|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

David Christopher Lane David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992). SEE MORE ESSAYS WRITTEN BY DAVID LANE

The Skeptical Yogi

Part Four: Cosmic Consciousness

And Sleepless nights

David Lane

13. SLEEPLESS IN RANBAJPUR

Occasionally in Yogananda's Autobiography we learn of remarkable experiences and events that resist being debunked, since they touch upon the wonderful plasticity of the human body/mind and what it can achieve by ardent meditation and yogic practice. The story of the sleepless saint is quite phenomenal but more believable than one might at first suspect, especially if one is conversant with long hours of interior contemplation and what it can engender.

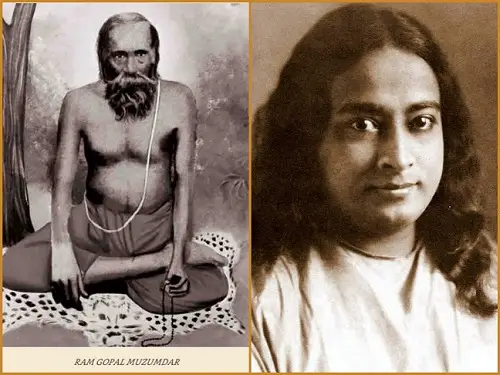

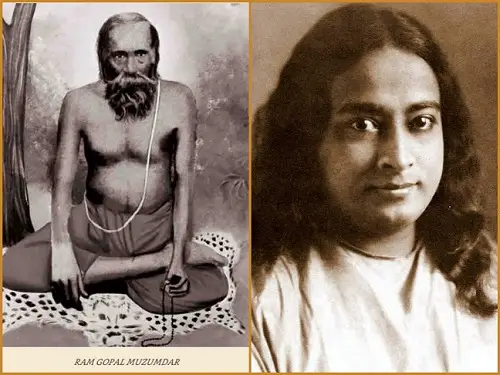

“'Young yogi, I see you are running away from your master. He has everything you need; you must return to him. Mountains cannot be your guru.' Ram Gopal was repeating the same thought which Sri Yukteswar had expressed at our last meeting.

'Masters are under no cosmic compulsion to limit their residence.' My companion glanced at me quizzically. 'The Himalayas in India and Tibet have no monopoly on saints. What one does not trouble to find within will not be discovered by transporting the body hither and yon. As soon as the devotee is willing to go even to the ends of the earth for spiritual enlightenment, his guru appears near-by.'

I silently agreed, recalling my prayer in the Benares hermitage, followed by the meeting with Sri Yukteswar in a crowded lane.

'Are you able to have a little room where you can close the door and be alone?'

'Yes.' I reflected that this saint descended from the general to the particular with disconcerting speed.

'That is your cave.' The yogi bestowed on me a gaze of illumination which I have never forgotten. 'That is your sacred mountain. That is where you will find the kingdom of God.'

His simple words instantaneously banished my lifelong obsession for the Himalayas. In a burning paddy field I awoke from the monticolous dreams of eternal snows.

'Young sir, your divine thirst is laudable. I feel great love for you.' Ram Gopal took my hand and led me to a quaint hamlet. The adobe houses were covered with coconut leaves and adorned with rustic entrances.

The saint seated me on the umbrageous bamboo platform of his small cottage. After giving me sweetened lime juice and a piece of rock candy, he entered his patio and assumed the lotus posture. In about four hours I opened my meditative eyes and saw that the moonlit figure of the yogi was still motionless. As I was sternly reminding my stomach that man does not live by bread alone, Ram Gopal approached me.

'I see you are famished; food will be ready soon.'

A fire was kindled under a clay oven on the patio; rice and dhal were quickly served on large banana leaves. My host courteously refused my aid in all cooking chores. "The guest is God," a Hindu proverb, has commanded devout observance from time immemorial. In my later world travels, I was charmed to see that a similar respect for visitors is manifested in rural sections of many countries. The city dweller finds the keen edge of hospitality blunted by superabundance of strange faces.

The marts of men seemed remotely dim as I squatted by the yogi in the isolation of the tiny jungle village. The cottage room was mysterious with a mellow light. Ram Gopal arranged some torn blankets on the floor for my bed, and seated himself on a straw mat. Overwhelmed by his spiritual magnetism, I ventured a request.

'Sir, why don't you grant me a samadhi?'

'Dear one, I would be glad to convey the divine contact, but it is not my place to do so.' The saint looked at me with half-closed eyes. 'Your master will bestow that experience shortly. Your body is not tuned just yet. As a small lamp cannot withstand excessive electrical voltage, so your nerves are unready for the cosmic current. If I gave you the infinite ecstasy right now, you would burn as if every cell were on fire.

You are asking illumination from me'" the yogi continued musingly, 'while I am wondering-inconsiderable as I am, and with the little meditation I have done--if I have succeeded in pleasing God, and what worth I may find in His eyes at the final reckoning.'

'Sir, have you not been singleheartedly seeking God for a long time?'

'I have not done much. Behari must have told you something of my life. For twenty years I occupied a secret grotto, meditating eighteen hours a day. Then I moved to a more inaccessible cave and remained there for twenty-five years, entering the yoga union for twenty hours daily. I did not need sleep, for I was ever with God. My body was more rested in the complete calmness of the superconsciousness than it could be by the partial peace of the ordinary subconscious state.

The muscles relax during sleep, but the heart, lungs, and circulatory system are constantly at work; they get no rest. In superconsciousness, the internal organs remain in a state of suspended animation, electrified by the cosmic energy. By such means I have found it unnecessary to sleep for years. The time will come when you too will dispense with sleep.'

'My goodness, you have meditated for so long and yet are unsure of the Lord's favor!' I gazed at him in astonishment. 'Then what about us poor mortals?'

'Well, don't you see, my dear boy, that God is Eternity Itself? To assume that one can fully know Him by forty-five years of meditation is rather a preposterous expectation. Babaji assures us, however, that even a little meditation saves one from the dire fear of death and after-death states. Do not fix your spiritual ideal on a small mountain, but hitch it to the star of unqualified divine attainment. If you work hard, you will get there.'

Enthralled by the prospect, I asked him for further enlightening words. He related a wondrous story of his first meeting with Lahiri Mahasaya's guru, Babaji. Around midnight Ram Gopal fell into silence, and I lay down on my blankets. Closing my eyes, I saw flashes of lightning; the vast space within me was a chamber of molten light. I opened my eyes and observed the same dazzling radiance. The room became a part of that infinite vault which I beheld with interior vision.

'Why don't you go to sleep?'

'Sir, how can I sleep in the presence of lightning, blazing whether my eyes are shut or open?'

'You are blessed to have this experience; the spiritual radiations are not easily seen.' The saint added a few words of affection.

At dawn Ram Gopal gave me rock candies and said I must depart. I felt such reluctance to bid him farewell that tears coursed down my cheeks.

'I will not let you go empty-handed.' The yogi spoke tenderly. "I will do something for you."

He smiled and looked at me steadfastly. I stood rooted to the ground, peace rushing like a mighty flood through the gates of my eyes. I was instantaneously healed of a pain in my back, which had troubled me intermittently for years. Renewed, bathed in a sea of luminous joy, I wept no more. After touching the saint's feet, I sauntered into the jungle, making my way through its tropical tangle until I reached Tarakeswar.

There I made a second pilgrimage to the famous shrine, and prostrated myself fully before the altar. The round stone enlarged before my inner vision until it became the cosmical spheres, ring within ring, zone after zone, all dowered with divinity.

I entrained happily an hour later for Calcutta. My travels ended, not in the lofty mountains, but in the Himalayan presence of my Master.”

A Skeptical Analysis

Meditation works wonders. But such wonders are scientifically verifiable and don't necessitate a radically new paradigm to understand why.

In previous chapters I have questioned Yogananda's magniloquent laced stories, because they cater to credulous readers who are not well acquainted with a religious world filled with charlatans who pass off their hocus pocus antics as if they were the real deal.

But in this chapter, where he discusses meeting Ram Gopal, a so-called “sleepless” saint, my aporetic antennae is partially disarmed.

Why? Because it is not out of the realm of possibility (and probability) that a yogi steeped in meditation can forego sleep as we know it. While it is certainly true that sleep is necessary for human survival, this elemental need can be met by those who have the ability to penetrate deeply within their own consciousness. When one is absorbed in contemplation it can, at various stages, include parts of the sleep cycle to such a degree that one can remain fully conscious, even while the dream world brilliantly manifests all around.

While deep meditation can at differing levels be likened to lucid dreaming, it is a step beyond that since one doesn't lose awareness during the process but is fully awake within, even as the body goes through its biochemical modulations.

At first this may seem parapsychological or outside of the ken of neuroscience, but this is not the case at all. Indeed, even atheistic/agnostic neuroscientists, such as Sam Harris, know from their own personal adventures in this area that the mind/body complex can undergo amazing transformations during prolonged meditational practices. It is for this reason that even the most reductionistic of academic institutions (such as M.I.T.) have pioneered a number of remarkable studies on the effects that meditation can have on the brain.

Paradoxically, research has shown that meditation can increase melatonin levels within the body which are conducive for longer sleep cycles. While smaller periods of meditation may be helpful for those suffering from insomnia, it can also benefit those who meditate for much longer stretches of time since they too “sleep” but without losing awareness. They get the chemical benefits that accompany sleep without being completely “knocked out” and lost in dream landscapes.

Of course, we don't know for certain whether Ram Gopal always went without sleep (we are, lest we forget, relying on second-hand reports), but we do know that it is possible provided that deep meditation facilitates and allows the biochemical showering that is vital for normal human functioning. Simply put, certain forms of deep meditation include sleep cycles during the process, even if one retains a keen sense of lucidity throughout.

Ram Gopal, using religious language (but which have biochemical referents), explains why he didn't need sleep since he was getting a much longer lasting rest via meditation. As he pointed out to Yogananda, “My body was more rested in the complete calmness of the superconsciousness than it could be by the partial peace of the ordinary subconscious state. The muscles relax during sleep, but the heart, lungs, and circulatory system are constantly at work; they get no rest. In superconsciousness, the internal organs remain in a state of suspended animation, electrified by the cosmic energy. By such means I have found it unnecessary to sleep for years.”

Interestingly, when Ram Gopal made these claims the scientific world hadn't yet fully explored what meditation had to offer. In the past two decades, remarkable strides have been made to give credence to some of the more outrageous claims made by Tibetan and Indian yogis for centuries.

Jolene Creighton writing for Neoscope has summarized some of the more remarkable scientific findings about meditation and its impact on the body/brain[1]:

- In a study published in Clinical Psychology Review, researchers at Boston University and Harvard Medical School found that the technique helps alleviate anxiety and allows individuals to better cope with stressful situations.

- Dr. Fadel Zeidan, assistant professor of neurobiology and anatomy at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center, found that meditation helps individuals cope with, and better tolerate, physical pain. This work was published in the Journal of Neuroscience.

- In a 2015 study published in Frontiers in Psychology, researchers from UCLA found that individuals who meditate over extended periods have more gray matter volume in their brains than those that do not. The work looked at individuals who been meditating for an average of 20 years, and the impact was pronounced.

- A 2011 study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, which was conducted by Yale University, discovered that meditation decreases activity in the default mode network (DMN) in the brain. In the paper, the team noted that this reveals the actual biological impact of meditation and helps bring to light “a unique understanding of possible neural mechanisms of meditation.”

- Sara Lazar, a neuroscientist at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, recently conducted work which found that individuals who meditate ultimately have more gray matter in the frontal cortex and, most notably, that this gray matter is preserved in spite of aging. The significance is overwhelming. As Lazar asserts in an interview with the Washington Post, “It's well-documented that our cortex shrinks as we get older—it's harder to figure things out and remember things. But in this one region of the prefrontal cortex, 50-year-old meditators had the same amount of gray matter as 25-year-olds.”

- Scientists assert that using proprioceptive input (also know as deep touch pressure (DTP)) to ground your body is helpful when attempting to reach a meditative state. Research has shown that this kind of pressure results in a reduction in cortisol levels and an increase in serotonin production, decreasing your heart rate and blood pressure. Thus, the relaxed physical state that comes from peroprioceptive input can make it easier to achieve a calm mental state that's conducive to meditation, and one of the most effective ways to get this proprioceptive input is by using a weighted blanket.

As Amber Martin, an occupational therapist from Utica College, notes, “peroprioceptive input is good for pretty much everyone and anyone. It can be very calming and organizing.” By helping you reach a state of peaceful relaxation more quickly, the blankets make it easier for you to take advantage of every valuable moment of meditation before you have to return to the busy world outside your mind.

- There's little debate in the science regarding the benefits of meditation. According to research published in the Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, meditation has been linked to reduced feelings of depression, anxiety, and physical pain.

On a more personal note, I have been a shabd yoga meditator for the past forty plus years and I have noticed that prolonged hours of meditation have allowed me to sleep much less than before and still feel just as rested, if not more invigorated.

Furthermore, I observed that after four straight hours of meditation—and as one gets sleepy—one becomes keenly aware of the hypnagogic transitional state, which precedes deep sleep and REM dreaming. All sorts of phantasmagorical images come alive and if one can retain awareness then these give away to a series of dream revelries. Usually, we witness these unconsciously and without a keen sense of awareness, but if one meditates proficiently and skillfully one has the ability to remain transpicuous to what is arising. I can personally attest that such a possibility is not merely academic since I too have had moments where meditation allows one a portal into the dream world without losing self-awareness.

Ram Gopal's account, though sounding unbelievable at first, is actually attainable (at least to some degree) by almost anyone well versed in the practice of deep meditation. In other words, yoga and neuroscience are not strange bedfellows.

14. COSMIC CONSCIOUSNESS

This chapter is clearly one of my favorites and though utterly surreal, its focuses on what the human mind is capable of and how one can directly experience illuminated states of consciousness that are usually inaccessible.

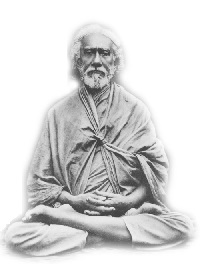

Sri Yukteswar

Sri Yukteswar

“A few mornings later I made my way to Master's empty sitting room. I planned to meditate, but my laudable purpose was unshared by disobedient thoughts. They scattered like birds before the hunter.

'Mukunda!' Sri Yukteswar's voice sounded from a distant inner balcony.

I felt as rebellious as my thoughts. "Master always urges me to meditate," I muttered to myself. "He should not disturb me when he knows why I came to his room."

He summoned me again; I remained obstinately silent. The third time his tone held rebuke.

'Sir, I am meditating,' I shouted protestingly.

'I know how you are meditating,' my guru called out, 'with your mind distributed like leaves in a storm! Come here to me.'

Snubbed and exposed, I made my way sadly to his side.

'Poor boy, the mountains couldn't give what you wanted.' Master spoke caressively, comfortingly. His calm gaze was unfathomable. 'Your heart's desire shall be fulfilled.'

Sri Yukteswar seldom indulged in riddles; I was bewildered. He struck gently on my chest above the heart.

My body became immovably rooted; breath was drawn out of my lungs as if by some huge magnet. Soul and mind instantly lost their physical bondage, and streamed out like a fluid piercing light from my every pore. The flesh was as though dead, yet in my intense awareness I knew that never before had I been fully alive. My sense of identity was no longer narrowly confined to a body, but embraced the circumambient atoms. People on distant streets seemed to be moving gently over my own remote periphery. The roots of plants and trees appeared through a dim transparency of the soil; I discerned the inward flow of their sap.

The whole vicinity lay bare before me. My ordinary frontal vision was now changed to a vast spherical sight, simultaneously all-perceptive. Through the back of my head I saw men strolling far down Rai Ghat Road, and noticed also a white cow who was leisurely approaching. When she reached the space in front of the open ashram gate, I observed her with my two physical eyes. As she passed by, behind the brick wall, I saw her clearly still.

All objects within my panoramic gaze trembled and vibrated like quick motion pictures. My body, Master's, the pillared courtyard, the furniture and floor, the trees and sunshine, occasionally became violently agitated, until all melted into a luminescent sea; even as sugar crystals, thrown into a glass of water, dissolve after being shaken. The unifying light alternated with materializations of form, the metamorphoses revealing the law of cause and effect in creation.

An oceanic joy broke upon calm endless shores of my soul. The Spirit of God, I realized, is exhaustless Bliss; His body is countless tissues of light. A swelling glory within me began to envelop towns, continents, the earth, solar and stellar systems, tenuous nebulae, and floating universes. The entire cosmos, gently luminous, like a city seen afar at night, glimmered within the infinitude of my being. The sharply etched global outlines faded somewhat at the farthest edges; there I could see a mellow radiance, ever-undiminished. It was indescribably subtle; the planetary pictures were formed of a grosser light.

The divine dispersion of rays poured from an Eternal Source, blazing into galaxies, transfigured with ineffable auras. Again and again I saw the creative beams condense into constellations, then resolve into sheets of transparent flame. By rhythmic reversion, sextillion worlds passed into diaphanous luster; fire became firmament.

I cognized the center of the empyrean as a point of intuitive perception in my heart. Irradiating splendor issued from my nucleus to every part of the universal structure. Blissful amrita, the nectar of immortality, pulsed through me with a quicksilver-like fluidity. The creative voice of God I heard resounding as Aum, the vibration of the Cosmic Motor.

Suddenly the breath returned to my lungs. With a disappointment almost unbearable, I realized that my infinite immensity was lost. Once more I was limited to the humiliating cage of a body, not easily accommodative to the Spirit. Like a prodigal child, I had run away from my macrocosmic home and imprisoned myself in a narrow microcosm.

My guru was standing motionless before me; I started to drop at his holy feet in gratitude for the experience in cosmic consciousness which I had long passionately sought. He held me upright, and spoke calmly, unpretentiously.

'You must not get overdrunk with ecstasy. Much work yet remains for you in the world. Come; let us sweep the balcony floor; then we shall walk by the Ganges.'

I fetched a broom; Master, I knew, was teaching me the secret of balanced living. The soul must stretch over the cosmogonic abysses, while the body performs its daily duties. When we set out later for a stroll, I was still entranced in unspeakable rapture. I saw our bodies as two astral pictures, moving over a road by the river whose essence was sheer light.

'It is the Spirit of God that actively sustains every form and force in the universe; yet He is transcendental and aloof in the blissful uncreated void beyond the worlds of vibratory phenomena,' Master explained. 'Saints who realize their divinity even while in the flesh know a similar twofold existence. Conscientiously engaging in earthly work, they yet remain immersed in an inward beatitude. The Lord has created all men from the limitless joy of His being. Though they are painfully cramped by the body, God nevertheless expects that souls made in His image shall ultimately rise above all sense identifications and reunite with Him.'

The cosmic vision left many permanent lessons. By daily stilling my thoughts, I could win release from the delusive conviction that my body was a mass of flesh and bones, traversing the hard soil of matter. The breath and the restless mind, I saw, were like storms which lashed the ocean of light into waves of material forms-earth, sky, human beings, animals, birds, trees. No perception of the Infinite as One Light could be had except by calming those storms. As often as I silenced the two natural tumults, I beheld the multitudinous waves of creation melt into one lucent sea, even as the waves of the ocean, their tempests subsiding, serenely dissolve into unity.

A master bestows the divine experience of cosmic consciousness when his disciple, by meditation, has strengthened his mind to a degree where the vast vistas would not overwhelm him. The experience can never be given through one's mere intellectual willingness or open-mindedness. Only adequate enlargement by yoga practice and devotional bhakti can prepare the mind to absorb the liberating shock of omnipresence. It comes with a natural inevitability to the sincere devotee. His intense craving begins to pull at God with an irresistible force. The Lord, as the Cosmic Vision, is drawn by the seeker's magnetic ardor into his range of consciousness.”

A Skeptical Analysis

Although Yogananda's description about cosmic consciousness is effusive and filled with sonorous evocations about the Divine, it seems obvious that the experience was transformative. What makes his account so compelling, even if he can be pardoned for some of his turgid prose, is that it dovetails with other mystics from around the world who have had similar out-of-body ecstasies. Yogananda's momentous rapture reminds one of modern NDE accounts, where dying patients are transported to a heavenly realm and enter a dark tunnel and see a scintillating light and more.

While we may doubt or question how Yogananda ultimately interpreted his experience of cosmic consciousness, I am of the strong opinion that Yogananda did indeed have a mystical vision and that his guru was the chief catalyst behind it. I don't say this lightly or to elevate Yogananda's spiritual status, but only to highlight what consciousness is capable of producing under the right conditions and given the right cues. This doesn't mean by extension that such illuminations were not brain induced or beyond the ken of neuroscience to understand them. Rather, it is to realize that extraordinary states of awareness are possible and that yoga, meditation, prayer, and other methods are powerful tools to unleash hidden corridors of the human mind.

Yogananda provides us with the contextual setting for where, when, how, and why he was ready for such a transcendent illumination. First, he had been thwarted in his efforts to run away and meet Himalayan masters; second, he had met his guru and began regular and guided sadhana; third, he was slightly reprimanded by Ram Gopal, the “sleepless” saint for his continued pilgrimages when what he needed was back at his home ashram. These factors, plus Yogananda's intense faith and desire, served as tipping points in his spiritual evolution. His emotional and mental kindling were preset and thus when Sri Yukteswar tapped him on the chest above his heart it served as an immediate unleashing of his spiritual potential.

Yogananda, to his credit, provides us with enough physical clues about what transpired that we can better understand how such a wondrous experience could happen and why others in different mystical traditions may have had similar excursions.

Notice that right after his guru touches him, Yogananda talks about how his body freezes up which is so intense that he “became immovably rooted.” This feeling of physical paralysis is a common precursor in those undergoing a mystical ecstasy. The feeling of numbness in the body, but specifically in the peripheral nervous system, is, according to Indian sages, a preliminary “acid test” which confirms that the numinous exteriorization is genuine. Yogananda then mentions that “breath was drawn out of my lungs as if by some huge magnet. Soul and mind instantly lost their physical bondage, and streamed out like a fluid piercing light from my every pore.” This sounds very reminiscent of what happens when one has a near-death experience, though his description is more vivid and detailed and most likely has been garnished in the final editing process before publication.

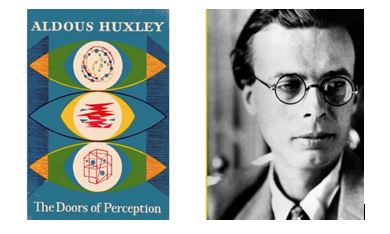

His account also sounds remarkably similar to reports from those who have ingested psychedelic drugs, such as LSD 25, mescaline, MDMA, ketamine, and DMT. Aldous Huxley in his groundbreaking tome, The Doors of Perception (1954), writing less than a decade after Autobiography of a Yogi was published, speaks in enraptured tones after ingesting mescaline,

I continued to look at the flowers, and in their living light I seemed to detect the qualitative equivalent of breathing -but of a breathing without returns to a starting point, with no recurrent ebbs but only a repeated flow from beauty to heightened beauty, from deeper to ever deeper meaning. Words like "grace" and "transfiguration" came to my mind, and this, of course, was what, among other things, they stood for. My eyes traveled from the rose to the carnation, and from that feathery incandescence to the smooth scrolls of sentient amethyst which were the iris. The Beatific Vision, Sat Chit Ananda, BeingAwareness-Bliss-for the first time I understood, not on the verbal level, not by inchoate hints or at a distance, but precisely and completely what those prodigious syllables referred to. And then I remembered a passage I had read in one of Suzuki's essays. "What is the Dharma-Body of the Buddha?" ('"the Dharma-Body of the Buddha" is another way of saying Mind, Suchness, the Void, the Godhead.) The question is asked in a Zen monastery by an earnest and bewildered novice. And with the prompt irrelevance of one of the Marx Brothers, the Master answers, "The hedge at the bottom of the garden." "And the man who realizes this truth," the novice dubiously inquires, '"what, may I ask, is he?" Groucho gives him a whack over the shoulders with his staff and answers, "A golden-haired lion."

It had been, when I read it, only a vaguely pregnant piece of nonsense. Now it was all as clear as day, as evident as Euclid. Of course the Dharma-Body of the Buddha was the hedge at the bottom of the garden. At the same time, and no less obviously, it was these flowers, it was anything that I - or rather the blessed Not-I, released for a moment from my throttling embrace - cared to look at. The books, for example, with which my study walls were lined. Like the flowers, they glowed, when I looked at them, with brighter colors, a profounder significance. Red books, like rubies; emerald books; books bound in white jade; books of agate; of aquamarine, of yellow topaz; lapis lazuli books whose color was so intense, so intrinsically meaningful, that they seemed to be on the point of leaving the shelves to thrust themselves more insistently on my attention.”

Gerald Edelman, the Nobel Prize winning scientist, quotes Emily Dickinson in his preface to Wider than the Sky: The Phenomenal Gift of Consciousness, where she shares a vision of consciousness that resonates with mystics East and West,

Yogananda is in good company when he euphorically writes, “The Spirit of God, I realized, is exhaustless Bliss; His body is countless tissues of light. A swelling glory within me began to envelop towns, continents, the earth, solar and stellar systems, tenuous nebulae, and floating universes. The entire cosmos, gently luminous, like a city seen afar at night, glimmered within the infinitude of my being. The sharply etched global outlines faded somewhat at the farthest edges; there I could see a mellow radiance, ever-undiminished. It was indescribably subtle; the planetary pictures were formed of a grosser light.”

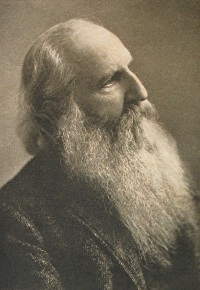

For instance, compare the preceding passages with Richard Maurice Bucke's introduction to his book on Cosmic Consciousness,

Richard Maurice Bucke

Richard Maurice Bucke

“It was in the early spring, at the beginning of his thirty-sixth year. He and two friends had spent the evening reading Wordsworth, Shelley, Keats, Browning, and especially Whitman. They parted at midnight, and he had a long drive in a hansom (it was in an English city). His mind, deeply under the influence of the ideas, images and emotions called up by the reading and talk of the evening, was calm and peaceful. He was in a state of quiet, almost passive enjoyment. All at once, without warning of any kind, he found himself wrapped around as it were by a flame-colored cloud. For an instant he thought of fire, some sudden conflagration in the great city; the next, he knew that the light was within himself. Directly afterwards came upon him a sense of exultation, of immense joyousness accompanied or immediately followed by an intellectual illumination quite impossible to describe. Into his brain streamed one momentary lightning-flash of the Brahmic Splendor which has ever since lightened his life; upon his heart fell one drop of Brahmic Bliss, leaving thenceforward for always an aftertaste of heaven. Among other things he did not come to believe, he saw and knew that the Cosmos is not dead matter but a living Presence, that the soul of man is immortal, that the universe is so built and ordered that without any peradventure all things work together for the good of each and all, that the foundation principle of the world is what we call love and that the happiness of every one is in the long run absolutely certain. He claims that he learned more within the few seconds during which the illumination lasted than in previous months or even years of study, and that he learned much that no study could ever have taught.

The illumination itself continued not more than a few moments, but its effects proved ineffaceable; it was impossible for him ever to forget what he at that time saw and knew; neither did he, or could he, ever doubt the truth of what was then presented to his mind.”

The skeptic, who has not had such experiences, will undoubtedly look askance at such narratives, impugning their veridicality with the tiresome trope that “they are just brain hallucinations,” forgetting in the process that even our own waking state is the product of symphonic neural activity. What we take to be real at any moment is also predicated upon cerebral processes for which we have no direct access. Therefore, given how little we know about consciousness and how/why it emerges, it behooves us not to prematurely dismiss mystical encounters and what they can teach us about our evolutionary heritage.

The danger is when we prematurely believe that our inner, subjective experiences can only be interpreted along already given theological trajectories. Yes, human experience is far reaching and has many unexplored byways, but we do ourselves no service when we ad hoc dismiss alternative interpretations too early and too easily because they contravene our religious upbringings.

Notes

[1] Jolene Creighton, "Harvard Neuroscientist: Meditation Reduces Stress and Literally Changes Your Brain", Neoscope, May 09 2017.

Privacy policy of Ezoic

|

David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992).

David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992).