideration of evolutionary development in the natural world, there is still a crucial factor that is missing from our analysis. In addition to the interpenetration of differentiation and integration, there is another “obvious reality” that is rarely mentioned or acknowledged by scientists as a progressive product of evolution, and this is consciousness itself.

Can there be any doubt that one of the most obvious and astounding products of evolutionary development is the emergence of sentient subjectivity? Indeed, from the perspective of integral philosophy the fact that evolution has produced a sequential series of organisms that exhibit increasing degrees of awareness is the whole point of evolution. Whitehead actually defined evolution as “an increase in the capacity to experience what is intrinsically valuable.” Teilhard de Chardin similarly recognized the inseparability of the growth of complexity and the growth of consciousness in his famous “law of complexity-consciousness,” which maintains that these two terms are simply the inside and the outside of the same essential pattern of growth.

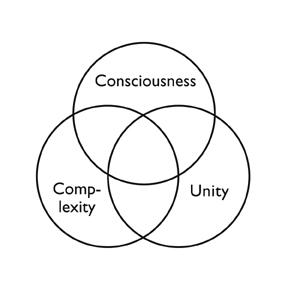

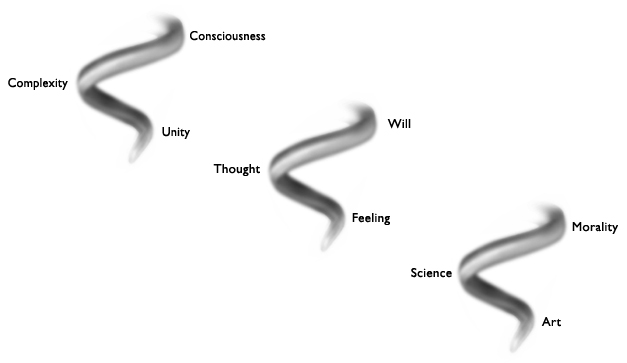

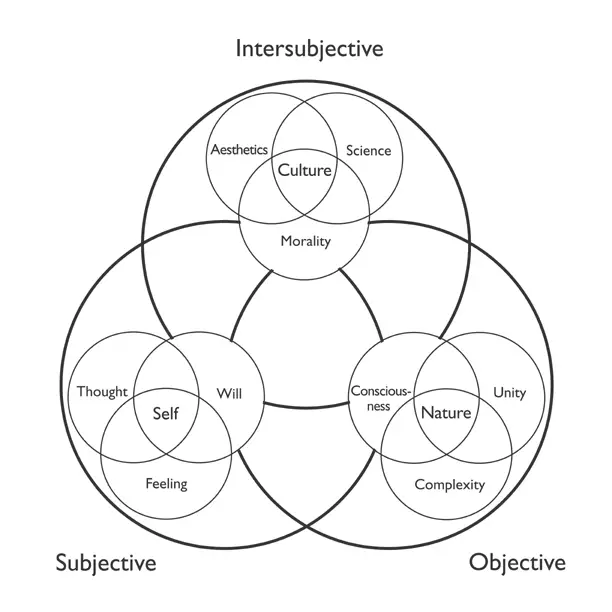

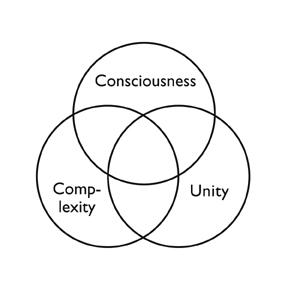

So when we include the growth of mind within our assessment of evolutionary development, we can actually see three major trends or products of evolution's advance in the natural world — increasing unity, complexity, and consciousness. As illustrated in this Venn diagram, without violating any scientific principles, and without resorting to any kind of metaphysics, we can see that material evolution (in at least some lines of development) has produced systems that exhibit increasing integration, differentiation, and sentient subjectivity.

Products of natural evolution

Products of natural evolution

This simple diagram reveals a larger threefold pattern of evolution that can be observed not only within the external, natural realms of evolution, but also in the internal realms of consciousness and culture. So as you look at this pattern, notice that increasing complexification and unification are clearly observable physical trends, but consciousness, although observable, is not physical. Although science does not generally account for consciousness in its estimates of evolutionary progress, few scientists deny that it exists or that it is indeed a product of material evolution. Biologists generally ignore consciousness because it is in the body, but it is not entirely of the body — consciousness transcends the objective systems of biology through its extension into the subjective domain of evolution. So for now, I want you to simply note this pattern of two opposing forces interacting to produce a transcendence to a new level — we'll be returning to this pattern in a few moments.

And I want to quickly add that the recognition of this threefold pattern of evolution is not some novel idea of mine, this is a pattern that has been previously described by one of the most distinguished thinkers in the field, the cosmologist Brian Swimme. In the influential book, The Universe Story, Swimme and historian Thomas Berry weave together the latest science into a coherent narrative of the long sequence of transformations, beginning with the Big Bang, that have led to the development of the universe, planet earth, and human consciousness. And through their careful evaluation of the scientific evidence these authors identify what they in fact call the “Cosmogenetic Principle” that is behind all forms of evolutionary development. According to Swimme and Berry:

The Cosmogenetic Principle states that the evolution of the universe will be characterized by differentiation, autopoiesis and communion throughout time and space and at every level of reality. These three terms — differentiation, autopoiesis and communion — refer to the governing themes and the basal intentionality of all existence. … These three features are not “logical” or “axiomatic” in that they are not deductions within some larger theoretical framework. They come from a post hoc evaluation of cosmic evolution; … The sequence of events in the universe becomes a story precisely because these events are themselves shaped by these central ordering tendencies — complexity, autopoiesis and communion. These are the cosmological orderings of the creative display of energy everywhere and at any time throughout the history of the universe. [4]

Let's pause and reflect on the significance of this quote. As Swimme and Berry recognize, these “governing themes” of evolution, which I am calling unity, complexity, and consciousness, and which they call communion, differentiation, and autopoiesis or sentient subjectivity, represent a very important teaching about the nature of the universe. Although these authors' understanding of what they call the “central ordering tendencies” of evolution is not informed by the clarifying perspective of integral consciousness, I think they have nevertheless come very close to describing the threefold character of evolution's overall master pattern.

Although The Universe Story may not be a definitive scientific text, it is certainly more than mere New Age speculation — the authors attest that the threefold nature of evolution's “basal intentionality” has been discovered through a “post hoc evaluation” of the facts of science. However, we don't have to take their word for it; I trust our discussion so far has also shown how evolution develops through increasing differentiation and integration, how the results of the outworking of these two forces is increasing consciousness, and how this is perfectly evident to anyone willing to consider the patterns of evolutionary development. Swimme and Berry's discernment of a Cosmogenetic Principle is thus an idea I want to adopt, modify, and explore further, because I believe we can see this principle at work not only in the external universe of chemistry and biology, but also in the internal universe of consciousness and culture.

DIRECTIONS OF EVOLUTION IN THE INTERNAL UNIVERSE

In this investigation of the directions of evolution, my goal is to advance integral philosophy in a manner that carefully builds upon science, but that also includes the internal universe of consciousness and culture within the purview of its investigation. So now that we've seen how the products of material evolution, when considered together as a whole, suggest principles which, according to Swimme and Berry, are the “cosmological orderings of the creative display of energy everywhere and at any time throughout the history of the universe,” we are ready to see whether this Cosmogenetic Principle holds true in the internal universe as well as the external.

We'll start with consciousness by examining one of the most influential books of the 1990s entitled: Emotional Intelligence, written by psychologist and New York Times reporter Daniel Goleman. In this book Goleman marshals considerable scientific evidence that shows how “the folk distinction between 'heart' and 'head,'” actually approximates real neurological and psychological structures. According to Goleman:

In a very real sense we have two minds, one that thinks and one that feels. These two fundamentally different ways of knowing interact to construct our mental life. One, the rational mind, is the mode of comprehension we are typically conscious of: more prominent in awareness, thoughtful, able to ponder and reflect. But along side that there is another system of knowing: impulsive and powerful, if sometimes illogical—the emotional mind. … These two minds, the emotional and the rational, operate in tight harmony for the most part, intertwining their very different ways of knowing to guide us through the world. Ordinarily there is balance between emotional and rational minds, with emotion feeding into and informing the operations of the rational mind, and the rational mind refining and sometimes vetoing the inputs of the emotions. Still the emotional and rational minds are semi-independent faculties, each reflecting the operation of distinct but interconnected circuitry in the brain. [5]

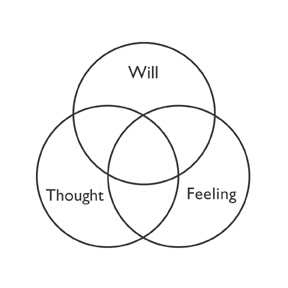

As this quote makes clear, there is significant scientific evidence that cognition and emotion, or simply thoughts and feelings, are “metastructures” that organize distinct areas of the psyche, and that these two kinds of consciousness do operate by “intertwining their very different ways of knowing to guide us through the world.” However, as we consider these two ways of knowing, we can detect that there is still something missing. And what's missing is the faculty of choice and evaluation, the consciousness of intention, the “sphere of knowing” known as human volition or free will.

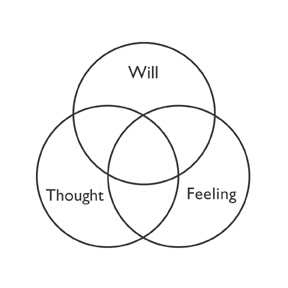

Lines of development within consciousness

Lines of development within consciousness

Indeed, Goleman acknowledges in Emotional Intelligence that free will is in fact an aspect of consciousness that is on par with feeling and thinking. However, Goleman and other leading authors in this area tend to shy away from the subject of free will because it is not really accessible to scientific investigation. Unlike the structures of feeling or thinking, will has not yet been located as a definite structure in the brain. And this is because the uncaused causation of free will is, of course, a thoroughly metaphysical reality. So as with all metaphysical realities, materialist philosophers simply deny that it exists. In fact, advocates of scientism have gone to great lengths to try to show how the idea of freedom of choice is merely an illusion. These thinkers maintain that preexisting physical, biological, and cultural forces ultimately predetermine all human choices. However, while every human choice is certainly influenced by outside factors, whether we believe in free will or not, we all inevitably presuppose in practice that we have freedom of choice, we really can't act otherwise. And this is a marker of the essential truth that humans indeed have relatively free will.

So here again we see this familiar threefold pattern. And in my book I spend an entire chapter discussing the abundant evidence, both structural and phenomenological, that this threefold structure of feeling, thought, and will is a central organizing pattern in human consciousness. But just as the recognition of unity, complexity, and consciousness in external evolution doesn't begin with me, the recognition of feeling, thought and will in the internal universe has likewise been previously recognized by others. Indeed, this pattern was recognized over a hundred years ago by James Mark Baldwin, the founder of developmental psychology. Baldwin was explicit in his recognition that the “three great modes of mental function are intellect, will, and feeling.”

So with this in mind, perhaps we can now begin to see the parallels between the development of nature and the development of self. In the external universe we can see how two material forces --differentiation and integration — intertwine to produce structures which generally exhibit increasing degrees of awareness or consciousness. Similarly, within the evolving domain of consciousness itself two types of neurological activity can be seen interacting within subjective awareness, and out of this interaction (or somehow closely related to it) there arises the third and distinct aspect of intentional volition, through which the human mind is directed.

And as we consider the similarities between the objective evolution of biology and the subjective evolution of human consciousness, we can also see that the third element in both cases is of a different order than the other two elements. As we noted, increasing complexification and unification are clearly observable physical trends, but consciousness, although observable, is not physical — consciousness is in the body, but it is not entirely of the body. Likewise, within the evolution of subjective consciousness itself we can identify the scientifically observable features of emotion and cognition, together with a third feature which is not directly accessible to science. Yet like consciousness, free will is undeniable to all but the most ardent materialist fundamentalists. And this is because free will is in the mind but not entirely of the mind — the value choices of free will are shaped not only by the subjective structures of consciousness but also by the intersubjective structures of evolving human culture.

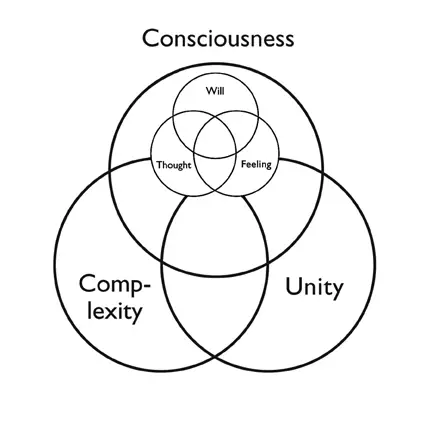

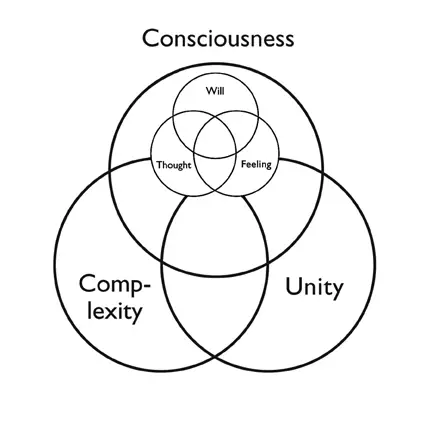

External and internal expressions of the Cosmogenetic Principle

External and internal expressions of the Cosmogenetic Principle

So in light of these arguments it becomes possible to see how there is something very similar behind the basic characteristics of both internal and external evolution. As illustrated in the above diagram, unity and complexity interact in the course of advancing objective evolution to produce biological forms containing minds that are increasingly aware. Then, with the appearance of self-reflective human mind, this threefold pattern of evolution continues within the subjective realm wherein emotion and cognition interact to produce forms of consciousness that contain volitional will that is increasingly free.

These nested diagrams are not intended to suggest that the Cosmogenetic Principle is some kind of deterministic mold, only that these observable patterns do reveal faint traces of the larger currents of a progressive universe.

But as you know by now, this is not the whole story. The evolution of individual organisms or individual minds always proceeds in relationship with a community. As Wilber has shown, not only is the inside connected to the outside, but the individual is also connected to the social and cultural. However, when we extend our investigation of the directions of evolution beyond the realm of objective biology and subjective consciousness to look for these larger patterns of growth within the intersubjective domain of human culture, we must acknowledge that we are leaving science behind and relying exclusively on the arguments of philosophy.

Nevertheless, although the trends of cultural evolution are not as well evidenced as the trends of mental and biological evolution, it is possible to detect the influence of the Cosmogenetic Principle even within the evolution of human culture.

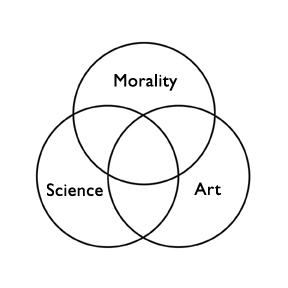

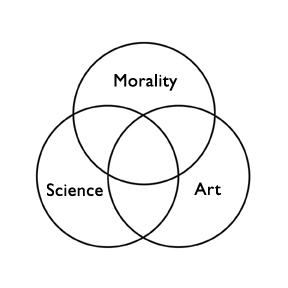

This threefold process of cultural evolution was well recognized by the famous German sociologist Max Weber. Weber dedicated his scholarly life to understanding how the astounding evolution of the culture of modernity was achieved. Writing in the early 20th century, Weber recognized that during the Enlightenment, in the process of rationalization and secularization, different aspects of the once-monolithic religious culture of Europe became separated and differentiated into three distinct “value spheres,” which he identified as art, science, and morality. And so here it is again, this same threefold pattern.

Lines of development within culture

Lines of development within culture

As a result of the differentiation of the value spheres, science, art, and political organizations were liberated from the constraints of the Church and were able to achieve new progress by following their own inner logic. This differentiation allowed science, morality, and art to be judged not according to “religious correctness,” but according to the now better understood categories of “truth,” “justice” and “beauty,” respectively. Weber thus built upon Kant's critical analysis of human thinking in terms of pure reason, practical reason, and aesthetic judgment by showing how the spectacular achievements of modernism were actually brought about by the emergence of separate realms of cultural development, which allowed for the fuller expression of these three essential aspects of human thought.

Weber's philosophy of cultural evolution has influenced a wide variety of writers, and most notably Jürgen Habermas, whose recognition of these three “differentiations of modernity” has featured prominently in his work. Following Weber and Habermas, Wilber has also made use of the concept of these three value spheres in his depiction of the historical evolution of modernist consciousness. Wilber, however, has extended the concept by showing how this initial differentiation became distorted in the 20th century as science came to dominate and colonize the other spheres, rendering a healthy differentiation into a pathological dissociation.

Obviously, examples of regression and pathology can be found in all of these trends. Moreover, we can identify other institutions of society that do not fall squarely within these categories. Religion, for example, cannot be completely subsumed within the category of morality. But as we look for the primordial influences at the heart of all forms of evolution, traces of these shaping forces can definitely be found within the collective development of culture and society. As Whitehead recognized, “Science, art, religion, and morality, take their rise from this sense of values within the structure of being.”

So although there is no conclusive proof that this threefold pattern is actually serving to organize or otherwise influence evolution in every domain of its unfolding, it seems to me that this is an intriguing proposition, which if true, could usher in a new era in our understanding of how the universe progresses. When we consider evolution as a whole, and when we begin to discern ubiquitous patterns such as the Cosmogenetic Principle, this inevitably has the positive effect of guiding us in our efforts to produce further evolution in our lives and in our world.

THE DIALECTICAL QUALITY OF

EVOLUTION'S MASTER PATTERNS

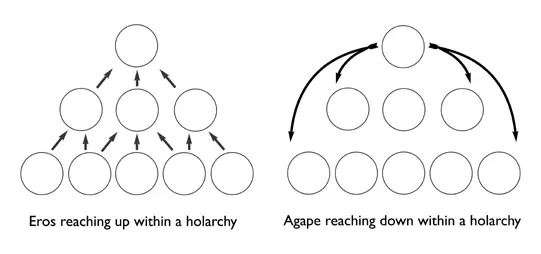

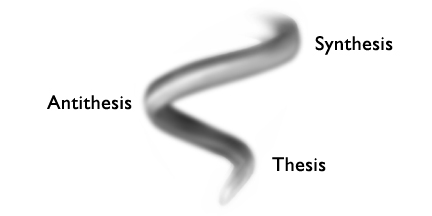

So if we are willing to allow, even if just for the sake of argument, that there is a master systemic pattern of evolution that is shaping the contours and character of evolution in each domain of its unfolding, what can we discern about this pattern as a whole? Well, when we consider both the internal and external expressions of this Cosmogenetic Principle, the first thing that becomes apparent is the pattern's dialectical character.

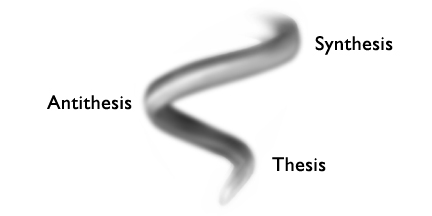

The dialectic of development

The dialectic of development

Integration and differentiation, feelings and thoughts, art and science — these categories clearly exhibit contrasting or opposing tendencies. We can also discern a certain sequence in their priority. In the dialectical movement, before something can be a part, it must first be a whole — although they work together as a system and unfold simultaneously, we can perhaps sense how integration precedes differentiation in a subtle way. Similarly, evolving consciousness exhibits feelings before it develops thoughts, and in culture the arts generally appear before the sciences. And, of course, these contrasting poles of development are always in relationship with a third element, which we have identified as consciousness in the body, free will in the mind, and morality in the organization of culture. Just as the first two elements suggest the dialectical relationship of thesis and antithesis, each of these third elements reveal a synthetic or transcendental quality. As we've discussed, consciousness is in the body but not entirely of the body, free will is in the mind but not entirely of the mind, and morality is generally recognized as being more important than either aesthetics or science.

The dialectic structure of evolution in nature, self, and culture

The dialectic structure of evolution in nature, self, and culture

So now, as promised, I want to show the connection between the dialectical quality of evolution as it is found in the distinct domains of nature, self, and culture, and the primary values of beauty, truth, and goodness. This connection is evidenced by the kinship that these values share with the differentiated expressions of evolution found in each of the domains of development we've discussed. In other words, within each of the distinct domains of objective, subjective, and intersubjective evolution we can discern a different aspect or phase of the expression of the primary values. Unity-complexity-consciousness, feeling-thought-will, and aesthetics-science-morality — each kind of evolution reveals this threefold striving for perfection in different ways. And it is by seeing how the imprint of beauty, truth, and goodness is revealed within the dialectical process of each domain's unfolding that we are led to a deeper understanding of these values, and of perfection itself.

The dialectical relationship

The dialectical relationship

of the beautiful, the true, and the good

So let's briefly consider how these “attractors of perfection” serve to shape each of the distinct domains of evolution we've discussed, starting with the value of beauty. Although beauty cannot be reduced to the material patterns of unity, although beauty is not simply integration, beauty's kinship with what I would characterize as “the pull from the center” can definitely be recognized. Beauty often arises from the different kinds of unity that find expression in the material world such as: symmetry, harmony, proportion, and self-similarity. Even originality can be understood as a form of unique wholeness or individuality — a form of unity — that is often recognized as beautiful.

Beauty, the pull from the center

Beauty, the pull from the center

These different forms of unity all exhibit beauty in their own way, but beauty's essentially spiritual quality renders it elusive to any fixed pattern. And in addition to its expression as material unity, beauty's primordial influence upon evolution can also be seen as an organizing principle in the realm of feelings and aesthetics. While beauty is certainly not the only value for these realms, it is clearly a central element.

As we consider the spiritual implications of evolution's dialectical striving for perfection, we can see how the primordial influence of beauty occupies the position of the thesis (or the tentatively completed beginning of the dialectical movement) in the way that beauty gives us a fleeting glimpse of relative actual perfection. The extent to which something is beautiful is the extent to which it is relatively complete; its evolution can proceed no further. Although it is often possible to make something more beautiful, our perception of the beauty itself arises from our intuition of the way that something exhibits the faint traces of perfection. In fact, the feelings of pleasure that accompany the experience of beauty come from the temporary relief of the relentless background pressure caused by the subtle compulsion of the incomplete — this pleasure of psychic rest arises from a beauty experience as the need to improve things is briefly satisfied.

And just as beauty reveals a kind of thesis of relative actual perfection, the value of truth occupies the position of a kind of antithesis to beauty in the way that it represents the potential for relatively more perfection. That is, truth can be expansively understood as the direction of progress by which subjective consciousness can increase its understanding of the realities of the objective and intersubjective realms that are external to it. According to Hegel, “the true … is merely the dialectical movement.”

Truth, the pull on the circumference

Truth, the pull on the circumference

This insight of Hegel's helps us see that just as beauty serves to define the present good, truth helps to define the future good, which we all strive for. That truth is a direction can best be appreciated by remembering that truth is always relative, that it is always tied to the understanding of a subject who is himself growing and developing. Subjective consciousness thus grows in truth as it increases the relative perfection with which it knows that which is outside itself — even as it increasingly recognizes the relative and contingent nature of its expanding perspectives. However, knowledge of the truth includes not only an understanding of “what's out there,” but also the knowledge of “how to get there.” The goodness of truth — the usefulness of truth — is seen in the way that its possession provides the power to improve things (and the power to avoid mistakes). The quest for truth (defined in this way) can thus be recognized as the drive to achieve greater relative potential perfection.

Just as beauty (working within the realms of feelings, aesthetics, and material unity) can be understood as the appearance of what is relatively actually perfect, truth can be contrastingly understood as the recognition of what can be potentially more perfect. The “direction of truth” — as it is pursued in our thinking, in our science, and in the unfolding of increasing complexity — can thus be envisioned as the way forward, the direction of evolution's potential for increasing perfection.

So now we come to the value of goodness. And despite the countless examples of current life conditions that cry out for improvement, I think we can perhaps agree that evolution is trending toward the good. We can see this in objective evolution's production of organisms that are increasingly aware; in subjective evolution's production of human will that is increasingly free; and in intersubjective evolution's production of cultures that are increasingly moral. Obviously, countervailing regressions or stagnations in the development of all these domains can be cited, but this does not negate the fact that increasing consciousness, free will, and morality are evident products of the evolutionary process.

Goodness occupies the position of the synthesis in the way that it defines the useful limits of beauty and truth, in the way that it mediates between the maximum extension of inclusion and transcendence relative to each other. That is, as we've seen, evolution precedes though the interplay of opposing forces, and when either of these opposing forces is privileged or extended too far, the result is pathology. The avoidance of such pathology in any developmental situation is achieved by finding the dynamic equilibrium, the right relation, that brings these dialectical forces together in progressive, synthetic harmony. Goodness is thus revealed as it contrasts with the pathology it seeks to avoid.

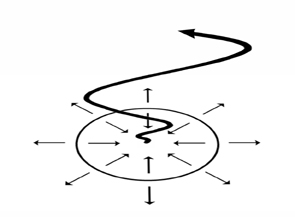

And it is from this perspective that the synthetic character of the good, which finds its expression through the harmonization of whole and part, self and other, thesis and antithesis, inclusion and transcendence, and beauty and truth, can be more fully appreciated. This dialectical relationship of inclusive transcendence can be illustrated as the systemic motion of this logarithmic spiral, growing wider as it ascends.

Goodness, inclusive transcendence

Goodness, inclusive transcendence

In light of these arguments, if we can perhaps begin to recognize how the beautiful, the true, and the good do act as subtle compass headings of universal improvement, we may then ask: What are the causal mechanisms through which these value attractors actually influence evolutionary progress? How do these ideals exert a gravitational pull on evolutionary systems? Well, the most obvious answer is that these ideals influence the choices of subjective consciousness. That is, these attractors of evolution stimulate our perfection hunger and thus directly affect our life choices, both big and small. The way that values pull us forward is well articulated by Whitehead scholar David Ray Griffin, who writes: “We are attracted to Beauty, Truth, and Goodness because these values are entertained appetitively by the Eros of the universe, whose appetites we feel.” And so it is through this understanding that we can begin to see how evolutionary progress in the internal universe comes about as Whitehead said: as the result of “gentle persuasion through love.”

Now, it is worth saying that integral philosophy is just beginning its exploration of the directions of evolution. Just as it required three hundred years for Enlightenment science to master the mysteries of the external universe (and there is obviously still much that remains unexplained), it will likewise require further development for integral consciousness to understand the “physics of the internal universe” in greater fullness. But at this point I think we can begin to detect the outlines of this Cosmogenetic Principle as it is seen functioning in each of the domains of evolution we've discussed. And I think we can also detect the self-similar quality of this master evolutionary system in the way that it shapes evolution not only in each individual domain, but also in the overarching structure that contains these three domains. That is, this threefold dialectical pattern of the Cosmogenetic Principle can be recognized in the integral worldview's reality-framing conception of the “Big Three” domains of nature, self, and culture as a whole. Thus, in light of our discussion it becomes possible to see how the objective, subjective, and intersubjective character of the developing universe is itself a reflection of evolution's dialectical advance toward increasing perfection.

The self-similar patterning of evolution's

The self-similar patterning of evolution's

Cosmogenetic Principle

in nature, self, and culture

As illustrated in this diagram, the directions of development that can be seen unfolding in each part of evolution's manifestation, can also be seen in the threefold character of evolution as a whole.

As we consider the recurring patterns that result from the influence of this ubiquitous Cosmogenetic Principle, it must be emphasized that the description of evolution in terms of these various three-part systems provides only a snapshot of a moving, developing process. In every case, the nature of these elements is more like a whole together than it is like three separate parts. But although these elements always share a systemic unity, it is in their differentiation that we see the system in action. The beautiful, the true, and the good; the objective, the subjective, and the intersubjective; and even the thesis, the antithesis, and the synthesis are like musical tones within an octave. They form each other, containing each other in harmonic relation. These differentiated elements are thus merely like the notes of the score; the actual music is found in the play of spirit in the world as it strives to achieve perfection in time. Integral philosophy's dialectical understanding of evolutionary development merely tunes our ears so as to better hear the melodies inherent in the universe's creative process.

However, it is important to state that in our attempts to discern the larger cosmological currents of our developing universe, as humans we can only glimpse faint traces of spirit's role in evolution. The primordial influences at the heart of the evolutionary impulse are not subject to being understood as mechanical or physical forces. And it is unlikely that those who ignore or deny the realities of spirit will be able to detect the way that spiritual gravity pulls us toward greater states of completion. But for those who can experience spirit, this spiritual philosophy of evolution can serve as a “natural supplement” to a wide variety of spiritual cosmologies. That which is behind the apparent threefold nature of evolution's systemic character can be explained differently by various spiritual traditions. But if those who follow different spiritual paths can find philosophical agreement about the spiritual nature of evolution, this can help us partially overcome the limitations of polite spiritual pluralism, and it can even help us make progress in our efforts to harmonize science and spirituality.

CONCLUSION

When we understand the role of values within the evolution of the internal universe, we begin to see how values partake of perfection. And when understood from an evolutionary perspective, the beautiful, the true, and the good, show themselves to be the directions of perfection. It's by creating and increasing beauty, truth, and goodness whenever and wherever we can that we make the world relatively more perfect. Thus the “revelation of evolution,” when viewed from the perspective of integral consciousness, is seen as a progressive teaching about perfection that unfolds by stages, one after another. And these “lessons of perfection” are taught to each stage of consciousness through the distinct octave of values that are the heritage of that stage. Thus as we discussed, each worldview's values can be understood as the way that it connects the decidedly imperfect human conditions that it finds here on earth with universal ideals --ideals that are translated and down-stepped into useful goals by every worldview's particular set of values.

In the realm of consciousness and culture, evolution is a two-way street. Its persuasive influences move us not only to pursue our own ascension, to improve ourselves, but also to try to make things better here on earth during our brief sojourn in this world. That is, not only are we called to rise to higher stages, but we are also called to bring the wisdom of these higher stages down to the levels that need assistance. Our world is full of trouble and suffering, and those who have attained elevated states of consciousness have a sacred duty to use this light to make a difference. And now, through the insights of integral philosophy, we have more detailed instructions on how we can actually bring more beauty, truth, and goodness into the world. Thus it seems to me that the role of human consciousness in the evolving universe, our place within the cosmic economy, is to gradually perfect ourselves by bringing perfection down to us. This is how we can directly participate in the creative act of evolution by which the universe is brought forth. This is how we become partners with spirit in the grand pageant of development wherein our personal evolution is directly linked with our participation in social and cultural evolution.

When we learn the details of what we already knew intuitively, when we recognize the dialectical dance of evolutionary progression more clearly through the use of this system of understanding, this inevitably reveals new opportunities for us to directly participate in cultural evolution. These opportunities for improvement have been there all along, but we can now begin to see them better as we are awakened to this new conception of evolution. That is, what all forms of consciousness really need, what feeds people spiritually and causes them to grow, are services of kindness, teachings of truth, and expressions of beauty. The skillful application of beauty, truth, or goodness makes any situation more evolved. And the values of beauty, truth, and goodness can be applied most skillfully when we recognize how they work together in a dialectical system. Thus, when we use integral philosophy to see how every conflict contains a transcendent synthesis that is waiting to be achieved, we are practicing the essential method of integral consciousness.

REFERENCES

[1] Aurobindo, The Future Evolution of Man (Quest Books, 1974), p. 16.

[2] Wilson, Consilience, the Unity of Knowledge (Vintage, 1998), p. 107.

[3] Laszlo, The Systems View of the World (Hampton Press, 1996), p. 44.

[4] Swimme and Berry, The Universe Story (Harper San Francisco, 1992), p. 71.

[5] Goleman, Emotional Intelligence (Bantam Books, 1995), pp. 8-9.

|

Steve McIntosh is the author of Integral Consciousness and the Future of Evolution (Paragon House 2007). He was an original member of the Integral Institute think tank, and has taught integral philosophy to a wide variety of audiences. An honors graduate of the University of Virginia Law School and the University of Southern California Business School, today McIntosh is president of Now & Zen, Inc., and director of The Project for Integral World Federation.

Steve McIntosh is the author of Integral Consciousness and the Future of Evolution (Paragon House 2007). He was an original member of the Integral Institute think tank, and has taught integral philosophy to a wide variety of audiences. An honors graduate of the University of Virginia Law School and the University of Southern California Business School, today McIntosh is president of Now & Zen, Inc., and director of The Project for Integral World Federation.