|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Jan Krikke is a former Japan correspondent for various media and former managing editor of Asia 2000 in Hong Kong. He pioneered the study of axonometry, the Chinese equivalent of European linear perspective overlooked by Jean Gebser. He is the author of several books, including Leibniz, Einstein, and China, and the editor of The Spiritual Imperative, a macrohistory based on the Indian Varna system by feminist futurist Larry Taub. Jan Krikke is a former Japan correspondent for various media and former managing editor of Asia 2000 in Hong Kong. He pioneered the study of axonometry, the Chinese equivalent of European linear perspective overlooked by Jean Gebser. He is the author of several books, including Leibniz, Einstein, and China, and the editor of The Spiritual Imperative, a macrohistory based on the Indian Varna system by feminist futurist Larry Taub.

Between Instinct and ConsciousnessEast Asia's "Sophisticated Animism"Jan Krikke

Techno-Animism: How Japan Breathes Life into Machines

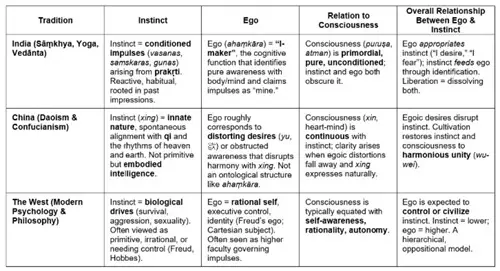

Scholars have often characterized Chinese cosmology as “non-dualist,” “organismic,” or “processual.” These terms hint at a worldview in which nature, mind, and cosmos comprise a seamless whole. Yet one description captures the heart of this worldview more directly: the Chinese conception of the Dao can be understood as a sophisticated form of animism. Not animism in the old anthropological sense of “primitive spirit-belief,” but in the sense deployed in recent scholarship by the likes of Graham Harvey, Tim Ingold, and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro. It means a relational ontology in which the world itself is alive, responsive, and participatory. Framed this way, Chinese thought dissolves the Western split between instinct and consciousness, offering a unified vision of how living beings engage the world. In classical Daoism and Confucianism, nature is not inert matter governed by external laws but a self-organizing field of qi. This vital, dynamic energy forms, dissolves, and transforms all phenomena. Mountains rise, rivers flow, clouds swirl, and animals migrate because they participate in emergent patterns of the Dao, not because they are mechanically pushed from behind. These patterns have tendencies shi, rhythms du, and dispositions li that arise “organically” from within the cosmos. Scholars like Joseph Needham, Roger Ames, and David Hall argued that classical Chinese thought is best understood as “organismic,” or as a world of interpenetrating processes rather than discrete entities. Within this worldview, instinct (xing) refers not to an animalistic residue but to an organism's innate nature—the spontaneous pattern by which it participates in the “rhythms of heaven and earth.” A seed germinating, a bird navigating, and a person experiencing compassion are all expressions of xing. Instinct is consequently a form of embodied intelligence and not something to be overcome. Consciousness (xin, “heart-mind”) is not a separate rational faculty but rather the refined awareness that harmonizes with xing: when consciousness is unobstructed, instinct and awareness combine in wu-wei (“effortless action”), allowing for spontaneous yet appropriate responsiveness to the world. Chinese cosmology resembles what anthropologists nowadays refer to as new animism: a way of thinking in which personhood, agency, and responsiveness are emergent relational properties rather than intrinsic biological ones. The cosmos is a living web, and humans, animals, tools, and environments all participate in its dynamic coherence. India provides an enlightening contrast. Indian philosophy, as a rule, views consciousness as primordial and instinct as the result of conditioning. In Sāṃkhya, for instance, the distinction between puruṣa (pure consciousness) and prakṛti (the material and psychological processes, including instinct) frames the entire metaphysics.

In Advaita Vedanta, atman, pure awareness, becomes entangled in ahaṃkāra,, or the ego-construct, thereby creating instinctual habits, called vasanas or samskaras. Here, instinct is something to see through, not integrate. The contrast reinforces the broader triad: in the West, consciousness rises above instinct; in India, consciousness precedes instinct, whereas in China, instinct is consciousness in its somatic mode. ShintoJapan provides a second East Asian example of “sophisticated animism,” though with a distinct emotional tone. In Shinto, the world is inhabited by kami—not gods, but presences, forces, or qualities dwelling in natural forms, places, and even crafted objects. According to East Asian scholar Thomas Kasulis, Shinto perceives the world as a web of “relationships of presence” rather than separate entities. The boundary between living and non-living is porous: tools, utensils, musical instruments, and even machines can acquire ki (Japan's equivalent of China's qi), a palpable vitality. Tsukumogami, the idea that old or well-used tools gain spirit, suggests that objects accumulate a biography and moral weight. This worldview shapes Japan's cultural relationship to machines and robots. Where Western culture is haunted by Frankensteinian anxiety-machines rebelling against their creators-Japan typically views robots as companions, collaborators, or social actors. To be sure, this does not mean that all Japanese engineers personally hold animistic beliefs. Many roboticists work from a secular engineering mindset, and Shinto blessings of robots, which do occur, especially in small and mid-sized firms, are often ceremonial rather than metaphysically literal. Buddhist temples using robots, such as the Mindar android at Kodaiji, remain the exception. Similarly, contemporary Chinese urban attitudes toward technology derive more from state-driven materialism and rapid industrialization than from explicit Daoist cosmology. Traditional worldviews coexist with modern secular pragmatism, and neither is best thought of as monolithic or universally operative. Still, the deeper cultural ontology matters. In Japan, technology is not alien or threatening but continuous with life. Machines can be friendly, expressive, and socially integrable; they can be welcomed into eldercare homes or even religious spaces. The influential paper on techno-animism by Jensen and Blok argues that Japan's robotics culture arises from the fusion of industrial modernity with enduring animistic sensibilities. New participantsChina shares something of this disposition, albeit in a more cosmological register. Insofar as qi permeates both nature and technology alike, machines can be seen to extend natural processes. Chinese mechanical inventions, from Zhang Heng's seismoscope to the clock tower of Su Song, were designed to harmonize rather than dominate cosmic order. Chinese attitudes toward AI today often blend strong pragmatism with a sense that the technology will be woven into the existing relational patterns of society and the cosmos. Taken together, the Chinese Dao, the Japanese kami-world, and its modern technological expressions all suggest that sophisticated animism represents a continuingly powerful interpretive lens for East Asia: it explains why instinct and consciousness are not opposed but intertwined, and why in East Asia robots are so often greeted not with anxiety but rather curiosity, affection, or even reverence. If the world is conceived as a living field of dynamic forces, then machines become simply new participants in an already-living cosmos. Technology is not an invader but a collaborator. The “spirit in the machine” is not superstition but the extension of a worldview in which everything is interrelated and participates in the larger whole. Further reading:Kasulis, Shinto: The Way Home (on kami and tools) Ames & Hall, Thinking Through Confucius or Dao De Jing: A Philosophical Translation (on xing and organismic process) Allison, Millennial Monsters or Schodt, Inside the Robot Kingdom (early work on Japanese robotics culture) Jensen & Blok, Techno-Animism in Japan (2013 paper with a similar thesis)

|