|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992). David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992).SEE MORE ESSAYS WRITTEN BY DAVID LANE Atomic SpiritualityTom Blake's Natural PhilosophyDavid LaneINTRODUCTION

“There is no sentiment in Nature, but there [is] plenty of necessity.” —Tom Blake, February 3, 1991

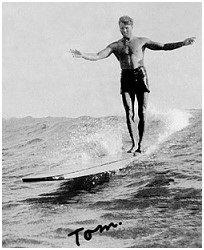

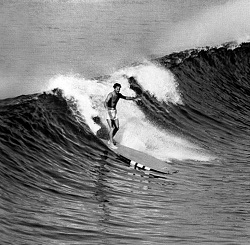

Tom Blake changed the face of surfing and has long been lauded as one of the true pioneers and innovators in the sport. Although much has been written about him and his contributions (culminating in Gary Lynch's magisterial biography of him, Tom Blake: The Uncommon Journey of a Pioneer Waterman, published in 2001), very little work has been done on Tom Blake's Einsteinian philosophy. This is a shame, since though Blake was not formally educated (he never graduated high school due to the devastating influenza epidemic that swept the world in 1918 and 1919), he was an astute observer of nature and had a deep understanding of science and its implications on such perennial questions concerning ethics, God, and the goal of human life. The essence of Tom Blake's philosophical outlook is best captured in his book, Voice of the Atom, an engaging narrative that centers on his conversations with a young nomadic wanderer named Anthony. Yet, there are also other scattered writings, particularly letters that he wrote to friends over the years, that provide a wider glimpse into Blake's thinking that are invaluable. Tom Blake was not a man of many words, but what he did write, occasionally in terse and epigrammatic phrases, are pregnant with meaning. As such, they offer us a tantalizing clue behind this enigmatic man, who in the course of a somewhat lonely existence influenced the lives of millions who mimicked Tom Blake's lifestyle, even as they remained oblivious to his reasoning behind it.

This book is an attempt to better understand Tom Blake's outlook on life, which is much more than simply an ocean lifestyle, although that too plays a dramatic and elemental part. To accomplish this aim, I have decided to focus primarily on Blake's own words, attempting the best I can to unpack some of his more compacted thoughts and ideas. Calling this “a surfer's philosophy” may at first give some pause, since for many surfers are perceived as a motley crew more bent on partying than on philosophizing. While some of that stereotype is true (and some of it in a very positive sense), a larger purview shows that focusing on the ocean and what it has to offer is an illuminated pathway to gain some hard earned wisdom about the vagaries of life. While it is impractical and misleading to pigeonhole all surfers into a certain type, there are, nevertheless, some core elements that appear common across the surface. First and foremost is a love for the simple act of riding waves, whether short or long boarding, whether body-boarding or bodysurfing—the list of wave-riding vehicles is indeterminate. Second, and this is where philosophy plays a part, surfers have tended to adopt a different kind of lifestyle than most, one that is invariably dependent on the ocean's ever-changing tides, moods, and conditions. A dedicated surfer has to be open to fleeting moments and be ready within hours, if not minutes, to change course lest he or she miss out on a glassy session, offshore winds, or a peaking swell. In other words, a surfer has to be attuned to the present moment and keenly aware of how previous swells operated and of potential future trajectories, keeping in mind the fundamental physics of position and momentum. Take for example, how a southern California surfer must navigate an energy pattern that first emerged 10 days prior off the coast of New Zealand. As the winds hit 60 mph or more across a vast area of sea, waves emerge and do their rhythmic march to distant lands, getting groomed and more properly defined during the march. Imagine you are sitting atop your board at 56th street at Newport Beach waiting for a set to reach just beyond the jetty. Two things have to be in harmony—your position and your momentum. You have to coordinate your surfboard with the incoming wave and time it just right. If you are too far in or out (or worse, too far behind the bowl), that unique pattern of cresting water molecules will explode its pent up energy across the sand bar and you will shake your head in regret, unless there is another one outside. A surfer is a water physicist. If he or she is not, then riding a wave is not possible. Granted that the surfer in question may not know the mathematical equations underlying why ocean waves form (such as “Wave Energy = Wind Speed x Wind Duration x Fetch Distance”), but experientially she must bodily adapt as if such laws were written in her muscular memory. Tom Blake was a scientist of surfing and, as such, took a very empirical approach to the subject. This led him to all sorts of remarkable innovations that allowed him more freedom in the ocean than what was thought possible. Within the limits of his time period (fiberglass, though invented as “glass wool” in the early 1930s, had only become commercially viable until much later), Tom Blake utilized what Stuart Kaufmann has insightfully called the adjacent possible. Ever observant and with a remarkable eye for detail, Blake applied his extensive knowledge of the ocean and available building materials to create the “hollow surf and paddle board, water proof camera housing, a prototypical sail board, a surfboard with a built-in keel (skeg/fin), and such lifeguarding rescue devices as the torpedo buoy and rescue ring.” Blake was also a champion swimmer and waterman, winning the swimming world record in the ten mile open in 1922, the Pacific Coast Surfriding in 1928, and the Catalina Paddleboard race in 1932. But far beyond these accomplishments, Blake established a lifestyle around the sea that focused on what was ultimately important in life, perhaps best epitomized by his famous quip, “lessen the overhead.” Tom Blake lived a non-conventional life, married once for a short period, had no offspring, and never really settled down until his final years back in his state of birth, Wisconsin. Yet, this most remarkable of men, by pursuing an oceanic vision has transformed the lives of millions, not merely by his words but precisely how he chose to live. For surfers around the world today are, to some measure, the lineal descendants of Tom Blake's ideas, encompassed as they were by a life fully lived where the guiding principle is perhaps best summarized by an old Hawaiian proverb, “Never turn your back to the ocean.” “Science has proved that each atom, with its mass and energy system, is a complete unit of nature, with all the divine attributes, sustaining power and intelligence found in all substance, in all things. Thus, the atom may be usefully defined and thought of [as] a part of God; with the energy force of nature or God. Humanity reacts to this force. As man is but an aggregation of atoms in molecular form, the atom becomes man's ultimate identity: the order, rhythm, harmony and power of the atom are identified as man's rightful deeds. The voice of the atom tells us God is part of everything, everything, part of one God: one universal nature.” A Scientific View

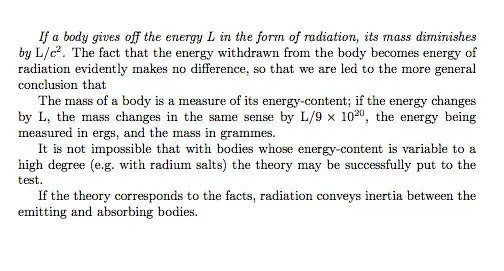

It is obvious in reading Voice of the Atom that Tom Blake was deeply influenced by Albert Einstein's theories, particularly his groundbreaking 1905 paper entitled, Does the inertia of a body depend upon its energy-content?, which explains the equivalence of mass and energy in the famous equation E=MC2. Later Blake would summarize this law of physics simply as “Nature=God” which he later permanently etched in sandstone overlooking his favorite bay. Interestingly, Blake's pantheism dovetails with the brilliant 17th century philosopher Baruch Spinoza, who argued in his magnus opus, Ethics, Demonstrated in Geometrical Order, that there was one universal substance permeating throughout the universe such that “Although each particular thing be conditioned by another particular thing to exist in a given way, yet the force whereby each particular thing perseveres in existing follows from the eternal necessity of God's nature.” Blake defines God's nature via atomic theory explaining that “Scientists now agree that the atom consists of many states of being. They have proved that while the mass and energy of the atom change identity, it does not disintegrate into nothing.” While Tom Blake does employ religious language, particularly when talking about God, his definition of a Supreme Power is much more radical and heretical than what most Christians would accept. For instance, Blake doesn't believe that Jesus resurrected from the dead, but instead holds that “Logic, reason, and science have established that no man truly dead has ever returned to a living state of being.” Blake theorizes that Jesus Christ didn't actually die on the cross, per se, but rather that he only “appear to expire” and was later revived by his friends and because of this was able to walk out the tomb. Whether this is historically true or not is still up for debate since we simply don't have enough information to make any absolute judgments (except, of course, if one is a dogmatic believer or skeptic). But the key underlying point that Blake was driving at has less to do with the specific question of Jesus' purported resurrection, but with the much larger issue of how to explain miracles in an age of science. To this, Blake provides a telling example analogizing that if we ventured back one thousand years ago and saw a jet plane flying overhead, we would think of it as a miracle and be perplexed by its existence. But that was only because we didn't understand the exact science and mechanics behind why a jet of such weight could fly so fast through the air. Simply put, there was nothing supernatural about it, even though we remain impressed by it technological wizardly. As Arthur C. Clarke, author of 2001: A Space Odyssey, quipped, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” On this score Blake and Clarke see eye to eye and thus Blake clearly concludes, “Therefore, we must deny the preconceived notions of miracles. . . .” Blake envisions a much different Christianity and a much different interpretation of what Jesus Christ actually did. As Blake opines, “No man—and Jesus was a man—has ever, or ever will, appear in a living state after dying. That would be in the realm of the supernatural, or an unnatural concept, which was disproved by Einstein in his mass energy equivalence assessment of things.” Blake goes on to argue that all such miracle stories relating to Christ are mere embellishments that detract from the deeper message of compassion for those less than our self. Blake even suggests that the resurrection accounts of Jesus may have been doctored by later scribes, “The truth is obscure, and the events after the crucifixion, may well have been the combined effort of the scribes, who recorded their views long years (an estimated forty or more) after his death, to create the ideal man of compassion that millions of humanity have had faith in down through the centuries and even today.” For Blake, there is an underlying unity behind nature and he doesn't want to speak of a God that requires a belief in something transmundane. He approvingly quotes Emerson who writes, “Truth is the summit of being.” And upon this Blake adds, “The atom, nature, God, and morality equal Truth; the first class way to go.” Blake clearly champions a scientific way of thinking over naively believing in religious mythology, arguing that “truth, rather than myth, should be established, and as I said before, computerized and available when needed.” In the Voice of the Atom, which centers on his dialogue with Anthony in the desert (who represents an idealized Christian trying to imitate the life of Christ), Blake wants to persuade his young acquaintance that with more time and consideration many of the old and outdated rules of orthodox religion will fall away as superstitious nonsense. While he doesn't necessarily advocate free love, Blake sees sex in a much more normal light and admonishes his young friend (who wants to be celibate) to think more reasonably about the subject. Blake realizes that humans are evolved to procreate and in a very telling aside comments, “Lonely in middle age and old age is the man who fathers no children and especially sad, the woman who fails to fulfill her nature in this respect.” Dovetailing with his fellow religionists who believe in eternal life, Blake too suggests that we live eternally. But it is not what one usually imagines. Instead of a bodily resurrection into heaven or a voyage into unchartered astral planes, Blake focuses on Einstein's theories concerning the interchangeability of matter and energy where he exclaims, “Emphatically, yes, we do continue to exist by the compulsive laws of nature and God, by changing back into the atom kingdom as a necessary and useful part of nature or God; when we die we are not turned out of the universe; merely returned to the good earth; to our original atomic state, more peaceful, stable and harmonious than stress-full human state.” Blake envisions this way of thinking as liberating and in this purview he dovetails with such luminaries as Goethe, Emerson, Nikola Tesla, Carl Jung, Walt Whitman, Heraclitus and Lao Tzu, among many others. For Blake Nature is not a problem, as such, but the very essence of our existence and necessitates that we understand its vagaries. Look carefully enough and the deep mysteries of life unravel themselves, since whatever the universe is so are we. There is no duality in Blake's worldview, just confused misapprehensions by humans who are not observant and honest enough to confess the obviousness that surrounds us. Blake realizes that some may not agree with his positive spin concerning the afterlife, but he is nothing if not optimistic when he writes, “embrace the sublime and comforting concept of being reincarnated into a useful and grand eternal atomic state of being, our true and rightful, and I might add, inevitable heritage, and where all is well.” Circle of Compassion“I knew I didn't want to be killed and I figured all animals felt the same way. I have been a vegetarian since 1924.”

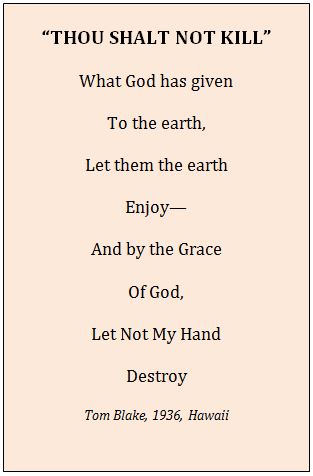

Today being a vegetarian or a vegan is much more commonplace than it was in years past. This is due to a variety of influences, not the least of which is a growing awareness that eliminating red meat is a health promoting practice. Thus it is quite remarkable that Tom Blake decided to become a vegetarian in 1924 at the age of twenty-two. At that time, there were very few people who abstained from meat and those who did were often disparaged as strange “health nuts” or, worse, backward “Hindoos.” It appears Blake was influenced by the burgeoning health movement that was growing at that time in Southern California. Recollects Blake, “The San Fernando Valley had many fruit orchards and the owners would let you have all the fruit you could find after the pickers went through. It was at this time I was introduced to the personal health movement and became a vegetarian. I depended on my health for my swimming and lifeguard work.” Although health was a primary concern for Blake's switch to a vegetarian diet, it also dovetailed with his overall ethic of increasing his circle of compassion to include other life forms. As Blake wrote, “Israel's Judaism, India's Hinduism, Islam, Buddhism, China's Confucianism, Christianity, in essence, carry the same theme.” Blake also saw his vegetarianism as dovetailing with what he took as the first real commandment of Judaism and Christianity: “Thou shalt no kill.” He also emphasized the “Golden Rule, as taught by Christ, as well as the writings of the ancient philosophers and Hindus; the work of Eherat and Jackson also had their influence. Now, all those good teachings blend with the findings of the Science of Nutrition, proving in fact that which man has known by instinct from time immortal.” At the age of 41 years, Blake provided The American Vegetarian with a distillation of his dietary habits: “As a member of the U.S. Coast Guard for 14 months, serving 'somewhere south of Alaska,' I can say we get the finest food in the world, and plenty of it. I pass up the meat, fish, and fowl, but the variety of other food is extensive, and sufficient to balance a diet. There is a salad or fruit at every meal, as well as butter and milk.” In his talks with the young Anthony in the desert later in his life, Blake elaborated on vegetarianism and his ethical reasoning behind it: “I consider being a vegetarian a prime factor in my well-being; the main reason for surviving to the age of 85. Vegetarian meals are more healthful than the denser, chemical laden foods, which tend to clog up arteries and capillaries, when one overindulges. Vegetarian foods are more forgiving. It also eliminates the need to kill, or share the burden of responsibility for the killing of God's creatures. . . . Thousands of years ago vegetarianism was practiced by Hindu people of India. . . . All this points up a way of seeking the better life, and encouraging others to do the same. In a word, respect for life, your own, and all of the earth's living creatures. They too are of nature's kingdom.” Blake's moral arc was grounded in the science of his day and he felt strongly that the best of religion could be substantiated by a deep study of the ocean. He was a realist, however, and didn't overly romanticize nature, since he understood all too well its cruelties. As Blake pointed out, “Nature is without sentiment.” Although Blake doesn't mention Darwin or evolution in any length in his writings, it is clear that he understood what the theory portended and how life—temporary as it is—was a struggle for existence, especially where there is a scarcity of resources. But despite nature's ultimate indifference, Blake's philosophy is a very positive one and he was willing to focus on a longer view of things, accepting in the process that man's former religious ideas have been superseded by a more accurate and robust scientific understanding, underlining “that the old meaning of spiritualism died when Einstein identified energy as equivalent of mass. Then energy became real and replaced the mystery of spiritualism. Anything and everything has to be considered and dealt with in our daily lives. The ethic and moral of Jesus was compassion for all life.” Blake was not an absolutist in his philosophy, since he clearly realized that “compassion must be balanced by compulsion to survive.” Because of this one must follow certain instinctual laws, while attempting to transcend our more animalistic tendencies. For Blake, this entails being willing to pay the price for certain errors of judgment and learning how to align one's self with the natural ebb and flow of differing circumstances. This earth, according to Blake, will never be a utopia but we can optimize the best that it has to offer while minimizing those aspects that are damaging or harmful. As Blake realistically explains, “We must pay a price for all error or transgression of nature's rules; our so-called sins are not forgiven by nature [or] God, therefore we must know truth from error, right from wrong an impossible goal at our present stage of knowledge, for any one person. Among the living species, we find a mutual respect and a certain sense of security for members among their own kind—should we expect less of humanity? I believe not, for there must be a certain togetherness, and trust but not necessarily love for each other. For me the word love is reserved for special relationships such as those that exist between parent and child but respect for all else.” Blake, in a somewhat unique (even if unusual coupling), wants to marry Jesus' high moral code with Einstein's atomic theory and suggests that both are necessary for an enlightened life. It should be noted, however, that Blake is not a Christian apologist, since he doesn't hold to Biblical inerrancy or any of the standard dogmas. Rather, he emphasizes those features that can be ascertained without indulging in mere theological speculation. In this regard, Blake is more in accord with Aldous Huxley's perennial philosophy that sees an undercurrent of truth and its applicability in almost all the world's religions. Blake even holds a karmic view on thought and reaction (something that is common in such Eastern religions as Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, and Sikhism) as he employs science to support his contention that “Einstein's cosmic energy field of matter is real, something that affects us. We cannot escape its reward or its sting; much, but not all, depending on our own personal conduct and actions. Surely, sow and reap, in kind—sooner or later—has ageless truth: is retroactive and so the net result of 'Nature equals God' concept points up the absolute necessity of observing the rules of our species for survival and well being.” Blake's moral injunction, which is echoed throughout varying cultures (essentially “do unto others as you would like have done unto you”), reminds me of a sage I once met in North India named Faqir Chand, who was renowned for his meditative prowess and his disarming honesty and frankness. Faqir long argued that even one's own thoughts have a karmic basis and were not merely ephemeral nothings but genuinely part and parcel of the physical universe and as such follow certain unaltered laws. Blake pithily summarizes this same viewpoint when he wrote, “Every thing, even thought, is real and responds to the law of sow and reap.” Blake lived a solitary existence and some, like Doc Ball, regarded him as a loner. Though he did keep to himself, Blake felt a kinship with all life: “I found my greatest interest in swimming, surfing, and camping, traveling around, and that—it's a lonely life, that's true. But your friends are the trees and the forests and the birds and the animals, and anything that you can see, and the different people that you meet briefly. . . . every day was new.” Yet, perhaps Blake's greatest contribution to humanity was not in his surfing prowess or his heroic swimming feats, but rather in developing new products to help save people from drowning. Not only was Blake himself a lifeguard at various stages in his career but he also invented and/or developed such life saving tools as the torpedo buoy and rescue ring, besides dramatically modernizing the surfboard—from making the first hollow board to adding a fin/skeg to making a modified sailboard. Blake was indeed a man of many parts, and yet what stands out most is his humanity, his love of the ocean and what it has to offer, and the infectious enthusiasm he brought to each of his creative endeavors.  The Surfer's Way of Life“In the early days we surfed purely for pleasure and health that we derived from it.”

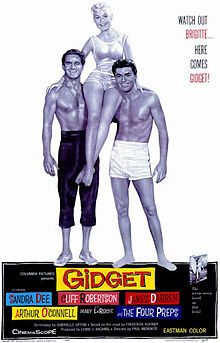

Once when I was attending an N.E.H. Conference at the University of Hawaii in the summer of 1993, one of the professors commented about how surfers tend to view the world through a different lens. I asked, “How so?” He replied, “They are more easy going and less clock conscious.” To which I responded, “Yea, but surfers are very aware of time when it comes to a freshly arrived swell.” This got me to thinking about how surfers live in general and how it evolved. While it is not accurate to claim that Tom Blake invented the surfer lifestyle (since anyone who loves riding waves must by that very love alter how they schedule their days, weeks, and months), his life is nevertheless illustrative of how a dedicated surfer prioritizes his responsibilities. It was a typical cliché in Hollywood movies about surfers that they were viewed as beach bums, who were more interested in partying than in securing a steady job. Indeed, a close analysis of the famous 1959 movie Gidget and the sappy 1964 movie, Ride the Wild Surf, reveals it to be a moral play about whether an adult male should get a steady job or simply follow the sun and surf. (See the next chapter The Big Kahuna's Dilemma and How to Live in a Darwinian Universe for a fuller explanation of this conundrum.) Blake had to break societal expectations to embark on the kind of life he chose, since the cultural mores of his time were against those who wanted to live more freely without a typical 9 to 5 job. Surfers who followed swells and not a punch clock were oftentimes regarded as Bohemians, or, worse, simply loafers who contributed nothing to society. Even in the 1970s surfers were regarded with a dismissive eye by some within more established professions. I recall once when I was taking an English course in College and the Professor lamented that surfers offered nothing good to society versus (using his somewhat questionable example) those who write poetry. I objected and raised my hand to protest, arguing that watching a surfer on a wave can be as poetic and aesthetically pleasing as anything written by Shakespeare. This response of mine didn't settle well with the Professor who protested that I was being blasphemous to (what he held to be) a sacred subject—the writer's ability to conjure magic from 26 letters. Yet, I persisted in my protest and said, “What can be more beautiful than a surfer rythmically gliding on a wave generated from thousands of miles away performing an instinctual dance that adapts to the bending contours of cascading water molecules?” But my rather amatuer attempt to use words as a weaponry defense didn't help my cause and I was summarily dismissed as a hopeless and (and I am sure to his eye, useless) beach slouch. I bring this up in a historical context because to be a surfer today is easy and is welcomed in most quarters as a wonderful and healthy activity. Surfing today has become a leisure sport enjoyed by millions. But in Tom Blake's day it was a radical departure from the norm to follow the ocean's ebb and flow and not the workaday time clock. The famed novelist and playwright, Someset Maugham, touched upon this recurring theme of living out one's chosen dream (versus what society dictates) in his famous 1944 novel, The Razor's Edge (later turned into two movies: one good, the 1946 black and white version starring Tyronne Power; and one fairly awful, the 1984 color version featuring— quite implausibly— Bill Murray in the lead role). Maugham speaks of an American who, sickened by what he witnessed during World War I as an airforce pilot, opts to go in search truth by traveling around Europe and India only to later settle down as a taxi driver back in the United States. When I saw the 1946 film with my mother one afternoon, I remember her disparging aside about the lead character, “Oh, he is just a bum and should get a regular job.” I can well imagine Tom Blake must have suffered similar insults during his time, especially given his devotion to the ocean. Surfing, as some commentators have written before, is like an anxious mistress that needs constant attention lest one neglect what she has to offer at her most alluring and charming moments. Tom Blake saw through the educational system with its Pavloian grading system of pluses and demerits, and felt strongly that a life revolving around the sea was a deeper and richer education. In a very pregnant note addressed to “Surfriders and Swimmers” Blake provides a deep and pregnant critique of our schools: “The knowledge you get in schools and colleges is second hand. The wisdom and knowledge, you get from the sea and waves and water is [original and new and fitting]. By all means, get some of this kind of education.” As a college professor for over thirty years I quite agree with Tom Blake, since most of what we need to learn and what should learn is not taught in our universities. We have lost much by not paying deeper attention to nature in its more wild and pristine manifestations. We have become stale and complacement and, not suprisingly, less attentive and aware of how nature actually works. We have, in sum, buffered ourselves with pseudo intellectualism and have lost our more natural bearings in the exchange. Tom Blake also appears to have suffered some sort of traumatic experience when quite young which led him to live a life on his own terms and not merely mimic his more conventional minded peers. What exactly happened is unclear and one can only speculate about what transformed his outlook. Blake clearly sees the ocean as his refuge and as his guide and it was in its depths that he found his true religion, one not predicated upon prior religious authority but by direct experience. For Blake Nature is God and aligning one's lifestyle to it is the highest form of worship.  The Big Kahuna's DilemmaHow to Live in a Darwinian UniverseProfessor Andrea Diem, Ph.D. “If Darwinian evolution is true—that there is no ultimate purpose to our existence save having offspring—then we are free to live the life we choose since there is no higher authority than Nature and our relationship with it.” Editor's Note: The following essay by Dr. Andrea Diem, Professor of Philosophy, was inspired by Tom Blake's atomic theory and Charles Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection. My husband David and I have been avid surfers most of our lives and we have had a long love affair with surf movies of all types, including The Endless Summer, Beach Blanket Bingo, Point Break (the original version), and a slew of others. Ironically, we are not big fans of Big Wednesday, which though panned in its original release has enjoyed a growing cult following (including one of its most vocal champions, Quentin Tarentino). However, and this may stick in the claw of our more core wave riding friends, we love the original Gidget movie starring Sandra Dee, James Darren, and Cliff Robertson.

Interestingly, the other day as I was watching Gidget from start to finish for the umpteenth time, I was wonderstruck by the real underlying theme of the movie which wasn't about surfing at all, but about how a normal, functioning adult in American society is expected to get a regular job and get in line with others in the day to day work force. Yes, it is okay to vacation (or loaf) during the summer perhaps (within limits, of course), but a male adult must earn his own living and be self-sufficient. This is brought to dramatic effect in the movie when the Big Kahuna (Cliff Robertson) explains to Gidget (played by Sandra Dee) that he wants to be a beach bum and live off the land free from the cares of modern society. The look on Sandra Dee's face when she hears the Kahuna explain his existential philosophy on life is priceless. Gidget looks like she has encountered a deranged ghost, as if not getting a regular job was tantamount to be a Russian spy or worse! The underlying moral arc in the movie Gidget isn't so much about the rapturous joy of being in the ocean and living a bohemian lifestyle as a beachcomber, but rather that surfers (of whatever stripe) must pay their societal dues or otherwise be regarded as useless outcastes. This same motif can also be seen in the overly sappy big wave movie of 1964, Ride the Wild Surf, starring Fabian, Tab Hunter, Shelly Fabares, James Mitchum and others, where a group of competitive young men around the world vie to ride the biggest waves at Waimea Bay on the famed north shore of Oahu. Yet, just like in Gidget, the moral underpinning is that surfers are perceived as bums. In one overly melodramatic scene Steamer Lane (played by Tab Hunter) confronts his girlfriend's mother over his passion for big waves, since she believes Steamer is like her no-good husband who left home and his responsibilities to follow the surf. Tab Hunter sets her straight by showing how hard he works year long and that this opportunity to surf Waimea is only a temporary one not his lifelong career. It isn't a particularly good movie or a convincing one, and certainly not as enjoyable as Gidget which is more playful and takes itself less seriously.  Nevertheless, both movies got me thinking about philosophy and Darwin. Why? Because this life is so short (and for too many quite brutal) that it raises a fundamental question: in a universe where the presiding dictum is “eat or be eaten” how should we live, given our brief sojourn on terra firma? Richard Dawkins once insightfully pointed out that even though he believed evolution by natural selection was an unassailable fact of nature we shouldn't let such guide how we want our societies to operate. The last thing we want in our day-to-day lives is an ironclad rule of “survival of the fittest.” This brings in sharp relief the Big Kahuna's dilemma since what is wrong with being a surfer, living off the land, and avoiding the trials and tribulations of the typically overworked and underpaid American worker? In other words, given this horror show we call living, doesn't it make perfectly logical sense to live a life however we deem fit, given that no matter what we achieve we will at the end disappear from the proceedings? These thoughts got me thinking about religion and why most of us, if not all, tend to believe in all sorts of nonsense that on closer inspection appears (at least to those not involved in our own personal cult) utterly bizarre or useless. Yet, if any one of these systems, regardless of how fantastical they may be, provide us with a buffer from the onslaughts of a cruel and mindless nature, then they have survival value. We evolved to believe nonsense, since such beliefs provide us with a way to avoid looking at the ultimate abyss—death and meaninglessness.

How then shall we live when there is no objective datum by which to adjudicate our choices?

More to the point, it makes perfectly good sense to believe in nonsense provided that such allows us to get on with our lives and not succumb to premature implosion. Our brains evolved to lie to us, primarily because too much unmediated reality would overwhelm our ability to navigate the probability matrix that surrounds our day-to-day activities. This is why there are literally thousands of religions and millions of different beliefs systems—ranging from rabid sports fans to political zealots to automobile fanatics. Thus, the Big Kahuna's dilemma about whether to get a full-time job or follow the sun and surf is really our own existential dilemma since we live in a Darwinian universe of innumerable possibilities. But each of our choices (whether to put our noses to the grindstone or live like free spirits) is circumscribed by a most telling factoid: our lives are mercilessly short and we die. How then shall we live when there is no objective datum by which to adjudicate our choices? In the 21st century, particularly in those countries that enjoy relative freedom of expression, the vast majority has already made their decision and that is entertainment. Neil Postman, the acerbic media critic, suggested that Americans are prone to entertain themselves to death and Aldous Huxley echoed that same sentiment decades prior in his prophetic tome, Brave New World. And instead of lamenting these keen and astute observations (as a sign of moral degradation) perhaps we should come to grips with why such ephemeral diversions (in whatever form) are wholly reasonable and sensible in this carnivore arena where no one gets out unscathed. Provided that another person's enjoyment doesn't infringe on our own (and we allow others the fuller trajectories of their own short lifespan without unnecessary injury), then a powerful argument can be made for believing anything we so desire, since such believing can and does allow many of us to better navigate the ups and downs of this unremitting game of differential reproductive winners and losers. This is why religion persists, even if we may think almost all of it is completely ridiculous and capricious because it provides a value system (even if fictional in origin) for the devotee that cushions him or her from the endless onslaughts of existence. Any schema that can ward off angst, dread, and suicidal tendencies, is welcome and will be passed on to future generations, even if such models are entirely imaginary creations. Technology has become the world's newest and fastest growing religion, if we accept Paul Tillich's definition of such as “ultimate concern.” The horror that Gidget feels about Kahuna not getting a job is in essence really a conflict over how to best live this life. What she fails to realize, of course, is that there is no “best” way to live since there are no absolute guidelines, save the ones that we indoctrinate ourselves with. Today, vast numbers of us (but more specifically the younger generation) have opted to spend hours each day interacting with increasingly sophisticated technology. We have immersed ourselves in virtual worlds, whether it obsessively tapping and swiping away at our smart phones, or donning headsets to correspond with others in simulated warfare games, or developing avatar like characters in cyber world correspondences. Technology has become the world's newest and fastest growing religion, if we accept Paul Tillich's definition of such as “ultimate concern.” While many find our love affair with all things computational to be depressing or a sign of degeneracy, such love is nothing new given that we have always been fascinated with augmenting ourselves with a variety of materials. The difference now is that our electronic devices have become ubiquitous and progressively more powerful and cheaper. The church of technology isn't miles away but at our fingertips and with cloud computing it tracks our every movement. Today's Internet is similar to an ocean full of waves, providing innumerable options. So much so, that the Big Kahuna of today is confronted with a new kind of predicament: whether to randomly surf the Net without any end goal or buckle down and find a real paying job doing something constructive in the cyber world. Looking over at my fifteen year son, Shaun, playing away on his three monitors all sorts of interactive games (with no truly higher purpose in mind, save savoring the ups and downs of the battle), I see the Kahuna's dilemma anew. Will our total digital immersion be likened to a 1950s beach bum who would rather surf than get a “real” job? Would Sandra Dee looks just as horrified as she did when seeing the beatnik ways of Cliff Robertson? The Big Kahuna's dilemma is ours and whatever choices we make, we may in turn reflect what Soren Kierkegaard opined nearly two centuries ago: “I see it all perfectly; there are two possible situations—one can either do this or that. My honest opinion and my friendly advice is this: do it or do not do it—you will regret both.”

“Finally, when my youth was left far behind and the meaning of philosophy, science, and life had been studied, I was able to reconcile Christ's eternal life concept with Einstein's mass energy equivalence theory.”

TOM BLAKE'S ACCOMPLISHMENTSExcerpted from legendarysurfers.com1922 - set the world swimming record in the ten mile open. 1926 - first person to surf Malibu, along with Sam Reid. 1926 - invented the hollow surfboard. 1928 - won the first Pacific Coast Surfriding Championship. 1928 - invented the hollow paddleboard. 1929 - invented the waterproof camera housing. 1931 - invented the sailboard. 1931 - patented & manufactured the first production surfboard. 1932 - won the Catalina Paddleboard Race. 1935 - invented the surfboard fin, a.k.a. skeg, or keel. 1935 - published the first book solely devoted to surfing, Hawaiian Surfboard. 1937 - produced & patented the first torpedo buoy and rescue ring, both made of "dua-aluminum" 1940s - first production sailboards. Leader in physical fitness, natural foods and healthy diet. Virtually began the surfing lifestyle, as we know it. FOR FURTHER INFORMATIONThe most valuable resource (and why this small book is even possible) is Gary Lynch's magisterial, Tom Blake: The Uncommon Journey of a Pioneer Waterman (Croul Publishers, 2001). This truly remarkable biography is a treasure trove of materials (replete with rare photographs, letters, and ephemera) about Tom Blake's philosophy, personal life, and surfing accomplishments. There are several resources online but each of them, with some exceptions, utilizes parts from Gary Lynch's work. For a deeper and rawer look into Blake's legacy I recommend the Tom Blake Scrapbook that is available in a beautiful edition from Croul Publishers in Newport Beach. We have also produced two short movies about Tom Blake that are online via the YouTube channel, Neuralsurfer Vision. These are “Tom Blake: The Original Neural Surfer” and “Voice of the Atom: Tom Blake's Natural Philosophy.” “There is no sentiment in Nature, but there [is] plenty of necessity.” |