|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

David Christopher Lane David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992). SEE MORE ESSAYS WRITTEN BY DAVID LANE

The Skeptical Yogi

Part Five: Missing Train Times, Astrological Armlets,

and Physically Charged Guru Manifestations

David Lane

15. INTUITION AND PREPARATION

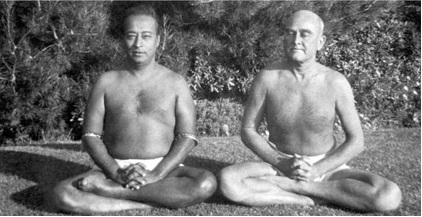

Homo sapiens often have intuitions and premonitions that we cannot logically or systematically explain. They just pop up in our brains and we sometimes react accordingly. At other times, we ignore our hunches and let them subside into the backdrop of our mind. In this chapter Yogananda describes how his guru, Sri Yukteswar, had an intuition that a few of his students were going to arrive later than usual.

“'I am pleased over your cheerful labors today and during the past week of preparations. I want you with me; you may sleep in my bed tonight.'

This was a privilege I had never thought would fall to my lot. We sat awhile in a state of intense divine tranquillity. Hardly ten minutes after we had gotten into bed, Master rose and began to dress.

'What is the matter, sir?' I felt a tinge of unreality in the unexpected joy of sleeping beside my guru.

'I think that a few students who missed their proper train connections will be here soon. Let us have some food ready.'

'Guruji, no one would come at one o'clock in the morning!'

'Stay in bed; you have been working very hard. But I am going to cook.'

At Sri Yukteswar's resolute tone, I jumped up and followed him to the small daily-used kitchen adjacent to the second-floor inner balcony. Rice and dhal were soon boiling.

My guru smiled affectionately. 'Tonight you have conquered fatigue and fear of hard work; you shall never be bothered by them in the future.'

As he uttered these words of lifelong blessing, footsteps sounded in the courtyard. I ran downstairs and admitted a group of students.

'Dear brother, how reluctant we are to disturb Master at this hour!' One man addressed me apologetically. We made a mistake about train schedules, but felt we could not return home without a glimpse of our guru.'

'He has been expecting you and is even now preparing your food.'

Sri Yukteswar's welcoming voice rang out; I led the astonished visitors to the kitchen. Master turned to me with twinkling eyes.

'Now that you have finished comparing notes, no doubt you are satisfied that our guests really did miss their train!'

I followed him to his bedroom a half hour later, realizing fully that I was about to sleep beside a godlike guru.

A Skeptical Analysis

It would appear that Yogananda (perhaps for the reader's enjoyment) has a tendency throughout his Autobiography to make even the most ordinary events appear miraculous. Often the yogis (including his own guru) he encounters he views to be superhuman, though in the guise of mere mortals. In the previous excerpt, we are informed that as they were going to sleep, Sri Yukteswar suddenly got up out of bed, dressed himself, and said to Yogananda, “I think that a few students missed their train connections.” At this, the guru, with Yogananda following suit, went into the kitchen and prepared food for their imminent arrival. Moments later, lo and behold the students showed up.

Yogananda's rhetoric is such that he wishes his readers to believe that his guru has psychic powers. Earlier in the same chapter, he comments on this, “Sri Yukteswar was a perfect human radio. Thoughts are no more than very gentle vibrations moving in the ether. Just as a sensitized radio picks up a desired musical number out of thousands of other programs from every direction.”

Yogananda even provides a footnote to support his contention,

“The 1939 discovery of a radio microscope revealed a new world of hitherto unknown rays. "Man himself as well as all kinds of supposedly inert matter constantly emits the rays that this instrument 'sees,' reported the Associated Press. 'Those who believe in telepathy, second sight, and clairvoyance, have in this announcement the first scientific proof of the existence of invisible rays which really travel from one person to another. The radio device actually is a radio frequency spectroscope. It does the same thing for cool, nonglowing matter that the spectroscope does when it discloses the kinds of atoms that make the stars. . . . The existence of such rays coming from man and all living things has been suspected by scientists for many years. Today is the first experimental proof of their existence. The discovery shows that every atom and every molecule in nature is a continuous radio broadcasting station. . . . Thus even after death the substance that was a man continues to send out its delicate rays. The wave lengths of these rays range from shorter than anything now used in broadcasting to the longest kind of radio waves. The jumble of these rays is almost inconceivable. There are millions of them. A single very large molecule may give off 1,000,000 different wave lengths at the same time. The longer wave lengths of this sort travel with the ease and speed of radio waves. . . . There is one amazing difference between the new radio rays and familiar rays like light. This is the prolonged time, amounting to thousands of years, which these radio waves will keep on emitting from undisturbed matter.'”

Was Sri Yukestwar genuinely clairvoyant? Or, can we chalk it up to the fact that when he got ready to sleep he played out various scenarios in his head, including that maybe a few of his students were stragglers and could have missed the last night train? Yet, Yogananda does not choose that route and instead elevates human intuition into a form of “soul guidance [which appears] naturally in man during those instants when his mind is calm.” And goes on to allege that a “correct hunch” is the literal transference of “thoughts to another person.”

But our hunches and intuitions are probabilistic and very often turn out dead wrong. Direct thought transference would have a measure of certainty that hunches and intuitions lack. What we don't learn in the Autobiography are all the times that gurus and masters and yogis are wrong in their precognitions. Like it or not (even if Einstein be damned), quantum mechanics implies that we live in a universe where chance is operative and much that happens is random without an ultimate design or purpose. Interestingly, Yogananda's entire philosophy is an argument against such a bleak view.

16. STARS AND THEIR INFLUENCE

Initially in this chapter, Yogananda is skeptical of astrology even though his teacher is an advocate for it, despite many practitioners of the art who are not conversant with all its purported subtleties. Later events, however, will force Yogananda to change his mind about astrology and its place in human affairs.

“'Mukunda, why don't you get an astrological armlet?'

'Should I, Master? I don't believe in astrology.'

'It is never a question of belief; the only scientific attitude one can take on any subject is whether it is true . The law of gravitation worked as efficiently before Newton as after him. The cosmos would be fairly chaotic if its laws could not operate without the sanction of human belief.

'Charlatans have brought the stellar science to its present state of disrepute. Astrology is too vast, both mathematically and philosophically, to be rightly grasped except by men of profound understanding. If ignoramuses misread the heavens, and see there a scrawl instead of a script, that is to be expected in this imperfect world. One should not dismiss the wisdom with the wise.

All parts of creation are linked together and interchange their influences. The balanced rhythm of the universe is rooted in reciprocity,' my guru continued. 'Man, in his human aspect, has to combat two sets of forces—first, the tumults within his being, caused by the admixture of earth, water, fire, air, and ethereal elements; second, the outer disintegrating powers of nature. So long as man struggles with his mortality, he is affected by the myriad mutations of heaven and earth.

Astrology is the study of man's response to planetary stimuli. The stars have no conscious benevolence or animosity; they merely send forth positive and negative radiations. Of themselves, these do not help or harm humanity, but offer a lawful channel for the outward operation of cause-effect equilibriums which each man has set into motion in the past.

A child is born on that day and at that hour when the celestial rays are in mathematical harmony with his individual karma. His horoscope is a challenging portrait, revealing his unalterable past and its probable future results. But the natal chart can be rightly interpreted only by men of intuitive wisdom: these are few.

The message boldly blazoned across the heavens at the moment of birth is not meant to emphasize fate—the result of past good and evil—but to arouse man's will to escape from his universal thralldom. What he has done, he can undo. None other than himself was the instigator of the causes of whatever effects are now prevalent in his life. He can overcome any limitation, because he created it by his own actions in the first place, and because he has spiritual resources which are not subject to planetary pressure.

Superstitious awe of astrology makes one an automaton, slavishly dependent on mechanical guidance. The wise man defeats his planets— which is to say, his past—by transferring his allegiance from the creation to the Creator. The more he realizes his unity with Spirit, the less he can be dominated by matter. The soul is ever-free; it is deathless because birthless. It cannot be regimented by stars.

Man is a soul, and has a body. When he properly places his sense of identity, he leaves behind all compulsive patterns. So long as he remains confused in his ordinary state of spiritual amnesia, he will know the subtle fetters of environmental law.

God is harmony; the devotee who attunes himself will never perform any action amiss. His activities will be correctly and naturally timed to accord with astrological law. After deep prayer and meditation he is in touch with his divine consciousness; there is no greater power than that inward protection.

'Then, dear Master, why do you want me to wear an astrological bangle?' I ventured this question after a long silence, during which I had tried to assimilate Sri Yukteswar's noble exposition.

'It is only when a traveler has reached his goal that he is justified in discarding his maps. During the journey, he takes advantage of any convenient short cut. The ancient rishis discovered many ways to curtail the period of man's exile in delusion. There are certain mechanical features in the law of karma which can be skillfully adjusted by the fingers of wisdom.

All human ills arise from some transgression of universal law. The scriptures point out that man must satisfy the laws of nature, while not discrediting the divine omnipotence. He should say: 'Lord, I trust in Thee, and know Thou canst help me, but I too will do my best to undo any wrong I have done.' By a number of means-by prayer, by will power, by yoga meditation, by consultation with saints, by use of astrological bangles-the adverse effects of past wrongs can be minimized or nullified.

"Just as a house can be fitted with a copper rod to absorb the shock of lightning, so the bodily temple can be benefited by various protective measures. Ages ago our yogis discovered that pure metals emit an astral light which is powerfully counteractive to negative pulls of the planets. Subtle electrical and magnetic radiations are constantly circulating in the universe; when a man's body is being aided, he does not know it; when it is being disintegrated, he is still in ignorance. Can he do anything about it?

"This problem received attention from our rishis; they found helpful not only a combination of metals, but also of plants and-most effective of all-faultless jewels of not less than two carats. The preventive uses of astrology have seldom been seriously studied outside of India. One little-known fact is that the proper jewels, metals, or plant preparations are valueless unless the required weight is secured, and unless these remedial agents are worn next to the skin."

"Sir, of course I shall take your advice and get a bangle. I am intrigued at the thought of outwitting a planet!"

"For general purposes I counsel the use of an armlet made of gold, silver, and copper. But for a specific purpose I want you to get one of silver and lead." Sri Yukteswar added careful directions.

"Guruji, what 'specific purpose' do you mean?"

"The stars are about to take an unfriendly interest in you, Mukunda. Fear not; you shall be protected. In about a month your liver will cause you much trouble. The illness is scheduled to last for six months, but your use of an astrological armlet will shorten the period to twenty-four days."

I sought out a jeweler the next day, and was soon wearing the bangle. My health was excellent; Master's prediction slipped from my mind. He left Serampore to visit Benares. Thirty days after our conversation, I felt a sudden pain in the region of my liver. The following weeks were a nightmare of excruciating pain. Reluctant to disturb my guru, I thought I would bravely endure my trial alone.

But twenty-three days of torture weakened my resolution; I entrained for Benares. There Sri Yukteswar greeted me with unusual warmth, but gave me no opportunity to tell him my woes in private. Many devotees visited Master that day, just for a darshan. Ill and neglected, I sat in a corner. It was not until after the evening meal that all guests had departed. My guru summoned me to the octagonal balcony of the house.

'You must have come about your liver disorder.' Sri Yukteswar's gaze was averted; he walked to and fro, occasionally intercepting the moonlight. 'Let me see; you have been ailing for twenty-four days, haven't you?'

'Yes, sir."

"Please do the stomach exercise I have taught you."

"If you knew the extent of my suffering, Master, you would not ask me to exercise." Nevertheless I made a feeble attempt to obey him.

"You say you have pain; I say you have none. How can such contradictions exist?" My guru looked at me inquiringly.

I was dazed and then overcome with joyful relief. No longer could I feel the continuous torment that had kept me nearly sleepless for weeks; at Sri Yukteswar's words the agony vanished as though it had never been.

I started to kneel at his feet in gratitude, but he quickly prevented me.

"Don't be childish. Get up and enjoy the beauty of the moon over the Ganges." But Master's eyes were twinkling happily as I stood in silence beside him. I understood by his attitude that he wanted me to feel that not he, but God, had been the Healer.

I wear even now the heavy silver and lead bangle, a memento of that day-long-past, ever-cherished-when I found anew that I was living with a personage indeed superhuman. On later occasions, when I brought my friends to Sri Yukteswar for healing, he invariably recommended jewels or the bangle, extolling their use as an act of astrological wisdom.

I had been prejudiced against astrology from my childhood, partly because I observed that many people are sequaciously attached to it, and partly because of a prediction made by our family astrologer: "You will marry three times, being twice a widower." I brooded over the matter, feeling like a goat awaiting sacrifice before the temple of triple matrimony.

"You may as well be resigned to your fate," my brother Ananta had remarked. "Your written horoscope has correctly stated that you would fly from home toward the Himalayas during your early years, but would be forcibly returned. The forecast of your marriages is also bound to be true."

A clear intuition came to me one night that the prophecy was wholly false. I set fire to the horoscope scroll, placing the ashes in a paper bag on which I wrote: "Seeds of past karma cannot germinate if they are roasted in the divine fires of wisdom." I put the bag in a conspicuous spot; Ananta immediately read my defiant comment.

"You cannot destroy truth as easily as you have burnt this paper scroll." My brother laughed scornfully.

It is a fact that on three occasions before I reached manhood, my family tried to arrange my betrothal. Each time I refused to fall in with the plans, knowing that my love for God was more overwhelming than any astrological persuasion from the past.

"The deeper the self-realization of a man, the more he influences the whole universe by his subtle spiritual vibrations, and the less he himself is affected by the phenomenal flux." These words of Master's often returned inspiringly to my mind.

Occasionally I told astrologers to select my worst periods, according to planetary indications, and I would still accomplish whatever task I set myself. It is true that my success at such times has been accompanied by extraordinary difficulties. But my conviction has always been justified: faith in the divine protection, and the right use of man's God-given will, are forces formidable beyond any the "inverted bowl" can muster.

The starry inscription at one's birth, I came to understand, is not that man is a puppet of his past. Its message is rather a prod to pride; the very heavens seek to arouse man's determination to be free from every limitation. God created each man as a soul, dowered with individuality, hence essential to the universal structure, whether in the temporary role of pillar or parasite. His freedom is final and immediate, if he so wills; it depends not on outer but inner victories.

A Skeptical Analysis

The overwhelming majority of astronomers, those trained in understanding planetary motion, star formation, and the geometry of stellar evolution, do not accept astrology as a bona fide science. To the contrary, a number of them find it to be fraught with outdated information about the cosmos and filled with psychological (and too generalist) claptrap. There are, of course, some scientists who disagree with those judgements and who champion astrology, even with its present limitations, such as the late Nobel Prize winner, Kari Mullis.

Nevertheless, Yogananda displays a healthy skepticism of this so-called science when he questions his own guru about whether or not he should wear an armlet to ward off the “negative pulls of the planets.” Yukteswar's explanation about how certain metallic armlets work is (how to say this politely?) tortured at best,

“Just as a house can be fitted with a copper rod to absorb the shock of lightning, so the bodily temple can be benefited by various protective measures. Ages ago our yogis discovered that pure metals emit an astral light which is powerfully counteractive to negative pulls of the planets. . . . This problem received attention from our rishis; they found helpful not only a combination of metals, but also of plants and—most effective of all—faultless jewels of not less than two carats. . . . One little-known fact is that the proper jewels, metals, or plant preparations are valueless unless the required weight is secured, and unless these remedial agents are worn next to the skin.”

While one can readily applaud Yukteswar's attempt to be scientific about armlets, the problem is that he doesn't properly explain how and why this or that planet can impact human beings in a negative way. If astrology wishes to be scientific it has to develop pathways to show where it can be wrong. Moreover, it must systematically explain (and test) exactly how such planetary positions are known to have this or that impact. Astrology is pseudo-psychological in ways quite similar to the pseudo-science of Freudian psychoanalysis, which accepts far too many axiomatic assumptions that have resisted being thoroughly examined.

What Yogananda presents in this chapter isn't a science of astrology and why it is accurate, but rather a theological defense of his guru's spiritual outlook. This becomes more obvious when he writes, somewhat dogmatically, “The starry inscription at one's birth, I came to understand, is not that man is a puppet of his past. Its message is rather a prod to pride; the very heavens seek to arouse man's determination to be free from every limitation. God created each man as a soul, dowered with individuality, hence essential to the universal structure, whether in the temporary role of pillar or parasite.”

As the Paranormal Encyclopedia argues,

Scientists believe that the underlying theory of astrology lacks any evidential support, and in fact is impossible. Firstly, there is no known force that can cause celestial objects to affect human life in the way claimed by astrologers (the four known forces of nature can all be ruled out). There is no evidence of any other type of force at work, leaving no mechanism for astrology. Perhaps there is some mysterious force at work, unknown to science? Even so, such a force could not work in the way astrology describes because astrology is based on a false understanding of the sizes and positions of celestial bodies. According to astrology, the influence of celestial bodies is more or less evenly spread amongst the most obvious visible heavenly objects. If an object appears brighter or moves in an interesting fashion (e.g. stationary, direct or retrograde), it will tend to be given more significance. This would have made sense 6000 years ago but we now know better. We have learnt that objects we perceive as bigger, brighter, nearer or more active are not necessarily so. Consider this example: If the outer planets have a similar level of influence to the inner planets, this would mean their level of influence is independent of distance. In turn this means that every planet in the galaxy is also influencing us. The effect of those planets would overwhelm any influence of the planets we can see.

To be sure, astrology could be tested scientifically, but invariably it doesn't pass double blinded scrutiny, such as when “astrologers are presented with a series of randomized test subjects and birth charts, then asked to match the subject with their chart. To date no studies have demonstrated an ability to do this better than random chance.”

It would appear that the reason metal armlets worked in disciples of Sri Yukteswar, excluding their “astral” light beam protection, is due to the placebo effect. Yogananda reveals as much when he acknowledges that “I wear even now the heavy silver and lead bangle, a memento of that day-long-past, ever-cherished-when I found anew that I was living with a personage indeed superhuman.”

Faith, devotion, and belief are extremely powerful touchstones and undoubtedly benefit the disciple in ways that too often are attributed to something other than his/her own emotional state of being. We are a projective creature and as such would rather attribute divine power to outer forces than to our own mentality. Astrology works in this one sense, because by accepting its principles it provides us with a sense of meaning and purpose and design in a universe that often looks devoid of all three of these attributes.

Much of Indian society has been influenced by astrological thinking and the more scientific and technologically proficient it becomes the less it has to rely on outdated and mythological modes of thought. In his Autobiography, though mostly magical in its story telling, Yogananda realizes that he must make appeal to the latest discoveries in science in order for his narrative to be convincing. But in so doing, he often mixes genuine scientific breakthroughs with philosophical musings that have the appearance of being fact-based but which are often just metaphysical speculations.

19. GURU MANIFESTATIONS

The history of religions is replete with stories about prophets, mystics, yogis, and saints who have superluminal visions of the divine. These apparitions range from beholding the Virgin Mary at Fatima to seeing Krishna walking with his gopis. In this section, Yogananda again goes on at length about divine and sudden appearances of Sri Yukteswar.

“The following day I received a post card from my guru. 'I shall leave Calcutta Wednesday morning,' he had written. 'You and Dijen meet the nine o'clock train at Serampore station.'

About eight-thirty on Wednesday morning, a telepathic message from Sri Yukteswar flashed insistently to my mind: 'I am delayed; don't meet the nine o'clock train.'

I conveyed the latest instructions to Dijen, who was already dressed for departure.

'You and your intuition!' My friend's voice was edged in scorn. 'I prefer to trust Master's written word.'

I shrugged my shoulders and seated myself with quiet finality. Muttering angrily, Dijen made for the door and closed it noisily behind him.

As the room was rather dark, I moved nearer to the window overlooking the street. The scant sunlight suddenly increased to an intense brilliancy in which the iron-barred window completely vanished. Against this dazzling background appeared the clearly materialized figure of Sri Yukteswar!

Bewildered to the point of shock, I rose from my chair and knelt before him. With my customary gesture of respectful greeting at my guru's feet, I touched his shoes. These were a pair familiar to me, of orange-dyed canvas, soled with rope. His ocher swami cloth brushed against me; I distinctly felt not only the texture of his robe, but also the gritty surface of the shoes, and the pressure of his toes within them. Too much astounded to utter a word, I stood up and gazed at him questioningly.

'I was pleased that you got my telepathic message.' Master's voice was calm, entirely normal. 'I have now finished my business in Calcutta, and shall arrive in Serampore by the ten o'clock train.'

As I still stared mutely, Sri Yukteswar went on, 'This is not an apparition, but my flesh and blood form. I have been divinely commanded to give you this experience, rare to achieve on earth. Meet me at the station; you and Dijen will see me coming toward you, dressed as I am now. I shall be preceded by a fellow passenger—a little boy carrying a silver jug.'

My guru placed both hands on my head, with a murmured blessing. As he concluded with the words, "Taba Asi," heard a peculiar rumbling sound. His body began to melt gradually within the piercing light. First his feet and legs vanished, then his torso and head, like a scroll being rolled up. To the very last, I could feel his fingers resting lightly on my hair. The effulgence faded; nothing remained before me but the barred window and a pale stream of sunlight.

I remained in a half-stupor of confusion, questioning whether I had not been the victim of a hallucination. A crestfallen Dijen soon entered the room.

'Master was not on the nine o'clock train, nor even the nine-thirty.' My friend made his announcement with a slightly apologetic air.

'Come then; I know he will arrive at ten o'clock.' I took Dijen's hand and rushed him forcibly along with me, heedless of his protests. In about ten minutes we entered the station, where the train was already puffing to a halt.

'The whole train is filled with the light of Master's aura! He is there!' I exclaimed joyfully.

'You dream so?' Dijen laughed mockingly.

'Let us wait here.' I told my friend details of the way in which our guru would approach us. As I finished my description, Sri Yukteswar came into view, wearing the same clothes I had seen a short time earlier. He walked slowly in the wake of a small lad bearing a silver jug.

For a moment a wave of cold fear passed through me, at the unprecedented strangeness of my experience. I felt the materialistic, twentieth-century world slipping from me; was I back in the ancient days when Jesus appeared before Peter on the sea?

As Sri Yukteswar, a modern Yogi-Christ, reached the spot where Dijen and I were speechlessly rooted, Master smiled at my friend and remarked:

'I sent you a message too, but you were unable to grasp it.

Dijen was silent, but glared at me suspiciously. After we had escorted our guru to his hermitage, my friend and I proceeded toward Serampore College. Dijen halted in the street, indignation streaming from his every pore.

'So! Master sent me a message! Yet you concealed it! I demand an explanation!'

'Can I help it if your mental mirror oscillates with such restlessness that you cannot register our guru's instructions?' I retorted.

The anger vanished from Dijen's face. 'I see what you mean,' he said ruefully. 'But please explain how you could know about the child with the jug.'

By the time I had finished the story of Master's phenomenal appearance at the boardinghouse that morning, my friend and I had reached Serampore College.

'The account I have just heard of our guru's powers," Dijen said, "makes me feel that any university in the world is only a kindergarten.'”

A Skeptical Analysis

I have noticed a recurring structural pattern in several of Yogananda's stories when they involve a sibling or a friend who is close in age to him. They are competitive apologues where those who question or doubt his intuitions, visions, or predictions invariably get their respective comeuppance in the end.

We first saw it with elder sister, Uma, concerning a boil, then with a kite, and now it arises again with his brother disciple (guru-bhai), Dijen, who when doubting Yogananda's intuition is eventually corrected and slightly reprimanded by Sri Yukestwar. In each of these stories, and several more, Yogananda comes out the winner.

Humans are fond of hierarchies and India is an especially multi-layered culture (see Louis Dumont's controversial Homo Hierarchicus: Essai sur le système des castes for more on caste and color). We are fond of status stratifications since in the Darwinian struggle for existence it is imperative that we find any leverage (social or otherwise) over other competitive creatures scavenging about for rare resources—be they economic or prestige-laden. Hence, it is not shocking to see Yogananda wanting to one up his companions on occasion, particularly if they question his spiritual realizations.

Once again, we confront the strange ordinariness of the miracles that abound in the day to day life recounted in the Autobiography. In this case, Sri Yukestwar is going to be an hour later than expected, which given the Indian railway system doesn't seem to be an earthshattering problem, but this necessitates a visionary (nay bodily?) intervention.

Yogananda initially gets a hunch that his guru's arrival is not going to be on the 9 o'clock train as instructed but the later 10 o'clock one. He then apparently conveys the premonition directly to Dijen who dismisses it angrily. This seems to ruffle Yogananda a bit so he sits down near the window looking out at what he refers to as the “scant sunlight.”

All of sudden, this very light turns into a beatific manifestation of Sri Yukestwar. Not only does his guru confirm Yogananda's intuition (see, Dijen, you are wrong again!) but he adds “This is not an apparition, but my flesh and blood form. I have been divinely commanded to give you this experience, rare to achieve on earth.”

What are we to make of this outrageous claim on Yogananda's part (since we don't have Yukestwar's version)? Do physical bodies truly bilocate because one is arriving an hour later than expected? Or, is this a dramatic rendition where Yogananda, quite intentionally perhaps, demonstrates his spiritual superiority over Dijen?

The contextual underlining of this story has an interesting psychological layer tying it together which forces the reader not only to doubt the “radiant, but physical form of Sri Yukteswar” showing up through window sills unannounced but to wonder why being an hour late would necessitate such a divine visitation.

Yogananda has lots of visions, but never seems to question whether they are projections of his own mind. To counter this obvious criticism, he customarily has his guru confirm, even if opaquely, that what Yogananda envisioned was generated by Sri Yukteswar himself. Yet if the vision of his guru was truly physical then why right after this event does he confess that he “remained in a half-stupor of confusion, questioning whether [he] had not been the victim of a hallucination”?

Hume's maxim is educative here, where he argues in his 1748 seminal text, An Enquiry Concerning Human Knowledge, that “That no testimony is sufficient to establish a miracle, unless the testimony be of such a kind, that its falsehood would be more miraculous, than the fact, which it endeavours to establish.” Also helpful in this regard is Thomas Jefferson's admonition, “A thousand phenomena present themselves daily which we cannot explain, but where facts are suggested, bearing no analogy with the laws of nature as yet known to us, their verity needs proofs proportioned to their difficulty.” Finally, and more simply put, we can employ Carl Sagan's rewording of Pierre-Simon Laplace's early dictum, “Extraordinary claims demand extraordinary evidence.”

Though Yogananda's tales are enthralling, he doesn't back them up with enough evidence to make them wholly believable. I don't doubt that he is certain of what he witnessed, but that certainty doesn't easily translate over to his more quizzically minded readers.

Privacy policy of Ezoic

|  David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992).

David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992).