|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

David Christopher Lane David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992). SEE MORE ESSAYS WRITTEN BY DAVID LANE

The Skeptical Yogi

Part Nine: Raising the Dead, The Immortal Babaji,

and the Non-Eating Saint

David Lane

32. AND THE DEAD SHALL RISE AGAIN

As we go deeper into the Autobiography we confront even more phenomenal marvels which put our critical antennas on red alert. Here we learn of how Lahiri Mahasaya brought back a dear friend of Sri Yukteswar back to life.

“Sri Yukteswar went on to read the marvelous story of Lazarus' resurrection. At its conclusion Master fell into a long silence, the sacred book open on his knee.

'I too was privileged to behold a similar miracle.' My guru finally spoke with solemn unction. 'Lahiri Mahasaya resurrected one of my friends from the dead.'

The young lads at my side smiled with keen interest. There was enough of the boy in me, too, to enjoy not only the philosophy but, in particular, any story I could get Sri Yukteswar to relate about his wondrous experiences with his guru.

'My friend Rama and I were inseparable,' Master began. 'Because he was shy and reclusive, he chose to visit our guru Lahiri Mahasaya only during the hours of midnight and dawn, when the crowd of daytime disciples was absent. As Rama's closest friend, I served as a spiritual vent through which he let out the wealth of his spiritual perceptions. I found inspiration in his ideal companionship.' My guru's face softened with memories.

'Rama was suddenly put to a severe test,' Sri Yukteswar continued. 'He contracted the disease of Asiatic cholera. As our master never objected to the services of physicians at times of serious illness, two specialists were summoned. Amidst the frantic rush of ministering to the stricken man, I was deeply praying to Lahiri Mahasaya for help. I hurried to his home and sobbed out the story.'

'The doctors are seeing Rama. He will be well.' My guru smiled jovially.

I returned with a light heart to my friend's bedside, only to find him in a dying state.

''He cannot last more than one or two hours,' one of the physicians told me with a gesture of despair. Once more I hastened to Lahiri Mahasaya.

'The doctors are conscientious men. I am sure Rama will be well.' The master dismissed me blithely.

'At Rama's place I found both doctors gone. One had left me a note: 'We have done our best, but his case is hopeless.'

My friend was indeed the picture of a dying man. I did not understand how Lahiri Mahasaya's words could fail to come true, yet the sight of Rama's rapidly ebbing life kept suggesting to my mind: 'All is over now.' Tossing thus on the seas of faith and apprehensive doubt, I ministered to my friend as best I could. He roused himself to cry out:

'Yukteswar, run to Master and tell him I am gone. Ask him to bless my body before its last rites.' With these words Rama sighed heavily and gave up the ghost.

I wept for an hour by his beloved form. Always a lover of quiet, now he had attained the utter stillness of death. Another disciple came in; I asked him to remain in the house until I returned. Half-dazed, I trudged back to my guru.

'How is Rama now?' Lahiri Mahasaya's face was wreathed in smiles.

''Sir, you will soon see how he is,' I blurted out emotionally. 'In a few hours you will see his body, before it is carried to the crematory grounds.' I broke down and moaned openly.

''Yukteswar, control yourself. Sit calmly and meditate.' My guru retired into samadhi. The afternoon and night passed in unbroken silence; I struggled unsuccessfully to regain an inner composure.

At dawn Lahiri Mahasaya glanced at me consolingly. 'I see you are still disturbed. Why didn't you explain yesterday that you expected me to give Rama tangible aid in the form of some medicine?' The master pointed to a cup-shaped lamp containing crude castor oil. 'Fill a little bottle from the lamp; put seven drops into Rama's mouth.'

'Sir,' I remonstrated, 'he has been dead since yesterday noon. Of what use is the oil now?'

'Never mind; just do as I ask.' Lahiri Mahasaya's cheerful mood was incomprehensible; I was still in the unassuaged agony of bereavement. Pouring out a small amount of oil, I departed for Rama's house.

I found my friend's body rigid in the death-clasp. Paying no attention to his ghastly condition, I opened his lips with my right finger and managed, with my left hand and the help of the cork, to put the oil drop by drop over his clenched teeth.

As the seventh drop touched his cold lips, Rama shivered violently. His muscles vibrated from head to foot as he sat up wonderingly.

'I saw Lahiri Mahasaya in a blaze of light,' he cried. 'He shone like the sun. 'Arise; forsake your sleep,' he commanded me. 'Come with Yukteswar to see me.'

I could scarcely believe my eyes when Rama dressed himself and was strong enough after that fatal sickness to walk to the home of our guru. There he prostrated himself before Lahiri Mahasaya with tears of gratitude.

The master was beside himself with mirth. His eyes twinkled at me mischievously.

'Yukteswar,' he said, 'surely henceforth you will not fail to carry with you a bottle of castor oil! Whenever you see a corpse, just administer the oil! Why, seven drops of lamp oil must surely foil the power of Yama!'

'Guruji, you are ridiculing me. I don't understand; please point out the nature of my error.'

'I told you twice that Rama would be well; yet you could not fully believe me,' Lahiri Mahasaya explained. 'I did not mean the doctors would be able to cure him; I remarked only that they were in attendance. There was no causal connection between my two statements. I didn't want to interfere with the physicians; they have to live, too.' In a voice resounding with joy, my guru added, 'Always know that the inexhaustible Paramatman can heal anyone, doctor or no doctor.'

'I see my mistake,' I acknowledged remorsefully. 'I know now that your simple word is binding on the whole cosmos.'

As Sri Yukteswar finished the awesome story, one of the spellbound listeners ventured a question that, from a child, was doubly understandable.

'Sir,' he said, 'why did your guru use castor oil?'

'Child, giving the oil had no meaning except that I expected something material and Lahiri Mahasaya chose the near-by oil as an objective symbol for awakening my greater faith. The master allowed Rama to die, because I had partially doubted. But the divine guru knew that inasmuch as he had said the disciple would be well, the healing must take place, even though he had to cure Rama of death, a disease usually final!'

A Skeptical Analysis

If Yogananda's retelling is to be believed (and that is questionable) his guru Sri Yukteswar witnessed the resurrection of his dear friend, Rama. Apparently, Rama had contracted Asiatic cholera and became so severely ill that the doctors believed he would die within hours. Yuktestwar pleaded with his master, Lahiri Mahasaya to intervene and save his friend's life, to which he replied, “The doctors are conscientious men. I am sure Rama will be well.”

However, to Yuktestwar's shock, Rama “died.” He then ran back to his master and told him the news, deeply upset. Mahasaya, though, told his disciple to calm down and then proceeded to do nothing except meditate that afternoon and night. The next morning, we are told, the master then instructed Yuktestwar to give the “dead” Rama seven drops of crude castor oil in his mouth in the hopes of reviving the corpse and bringing it back to life. Yukteswar did as instructed and by the seventh drop Rama woke up and before he got dressed exclaimed, “I saw Lahiri Mahasaya in a blaze of light,' he cried. 'He shone like the sun. 'Arise; forsake your sleep,' he commanded me. 'Come with Yukteswar to see me.'”

As with other miracle stories in the Autobiography, this has several twists that need to be unwound. First and foremost is the odd fact that when Rama “dies” there are no doctors around and none are called in. Instead, Yukteswar tells a fellow disciple to watch over Rama's body as he goes to tell Lahiri Mahasaya the news. But when he does so his guru does nothing until the next day. Yukteswar curiously doesn't go back to see Rama, not even to inform the family, friends, and the doctors that his friend has expired.

Instead, he waits until the next day when his master then cryptically gives him castor oil. Why the wait? Why not administer it earlier if such a potion can awaken the dead?

Even one of Sri Yukteswar's younger disciples thought there was something odd about the story since he inquired “Sir, why did your guru use castor oil?”

The guru's response is nothing less than bizarre, “Child, giving the oil had no meaning except that I expected something material and Lahiri Mahasaya chose the near-by oil as an objective symbol for awakening my greater faith. The master allowed Rama to die, because I had partially doubted.”

Second, why would an esteemed guru keep Rama dead (and cause untold grief to his friends/family/doctors) just to teach his disciple, Yukteswar, a lesson in blind obedience?

The story sounds like pure and simple hagiography. Most likely Rama was not really dead and the time lapse in Yogananda's recounting is exaggerated, given the scant details we are told, especially since we hear nothing about Rama's family or doctors and that his body is left intact for a day or so.

A cynic my point out a more plausible explanation: castor oil is so nasty tasting that it woke Rama up from his deep sleep, where he looked like he was dead. Or, in his coma like state, Rama is jolted up when he has a lucid vision of his master, Lahiri Mahasaya.

Even if we actually accept Yogananda's astonishing tale—which we shouldn't, given the paucity of corroborating witnesses—it doesn't reflect well on Lahiri Mahasaya or his bizarre moral lessons. Keeping someone dead (and keeping friends and family in grief) because a disciple doubts your medical prognosis isn't the hallmark of being enlightened but of a deranged cult leader.

Rama's supposed raising from the dead is prefaced by Yukteswar exposition on how Jesus brought Lazarus back to life. He cites the Gospel of John where it is written, “Now a certain man was sick, named Lazarus. . . . When Jesus heard that, he said, This sickness is not unto death, but for the glory of God, that the Son of God might be glorified thereby.”

Yogananda and his guru assume that Lazarus' resurrection is literally true, though critical Bible scholars today doubt its veridicality, just as they question whether Jesus bodily rose out of his tomb three days after being crucified. It is no accident that the Autobiography of a Yogi's opening quote on the title page is from the New Testament wherein it states, “Except ye see signs and wonders, ye will not believe.”—John 4:48.

The Bible is chock full of fantastic miracles, but there is no compelling reason why we should believe them. As Carl Sagan was so fond of saying, “Extraordinary claims demand extraordinary evidence,” and that is in short supply both in the Bible. Most Christians forget that Jesus and Lazarus were not the only people to rise again from the dead. According to the Gospel of Matthew 27-52, lots of dead saints resurrected, “The tombs also were opened. And many bodies of the saints who had fallen asleep were raised, and coming out of the tombs after his resurrection they went into the holy city and appeared to many.”

One would imagine that if so many dead people rose from the grave and started walking to Jerusalem that it would have been so startling that future historians (non-Christian related) would have written at length about it. But, no, there are such accounts.

Similarly, it would appear that Rama's resurrection was anything but.[1]

33. BABAJI AND IMMORTALITY

Unquestionably the most incredulous story in Yogananda's Autobiography is when he introduces his reader to a Mahavatar known as Babaji, who we are told has a physical body but will never die. It is an amazing tale which has enchanted readers the world over.

“The Mahavatar is in constant communion with Christ; together they send out vibrations of redemption, and have planned the spiritual technique of salvation for this age. The work of these two fully-illumined masters—one with the body, and one without it—is to inspire the nations to forsake suicidal wars, race hatreds, religious sectarianism, and the boomerang-evils of materialism. Babaji is well aware of the trend of modern times, especially of the influence and complexities of Western civilization, and realizes the necessity of spreading the self-liberations of yoga equally in the West and in the East.

That there is no historical reference to Babaji need not surprise us. The great guru has never openly appeared in any century; the misinterpreting glare of publicity has no place in his millennial plans. Like the Creator, the sole but silent Power, Babaji works in a humble obscurity.

Great prophets like Christ and Krishna come to earth for a specific and spectacular purpose; they depart as soon as it is accomplished. Other avatars, like Babaji, undertake work which is concerned more with the slow evolutionary progress of man during the centuries than with any one outstanding event of history. Such masters always veil themselves from the gross public gaze, and have the power to become invisible at will. For these reasons, and because they generally instruct their disciples to maintain silence about them, a number of towering spiritual figures remain world-unknown. I give in these pages on Babaji merely a hint of his life-only a few facts which he deems it fit and helpful to be publicly imparted.

No limiting facts about Babaji's family or birthplace, dear to the annalist's heart, have ever been discovered. His speech is generally in Hindi, but he converses easily in any language. He has adopted the simple name of Babaji (revered father); other titles of respect given him by Lahiri Mahasaya's disciples are Mahamuni Babaji Maharaj (supreme ecstatic saint), Maha Yogi (greatest of yogis), Trambak Baba and Shiva Baba (titles of avatars of Shiva). Does it matter that we know not the patronymic of an earth-released master?

'Whenever anyone utters with reverence the name of Babaji,' Lahiri Mahasaya said, 'that devotee attracts an instant spiritual blessing.'

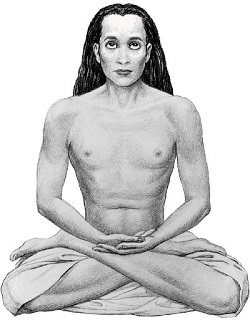

The deathless guru bears no marks of age on his body; he appears to be no more than a youth of twenty-five. Fair-skinned, of medium build and height, Babaji's beautiful, strong body radiates a perceptible glow. His eyes are dark, calm, and tender; his long, lustrous hair is copper-colored. A very strange fact is that Babaji bears an extraordinarily exact resemblance to his disciple Lahiri Mahasaya. The similarity is so striking that, in his later years, Lahiri Mahasaya might have passed as the father of the youthful-looking Babaji.

Swami Kebalananda, my saintly Sanskrit tutor, spent some time with Babaji in the Himalayas.

'The peerless master moves with his group from place to place in the mountains,' Kebalananda told me. 'His small band contains two highly advanced American disciples. After Babaji has been in one locality for some time, he says: 'Dera danda uthao.' ('Let us lift our camp and staff.') He carries a symbolic danda (bamboo staff). His words are the signal for moving with his group instantaneously to another place. He does not always employ this method of astral travel; sometimes he goes on foot from peak to peak.

Babaji can be seen or recognized by others only when he so desires. He is known to have appeared in many slightly different forms to various devotees—sometimes without beard and moustache, and sometimes with them. As his undecaying body requires no food, the master seldom eats. As a social courtesy to visiting disciples, he occasionally accepts fruits, or rice cooked in milk and clarified butter.

'Two amazing incidents of Babaji's life are known to me,' Kebalananda went on. 'His disciples were sitting one night around a huge fire which was blazing for a sacred Vedic ceremony. The master suddenly seized a burning log and lightly struck the bare shoulder of a chela who was close to the fire.'

'Sir, how cruel!' Lahiri Mahasaya, who was present, made this remonstrance.

'Would you rather have seen him burned to ashes before your eyes, according to the decree of his past karma?'

With these words Babaji placed his healing hand on the chela's disfigured shoulder. 'I have freed you tonight from painful death. The karmic law has been satisfied through your slight suffering by fire.'

On another occasion Babaji's sacred circle was disturbed by the arrival of a stranger. He had climbed with astonishing skill to the nearly inaccessible ledge near the camp of the master.

'Sir, you must be the great Babaji.' The man's face was lit with inexpressible reverence. 'For months I have pursued a ceaseless search for you among these forbidding crags. I implore you to accept me as a disciple.'

When the great guru made no response, the man pointed to the rocky chasm at his feet.

'If you refuse me, I will jump from this mountain. Life has no further value if I cannot win your guidance to the Divine.'

'Jump then,' Babaji said unemotionally. 'I cannot accept you in your present state of development.'

The man immediately hurled himself over the cliff. Babaji instructed the shocked disciples to fetch the stranger's body. When they returned with the mangled form, the master placed his divine hand on the dead man. Lo! he opened his eyes and prostrated himself humbly before the omnipotent one.

'You are now ready for discipleship.' Babaji beamed lovingly on his resurrected chela. 'You have courageously passed a difficult test. Death shall not touch you again; now you are one of our immortal flock.' Then he spoke his usual words of departure, 'Dera danda uthao'; the whole group vanished from the mountain.

An avatar lives in the omnipresent Spirit; for him there is no distance inverse to the square. Only one reason, therefore, can motivate Babaji in maintaining his physical form from century to century: the desire to furnish humanity with a concrete example of its own possibilities. Were man never vouchsafed a glimpse of Divinity in the flesh, he would remain oppressed by the heavy mayic delusion that he cannot transcend his mortality.

Jesus knew from the beginning the sequence of his life; he passed through each event not for himself, not from any karmic compulsion, but solely for the upliftment of reflective human beings. His four reporter-disciples—Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John—recorded the ineffable drama for the benefit of later generations.

For Babaji, also, there is no relativity of past, present, future; from the beginning he has known all phases of his life. Yet, accommodating himself to the limited understanding of men, he has played many acts of his divine life in the presence of one or more witnesses. Thus it came about that a disciple of Lahiri Mahasaya was present when Babaji deemed the time to be ripe for him to proclaim the possibility of bodily immortality. He uttered this promise before Ram Gopal Muzumdar, that it might finally become known for the inspiration of other seeking hearts. The great ones speak their words and participate in the seemingly natural course of events, solely for the good of man, even as Christ said: 'Father . . . I knew that thou hearest me always: but because of the people which stand by i said it, that they may believe that thou hast sent me.' During my visit at Ranbajpur with Ram Gopal, 'the sleepless saint,' he related the wondrous story of his first meeting with Babaji.

'I sometimes left my isolated cave to sit at Lahiri Mahasaya's feet in Benares,' Ram Gopal told me. 'One midnight as I was silently meditating in a group of his disciples, the master made a surprising request.

'Ram Gopal,' he said, 'go at once to the Dasasamedh bathing ghat.'

'I soon reached the secluded spot. The night was bright with moonlight and the glittering stars. After I had sat in patient silence for awhile, my attention was drawn to a huge stone slab near my feet. It rose gradually, revealing an underground cave. As the stone remained balanced in some unknown manner, the draped form of a young and surpassingly lovely woman was levitated from the cave high into the air. Surrounded by a soft halo, she slowly descended in front of me and stood motionless, steeped in an inner state of ecstasy. She finally stirred, and spoke gently.

'I am Mataji, the sister of Babaji. I have asked him and also Lahiri Mahasaya to come to my cave tonight to discuss a matter of great importance.'

A nebulous light was rapidly floating over the Ganges; the strange luminescence was reflected in the opaque waters. It approached nearer and nearer until, with a blinding flash, it appeared by the side of Mataji and condensed itself instantly into the human form of Lahiri Mahasaya. He bowed humbly at the feet of the woman saint.

Before I had recovered from my bewilderment, I was further wonder-struck to behold a circling mass of mystical light traveling in the sky. Descending swiftly, the flaming whirlpool neared our group and materialized itself into the body of a beautiful youth who, I understood at once, was Babaji. He looked like Lahiri Mahasaya, the only difference being that Babaji appeared much younger, and had long, bright hair.

Lahiri Mahasaya, Mataji, and myself knelt at the guru's feet. An ethereal sensation of beatific glory thrilled every fiber of my being as I touched his divine flesh.

'Blessed sister,' Babaji said, 'I am intending to shed my form and plunge into the Infinite Current.'

'I have already glimpsed your plan, beloved master. I wanted to discuss it with you tonight. Why should you leave your body?' The glorious woman looked at him beseechingly.

'What is the difference if I wear a visible or invisible wave on the ocean of my Spirit?'

Mataji replied with a quaint flash of wit. 'Deathless guru, if it makes no difference, then please do not ever relinquish your form.'

'Be it so,' Babaji said solemnly. 'I will never leave my physical body. It will always remain visible to at least a small number of people on this earth. The Lord has spoken His own wish through your lips.'

A Skeptical Analysis

Where to start with this narrative, which defies all logic and rationality and everything we presently know about science and the universe?

Intriguingly, I think Yogananda has revealed a secret about Babaji that casts serious doubt on his actual existence when he confesses, “Babaji can be seen or recognized by others only when he so desires.” This has far reaching implications, since an ardent devotee may mistake an ordinary yogi or sadhu believing instead that it was the immortal Babaji.

Yogananda is wrong when he writes, “That there is no historical reference to Babaji need not surprise us.”

To the contrary, if Babaji really did exist and appeared to select individuals throughout history, there should be scattered historical accounts about his existence. But none exist before Lahiri Mahasaya alleges to have first met him in 1861 and who instructed him saying, “The Kriya Yoga which I am giving to the world through you in this nineteenth century is a revival of the same science which Krishna gave, millenniums ago, to Arjuna, and which was later known to Patanjali, and to Christ, St. John, St. Paul, and other disciples.”

The fact that Lahiri Mahasaya received initiation into Kriya Yoga from Babaji, but doesn't provide any verifiable details about him is extremely troublesome, since it raises the uncomfortable issue that he may be hiding his guru's real identity. In my forty plus years of researching spiritual movements in India and in North America, anytime I learn that the founder of a new religion says that he didn't have a teacher or that his guru only appears to special acolytes I know he/she is covering something up.

I first found this out with Paul Twitchell, the founder of Eckankar, who claimed he was taught by two mysterious gurus, Sudar Singh of Allahabad and Rebazar Tarzs, a supposed five-hundred-year-old Tibetan monk living in the Himalayas. As I discovered, Sudar Singh is a fictional name that Twitchell invented to hide his past association with Kirpal Singh of Ruhani Satsang, whom later disavowed. On the other hand, Rebazar Tarzs was fictional character that the founder of Eckankar created to add a sense of mystery to his equally fictional line of Vairagi masters, which he claims dates back to Gakko on the city of Retz on the planet Venus.

Twitchell didn't want his checkered past known, so he created a mythology of Eck Masters in order to better legitimize his own self-made status.[2]

Ching Hai, who goes by the moniker Supreme Master, also tried to coverup her past by disassociating herself from her one-time guru, Thakar Singh, who initiated her into surat shabd yoga. When Ching Hai started her own ministry she more or less denied that she learned her stylized form of Quan Yin from the Indian guru and instead alleges that she received instruction from an unknown master in the Himalayan masters, but who no one has seen or met.

Gary Olsen, the founder of Masterpath, admits that he was a one-time member of Eckankar, but boldly alleges that he is a “born” saint and therefore didn't need any human guru.

The founder of Radhasoami, Shiv Dayal Singh, is also purported to never have a master, despite reports that he may have been initiated by Tulsi Sahib of Hathras and that he treated Girdhari Lal of Lucknow as a guru.

In a paper entitled, The New Panths which was first presented to the American Academy of Religion at Stanford University back in 1982, I coined the term “genealogical dissociation” to describe this pernicious habit of denying one's familial roots in order to create a new persona and a new biography.[3]

Although I don't have sufficient evidence to back up my hunch, I suspect that Lahiri Mahasaya for reasons best known to him didn't want anyone to know who precisely initiated and instructed him into Kriya Yoga. There are many alternative explanations here, including the possibility that Mahasaya had more than one teacher and simply used the name Babaji as a composite. Or, perhaps, Lahiri really did meet a guru who went by the name of Babaji but who himself was not honest about his own past and would only show up randomly or if the occasion called for it.

I fully realize that devoted followers of Yogananda's official organization, Self-Realization Fellowship, will dismiss my speculations as completely groundless. But a close analysis of Yogananda's chapter on Babaji clearly shows how easy it is for a devoted disciple to elevate a chance encounter with an obscure yogi or hermit and claim that it was really Babaji instead.

Even here in the United States I have had conversations with sincere followers of Eckankar and its many offshoots who adamantly assert that they have personally met Rebazar Tarzs, the 500-year Tibetan lama, in their neighborhood and had physical contact with him. These devotees don't doubt their experiences and scoff at critics who point out that it could easily be a projection of their own mind or case of mistaken identity, where they have an odd encounter with a stranger and then later identify the same as the ageless mystic.

In doing a meta search on the name Babaji in Yogananda's tome, his appearances are invariably shrouded in mystery. For example, Sri Yukteswar alleges that he first met Babaji at the Kumbla Mela, a vast gathering faqirs, yogis, saints, and mystics that attracts thousands from throughout India. Notice in the following sequence of events how Yukteswar seems unaware at that time that it was the Mahavatar,

“The religious fairs held in India since time immemorial are known as Kumbha Melas; they have kept spiritual goals in constant sight of the multitude. Devout Hindus gather by the millions every six years to meet thousands of sadhus, yogis, swamis, and ascetics of all kinds. Many are hermits who never leave their secluded haunts except to attend the melas and bestow their blessings on worldly men and women.

'I was not a swami at the time I met Babaji,' Sri Yukteswar went on. "But I had already received Kriya initiation from Lahiri Mahasaya. He encouraged me to attend the mela which was convening in January, 1894 at Allahabad. It was my first experience of a kumbha; I felt slightly dazed by the clamor and surge of the crowd. In my searching gazes around I saw no illumined face of a master. Passing a bridge on the bank of the Ganges, I noticed an acquaintance standing near-by, his begging bowl extended.

'Oh, this fair is nothing but a chaos of noise and beggars,' I thought in disillusionment. 'I wonder if Western scientists, patiently enlarging the realms of knowledge for the practical good of mankind, are not more pleasing to God than these idlers who profess religion but concentrate on alms.'

My smouldering reflections on social reform were interrupted by the voice of a tall sannyasi who halted before me.

'Sir,' he said, 'a saint is calling you.'

''Who is he?'

'Come and see for yourself.'

Hesitantly following this laconic advice, I soon found myself near a tree whose branches were sheltering a guru with an attractive group of disciples. The master, a bright unusual figure, with sparkling dark eyes, rose at my approach and embraced me.

''Welcome, Swamiji,' he said affectionately.

''Sir,' I replied emphatically, 'I am not a swami.'

'Those on whom I am divinely directed to bestow the title of swami never cast it off.' The saint addressed me simply, but deep conviction of truth rang in his words; I was engulfed in an instant wave of spiritual blessing. Smiling at my sudden elevation into the ancient monastic order, I bowed at the feet of the obviously great and angelic being in human form who had thus honored me.

Babaji—for it was indeed he—motioned me to a seat near him under the tree. He was strong and young, and looked like Lahiri Mahasaya; yet the resemblance did not strike me, even though I had often heard of the extraordinary similarities in the appearance of the two masters. Babaji possesses a power by which he can prevent any specific thought from arising in a person's mind. Evidently the great guru wished me to be perfectly natural in his presence, not overawed by knowledge of his identity.

Yukteswar's own penultimate words reveal in a nutshell why Babaji remains not only an enigmatic figure, but mostly likely a projection of one's own earnest desires and wishes: “Babaji possesses a power by which he can prevent any specific thought from arising in a person's mind.” As Yukteswar revealed to Lahiri Mahasaya when he saw his guru after the Kumbla Mela,

“I left Allahabad the following day and entrained for Benares. Reaching my guru's home, I poured out the story of the wonderful saint at the Kumbha Mela.

'Oh, didn't you recognize him?' Lahiri Mahasaya's eyes were dancing with laughter. 'I see you couldn't, for he prevented you. He is my incomparable guru, the celestial Babaji!'

'Babaji!' I repeated, awestruck. 'The Yogi-Christ Babaji! The invisible-visible savior Babaji! Oh, if I could just recall the past and be once more in his presence, to show my devotion at his lotus feet!'”

It is only after the Kumbla Mela and not knowing who the great saint was that Yukteswar is told later by Lahiri Mahasaya that it was, in fact, Babaji. This is a classic case of ad hoc identity transference since one could meet a wandering sage or yogi and given the right conditions believe that person to be the immortal Babaji, because he (and not a real Babaji) is a conflated presumption of their own making. Or, as in this case, one could be told by one's guru that who you met at that conference days ago wasn't who you thought it was at first but rather the Mahavatar. Even Yogananda's first time meeting with Babaji rings hollow in this regard, since it could easily be a case of mistaken identity, with the necessary caveat that we take his recounting at face value. Also notice how truly self-serving is his encounter with Babaji, since it allows Yogananda to boast that he has been personally chosen by the Mahavatar to spread the teachings of Kriya Yoga in the West.

“As I went about my preparations to leave Master and my native land for the unknown shores of America, I experienced not a little trepidation. I had heard many stories about the materialistic Western atmosphere, one very different from the spiritual background of India, pervaded with the centuried aura of saints. 'An Oriental teacher who will dare the Western airs,' I thought, 'must be hardy beyond the trials of any Himalayan cold!'

One early morning I began to pray, with an adamant determination to continue, to even die praying, until I heard the voice of God. I wanted His blessing and assurance that I would not lose myself in the fogs of modern utilitarianism. My heart was set to go to America, but even more strongly was it resolved to hear the solace of divine permission.

I prayed and prayed, muffling my sobs. No answer came. My silent petition increased in excruciating crescendo until, at noon, I had reached a zenith; my brain could no longer withstand the pressure of my agonies. If I cried once more with an increased depth of my inner passion, I felt as though my brain would split. At that moment there came a knock outside the vestibule adjoining the Gurpar Road room in which I was sitting. Opening the door, I saw a young man in the scanty garb of a renunciate. He came in, closed the door behind him and, refusing my request to sit down, indicated with a gesture that he wished to talk to me while standing.

'He must be Babaji!' I thought, dazed, because the man before me had the features of a younger Lahiri Mahasaya.

He answered my thought. 'Yes, I am Babaji.' He spoke melodiously in Hindi. 'Our Heavenly Father has heard your prayer. He commands me to tell you: Follow the behests of your guru and go to America. Fear not; you will be protected.'

After a vibrant pause, Babaji addressed me again. 'You are the one I have chosen to spread the message of Kriya Yoga in the West. Long ago I met your guru Yukteswar at a Kumbha Mela; I told him then I would send you to him for training.'

I was speechless, choked with devotional awe at his presence, and deeply touched to hear from his own lips that he had guided me to Sri Yukteswar. I lay prostrate before the deathless guru. He graciously lifted me from the floor. Telling me many things about my life, he then gave me some personal instruction, and uttered a few secret prophecies.

'Kriya Yoga, the scientific technique of God-realization,' he finally said with solemnity, 'will ultimately spread in all lands, and aid in harmonizing the nations through man's personal, transcendental perception of the Infinite Father.'

With a gaze of majestic power, the master electrified me by a glimpse of his cosmic consciousness. In a short while he started toward the door.

'Do not try to follow me,' he said. 'You will not be able to do so.'

'Please, Babaji, don't go away!' I cried repeatedly. 'Take me with you!'

Looking back, he replied, 'Not now. Some other time.'

Overcome by emotion, I disregarded his warning. As I tried to pursue him, I discovered that my feet were firmly rooted to the floor. From the door, Babaji gave me a last affectionate glance. He raised his hand by way of benediction and walked away, my eyes fixed on him longingly.”

Once more we have an incident that is highly questionable, not only because there is no way to verify if such an encounter took place but more importantly because it looks again to be a case of superimposing a divine and exalted Avatar onto what could simply be a (and very human) wandering mendicant. The late Baba Faqir Chand also used to have visions of this sort when he was young. Yet, unlike Yogananda, Faqir later came to realize that they were merely projections of his own mind and were due to his intense faith. Notice how closely Faqir's experiences echoes Yogananda's:

“My peace of mind was disturbed. I felt restless most of the time. It was a moonlit night. I was praying to the Lord and weeping bitterly. There appeared before me an aged sadhu with a long gray beard and a tambura (guitar) in his hand. Most lovingly he asked me, 'Dear child, what makes you weep?'

'I have committed four serious sins. I have known from the Hindu scriptures that God takes birth in the human form in this world. I want to see Rama and get myself pardoned for my sins,' I said.

The kind, old sadhu assured me thus, 'For you, your God in the human form is already on this earth. You will come into His contact and all your sins will be pardoned' After saying these words the sadhu disappeared.”

However, Faqir Chand, unlike Yogananda, came to understand that all such visions were not real in an objective sense but were rather the product of one's own earnest longings which manifest in moments of intense longing or hardship. In many ways Yogananda's Babaji is a spiritual Rorschach “guru holder” and depending on our upbringing and our deepest needs we can superimpose a Babaji, a Sadhu, or even a Rebazar Tarzs within it. The problem is that we never recognize our mental projections or confusions or conflations as our own. We tend, instead, to believe that they are sui generis when in truth they are not.[4]

46. THE WOMAN WHO NEVER EATS

Near the end of Yogananda's life story he meets a remarkable woman saint who alleges that she has not eaten any food or liquids for over fifty-six years. Apparently, she drank only water. Like all of the miracle stories told in the Autobiography, the closer one examines it the less believable it becomes.

“'I am the humble servant of all.' She added quaintly, 'I love to cook and feed people.'

A strange pastime, I thought, for a non-eating saint!

'Tell me, Mother, from your own lips-do you live without food?'

'That is true.' She was silent for a few moments; her next remark showed that she had been struggling with mental arithmetic. 'From the age of twelve years four months down to my present age of sixty-eight—a period of over fifty-six years-I have not eaten food or taken liquids.'

'Are you never tempted to eat?'

'If I felt a craving for food, I would have to eat.' Simply yet regally she stated this axiomatic truth, one known too well by a world revolving around three meals a day!

'But you do eat something!' My tone held a note of remonstrance.

'Of course!' She smiled in swift understanding.

'Your nourishment derives from the finer energies of the air and sunlight, and from the cosmic power which recharges your body through the medulla oblongata.'

'Baba knows.' Again she acquiesced, her manner soothing and unemphatic.

'Mother, please tell me about your early life. It holds a deep interest for all of India, and even for our brothers and sisters beyond the seas.'

Giri Bala put aside her habitual reserve, relaxing into a conversational mood.

'So be it.' Her voice was low and firm. 'I was born in these forest regions. My childhood was unremarkable save that I was possessed by an insatiable appetite. I had been betrothed in early years.'

'Child,' my mother often warned me, 'try to control your greed. When the time comes for you to live among strangers in your husband's family, what will they think of you if your days are spent in nothing but eating?'

The calamity she had foreseen came to pass. I was only twelve when I joined my husband's people in Nawabganj. My mother-in-law shamed me morning, noon, and night about my gluttonous habits. Her scoldings were a blessing in disguise, however; they roused my dormant spiritual tendencies. One morning her ridicule was merciless.

'I shall soon prove to you,' I said, stung to the quick, 'that I shall never touch food again as long as I live.'

My mother-in-law laughed in derision. 'So!' she said, 'how can you live without eating, when you cannot live without overeating?'

This remark was unanswerable! Yet an iron resolution scaffolded my spirit. In a secluded spot I sought my Heavenly Father.

'Lord,' I prayed incessantly, 'please send me a guru, one who can teach me to live by Thy light and not by food.'

A divine ecstasy fell over me. Led by a beatific spell, I set out for the Nawabganj ghat on the Ganges. On the way I encountered the priest of my husband's family.

''Venerable sir,' I said trustingly, 'kindly tell me how to live without eating.'

'He stared at me without reply. Finally he spoke in a consoling manner. 'Child,' he said, 'come to the temple this evening; I will conduct a special Vedic ceremony for you.'

This vague answer was not the one I was seeking; I continued toward the ghat. The morning sun pierced the waters; I purified myself in the Ganges, as though for a sacred initiation. As I left the river bank, my wet cloth around me, in the broad glare of day my master materialized himself before me!

'Dear little one,' he said in a voice of loving compassion, 'I am the guru sent here by God to fulfill your urgent prayer. He was deeply touched by its very unusual nature! From today you shall live by the astral light, your bodily atoms fed from the infinite current.'

Giri Bala fell into silence. I took Mr. Wright's pencil and pad and translated into English a few items for his information.

The saint resumed the tale, her gentle voice barely audible. 'The ghat was deserted, but my guru cast round us an aura of guarding light, that no stray bathers later disturb us. He initiated me into a kria technique which frees the body from dependence on the gross food of mortals. The technique includes the use of a certain mantra and a breathing exercise more difficult than the average person could perform. No medicine or magic is involved; nothing beyond the kria."

In the manner of the American newspaper reporter, who had unknowingly taught me his procedure, I questioned Giri Bala on many matters which I thought would be of interest to the world. She gave me, bit by bit, the following information:

'I have never had any children; many years ago I became a widow. I sleep very little, as sleep and waking are the same to me. I meditate at night, attending to my domestic duties in the daytime. I slightly feel the change in climate from season to season. I have never been sick or experienced any disease. I feel only slight pain when accidentally injured. I have no bodily excretions. I can control my heart and breathing. I often see my guru as well as other great souls, in vision.'

'Mother," I asked, 'why don't you teach others the method of living without food?'

My ambitious hopes for the world's starving millions were nipped in the bud.

'No.' She shook her head. 'I was strictly commanded by my guru not to divulge the secret. It is not his wish to tamper with God's drama of creation. The farmers would not thank me if I taught many people to live without eating! The luscious fruits would lie uselessly on the ground. It appears that misery, starvation, and disease are whips of our karma which ultimately drive us to seek the true meaning of life.'

"Mother," I said slowly, 'what is the use of your having been singled out to live without eating?'

'To prove that man is Spirit.' Her face lit with wisdom. 'To demonstrate that by divine advancement he can gradually learn to live by the Eternal Light and not by food.'”

A Skeptical Analysis

That a person can live without food and instead live off the sun's direct energy has become a popular ideal in some New Age circles in the United States. Even a close friend of our family once tried to convince me that it was possible to live off pure sunlight at dawn and at dusk. She even tried practicing it, but thankfully saw the errors of her way and went back to eating a relatively normal diet. Back in the 1970s I would often hear stories of very strict fruitarians living in Kauai who were trying to become breatharians, but eventually succumbed to eat fruits and vegetables.

There is a very funny and revealing story about Wiley Brooks, who founded his own breatharian movement in the 1980s but who argues that besides relying on correct breathing one should only eat a double quarter-pounder burger with cheese and a diet Coke at McDonalds since they are (he claims) non-radioactive.

Now turning our attention to Giri Bala, the non-eating saint, we are once more confronted with a highly unlikely tale which borders on the absurd. This is primarily because there is no way to absolutely know for certain whether Giri Bala goes without food, especially since she “love[s] to cook and feed people.”

It isn't cavalier to imagine that a cook might sneak a bite or two when preparing a meal. Nobody monitored Giri Bala twenty-four seven for fifty-six years, so we are completely reliant on her own testimony. It could well be that Giri Bala believed her own publicity, even as she ate and drank here and there, justifying to herself that it didn't constitute a real meal. As Richard Feynman, the distinguished physicist, warned, “The first principle is that you must not fool yourself—and you are the easiest person to fool.”

There is no scientific evidence that a person can live decades without any food whatsoever. Yes, one can fast for weeks, maybe even a month or so, but eventually the body need some type of nourishment. Of course, it doesn't have to be solid food, since one could survive on a liquid diet provided there were enough nutrients and calories.

Moreover, why is it that whenever a saint or a mystic does something completely extraordinary in the Autobiography one is “strictly commanded by [the] guru not to divulge the secret?”

David Hume's maxim is exceptionally apt and instructive here: “That no testimony is sufficient to establish a miracle, unless the testimony be of such a kind, that its. falsehood would be more miraculous, than the fact, which it endeavours to establish.”

In other words, what is more reasonable: 1) Giri Balu has defied the known laws of biology and never eaten for decades or 2) Giri Balu has ingested food and liquid but has deceived others and/or herself in the process?[5]

NOTES

[1] Concerning the reputed resurrection of Jesus Christ, Michael Shermer points out that “The biblical sources we have for the resurrection are not dependable. The gospels were written many decades after Jesus' death, and we know how unreliable human memory is for even recent events, much less those decades in the past. Perhaps the eyewitnesses saw or heard what they wanted or were expecting to see and hear. Such post-death apparitions are not uncommon among people who have lost a loved one. Maybe the story was exaggerated over multiple retellings, which is another commonplace phenomena. Perhaps the gospel authors added miraculous elements to real events in order to make them more divinely inspired and thus to elevate their religious beliefs to a higher status. . . . Ultimately, any claim that transcends and surpasses history means that science cannot, even in principle, prove or disprove it. If that is the case, then the resurrection is not a truth claim at all, but an article of faith belonging to one religion among hundreds, and with no means of determining if it is a fact or an alternative fact. In that case skepticism is warranted.”

[2] “'So who do you think Rebazar Tarzs really is?' 'Probably a composite cover name for three people: Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism, which was started 500 years ago; Sawan Singh, who was Kirpal Singh's guru; and Swami Premananda. Whereas Sudar Singh [another memorable character in Twitchell's cosmology] is...Kirpal Singh.” In The Making of a Spiritual Movement, Lane quotes many passages from Twitchell's magazine articles written in the '60s in which Twitchell cites Swami Premananda, Kirpal Singh, Meher Baba, Guru Nanak, Kabir, and even Jesus. Lane then quotes these same passages as they were later reproduced, usually word for word, in Eckankar books, with the names changed to the o Eck Masters Sudar Singh, Fubbi Quantz, Rebazar Tarzs, Lai Tsi, j and Gopal Das.” See Dodie Bellamay's cover story, “The Fraud That Is Eckankar” in the June 22, 1995 issue of the San Diego Reader.

[3] For more information on the various offshoot branches of Radhasoami, see Andrea Diem's The Guru in America.

[4] Perhaps at this juncture it is important to introduce a concept that may illuminate much of what happens when we have religious visions. It is called the Chandian Effect. As the Philosoraptor website explains it, “The Chandian Effect describes subjective visionary manifestations in which a devotee has a transpersonal encounter involving a sacred figure or form, of which the object of devotion is unaware. Faqir Chand was the first Sant Mat guru to speak at length about the unknowing aspects of such encounters. The effect designates two major factors in these manifestations: 1. The overwhelming experience of certainty that is associated with religious ecstasies and 2. The subjective projection of sacred forms/figures by a meditator or devotee without the conscious knowledge of the object beheld as the center of the experience. Chand revealed that all gurus are ignorant about the real cause of the visions and miracles attributed to them, and that because of this ignorance, the gurus gained power and devotion from followers that accredited omnipresence and omniscience to them even though these gurus were neither. Faqir Chand concluded that, 'Whosoever remembers God in whatever form, in that very form He helped his devotee.'”

[5] This episode reminds me of a conversation I had with a practitioner of Zen Buddhism who had once undergone a two-month water/broth fast in Japan. As he was telling me about the ordeal, a doctor friend of mine who was also there interrupted us and looking straight at my Zen Buddhist friend exclaimed, “Are you f…ing nuts?” To which my friend replies, “Yep, I guess I was.”

Privacy policy of Ezoic

|  David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992).

David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992).