|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992). David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992).SEE MORE ESSAYS WRITTEN BY DAVID LANE WHY I MEDITATEReflections of a Neural SurferDavid Lane

Therefore I cannot say that I meditate for a singular reason, though simple enjoyment remains a mainstay.

Recently there was an intense discussion on spiritual matters on Brian Hines� widely read blog, The Church of the Churchless, and an Indian gentleman wrote to me via email providing a link to it, primarily because there was a question about why I still meditate given my skeptical outlook on most things religious. He too was curious and wanted to know more about my daily practice and my reasoning behind it. The following is my response. Everyone I know who is brought up in a strict Catholic tradition (going to Church, attending parochial schools, receiving communion and confirmation) is deeply infected by its theological ideas, even if later they contravene them in varying ways. I say this precisely because from a very early age I suffered from a severe longing for something transcendent, what in German is known as sehnsucht, properly defined as “thoughts and feelings about all facets of life that are unfinished or imperfect, paired with a yearning for ideal alternative experiences. It has been referred to as ‘life�s longings’; or an individual’s search for happiness while coping with the reality of unattainable wishes.”  I suspect that almost all human beings have at one time or another felt a sense of longing that couldn’t be resolved by what the world has on offer. In any case, I remember very early on feeling a profound absence, even though I was surrounded by three loving siblings and a coterie of good childhood friends. The problem with Catholicism was that it didn’t offer me an experiential solution to my difficulties, but on the whole only exacerbated it with its overriding emphasis on sin, suffering, and ritualism, not to mention an unbending dogmatism concerning unknowable mysteries such as the resurrection of Christ and the virginity of his mother. Thus it is not surprising that I was open to alternative views while still very young. Reflecting back now I can vividly recall first practicing yoga when I was 10 years old. I was undoubtedly a product of my age or perhaps of what was on television, since I was mesmerized by Richard Hittleman’s popular show, Yoga for Health, which reportedly debuted on local television in Los Angeles, California in 1961. I used to visit weekly the North Hollywood public library that had a few books on yoga and from those few rudimentary texts I started practicing pranayama (breath control), asanas (body postures), and mudras (hand positions). In the midst of these self-taught exercises, I happened to watch the Les Crane television show with my mother. I think it was in the afternoon and Mr. Crane was interviewing Maharishi Mahesh Yogi for nearly an hour and my mom and I were deeply moved by it. I particularly liked the guru’s emphasis on stilling the mind. I mention this because although I was not personally drawn to the Maharishi, the idea of meditation struck a cord with me.

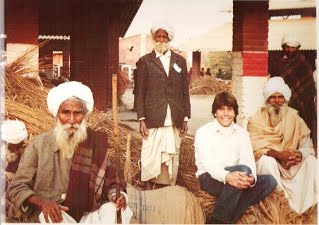

At this tender age of eleven years old I also chanced upon Paramahansa Yogananda’s famous book, Autobiography of a Yogi. I was enthralled with it and couldn’t put the book down, reading it very carefully each day. I think this particular book must have been the tipping point, as it has been a touchstone for many people worldwide (including Steve Jobs who allegedly had it on his own personal iPad and re-read it yearly). Yogananda’s tale is a fantastic one and not always a believable one. But being indoctrinated within Catholicism and its innumerable miraculous stories concerning saints and the like, I was overly ripe for the offering. I coupled my Indian philosophical reading with biographies of Catholic saints and mystics. I was particularly enamored with St. John Bosco who had visions of the Virgin Mary. In one story (which I now think must be part of some questionable hagiographical rendition) St. John Bosco went to Church and offered his lunch (or was it an apple?) to a statue of the Virgin Mary and it came alive and took it. For some strange reason, this appealed to me and I used go to our St. Charles Church (which also housed the elementary school I attended) and very intently offered my lunch to the statue of the Virgin Mary. When that didn’t work, I tried offering it to the statute of St. Joseph. Again to no avail. Thankfully, this miracle seeking on my part was short-lived and I dived more deeply into my yogic studies and practice. I also branched out and started reading about the life of Buddha. One night I was so taken by Siddhartha’s firm resolution to sit under the Bodhi Tree until he reached enlightenment that I got out of bed (it was a school night, of course) and I crossed my legs and sat on the floor and vowed not to get up until I too received illumination. Of course, given my monkey mind, I think it took all of but ten minutes for me to contemplate getting some cereal and watching some television instead. Although I was quite athletically inclined, in 6th grade I started hanging out with a different group of friends who were experimenting with drugs. We started taking these small white pills during recess called “Bennies” which I later learned was a street term for Benzedrine which was a “racemic mixture of amphetamine” and which got me and my comrades super energetic. At recess I would pop one or two so I could play pick-up basketball better, particularly when trying to beat my good friend Ed Grady for his hot lunch, which his mother invariably brought to him each day around noon. Then one night while I was staying with another friend [redacted for his protection] at his home in the hills of Studio City his brother had us smoke some pot he had with him. I didn’t get high that night, since I was suffering from a Clintonesque moment whereby I couldn’t seem to inhale the smoke long enough to get a buzz. A few days later I got the hang of it and got quite intoxicated. So high, in fact, that during this very first trip everything turned unexpectedly psychedelic. I felt I was exported into a different world, quite parallel to the one I knew and it was exceptionally frightening. Time stood still and all the people around me shrunk down as if cued by an accordion into midgets. This experience lasted for hours and I was quite distraught. Later I learned that the pot had been laced with opium. The peer pressure was such (or, more accurately, my perception of it) that I continued for nearly six or seven months experimenting with pot, Bennies, and occasionally some strong hashish, usually laced with opium. My experiences, outside of the ones with Bennies (which were non-hallucinogenic) were invariably anxiety inducing and never very pleasant. I had one particularly hellish experience when I smoked some hashish (again laced with opium) in 7th grade right before school started. I was sitting in class and everything swirled around me as if I had entered a time portal where everyone kept shrinking in size and moments would seem to last for an eternity. I wanted to go to the school nurse and tell her about it to get some help, but I knew that if I did I would get kicked out and my mom and dad would never forgive me. So I hung on and it took days for me to drop down to a relatively normal state of consciousness. Shortly thereafter at the end of my 7th grade term I stopped cold turkey and didn’t take any more drugs, not even in high school or college or graduate school. I was, as the clich�’ goes, “scared straight.” Yet, these experiences—preliminary and as immature as they were—only intensified an abiding loneliness in me and pushed me further to find some transcendent solution to my existential dilemma. I became an obsessive reader of all things Eastern. At the age of 15 I had a remarkable experience of speaking in tongues when I attended a charismatic mass at Loyola University near Manhattan Beach that convinced me that higher states of consciousness were possible without ingesting drugs. As my quest intensified, I eventually turned vegetarian at the age of 16 and consciously looked for a spiritual guide who could instruct me further on the inner journey. Although I met a number of teachers, including the infamous Father Yod and Yogi Bhajan among others, I developed a peculiar standard with which to appraise any potential master. I ruminated to myself that he must be a vegetarian and follow a path of ahimsa or non-violence. He must not charge any money whatsoever for instruction and not make any absolute claims about his own inner attainment. And, finally (and I am fairly sure that the Sikh influence here, though not conscious, was operative), the teacher should have an uncut hair and beard. To be sure, this very guru template was influenced by what I was reading and what I was experiencing and says much about how persuasively our own cultural upbringing flavors our inner sojourns, contrary to what we may mistakenly believe to be a pure and virginal quest for the Absolute.  circa 1983, Beas, Punjab, India] After years of seeking, I came upon my eventual teacher, Charan Singh of Radhasoami Satsang Beas, when I was 17 years old. The story behind this is a long and intimate one that is best left retold at another time. I will simply say that it forever changed my outlook and made me focus my efforts in a quite specific way. Before learning of Charan Singh and his meditational method, I had practiced Kundalini yoga for a year and was partial to the philosophical outlook of Ramana Maharshi and Advaita Vedanta. Charan Singh, who traced his lineage from his grandfather and guru, Sawan Singh, back to Jaimal Singh and Shiv Dayal Singh and earlier versions of Sant Mat, taught a streamlined version of surat shabd yoga. It offered a three-fold method of concentration which included repeating a five-word mantra, to focusing one’s attention and sight on inner light, and listening to a hidden sound or melody within. This latter aspect (sound current or shabd), from which the practice derives its distinctive name, seemed odd to me when I first learned about it. Given my predilection for jnana yoga, as espoused by Ramana Maharshi (specifically his most well known book, Talks With Sri Ramana Maharshi), I thought the idea of listening to some inner music to become enlightened sounded (and the pun here is not intentional) silly at best. But I was so enamored by Charan Singh and how he conducted himself that I had no hesitation in practicing such a technique. Although Charan Singh wouldn’t initiate me right away, even though I pleaded my case each month off and on for years (he made me wait five years until I was 22 years of age), I started doing shabd yoga from what I learned from certain Radhasoami books. Almost immediately I saw how effective it was and became convinced it was a viable way to still the mind and explore the end source of one’s own consciousness. There is much I can write about my eventual tutelage under Charan Singh and my many travels to India where I met with a large number of shabd yoga masters and the like, including most impressively my deep and abiding connection with Baba Faqir Chand, but I wish to narrow the focus now to the question underlying the purpose of this essay: why do I meditate? And, additionally, why do I practice shabd yoga and not some other pathway? There are many answers to that query and I will try to elucidate some of them. But perhaps the best response (and one which echoes Alan Watts’ own sentiment on the matter) is the simplest one. I enjoy it. I like sitting quietly for long periods of time (anywhere from 2 to 4 hours) daily and resting in my own being without being distracted by an outside world that consistently clamors for my divided attention. There is something innately blissful in reposing within one‘s self and experiencing the quietude of one’s own mind undoing its ceaseless machinations. There are I would imagine moments in everyone’s life (even if fleeting) where one fully awakens to the present moment and the overwhelming wonder of it all and feels a communion with all that arises. I remember once when I was surfing for nearly 8 straight hours at Cojo at the Bixby Ranch below Point Conception and the waves were so good that I couldn’t leave the water even though I was thirsty and hungry. I was drunk on Neptune energy, so much so that when I finally reached the shore just after sunset I couldn’t move and sat on the sand supremely content and serene and felt like I was going to melt with all that I could see, hear, touch, feel, and smell. This state of ecstasy felt timeless, despite only lasting some 10 or so minutes until hyperthermia and exhaustion overtook over my chilling body.

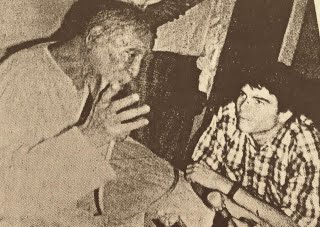

I bring this up because meditation for me is akin to why I surf. I have surfed almost my entire life and I derive the same happy giddiness from it now than I did when I was 10 years old and riding inflatable rafts with my long-time friend Pat Donahue at Sorrento Grill in Santa Monica, California. Why? Because whenever I am in the water I have to be totally present to what is happening, whether it is an incoming rogue wave, a sweeping riptide, a school of curious dolphins, a stray seal, stealthy sting rays, or the joy of being inside a vacuuming tube collapsing all around my hydro foiling body. The writer for the New Yorker William Finnegan in his meandering but engaging book Barbarian Days captured this feeling well when in a recent article published in The Concourse he recalls how Kelly Slater, the most celebrated surfer in the modern era, remarked when asked by an interviewer how he felt after winning another world title and a hundred thousand dollars at Pipeline in Hawaii exclaimed, “I’d give it back to have another half-hour with two guys out there.” To which Finnegan commented, “He’s dead serious.” Happiness, in one insightful definition, is when we are awake to a present moment that we want to fully be in. The glitch, of course, is that there are far too many times in which we don’t want to be there, where we reflect more about our past or fantasize about some future possibility. Meditation is quite simply allowing consciousness to be present and allowing it to envelop upon itself. I have noticed that continued practice is a privilege and not a discipline, even though at first it may appear like that. I think Gerald Edelman, the distinguished Nobel Prize winner and controversial pioneer in consciousness studies, captures the essence of why meditation works by his two-fold understanding of awareness. Human beings, unlike almost all other animals, are too often trapped with their own dissociative states and as such are caught within a web of virtual simulations. While this 2nd nature capacity evolved as a great advantage to Homo Sapiens (“simulating before acting” is advantageous in a Hunger Game like world, just as in-sourcing outcomes before out-sourcing them in a real world tends to keep one alive), it also comes with a very heavy price: we are prone to imprison ourselves in virtual reflections and projections and not witness how these manifestations arise from our own consciousness as such.  The late Baba Faqir Chand and David Lane, India, 1978 Meditation is a process to trace the source from which all such manifestations arise, similar to being in an ocean and understanding how and why waves arise upon its surface without forgetting that they too are part and parcel of the sea. We are, lest we forget, part of all that arises and diving deep into that ocean of being allows a never-ending journey into the mystery of what it is to be alive and conscious. As for myself, I have noticed that shabd yoga practice is a very practical method of focusing the mind back to its source. It does this by giving one’s attention a three-fold excuse to sit quietly and not wander outside. First, by repeating a word or words over and over again it acts as a sort of neurological koan, paradoxically restraining the rational mind from generating narrative sequences; second, by contemplating at one point or center and being attentive to whatever arises (light, darkness, forms) but not being anxious about such calms one’s entire nervous system to such a degree that the body literally starts to enjoy its own energy without having to expend it needlessly; and third, listening to an apparently unbreakable radiance or melody enlivens one within an unexplored realm. I don’t meditate with an end-goal or with some underlying desire for a specific enlightened state mentioned in some ancient holy book or postulated by a revered sage. I meditate just like I surf: for the bliss of the ride. Where it will eventually take me is not dissimilar to where life takes us: to the unexpected and to the unexplored. In other words, it is the means of meditation and not some desired end that is fulfilling. I have noticed that if I get anxious about some result or when I feel a rush as if entering a time and space portal to a new world, I lose my own balance by clutching. Letting go, surrendering, to our own consciousness and not succumbing to the endless stream of virtual simulations (which our brains are evolutionary designed to do) is to apprehend the meta program and experience why it emerged.

Harjit Singh Sandhu in his Foreword to Baba Faqir Chand’s brilliant book, Jeevan Mukti, explains the process of surat shabd yoga meditation well when he writes, “In meditation, Light and Sound are natural manifestations of the Self. Maharaj [Faqir Chand] warns us not to stop or get entangled in inner phenomena [the virtual simulator?]. Instead he guides us to direct our attention to the silent observer or witness of Light and Sound. In this manner, one is liberated from all manifestations—physical, mental and spiritual and what remains is beyond description. It is what it is.” Far too often meditation practice gets intertwined with a specific path or theological doctrine, such that it becomes a pathway to benefit the outward religion or guru since the disciple mistakenly believes that without either he or she could not uncover the mystery of their own being. This is why Ramana Maharshi’s quote concerning ultimate realization is so liberating when he writes, “It is false to speak of realisation. What is there to realise? The real is as it is always. We are not creating anything new or achieving something which we did not have before. The illustration given in books is this. We dig a well and create a huge pit. The space in the pit or well has not been created by us. We have just removed the earth which was filling the space there. The space was there then and is also there now. Similarly we have simply to throw out all the age-long samskaras [innate tendencies] which are inside us. When all of them have been given up, the Self will shine alone.” It should also be admitted, however, that meditation can also serve as a scientific expedition, not dissimilar to how one might climb Mount Everest for the first time or voyage to an uncharted island in the Pacific. For instance, shabd yoga claims that it can essentially induce a conscious near-death experience and provide one with a glimpse of what it is like to leave one’s body and enter into ever-increasing lucid states of awareness. This is a bold claim and one that needs verification, even if the would-be meditator may ultimately arrive at a different interpretation of why such experiences arise. However, for such a hypothesis to be tested one does need to actually engage in the practice and at least observe such inward phenomena. It is too easy to dismiss the mystical with cheap reductionism, such as “it is all brain hallucinations” especially when even our own waking state is itself the product of a complex neuronal symphony. Hence, there is a pioneering aspect to meditation that can, at times, be quite exhilarating. In a letter to one of his disciples, Jagat Singh, a well regarded Master within the Radhasoami Beas tradition, both commends and slightly reprimands him about his experiences when he explains, “The experience you had during the so-called Bhajanless days, that is, brilliant light surrounded by twinkling lights, was real and correct and was due to your attention being subconsciously at the eye center. It was perfectly natural for the attention to be riveted on the central white light as also the suction. The nearer you draw to this light, the greater will be the suction, for you have to pierce and cross it. You did miss something there, for you should NOT [my emphasis] have battled against this suction. You should have remained relaxed and allowed yourself to be drawn up. . . .” Jagat Singh’s advice is a procedural one and offers a tantalizing clue about how to proceed when in such an exalted state of awareness. This reminds of when I was looking for surf on the backside of Catalina island on my boat and I would ask residents their advice about when and where to find good waves. I listened to one seasoned surf veteran who advised me to proceed from Cat harbor and venture south, being sure to look at two well known spots first (Shark Harbor and Ben Weston beach). But he then dangled a tantalizing proposition about an outer reef just off Salta Verde that seldom breaks but is epic when it does. While I could sit on the back of my boat and armchair dream about such possibilities, I realized that I had to actually motor out there and take a look to confirm what I had been told. Meditation as an expedition is not different in that regard. This naturally doesn’t mean that what we experience will invariably be characterized exactly how others have done so before, but it does provide us with the necessary background to make our own adjudications (rightly or wrongly). I have now meditated for nearly 50 years with the past five years being my most intensive. On the exploratory front (and given my deep interest in consciousness studies), I think the budding field of neuroscience can greatly benefit by taking up the practice since it provides rich interior detail to what can happen to the brain under concentrative circumstances. As for myself, I have gained a much greater appreciation of how and why the brain constantly simulates an almost endless stream of end game scenarios. 2nd nature consciousness is a virtual simulator par excellence and because of its prodigious output we invariably get ensnared within its balloon like worlds. If by deep meditation we can stand apart from such enveloping excursions, we can witness a profound undoing and in the process experience hitherto hidden realms of being. Therefore I cannot say that I meditate for a singular reason, though simple enjoyment remains a mainstay, just as I don’t surf with one purpose in mind. If consciousness can be likened to an ocean of possibilities, then it seems wise to want to explore the depths of that realm as well as it surface topography.

Meditation is a present [yes, the pun is intended], since in the Darwinian struggle of existence it is rare for Homo sapiens to have freedom from the day-to-day demands of making a living. Just as being bored is a privilege only accorded to those who have sufficient time and resources not to be obligated by overwhelming individual or social needs. To be able to sit still for a set duration of time and not be distracted by outer wants and needs is a precious opportunity. I find myself lucky to be able to indulge in such a wondrous adventure. What it will ultimately lead to I cannot predict. But I do know that like surfing it is a process that is rewarding in itself, even if I wipeout on occasion or get skunked by a lack of swell or an impenetrable fog bank. Jagat Singh perhaps said it best about meditation when he opined, “Let things happen as they do naturally. You cannot hustle the power within.” Or, as Ramana pithily argued, “There is no greater mystery than this, that we keep seeking reality though in fact we are reality. We think that there is something hiding reality and that this must be destroyed before reality is gained. How ridiculous! A day will dawn when you will laugh at all your past efforts. That which will be the day you laugh is also here and now.”

|