|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992). David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992).SEE MORE ESSAYS WRITTEN BY DAVID LANE The Golden GlobesThe Reality/Non-Reality of Out-of-Body ExperiencesDavid Lane and Andrea Diem-LaneBaba Faqir Chand, Terence McKenna, and Sam Harris

Yes, intertheoretic reductionism can on occasion go too far and end up providing us with less, not more, information about a significant event.

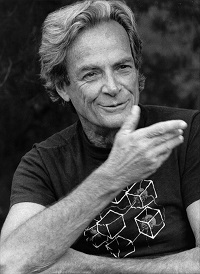

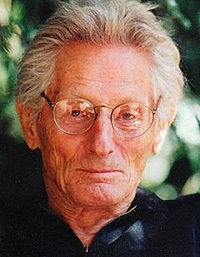

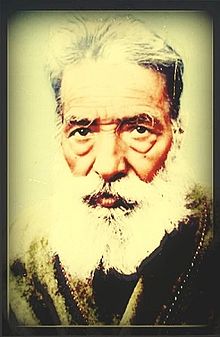

Richard Feynman is well known and well regarded for his contributions to quantum electrodynamics (QED) for which he won a Nobel Prize in physics in 1965 along with Sin-Itiro Tomonaga and Julian Schwinger. But what may come as a surprise to those not conversant with his life and work is that Richard Feynman was also deeply interested in out of body experiences and became adept at it after becoming acquainted with John Lilly, a pioneer in the field of dolphin research who had developed sensory deprivation tanks in the 1950s. Despite becoming friends, Feynman and Lilly parted company with each other over how best to interpret inner experiences while out of the body. Feynman argued that all such phenomena were hallucinatory in nature, whereas Lilly felt that they revealed something far beyond the rational mind and the restrictive limits of empirical science. Richard Feynman recalls how he first met John Lilly,  Richard Feynman (d. 1988) “I used to give a lecture every Wednesday over at the Hughes Aircraft Company, and one day I got there a little ahead of time, and was flirting around with the receptionist, as usual, when about half a dozen people came in - a man, a woman, and a few others. I had never seen them before. The man said, "Is this where Professor Feynman is giving some lectures?" While Feynman took up Lilly's offer, he resisted the mystical overlay that surrounded the deprivation tank hoopla, calling such “mystic hokey poke,” “wick-wack things” and, most curiously, “all kinds of gorp.” Yet, Feynman found his experiences deeply fascinating and enriching, despite his skeptical interpretations. With repeated sessions in the salt water tank, he became adept at leaving his body and experiencing all sorts of intriguing phenomena. As Feynman recounts, I had many types of out-of-the-body experiences. One time, for example, I could "see" the back of my head, with my hands resting against it. When I moved my fingers, I saw them move, but between the fingers and the thumb I saw the blue sky. Of course that wasn't right; it was a hallucination. But the point is that as I moved my fingers, their movement was exactly consistent with the motion that I was imagining that I was seeing. The entire imagery would appear, and be consistent with what you feel and are doing, much like when you slowly wake up in the morning and are touching something (and you don't know what it is), and suddenly it becomes clear what it is. So the entire imagery would suddenly appear, except it's unusual, in the sense that you usually would imagine the ego to be located in front of the back of the head, but instead you have it behind the back of the head. Throughout it all Feynman remains the scientific skeptic, even as he becomes increasingly disoriented by what occurs while experiencing an O.B.E. He also continually attempts to differentiate what is happening from mere dreaming. Feynman elaborates: One of the things that perpetually bothered me, psychologically, while I was having a hallucination, was that I might have fallen asleep and would therefore be only dreaming. I had already had some experience with dreams, and I wanted a new experience. It was kind of dopey, because when you're having hallucinations, and things like that, you're not very sharp, so you do these dumb things that you set your mind to do, such as checking that you're not dreaming. So I perpetually was checking that I wasn't dreaming by - since my hands were often behind my head - rubbing my thumbs together, back and forth, feeling them. Of course I could have been dreaming that, but I wasn't: I knew it was real. After the very beginning, when the excitement of having a hallucination made them "jump out," or stop happening, I was able to relax and have long hallucinations. Notice that Feynman never actually believes that his experiences are anything more than fantastic, even if extraordinarily lucid, hallucinations—a word he uses repeatedly when describing his exteriorizations. Because of this dismissive attitude, Lilly reprimanded Feynman in a letter and accused him of being non-scientific. As I wrote in The Neural Paradox,  John Lilly (d. 2001) Interestingly, when John Lilly had mystical experiences of what he perceived as other worldly beings in his sensory deprivation tank (after taking mind-altering drugs, such as Ketamine), he argued strongly for their ontological objectivity. Whereas, Richard Feynman, the Nobel prize winner in physics for his work on quantum electrodynamics, who had similar experiences as Lilly (they were friends) labeled his out of body excursions as “hallucinations.” Feynman's categorical dismissal miffed Lilly who then criticized him in a personal letter with the terse rebuttal, “you stopped being a scientist the instant you said that word, hallucination.” Feynman countered Lilly's assertion by pointing out that whatever out-of-body experiences he was having (and Feynman recalls becoming very good at) didn't correlate to the outside world, even when undergoing the dissociation he thought they did. It was for this reason that he tried to convince Lilly that “the imagination that things are real does not represent true reality. If you see golden globes, or something, several times, and they talk to you during your hallucination and tell you they are another intelligence, it doesn't mean they're another intelligence; it just means that you have had this particular hallucination.... I believe there's nothing in hallucinations that has anything to do with anything external to the internal psychological state of the person who's got the hallucination.” Feynman's critique of Lilly as outlined above can be codified in just one of his sentences when he writes, “If you see golden globes, or something, several times, and they talk to you during your hallucination and tell you they are another intelligence, it doesn't mean they're another intelligence; it just means that you have had this particular hallucination.” Feynman's skepticism may cause disbelieving cackles among those who believe that what is experienced while having an OBE is something more than phantasmagoria. Yet, could Feynman's hallucinatory hypothesis hold true for religious visions in general? This got me to thinking of how a visionary mystic such as Sri Ramakrishna would respond to someone like Feynman, since the Bengali saint had visions weekly, if not daily, during his lifetime. As the Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna retells the story, But he did not have to wait very long. He has thus described his first vision of the Mother: "I felt as if my heart were being squeezed like a wet towel. I was overpowered with a great restlessness and a fear that it might not be my lot to realize Her in this life. I could not bear the separation from Her any longer. Life seemed to be not worth living. Suddenly my glance fell on the sword that was kept in the Mother's temple. I determined to put an end to my life. When I jumped up like a madman and seized it, suddenly the blessed Mother revealed Herself. The buildings with their different parts, the temple, and everything else vanished from my sight, leaving no trace whatsoever, and in their stead I saw a limitless, infinite, effulgent Ocean of Consciousness. As far as the eye could see, the shining billows were madly rushing at me from all sides with a terrific noise, to swallow me up! I was panting for breath. I was caught in the rush and collapsed, unconscious. What was happening in the outside world I did not know; but within me there was a steady flow of undiluted bliss, altogether new, and I felt the presence of the Divine Mother." On his lips when he regained consciousness of the world was the word "Mother". Would the latest findings in neuroscience disabuse Ramakrishna of spiritual ecstasies, since manifestations of Kali, the Divine Mother, were actually the result of his undiagnosed temporal lobe epilepsy and not divine revelations as he so ardently believed? Or, is such undiagnosed medical reductionism going too far?  Baba Faqir Chand It is one of those curious coincidences that prop up now and then when studying the lives of great men and women that the year Sri Ramakrishna died (1886) is the same year that another intense visionary in India, Baba Faqir Chand, was born. While Ramakrishna died when he was only 50 years old, Faqir lived until he was 95. Yet what they both had in common was the remarkable ability to have spiritual visions almost at will. The fundamental difference, however, is that Faqir came to believe that all such experiences were projections of his own mind and were in themselves illusory. He, like Feynman, didn't think such images were real. As Faqir explains in his revealing book, The Secret of Secrets, “My form manifests in America, Africa and in different parts of India, but I remain ignorant about it. Even I remain unaware of the persons who meditate on my form. I have removed this mask of fancy whereas some other gurus and religious heads take undue advantage of this myth from their ignorant followers. I do not blame the religious heads and these gurus, because the followers too feel flattered by this loot and they do not want to get rid of this illusion.” Researchers such as John Lilly and Terence McKenna have long argued that dismissing inner experiences (whether by ingesting psychedelics or by meditation) as mere hallucinations misses the larger issue and prematurely downplays their potential significance. As McKenna argues, All these themes are woven around DMT, possibly because DMT creates a microcosm of this very shift of epochs in the experience of a single individual. It seems to lift the perceiving mind out of the confines of ordinary space and time and give a glimpse of the largest frame of being possible. When Plato remarked that "Time is the moving image of Eternity," he made a statement every voyage into the DMT space reinforces. Like the shift of epoch called the apocalypse and anticipated by religious hysterics, DMT seems to illuminate the regions beyond death. And what is the dimension beyond life as illuminated by DMT? If we can trust our own perceptions, then it is a place in which thrives an ecology of souls whose stuff of being is more syntactical than material. It seems to be a nearby realm inhabited by eternal elfin entelechies made entirely of information and joyous self-expression. The afterlife is more Celtic fairyland than existential nonentity; at least that is the evidence of the DMT experience. The problem with Feynman's categorical “it's all hallucinations” hypothesis is that it lacks nuance and can in itself prevent one from further exploring the borderlands of the mind. Even though Faqir eventually felt that all inner visions were illusory, he still persisted in meditating since he found that he could have experiences beyond light and sound. Yet, what caught Feynman's attention most was that his visions were invariably intertwined with what he had been thinking about previously. He also argued that we shouldn't confuse our imaginary voyages with reality. Apparently in his discussions with Lilly he didn't persuade him to his side, try as he might. Recalls Feynman, One of the questions I thought about was whether hallucinations, like dreams, are influenced by what you already have in your mind - from other experiences during the day or before, or from things you are expecting to see. The reason, I believe, that I had an out-of-body experience was that we were discussing out-of-body experiences just before I went into the tank. And the reason I had a hallucination about how memories are stored in the brain was, I think, that I had been thinking about that problem all week. I had considerable discussion with the various people there about the reality of experiences. They argued that something is considered real, in experimental science, if the experience can be reproduced. Thus when many people see golden globes that talk to them, time after time, the globes must be real. My claim was that in such situations there was a bit of discussion previous to going into the tank about the golden globes, so when the person hallucinating, with his mind already thinking about golden globes when he went into the tank, sees some approximation of the globes - maybe they're blue, or something - he thinks he's reproducing the experience. Faqir would agree with Feynman that religious visions are the product of previously undigested experiences we have in the waking state, which get astrally magnified when we alter our state of consciousness. For instance, Faqir once had a most remarkable vision of his eventual guru, Maharishi Shiv Brat Lal, before ever meeting him. In his vision, he even received the correct address to his guru's ashram and began writing him monthly. Initially Faqir was convinced that this extraordinary experience was a miracle, since he saw and learned things that were completely new to him. However, years later Faqir thought more deeply about the subject and came to believe that he must have come upon Shiv Brat Lal's picture and address days or weeks before his visions and unconsciously incorporated such into his startling religious perception. Faqir's explanation actually makes sense in light of the fact that Shiv Brat Lal was a prolific writer and had published a number of books and magazines that were widely circulated. Sam Harris, the noted author and neuroscientist, severely critiqued Dr. Eben Alexander for alleging that he had proof that heaven exists because he had a NDE that convinced him of it. As Alexander vividly describes it (as cited by Harris in his article, “This Must Be Heaven”), “I was a speck on a beautiful butterfly wing; millions of other butterflies around us. We were flying through blooming flowers, blossoms on trees, and they were all coming out as we flew through them… [there were] waterfalls, pools of water, indescribable colors, and above there were these arcs of silver and gold light and beautiful hymns coming down from them. Indescribably gorgeous hymns. I later came to call them “angels,” those arcs of light in the sky. I think that word is probably fairly accurate…. Then we went out of this universe. I remember just seeing everything receding and initially I felt as if my awareness was in an infinite black void. It was very comforting but I could feel the extent of the infinity and that it was, as you would expect, impossible to put into words. I was there with that Divine presence that was not anything that I could visibly see and describe, and with a brilliant orb of light…. They said there were many things that they would show me, and they continued to do that. In fact, the whole higher-dimensional multiverse was this incredibly complex corrugated ball and all these lessons coming into me about it.” To wit, Harris then goes on to cite Terence McKenna's own experience under DMT, pointing out the obvious similarities between the two and suggesting that Alexander has confused a neurological state for an ontological one. Writes Harris, “Alexander believes that his E. coli-addled brain could not have produced his visions because they were too “intense,” too “hyper-real,” too “beautiful,” too “interactive,” and too drenched in significance for even a healthy brain to conjure. He also appears to think that despite their timeless quality, his visions could not have arisen in the minutes or hours during which his cortex (which surely never went off) switched back on. He clearly knows nothing about what people with working brains experience under the influence of psychedelics. Nor does he know that visions of the sort that McKenna describes, although they may seem to last for ages, require only a brief span of biological time. Unlike LSD and other long-acting psychedelics, DMT alters consciousness for merely a few minutes. Alexander would have had more than enough time to experience a visionary ecstasy as he was coming out of his coma (whether his cortex was rebooting or not). Does Alexander know that DMT already exists in the brain as a neurotransmitter? Did his brain experience a surge of DMT release during his coma? This is pure speculation, of course, but it is a far more credible hypothesis than that his cortex “shut down,” freeing his soul to travel to another dimension. As one of his correspondents has already informed him, similar experiences can be had with ketamine, which is a surgical anesthetic that is occasionally used to protect a traumatized brain.” There is no denying that humans have the capacity of for extraordinary states of consciousness (regardless of how they are generated), but the contentious issue is a perennial one: how best to interpret them? Even though I tend to align myself with a more skeptical attitude to all such inner phenomena, sometimes the reductionistic approach can border on the inane, as what happened when Carl Sagan in Broca's Brain tried to reduce Near Death Experiences to vague birth memories of one's obstetrician, apparently forgetting in the process that those undergoing Cesarean birth report the same kind of NDEs as those born vaginally. Yes, intertheoretic reductionism can on occasion go too far and end up providing us with less, not more, information about a significant event. While I applaud Feynman's skepticism (he was willing to do the experiment and willing to listen to contrarian ideas), lumping each and every OBE as a hallucination (even if somewhat accurate) can be misleading, especially since much valuable data can be garnered within such states about how consciousness works when deprived of incoming stimuli from the five senses. Lest we forget, our current waking state is also the direct result of our neural symphony and though augmented by varying data streams (light, sound, touch, smell, etc.) it too has hallucinatory features, as has been repeatedly documented in various studies in visual perception. As for myself, I have noticed that deep meditation can reveal aspects of the mind that cannot be so readily garnered in a purely “eyes open” waking state. While such numinous encounters may tell me nothing about the world “outside of my head” they do tell me much about how our consciousness works as a virtual simulator and how what we see and hear within can take on overwhelming certainty of its own. Perhaps the real danger is when we conflate our OBEs and NDEs with external realities, neglecting in the process that they may be distinct realms that needn't overlap, at least not epistemologically. I have often stressed in my College and University courses that the original sin of humankind wasn't necessarily taking a bite of the forbidden fruit from the Tree of Knowledge in the Garden of Eden, but rather when we mistakenly believed that our present, past, or future neural state actually revealed the “real” state of the universe. We are knowledge bounded creatures, who for evolutionary reasons have taken whatever current state we are in (as partial as it may be) as something whole and correct and because of this are caught within magical worlds of our own making, where image becomes reality and where effect becomes cause. I am not quite sure how we can get beyond this brain-generated impasse, except to realize that in the library of consciousness there are multitude of potential states of awareness. All we have to do is open our mind to them and be sure not to exaggerate their reach.

“I believe there's nothing in hallucinations that has anything to do with anything external to the internal psychological state of the person who's got the hallucination. But there are nevertheless a lot of experiences by a lot of people who believe there's reality in hallucinations.” --Richard Feynman

|