|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992). David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992).SEE MORE ESSAYS WRITTEN BY DAVID LANE The JourneyA Voyage of Light and SoundDavid Lane

Instead of resorting to quick and premature conclusions, so as to resolve an emotional religious debate, what is needed is a suspension of belief.

In this article we will focus our study on the surat shabd yoga tradition of India, which, due to its clearly elaborated process and technique, offers a viable method for those interested in understanding and correlating mystical insights. Such a phenomenological analysis will hopefully enable us to nurture the seeds for a transpersonal science, one that meets the necessary requirements of a genuine scientific enterprise. As Ken Wilber (1983a) points out: "1. Instrumental injunction. This is always of the form, 'If you want to know this, do this.' 2. Intuitive apprehension. This is a cognitive grasp, prehension, or immediate experience of the object domain (or aspect of the object domain) addressed by the injunction; that is, the immediate data-apprehension. 3. Communal confirmation. This is a checking of results (apprehensions or data) with others who have adequately completed the injunctive and apprehensive strands."

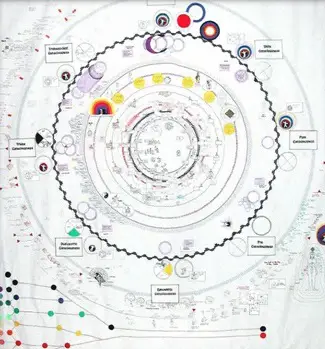

Our examination, based largely upon the writings of the Radhasoami masters (including Shiv Dayal Singh, Sawan Singh, Baba Faqir Chand, et al.) and modern non- dual/monistic thinkers (Ramana Maharshi, Da Free John, and Ken Wilber) will as unfold as follows: A) A brief outline of surat shabd yoga tradition and practice, especially in relation to other spiritual traditions, e.g., kundalini yoga. B) A phenomenological description of how the surat (soul/attention) leaves the physical body during meditation and commences an inner voyage of light and sound through vast regions of existence. C) A summation of how surat shabd yoga can serve as a model methodology for firsthand encounters with spiritual realities, marking a safe and definitive program for future trans-empirical excursions. Overall, my thesis is that this type of undertaking, allowing for a deeper grasp of mystical dimensions, will help promote further studies in consciously induced near-death experiences which have a rigorous experiential and testable basis. Unlike other yogic disciplines in India, such as kundalini, surat shabd yoga does not advocate breath control (pranayama) or a series of physical postures (asanas/mudras) as part of its practice. Rather, it is concerned with withdrawing consciousness from the nine apertures of the body (eyes, ears, nose, mouth, genitals, and alimentary canal) and transcending the corporeal frame and its limitations altogether. This is accomplished by attaching the mind's attention to an inner light and sound which is believed to be radiating behind the proverbial "tenth door" (the "third eye" of the Hindus), anatomically located behind and slightly above the physical eyes (Shiv Dayal Singh, 1970). When consciousness becomes totally concentrated at this pivotal point "between the worlds," the soul, according to the saints in this tradition, leaves the body and experiences in elevating degrees higher regions of bliss. The distinctive characteristic of surat shabd yoga is its emphasis on listening to the inner sound current, known variously as shabd, nad, or audible life stream. It is through this union of the soul with the primordial music of the universe that the practice derives its name (surat--soul, shabd--sound current; yoga--union). To be able to achieve a consciously induced near-death state takes great effort. Hence, masters of this path emphasize a three- fold method designed to still the mind and vacate the body: simran, dhyan, and bhajan (Charan Singh, 1979). Simran, the repetition of a holy name or names, draws one's attention to the eye center, keeping thoughts from being scattered too far outside. Such sacred remembrance is similar in form to the use of a mantra or special prayer, except that the name(s) are repeated silently with the mind and not with the tongue. This stage, according to practitioners, is the first and perhaps most difficult leg of meditation. Dhyan, contemplation within, is a technical procedure to hold one's attention at the third eye focus. In the beginning this may be simply gazing into the darkness or re-imaging the guru's face, etc., but it eventually develops into seeing light of various shapes. Out of this light appears the "radiant form" of one's spiritual master, who guides the neophyte on the inner voyage and becomes the central point of dhyan.

Bhajan, listening to the celestial melody or sound, is the last and most important part of surat shabd yoga, because it is the vehicle by which the meditator can travel to exalted planes of awareness. Whereas simran draws and dhyan holds the mind's attention, it is bhajan that takes awareness on its upward ascent back to the Supreme Abode, Sach Khand. Naturally, mastery of surat shabd yoga is not an overnight affair, but involves years of consistent application and struggle. The desired results, adepts in the tradition agree, being largely due to the earnestness and day-to-day practice of the seeker. THE INNER ASCENTIn due time, if the process is complete, the individual spirit current or substance is slowly withdrawn from the body. First from the lower extremities which become feelingless, and then from the rest of the body. The process is identical with that which takes place at the time of death, only this is voluntary, while that of death is involuntary. Eventually, he is able to pierce the veil that intervenes--which in reality is "not thicker than the wing of a butterfly"--and then he opens what is called the "Tenth Door" and steps out into a new world. The body remains in the position in which he left it, quite senseless, but unharmed by the process. He is now in a world he never saw before.... --(Julian P. Johnson, 1952) Before the inner voyage of light and sound can begin, the meditator must become adept at withdrawing his/her attention from the world and concentrating one pointedly at the third eye center. Accordingly, when the neophyte has achieved even a modicum of success, having sensations of numbness just up to the solar plexus, flashes of light will begin to manifest. At first it appears that the light is coming and going, causing the phenomenon of bright sparks, but in actuality it is the mind which is ascending and descending (Charan Singh, 1958, 1967, 1973, 1979). The feeling of physical insensibility is one of the important "acid tests" to determine if the mediation process is proceeding correctly. Starting in the feet, numbness rises slowly through the lower extremities, until the entire body feels like stone. When such a voluntary paralysis occurs, the meditator gravitates more to the inner universe than to the outer one. According to the masters (Julian P. Johnson, 1974), it is the function of simran to instigate this type of benumbing impression, which releases the mind from its constructing hold on the material corpus. It is at this junction when the meditator senses an intense feeling of upward movement, as if being literally pulled by a magnetic force. This sucking effect is the direct result of one's attention moving inward away from the outer orifices. Though it but a preliminary stage, the student experiences first-hand what it is like to have an out-of-body sensation. With practice, the meditator finally does achieve total out-of-body consciousness, traveling at immense speeds through regions of darkness, not dissimilar in content to reports of clinically dead patients who have been resuscitated (Raymond Moody, 1975, Kenneth Ring, 1980, Darshan Singh, 1982).

After complete withdrawal from the physical body, the neophyte's capacity for inner sight (nirat) and sound (surat) increases tremendously, enabling him/her to see and hear clearly what was only thought before to be a figment of religious imagination. Accompanying this ability is also the realization of a super-conscious state of awareness, remarkably more vivid and lucid than the ordinary waking state (Sawan Singh, 1974). To understand how such a new degree of consciousness can be awakened, it is important to see how awareness moves through various degrees of clarity. In the waking state, for instance, attention is centered behind the eyes at the back of the head. But, after eighteen or so hours, we notice a movement downward and inward from this station towards the throat (Jagat Singh, 1972) culminating in sleep. Likewise, after about eight hours, we sense a rising upwards to the eyes, with the final termination being, of course, our normal, everyday consciousness. In both of these cases, our common language expresses in a graphically simple way the process of awareness: "We fall asleep; we wake up," "My eyes are heavy;" "I feel so awake and high." In yoga psychology the farther down one's consciousness descends the deeper the sleep (or unconscious) state; the further up it ascends the higher the awareness (super-conscious). The pattern is quite clear; clarity increases steadily the more one ascends (not vice versa). Ken Wilber (1979, 1981) has beautifully described this spectrum of consciousness as having a definite hierarchical structure, with the higher orders subsuming and transcending their lower counterparts. The following account, primarily based upon Shiv Dayal Singh's Hidayatnama is filled with rich mythological characterizations, metaphors, and illustrations. For anyone steeped in science, the account will sound too fantastic to be true. However, we should keep in mind that although Shiv Dayal Singh's description may be limited to the analogies of the 19th century, his fundamental insights are consistent with mystics from time immemorial. When reading Shiv Dayal Singh's descriptions of the inner regions we should always keep in mind that trans-rational experiences cannot be adequately contained by the inherent boundaries of human language. Let us not confuse a map for the real territory or a menu for the meal. THE FIRST REGION: Sahas-dal-kanwal “thousand petalled lotus"When your eye turns inwards in the brain and you see the firmament within, and your spirit leaves the body and rises upwards, you will see the Akash in which is located Sahas-dal-kanwal, the thousand petals of which perform the various functions pertaining to the three worlds. Its effulgence will exhilarate your spirit. You will at that stage, witness Niranjan, the lord of three worlds. Several religions which attained this stage and took the deity thereof to be the lord of all, were duped. Seeing the light and refulgence of this region they felt satiated. Their upward progress was stopped. They did not find the guide to higher regions. Hence they could not proceed further. --Shiv Dayal Singh, Hidayatnama Although the wondrous journey out of the body in surat shabd yoga meditation begins in darkness, eventually the meditator glimpses keen points of light, much like stars filling up a black midnight sky. The student is advised to focus his/her attention on the largest and brightest of these "stars" (Kirpal Singh, 1974, 1975, 1976), which with repeated concentration will burst revealing a radiance similar to that of a sun (Sawan Singh, 1970, 1974). When this light explodes, a brilliance comparable to a full moon will pull one's attention even further within. Out of that light, according to the masters (Julian P. Johnson, 1953), known as Asht-dal-kanwal ("Eight petal lotus"), the resplendent form of one's guru will appear. This marks the half-way point in the disciple's ascent, since from here on one is guided to the upper regions by the radiant form of the master (Sawan Singh, 1974). Hence it is by comparison an easier progression for the soul than the withdrawal of the mind current from the body. Along with the seeing of light, consisting of different colors and hues due partly to a particular person's karma (Faqir Chand, 1978), the meditator also hears a variety of different sounds. At first, as the concentration becomes finer it will assume a more distinct tone, not dissimilar to the tinkling of bells. Indeed, it is the bell sound which is to be held onto, as its melody will help lead the soul into the first region, known technically in Radhasoami as Sahas-dal-kanwal, but also termed in other traditions as the astral plane, turiya pad, etc. (Swami Muktananda, 1974).

Entrance into the pure astral plane, though heralded as a magnificent achievement, is, according to Sant Mat, but the beginning of the inner voyage. It is alleged by many saints in the tradition (Kabir, Tulsi Sahib, Sawan Singh, etc.) that several great religious leaders mistakenly believed that the light and sound of this region were of the Absolute Lord. Instead of realizing that the manifestations were partial glimpses of a higher reality, they worshipped them as the totality of God. This kind of error is perhaps the chief reason why the Sant Mat and Radhasoami movements stress so much the necessity of a living guide (Charan Singh, 1974). Above all else, the masters emphasize, test thoroughly whatever appears inside meditation. [The main test advised by the mystics is to repeat slowly the holy name or names which were given at the time of initiation; also verify the authenticity of one's experiences with the outer guru for his/her validation.] Each major region of consciousness has its own center and guiding lord. In Sahas-dal-kanwal the ruler is known as the lord of light and is the creator of all the universe in its jurisdiction (Julian P. Johnson, 1974). However, the extent of each ruler's power is limited and circumscribed by the next higher deity, who, likewise receives its creative energy from above, etc. This governing hierarchy, like the kundalini chakra system, is based on the concept that all spiritual evolution (and even material transformation) was preceded by an involution (Charan Singh, 1973). Therefore, the meditator must pass through several regions of light and sound before attaining true enlightenment. In order to overcome the many barriers and obstacles on the way, the guru instructs the student not to attach him or her self to any particular vision, as they are merely signposts along the way (Charan Singh, 1979; Faqir Chand, 1976). In fact, all of the intermediary lords, or centers of power, are not to be venerated but transcended. It is for this reason that the Beas branch of the Radhasoamis and Sawan-Kirpal Mission in agreement with previous saints, give out five holy names as their meditation mantra. Each name represents the presiding lord and his relative spiritual energy; to the meditator they serve as passwords, so to say, to insure safe passage into the next level of consciousness (Charan Singh, 1973). Obviously, the concern here is that a student may get stuck or retained in one of the lower realms, believing that he/she has reached the ultimate, when, in fact, what they have attained is illusory and impermanent. Surat shabd yoga literature is replete with stories of would-be masters who have been duped on the inner journey (for instance, see the book Anurag Sagar which goes on in detail about sages being misled in their meditations). THE SECOND REGION: Prikuti "three prominences"At the apex of this Akash (in Sahas-dal-kanwal), there is a passage which is very small like the eye of a needle. Your Surat (spirit) should penetrate this eye. Further on, there is Bank nal, the crooked path, which goes straight and then downwards and again upwards. Beyond this passage comes the second stage. Trikuti (having three prominences) is situated here. It is one lakh yojan in length and one lakh yojan in width [millions of miles in inner space; an expression describing tremendous dimensions]. There are numerous varieties of glories and spectacles at that plane which are difficult to describe. Thousands of suns and moons look pale in comparison to the light there. All the time, melodious sounds of Ong Ong and Hoo Hoo, and sounds resembling thunder of clouds, reverberate there. Progression to successively higher regions of existence is secured in Radhasoami and Sant Mat through listening to the finer shabd (sound) melodies. As remarked before, it is the bell sound which leads the soul into the first region. Subsequently, access to the next stage, Trikuti, is garnered by attaching one's attention to the powerful rhythm of drums (or, clashing thunder). However, on the sojourn between the first and second regions, one must pass through bank nal, a crooked tunnel which can ward off spirits from progressing further. An interesting description of this particular stage comes from a letter written by a disciple of Sawan Singh, dated January 30, 1945 (Rai Sahib Munshi Ram, 1974): My progress again started from 9th January. Sometimes I could see light and get some taste, but there was not upward progress. One day I saw three paths and after many days my soul started following the middle one. It is not a straight path but a sort of crooked tunnel which goes on narrowing as one moves forward. At one place it was so narrow that I had to crawl forward on my stomach. There were many snakes and scorpions in this path but through Your mercy they all appeared dead and did no harm to me. I felt absolutely no fear because I was conscious all the time of your presence and your Shabd Form. Further on, the path narrowed still more and a sinner like myself could never go through it without Your mercy and grace. It is like a round tunnel and it is all lightened up with a beautiful circular light like that of the morning sun. It appears as if the sun is rising. I tried to pass through this sun but could not do so and therefore came back through this tunnel. This happened about two or three days ago. Trikuti, so named because of the three huge mountains of light situated there, is the home of the universal mind where individual karmas have their origin. Saints point out that this region is the most difficult to traverse because it means surrendering one's mind entirely. Since such a task is almost impossible immediately, the soul stays within the boundaries of the second stage for a considerable duration. The spectacles of Trikuti are reported to be so enticing and spectacular that the meditator often does not want to go on further. Indeed, the inner master sometimes prevents the student from beholding the sights in fear that he/she will become too saturated with joy and forget his/her real mission (Rai Sahib Munshi Ram, 1974). Faqir Chand, a radical teacher in the Radhasoami movement who presented a number of startling interpretations on the nature of religious visions (Lane, 1983), believed, on the basis of over seventy years of meditation, that the reason Trikuti is so hard to overcome is due to the fact that whatsoever one desires it manifests accordingly. Literally, worlds upon worlds

can be created by sheer thought in the second stage. Thus, the soul can be trapped by an infinite set of cravings, wants, and wishes, which continually attract the mind to ephemeral pleasures (Faqir Chand, 1976). Furthermore, in the grand design of the cosmos, there is a negative force whose sole purpose is to detain the soul from transcending to higher states. This power is known as Kal (time/death), the lord of the mind, in the terminology of the saints in the Sant Mat and Radhasoami traditions (Julian P. Johnson, 1974). Kal is the antithesis of the positive current, Sat, which constantly goes back to the Supreme Lord, Anami Purush. Kal's force is downward (instead of upward) toward the creation. Hence, Kal, though also a manifestation of the Absolute on a lower vibration, represents the main obstacle in the ascent of the soul. The only way a sincere student can conquer Trikuti is by withdrawing the spirit from the mind itself, just as the mind separated from the body. THE THIRD REGION: Daswan Dwar "the tenth door"The refulgence of this region (Daswan Dwar) is twelve times that of Trikuti. Pure pools of ambrosia, called "Mansarovar," abound here. There are innumerable flowers and gardens. Spirits, like beauties, dance at various places. At every place fountains of nectar are overflowing and the streams of nectar are gushing out. How may one describe the splendour and decoration of this region! There are platforms of diamonds, beds of emeralds and plants of jewels, all studded with rubies and precious stones. Bejeweled fish, swimming in pools there, display their beauty and ornamentation, and their glitter and sheen attract attention. Beyond this, there are innumerable palaces of crystals and mirrors, in which spirit entities reside at their respective spots, as allocated by the Lord. The denizens there are spiritual and free from physical taints. Full particulars of these regions are known only to Sants. It is not meet to describe them in greater detail. -- Shiv Dayal Singh, Hidayatnama Certain saints report that there are ten passageways in Trikuti; the first nine are local leading the aspirant only to outlying parts of the second stage. The tenth door, though, opens up into the third region, a dimension beyond mind and matter appropriately entitled Daswan Dwar ("tenth door," so named because of the key passage way in Trikuti).

The third region is exceptionally auspicious, since the student leaves the mind plane altogether and realizes for the first time his/her true Self; as a pure drop of infinite light and love. From Daswan Dwar the pull is inherently upwards; no longer does Kal's negative power attract the free spirit. Like a butterfly liberated from its inhibiting cocoon, the soul flies forth unencumbered to its original and true abode. The lord of this region is known as the "Detached One" and the shabd manifests as a sarangi (stringed instrument) with white light shimmering like diamonds. Daswan Dwar's refulgence is so brilliant that it dims twelve-fold the reddish light of Trikuti. Although the sound current is one constant audible life stream, it has four major gradations: anahad (unstruck); sar (essential); sat (true); and nij (original). For instance, in the third region, the shabd transforms from anahad into sar, which is the movement from the mind to the soul current. Progressively, sar shabd leads into sat shabd, which finally ushers in the nij current of the Supreme Lord, who is absolutely beyond all expression (Bubba [Da] Free John, 1977). One of the central attractions in the third region is Mansarovar, "a vast pool of immortality" wherein the soul is cleansed of residual samskaras (past impressions). Elucidates Sawan Singh (1970): "When the Sikh Gurus built the Golden Temple at what is now the City of Amritsar they surrounded it with a pool of water, to represent on earth the Mansarovar Pool or Lake, of the third Spiritual Region. This pool they called Amritsar, which has the same meaning as Mansarovar--the pool of the Nectar of Immortality. In the same way, the Indian Rishis and Munis (sages and holy men of the past), called the confluence of the Ganges, Jamuna and the now vanished Saraswati, Tribeni, to symbolize on earth the meeting place of the three great streams of refulgent Light in Daswan Dwar. But the real thing that gives liberation lies within and not without." Although Self-realization is achieved in Daswan Dwar, the student has not merged back totally with the Supreme One. Consciousness is identified with the drop/bubble, but not yet with the ocean of love in its awesome entirety. Thus, the soul must evolve even further to achieve full jivan mukti, "liberation while living." The face of the Self has been discovered-- consciousness beyond body and mind is experienced to be the true reality--but the primordial body of the Absolute remains unattained (Sawan Singh. 1974). Perhaps the most frightening phase in the meditator's exploration is through the region known as Maha Sunn (great void) which is located between Daswan Dwar and Bhanwar Gupha. Though the soul is said to contain the light of twelve suns, its brilliance is blinded by the impenetrable darkness which precedes the fourth region. In fact, saints rarely discuss this stage, as it can only be crossed with the help of the inner guru. Outlines Shiv Dayal Singh (1970) of this plane: Having sojourned there (Daswan Dwar) and having enjoyed the glory thereof for a very long time, the spirit of this Faqir proceeded on, in accordance with the instruction of the Guides. After traversing five arab (one thousand million) and seventy five crore yojans upwards, the spirit entity affected ingress into the bounds of Hahoot and witnessed the panorama of that region. There the expanse of ten neel (one thousand million) is enveloped in darkness. Depth of this dark region cannot be fathomed. The spirit went down one kharab yojans, still the bottom was nowhere to be found. Then it (the spirit) turned up and proceeded on the path chalked out by Guru. It was not considered advisable to go down right to the bottom of this region. This region is called Maha-sunn. There are prison cells for the condemned spirits, ejected from the Court of the True Supreme Being. Although these spirits are not subjected to any trouble, and they perform their functions by their own light, yet, as they do not get the darshan of the Lord, they are restless. However, there is a way of their remission also. Whenever Sants happen to pass that way with the spirits reclaimed from the lower regions, some of these spirits fortunately get their Darshan. Such spirits go along with the Sants who very gladly take them to the Court of the Lord and get them pardoned. To cross the abyss without such a guide is impossible according to the masters (Shiv Dayal Singh 1970), because the ascent is not Self-centered but God-centered involving the mauj (will/grace) of the Supreme Lord. In a sense, what we are witnessing is the ultimate surrender. First, the physical body has to be given up (sensory paralysis; out-of-body experience, etc.), then the lower and higher mind (in the stages of Sahas-dal-kanwal and Trikuti), and finally the soul itself (in Sach Khand), which is nothing but a mere bubble in the ocean of Infinity. THE FOURTH REGION: Bhanwar Gupha "whirling cave"The spirit, thereafter, went to Hootal Hoot, which, in Hindi, has been described as Bhanwar-gupha. There is a rotating swing here which all the time in subtle motion, and the spirits ever swing on it. All round, there are innumerable spiritual islands from which the sounds of "Sohang Sohang" and "Anahoo Anahoo" rise all the time. Spirit entities playfully and rapturously enjoy these sounds. Whiffs of scents of various kinds and sweet fragrance of sandal are enjoyed by the spirit there and the melodies of flutes are heard, while it proceeds onwards. [Other characteristics of this region cannot be reduced to writing, as they can be realized by the spirit only when it reaches there after performing Abhyas.] --Shiv Dayal Singh, Hidayatnama Upon arriving in Bhanwar Gupha, the soul's nirat (power to see) and surat (capacity to hear) attain a state of satisfaction (Julian P. Johnson, 1953). This contentment, according to Shiv Dayal Singh's account, is due to perceiving a most intriguing and wondrous structure within the Rukmini tunnel in the entrance to the fourth region. Exactly what this sight is has not been explained by any Radhasoami saint in print. Like all experiences in the upper regions it must be encountered first-hand to be understood, not simply referenced in its decidedly mythological analogies. Bhanwar Gupha is the funnel of the entire creative process from Sach Khand downwards. Its very name exhibits the tremendous power inherent within the region: "whirling vortice". The lord of this realm is termed Sohang ("I Am That"), a descriptive-mantric term which implies a conscious intuition on the part of the soul with its higher identity.

The shabd currents in Bhanwar Gupha are so sweet and enchanting, according to the Saints, that souls live entirely off its invigorating nectar, desiring nothing but darshan of the presiding lord and the manifestations of light and sound. Kabir, the most famous of the medieval saints, describes in his writings (or, at least, those attributed to his pen) how hansas (pure spirits) live on spiritual dweeps (islands) with magnificent palaces for transmundane enjoyment. Faqir Chand, in his Yogic Philosophy of the Saints (1980), gives a more psychological interpretation of the meditator's experiences in the fourth region: "When in the course of meditation man reaches this state of Bhanwar-Gupha he experiences that there was none except his ownself. This centre is compared with Bhanwar which means whirl. At this centre a wheel rotates like a cradle. It means that at this centre a wave springs out of the surat of the meditator and again merges in its own source, or say, it rotates around its own source and produces the sound of Sohang-Flute. The Shabd of this centre is so effective that the meditator enjoys the pleasure of being one with the Supreme Soul." THE FIFTH REGION: Sach Khand "the true realm"On crossing this place, the spirit entity reached the outpost of Sat Lok, where melodious sounds of "Sat Sat" and "Haq Haq" were heard as though coming out of vina (harp). On hearing this, the spirit penetrated further on rapturously. There rose to view the silver and golden streams full of nectar, and vast gardens, each tree thereof is one crore yojans in height, and crores of suns and moons hang from them as flowers and fruits. Innumerable spirits and Hansas sing, chatter, and play on those trees like birds. The wondrous beauty of this region is ineffable. While enjoying it, the spirit entered Though it has been a long time coming, the soul after traversing the lower realms finally reaches its real home, Sach Khand (true region), where even the subtlest duality between the spirit and God are transcended. The Supreme Being, Sat-Chit-Ananda (Truth, Existence, Bliss), is found in Its pure form only in this region, the saints stress. All of the previous planes of existence are but reflections of this infinite abode (Shiv Dayal Singh, 1970). On being admitted to Sat Purush's court, the soul revels in delight, for the inner guru has delivered what he promised: God realization. However, a curious thing happens when the student beholds the Supreme Lord for the first time; the guru is seen as not different from Sat Purush, but rather they are one and inseparable. All along it was not just a human being or an inner spirit guiding the yearning soul but, according to the Saints, the Absolute itself.

Now, at this crucial transformation, the student realizes the Supreme Truth that he/she is also not separate from the divine master or the Lord but in eternal unity with them. This enlightenment, unlike the partial glimpses of insight in the intermediary realms, is permanent and lasting; it is the very root of all manifestations, projections, and creations. One without a second; infinity without measure. Although Sach Khand is the last and final stage, according to the Saints, there are three further levels within it of intensification: alakh (invisible), agam (inaccessible), and anami (nameless). Upon merging with Sat Purush, the spirit is taken up further into the very depths of the Absolute, experiencing what no words or approximations can adequately describe. Shiv Dayal Singh (1970) says it is but "wonder, wonder, wonder; wonder hath assumed a form." Faqir Chand, in this usual iconoclastic manner, describes the highest state as follows: "Beyond Agam is only realization. I do know that there is something in me that listens to the Supreme Shabd. What is that? That I do not know... I used to listen to bells, thunders, and vina, but now I listen only to one sound, which is an unbreakable tune, about which I cannot say any word. It is what it is. Now at this age of ninety-two years I do not care for the Sound and Light too. Why? Because Light is seen by Me (Sat Purush/Anami) and Sound is heard by Me. Then who is great? Light or Sound or He who sees it and listens to it? So far, my realization is concerned, bubble will merge in the ocean. Light will merge in the Light...." (Faqir Chand, 1978) According to the Saints it should be remembered that Sat Purush is not some mysterious God which is vastly greater than our limited selves. Rather, it is, in the most profound sense, our very beings. We are not less than it, nor greater than it. . . we are it. No subject, no object, just pure unqualified Being in an ocean of infinite creative power. It may appear that the Master and God are separate from the disciple, but in truth they are but expressions of the same Whole, the same One (Charan Singh, 1979). SEEDS FOR A FUTURE SCIENCEShabd yoga as an experiential methodology for trans- empirical regions of awarenessThe preceding phenomenological description of the soul's ascent, although undoubtedly fascinating, leaves many problems and unanswered questions, not the least of which concerns the notion of Self realization and God realization. Though we have seen, in a rather armchair fashion, what occurs to consciousness during surat shabd yoga meditations, the ultimate validity of such a process has been left unexamined. For instance, what is considered to be the goal in kundalini yoga (sahasrar chakra) is regarded as but the first stage in shabd yoga. Likewise, jnana yoga (the causal path of knowledge) posits that its method bypasses both kundalini and shabd by directly inquiring into one's conscious existence--the source of awareness itself (Bubba [Da] Free John, 1977). Hence, what we have here is not only a conflict in transpersonal methodologies, but also a paradox over what constitutes ultimate truth and reality. Is shabd yoga higher than kundalini? Does the Advaita Vedanta tradition (jnana yoga) transcend all other spiritual disciplines? The answers, of course, are not easy or forthcoming, except if we happen to belong to a particular school of thought and are consciously or unconsciously prejudiced in our analysis (Lane, 1984). Instead of resorting to quick and premature conclusions, so as to resolve an emotional religious debate, what is needed is a suspension of belief and a program for action that incorporates experientially the various techniques outlined in the contrasting yogic systems. Our purpose here will not be so much to determine which path is higher, but to correlate the findings in an intelligent and comprehensive way. Surat shabd yoga, I suggest, is quite suitable for such a scientific endeavor in that it lends itself to a series of repeatable experiments. With a group of like-minded experimenters, fruitful discussions and inter- subjective dialogues can be based upon direct mystical encounters instead of just imaginative philosophical speculation (Ken Wilber, 1983).

Although many religious advocates claim that mysticism cannot be reduced to science, it should be understood that what goes under the name of spirituality is not exempt from rational inspection. Rather, I would argue, it is not only viable that mystical insights come to the public eye for closer scrutiny, it is necessary. We can no longer turn our backs to the glaring fact that the most important issues in life (the purpose of human beings, life after death, the concept of God, etc.) are often left to the closed systems of dogma and ritual. Genuine science, in the larger context of the term, is naturally amiable to purview any event in human life, if only allowed a reasonable chance. We are, though most of us do not like to admit it, scared of that which we are not sure of. How does the kundalini yogi, or the shabd yogi, or the jnana yogi know he/she has the "highest" path? Regardless of what we may argue or wish to be the case, the bottom line in all religious aspirations is that we do not know absolutely. This ignorance, instead of being something to fear, should be made the very basis of our transpersonal science. Science, in the end, does not provide ultimate knowledge, but presents an ever-widening vision of human life. The necessary seeds for nurturing this larger perspective are more actual experiments in consciousness studies and less juxtapositioning of doctrines. Though we may not want to live in a world void of certainty, reality rejoices in it, with change being the only constant knowable. Hence, surat shabd yoga should be utilized as a practical methodology for transpersonal experiences with the keen understanding beforehand that it will serve as a tool for an open system of investigation; one which accepts the writings of previous masters as useful guidelines but not as unquestionable books of dogma and law (Charan Singh, 1967). Only in this way, can such a yogic discipline be regarded as scientific. It is my contention that the future of transpersonal psychology depends more on the actual transformation of individuals or communities via rigorous spiritual experimentation than the endless theoretical debates between scholars over which path is highest, fastest, and most reliable. Road maps go a long way, no doubt, in helping one find direction, but they do not take a would-be traveler anywhere.

ReferencesChand, Faqir. Science of God Realization. Translated by Swami Yogeshwar. Hoshiarpur: Manavta Mandir, 1978. Chand, Faqir. Jeevan Mutki. Translated by B.R. Kamel. Hoshiarpur: Manavta Mandir, 1976. Chand, Faqir. Yogic Philosophy of the Saints. Translated by B.R. Kamal. Hoshiarpur: Manavta, 1980. Eliade, Mircea. Yoga: Immortality and Freedom. Translated from the French by Willard R. Trask. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1971. Free John, Bubba [Da]. The Paradox of Instruction. San Francisco: Dawn Horse Press, 1977. Johnson, Julian P. Path of the Masters. Beas: Radha Soami Satsang, 1974. Johnson, Julian. With a Great Master in India. Beas: Radha Soami Satsang, 1953. Lane, David. "The Hierarchical Structure of Religious Visions." Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, Vol.15, 1. Lane, David. The Radhasoami Tradition. New York: Garland Publishing, 1992. Lane, David. "Transcendental Sociology". The Laughing Man Magazine, Volume 4, number 4. Moody, Raymond. Life after Life. Atlanta: Mockingbird Books, 1975. Ring, Kenneth. Life at Death. New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, 1980. Sahib, Rai Munshi Ram. With the Three Masters. Beas: Radha Soami, 1974. Rumi. The Teachings of Rumi. Translated & Abridged by E.H. Whinfield. New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1975. Ruhani Satsang, Sawan-Kirpal, and Sant Bani PublicationsSingh, Darshan. Spiritual Awakening (1982) Singh, Kirpal. The Way of the Saints (1976) Singh, Kirpal. Godman: Finding A Spiritual Master (1974) Singh, Kirpal. Heart to Heart Talks, Volume I and II (1976) Singh, Kirpal. The Crown of Life (1973) Radhasoami Satsang Beas PublicationsSingh, Charan Maharaj. Light on Sant Mat (1958) Singh, Charan. Divine Light (1967) Singh, Charan. Quest for Light (1978) Singh, Charan. Die to Live (1979) Singh, Jagat Sardar. Science of the Soul (1972) Singh, Sawan. Discourses on Sant Mat (1970) Singh, Sawan. Spiritual Gems (1974) Singh, Shiv Dayal. Sar Bachan Poetry (Volume One and Two). Translated by S.D. Maheshwari. Agra: Soami Bagh, 1970. Swami Muktananda. Play of Consciousness. Oakland Shree Gurudev Siddha Yoga Ashram, 1974. Wilber, Ken. No boundary. Los Angeles: Zen Center, 1979. Wilber, Ken. Up From Eden. New York: Doubleday, 1981. Wilber, Ken. Eye to Eye. New York: Doubleday, 1983. Addresses for shabd yoga related booksSawan Kirpal Publications | Route 1 Box 24 | Bowling Green, VA 22427 | Mrs. S.D. Maheshwari | Soami Bagh (R.S. Satsang) | Soami Bagh, Agra--5 | INDIA | The Neurobiology of MeditationMeditation is different from rest or sleep. It's a wakeful hypometabolic state with lowered sympathetic activity as opposed to the fight and flight reactions which requires an active sympathetic system. Parasympathetic activity is increased which is important for relaxation and rest. This increase of parasympathetic state is characterized by reduced heart rate, lower systolic blood pressure, lower oxygen metabolism, and an increase of skin resistance. So it's not only a rest state but also physiological relaxation related to to stress relief. But what is the effect of meditation on the brain?During meditation not only general relaxation is experienced but also a reduction of mental activity and positive affect. During meditation the reduced mental activity is mediated by increased activation of networks of internalized attention which trigger the activity in regions that mediate positive emotions. Networks related to external attention and irrelevant processes are decreased in activity. The networks activated for internal attention and positive mood are mainly located in the frontal and subcortical brain regions. The positive affect more specifically increases the activity in the left prefrontal and limbic region of the brain. The internal focused attention is thought to originate in an activation of frontal and thalamic region of the brain. There's also some evidence that experienced meditators show these activations and deactivations in a greater extend compared to novices in the field of meditation. One should keep in mind that these findings relate to meditation in general. Different kinds of meditations can result in slightly different activation and deactivation patterns. Different brain activation networks can thus be activated by different Meditation traditions. These findings mostly result from comparison of small groups of experienced meditators compared to novices. Rubia, K. (2009). The neurobiology of Meditation and its clinical effectiveness in psychiatric disorders Biological Psychology, 82 (1), 1-11 DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.04.003

|